Picture: Getty/Michael Putland

Tony McPhee was 14 when he got a guitar for Christmas in 1958. Raised on his siblings’ rock’n’roll and blues records, the Streatham axe-prodigy played his first gig a year later, at his school’s Christmas concert.

Leaving school at 16 in 1960, McPhee started work as a GPO engineer. After witnessing Cyril Davies & The All-Stars play the Marquee, he formed blues-based outfit the Groundhogs, named after a track on John Lee Hooker’s 1959 Chess album House Of The Blues. Thanks to McPhee’s knowledge of obscure blues material, they became a fixture on the UK circuit, eventually backing the likes of Hooker, Little Walter and Jimmy Reed on tours and album sessions, and dubbed, by Hooker, as “the [UK’s] number one blues group”.

By 1966, with promoters favouring soul bands, the original Groundhogs disbanded. Yet, witnessing the start of a second blues resurgence, McPhee re-formed the group in 1968. With Pete Cruickshank on bass, and Ken Pustelnik on drums, they signed to UA offshoot Liberty. By the time of 1969’s Blues Obituary, McPhee had absorbed the influence of Jimi Hendrix, acknowledged the death of 12-bar blues “authenticity” and embraced the power of amplification and studio production. With 1970’s Thank Christ For The Bomb and 1971’s Split, McPhee created two multitracked, effects-laden, conceptual blues-rooted masterpieces. Supercharged, fractured and raging, the albums became McPhee’s albatross; how to improve on them, where to go next.

After the group split in 1976, McPhee formed back-to-basics R&B band Terraplane, and later the Tony McPhee Band. Since then, he’s been name-checked by everyone from Julian Cope and Mark E. Smith to Karl Hyde, Stephen Malkmus and the Arctic Monkeys. In tribute to McPhee, who sadly passed away following a series of strokes, MOJO takes a dive into his singular back catalogue.

10.

