WHEN DID PEOPLE learn to hate The Doors? In the 1979 issue of The Rolling Stone Record Guide, arguably the first How To Buy LP guide, the recorded works of Jim Morrison, Robby Krieger, John Densmore and Ray Manzarek were accorded an array of fairly-proportioned star-ratings, ranging from two to five, with the critic responsible, Billy Altman, describing the group as “brash, courageous, intelligent, adventurous, uncompromising and unique.” Then, for the “revised” 1983 edition something happened and the book’s editor, Dave Marsh, stepped in, dismissing the group as “banal…adolescent… and pompous…”. While it was not uncommon for this San Francisco-based publication to take against LA groups, this felt like a significant shift. Although a possible kickback against Danny Sugarman and Jerry Hopkins’ sensationalist 1980 biography No One Here Gets Out Alive, the now upwardly mobile magazine was also severing ties with an emblematic band of the ’60s counterculture who it now deemed indulgent, wrong-headed, boorish and pretentious. Of course, throughout their five-year career, from their brooding 1967 debut to the thug-growl motorik blues of 1971’s L.A. Woman, The Doors became all these things. Also, there is perhaps no other US rock frontman whose demise was, in certain eyes, more pathetic; a once-beautiful hybrid of Narcissus, Dionysus and Marsyas brought low by his own arrogance, vanity and excess, Morrison became an embarrassing figurehead for the death of the ’60s: disown him at all costs.

“Iggy Pop and Patti Smith have both cited the importance of The Doors.”

Unfortunately, Oliver Stone’s well-intentioned attempt to resurrect the band with his 1991 biopic only served to make things worse, underlining the moral excesses and stylistic clichés of Morrison and co, while adding some high-blown untruths of the director’s own for good measure. In short, on Stone’s watch, The Doors became an indulgent cartoon of psychedelic profundity even easier to hate than the ’60s original. To say you hated The Doors in the ’90s sometimes meant little more than you hated that scene where Val Kilmer, Kyle MacLachlan and Kevin Dillon pretend to write Light My Fire.

Yet, in recent years, a backlash against the backlash has been underway. Iggy Pop and Patti Smith have both cited the importance of The Doors’ booze-sodden anti-cute late-’60s performances as massively influential on the coming wave of punk, while surviving band members John Densmore and Robby Krieger have re-assessed their band with something approaching critical distance. Similarly, the 50th anniversary LP reissues and Bright Midnight series of live recordings have both introduced new fans to the full, wild creative spectrum of the group.

As such, the purpose of this rundown of the essential Doors records has been to reassess this much-maligned group freed from past prejudices in the context of present-day enlightenment. Break on through to the other side, as someone once wrote.

10.

The Best Of The Doors

ELEKTRA, 1985

To quote the deathless 1991 Kids In The Hall Doors-fan sketch, “Greatest Hits albums are for housewives and little girls!”, and surely the most tedious opinion on The Doors is that they were a great singles band and nothing more. But in that barbed, supposed put-down lies a great truth, that The Doors were one of the greatest singles bands of the 1960s and that listening to a good best of (ideally this expertly-sequenced 1985 double) remains a thrilling and revelatory experience. Alternatively, check out this writer’s Spotify compilation, The Soft Pop Parade, which reimagines The Doors as a cheeky little ’60s pop group who only ever recorded the one LP.

You say: “Buying The Doors is easy: L.A. Woman plus any cheap greatest hits compilation. The rest is disposable.” Ian Burdon @Cosmic_Serf, via Twitter

9.

In Concert

ELEKTRA, 1991

Taking performances recorded from 1968-70 in LA, New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Detroit and Copenhagen – previously featured on such live releases as 1970’s Absolutely Live, 1983’s _Alive, She Cried_and 1987’s Live At The Hollywood Bowl – utilising something in the region of 2000 edits by producer Paul Rothchild, and edited together as one long concert, this 3-LP/2-CD set is a true Frankenstein’s monster, both in conception and its terrible brilliance. Perfectly capturing Morrison’s self-loathing in the face of grand adoration (Morrison: “Shut up!” Audience: “We love you!”), and the band’s precarious tightrope walk between danger and chaos, it also showcases how great Manzarek, Krieger and Densmore were as a live improv trio.