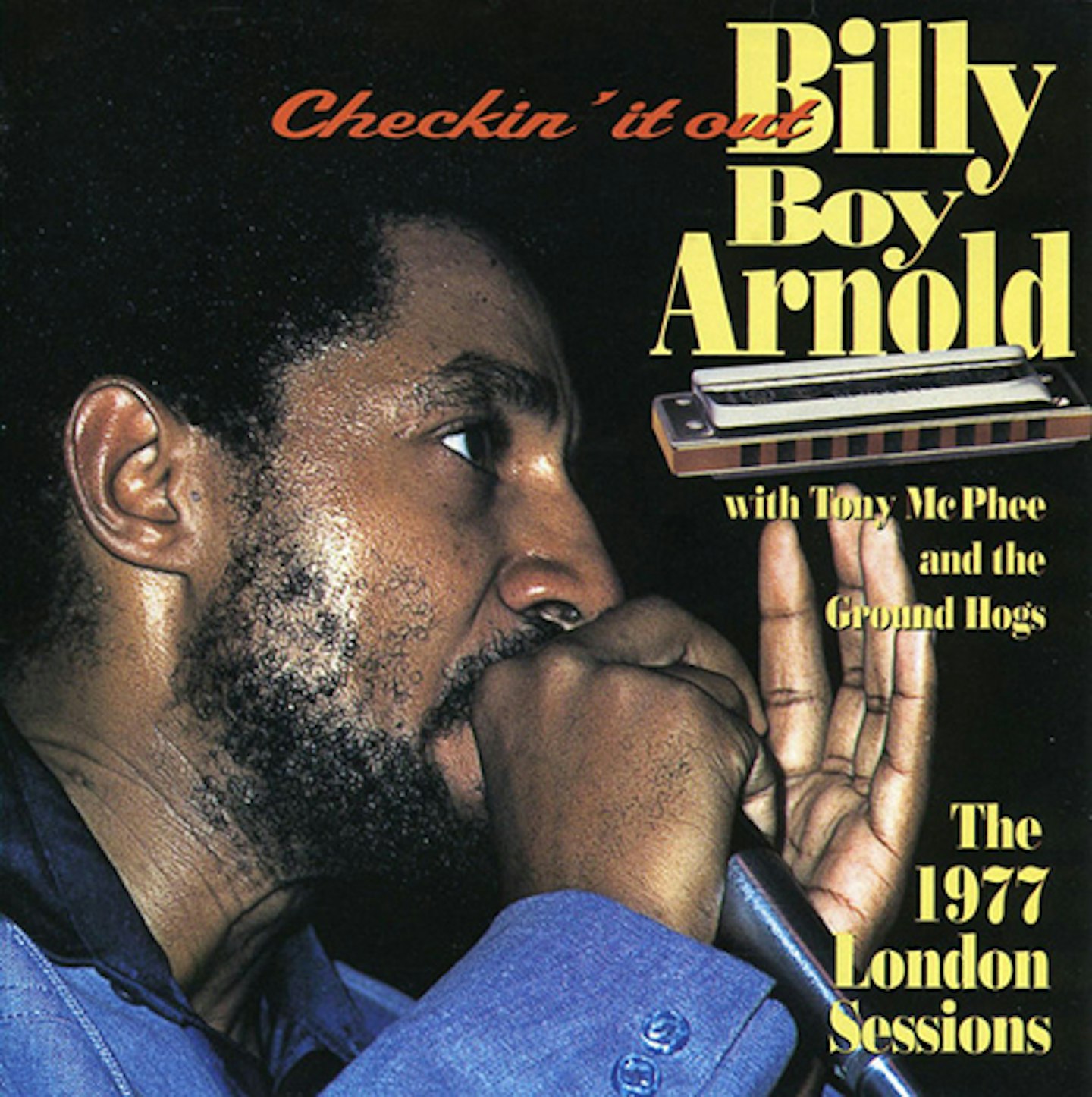

Billy Boy Arnold With Tony McPhee And The Groundhogs

Checkin’ It Out

SEQUEL, 1996

The Groundhogs were a hugely admired band behind many US and UK blues artists in the ’60s and ’70s. For example, Andy Fernbach’s If You Miss Your Connexion (Liberty, 1969) features psychedelic blues-rock by a little-known Bournemouth guitarist, produced by McPhee using the Groundhogs’ Pustelnik/Cruickshank rhythm section. Here, however McPhee’s post-Groundhogs Terraplane play with the 42-year-old Chicago harmonica virtuoso on a 1977 European tour. It’s a powerhouse, louche and electric R&B party, as mush-mouthed opener Dirty Mother Fucker makes clear.

9.

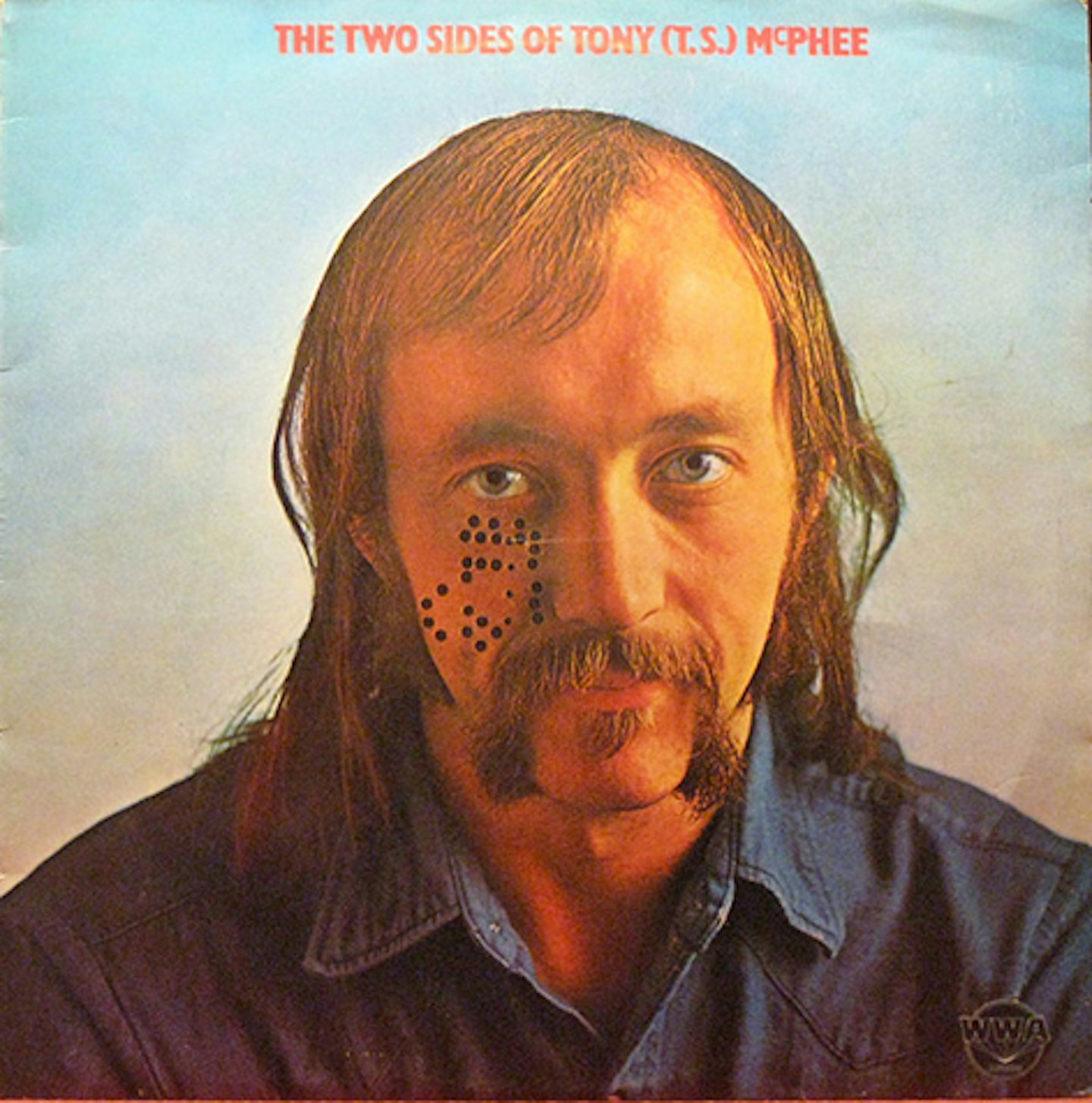

T.S. McPhee

The Two Sides Of T.S. (Tony) McPhee

WWA, 1973

Recorded in his home studio and promoted with a one-man synthesizer tour, The Two Sides… might be McPhee’s most peculiar record. On side one, five solo-guitar country blues; on the flip, something else entirely. Inspired by Edgar Winter’s use of an Arp 2600 synth, McPhee invested in two and, with a Rhythm Ace drum synthesizer and electric piano, wrote a 20-minute electronic suite about the evils of fox hunting. Using synths to emulate baying hounds, tolling bells, hunting horns and the tortured fox, McPhee veers from poetic narration to angry proto-punk vocals as twin ARPs create a burbling atmosphere of sci-fi folk-horror throughout.

8.

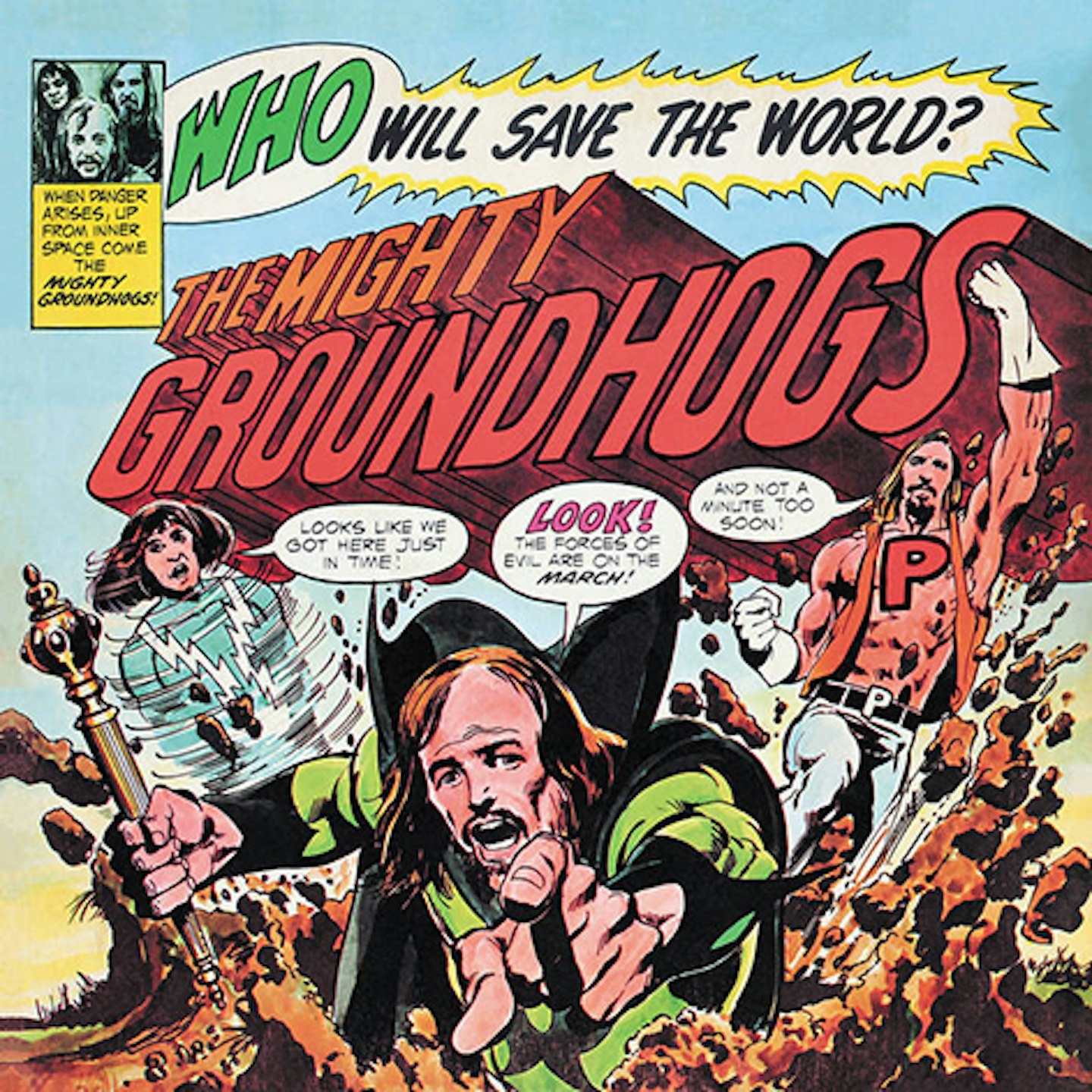

Groundhogs

Who Will Save The World? The Mighty Groundhogs

UNITED ARTISTS, 1972

Exhausted from touring, “stuck in the quagmire of Split”, convinced that promoters and the music press had it in for them, and critical of his fellow band members, McPhee entered the new, sterile De Lane Lea studios in Wembley hoping to make the new Groundhogs album, “more melodic, more dynamic”. Inspired by Marvel artist Neal Adams’ cover art which depicted the group as superheroes fighting pollution, over-population and war, McPhee brought in keyboards, mellotron and oily, multitracked guitars for a dark, disorientating sci-fi journey through a cyanide-poisoned Earth that’s “just a cage seven thousand miles wide!”

7.

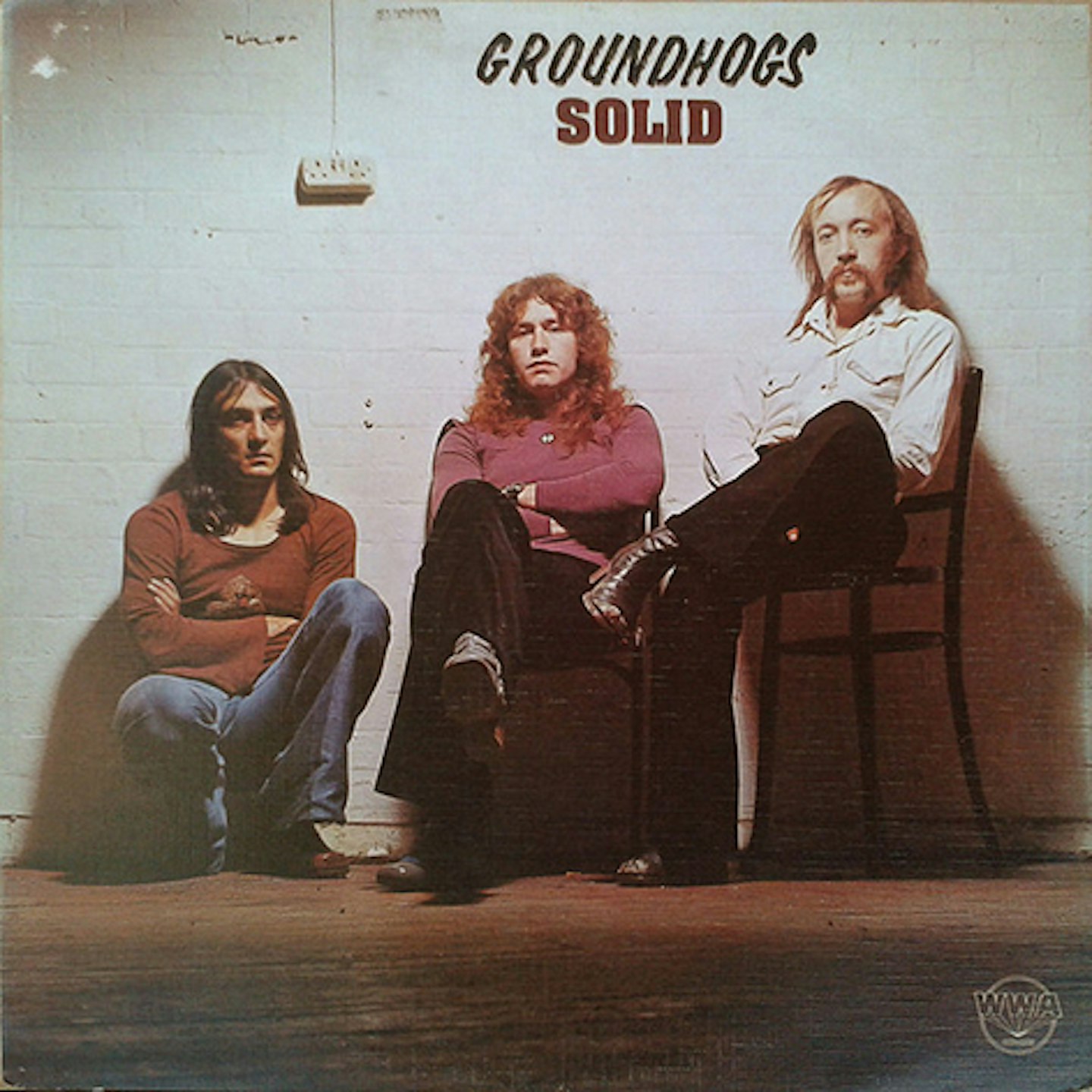

Groundhogs

Solid

WWA/VERTIGO, 1974

As suggested by its perfunctory, artless cover image – McPhee, Cruickshank and drummer Clive Brooks, who had replaced Ken Pustelnik two years earlier, gloomily stare – Solid is a cold, sterile, angular work, at times closer to post-punk than prog-blues. Right from the sickly, phased, multitracked guitars and brute-rhythm section of the album’s opening track Light My Light (lyrics about death, decay and a darkened Earth) we are in a fug of existential and environmental despair. Riffs stab, keyboards jab, vocals bite and the LP is drenched in a trebly metallic sweat of high anxiety and fear. Managing to alienate band, record company and management, it arguably signalled the end of the group as a true creative force.

6.

Groundhogs

BBC Live In Concert

STRANGE FRUIT 2002

“Our music is often so basic people miss the point,” said McPhee. “On live gigs we’re never the same twice – one night they might think it’s Captain Beefheart up there and the next Muddy Waters. It should be a spontaneous reflection of the musicians’ emotions on the night.” Such statements were often McPhee’s way of defending the fact that the Groundhogs could be an erratic live band who struggled to replicate their studio-augmented power on-stage. Taken from three outside broadcasts between 1972 and 1974, this is almost certainly their finest live document, containing the best-ever live renditions of Split Pt.1 and Cherry Red.

5.

Groundhogs

Blues Obituary

LIBERTY, 1969

The second blues boom in Britain was short-lived, and in order to keep the Groundhogs working McPhee decided to transform the blueprint. To follow-up their Mike Batt-produced debut, Blues Obituary was recorded in June 1969 at Marquee Studios in London with Gery Collins and Colin Caldwell engineering, the rote 12-bar sound transformed into something hypnotic, underground, supercharged. McPhee’s guitar is a thing of descending drones and howling shamanic dread, his vocals of paranoia and disaffection made eerie by his ability to bend words like notes, à la Son House. In case the message was unclear, the cover, shot in Highgate cemetery, left no one in doubt.

4.

Groundhogs

Crosscut Saw

UNITED ARTISTS, 1976

Originally intended as a Tony McPhee solo long-player before management encouraged the guitarist to release it under the Groundhogs name, this low-slung affair of slow, loping menace finds McPhee’s guitar corrupted and perverted by the EMS Synthi Hi-FLi guitar effects unit, his mind turned bitter by divorce. Visceral lyrics of paranoia and recrimination are spat out over epic space-blues dirges that shift jarringly into analogue storms of sci-fi disturbance and frenzied metallic trauma. Vastly underrated, and deeply unsettling, it’s an album that ultimately feels closer to schizoid Sabotage-era Black Sabbath than the Groundhogs of two years earlier.

3.

Groundhogs

Hogwash

UNITED ARTISTS, 1972

Hogwash was both the last truly great Groundhogs long-player, and their first following the departure of drummer Ken Pustelnik. Band camaraderie had gone, and so had some of their rhythmic cohesion and artistic direction. Following the critical and artistic failure of Who Will Save The World?, McPhee went back in the direction of Split’s anxiety, turmoil and power. The new trio lost themselves in modulated vocals, alien harmonics, and menacing electronic distortion by way of ring oscillators, ARP synthesizers and mellotrons. New drummer, Egg’s Clive Brooks, played it safe, allowing McPhee and Cruickshank to lock themselves into a battle of infernal horsepower riffs and jet plane amplification.

2.

Groundhogs

Thank Christ For The Bomb

LIBERTY, 1970

Manager Roy Fisher devised the title, hoping for some post-Lennon controversy by coupling “Christ” with the nuclear apocalypse. Initially thinking it was a terrible idea, McPhee ran with Fisher’s PR stunt. Hammering around “chords and notes that shouldn’t fit”, and reusing riffs from his old psych-pop group Herbal Mixture, McPhee made a supercharged power-trio concept album, a crunching mix of Sabbath, Beefheart, and the trio’s brand of harmonic heaviosity, as side one ruminates on two World Wars and the bomb culture generation, and side two tells of a Chelsea gentleman who returns to nature, “my food from bins, my water from ponds”.

1.

Groundhogs

Split

LIBERTY, 1971

The first ‘side’ of Split was written by McPhee following “a mental ‘aberration’… a ‘panic attack’ that lasted a few months”. In four parts and lasting 20 minutes, it’s an instrumental and lyrical expression of schizophrenia, a frantic scouring storm of discordant sustain, fuzz and wah wah guitar patterns, thunderous drumming, earthquake bass, and addictive riffs incorporating ideas of split personalities, loneliness, and Yogic mind and body separation. With a second side that features the scorching, pummelling euphoria of Cherry Red, the psychedelic Black Sabbath dirge A Year In The Life, and Groundhog, McPhee’s rearrangement of Ground Hog Blues, the John Lee Hooker song that gave the band its name, the album became an immediate best seller, reaching Number 5 in the UK on the back of sales boosted by a support tour with The Rolling Stones.