You say: “A real humdinger that LP. My favourite Doors live set.” Ian Fraser Johnston @IanFJohnston, via Twitter

8.

Live In Detroit

BRIGHT MIDNIGHT, 2000

Recorded at the Cobo Arena in Detroit on May 8, 1970, during the band’s 1970 Roadhouse Blues Tour, 2-CDs capture the full spectrum of the live 1970 Doors experience, from tight powerhouse rock to rowdy bar band anarchy and freeform improv-blues noise. Mixed and mastered by Bruce Botnick for 1970’s Absolutely Live, and with The Lovin’ Spoonful helping out on guitar and harmonica, it’s also one of the best sounding concert albums from that era. Morrison is funny, charming, boorish and magnetic, the band supremely tight and, give or take a few plodding blues covers, the curfew-breaking two-hour-plus running time (which got them banned from the venue) invests the show with an epic, wired power.

You say: “That Motor City energy makes it a performance for the ages.” James B @supershineon, via Twitter

7.

The Soft Parade

ELEKTRA, 1969

The Doors’ most misunderstood and critically slated LP is also the one that has aged most interestingly. With Morrison’s drinking now severely hampering his creativity, Krieger stepped to the fore as songwriter with Rothchild using Morrison’s sozzled paranoid croon as just another instrument alongside Paul Harris’s string arrangements and Curtis Amy’s jazz sax. Beyond the Sinatra-meets-Stooges wildness of Touch Me, the result is a sort of art-rock concept album. Tracks like the despairing Wishful Sinful, self-parodic Shaman’s Blues and the jazz-meets-Dylan nightmare of Runnin’ Blue are sites of creative chaos centred around Morrison’s own mental and creative collapse.

You say: “A key LP in understanding The Doors. It shows the impact Rothchild had in shaping their sound.” Ana Leorne @analeorne, via Twitter

6.

An American Prayer

ELEKTRA, 1978

Seven years after Morrison’s death, and in the wake of two Doors LPs Manzarek, Krieger and Densmore had recorded without the singer, the three surviving Doors reconvened to record their ninth and final LP with their frontman. Utilising spoken-word and a cappella recordings from 1969 that Morrison had intended for an LP with composer Lalo Schifrin, the trio produced a brilliantly surreal jazz-rock album that is by turns haunting, comic, and nightmarish. Eulogised by Patti Smith in Creem as “treasure unearthed…”, An American Prayer is an apocalyptic road movie, Morrison sounding like a stoned West Coast Colonel Kurtz, uncertain whether to “plan a murder or start a religion.”

You say: “Way better than any cobbled-together posthumous LP has any right to be.” @BobbyLeeBoogie, via Twitter

5.

Waiting for The Sun

ELEKTRA, 1968

With no more songs left over from their touring roster, the band found themselves in LA’s TTG Studios with a new 16-track deck, scouring Morrison’s old notebooks for scraps that could be turned into radio hits. As a perfectionist, Paul Rothchild demanded take after take, yet with new drinking buddy Bobby Neuwirth in tow, Morrison was a drunken liability. The end result is a cracked mix of dream-light radio pop (Hello, I Love You; Wintertime Love), goth-militarism (The Unknown Soldier; Five To One) and meandering experiments in genre and tone (Spanish Caravan; Yes, The River Knows).

You say: “Fave rollicking pop single (Hello, I Love You), fave demonic rabble-rouser (Five To One), and they invent The Divine Comedy (Wintertime Love).” @HeyKidsShop, via Twitter

4.

Morrison Hotel

ELEKTRA, 1970

“The future’s uncertain and the end is always near. Let it roll, baby, roll.” Recorded while an ailing, self-loathing Morrison was getting drunk every night at the Whisky A Go Go, Morrison Hotel is the sound of exploitation and resurrection, the band feeding off their singer’s nihilism to recapture their own dark beauty. Simultaneously optimistic and fatalistic, part-inspired by the sinister country-gospel of the Stones’ Let It Bleed, and partly a response to the expensive, protracted sessions for The Soft Parade, Morrison Hotel possesses a menacing blues minimalism; Morrison’s lyrics touching on serial killers (Land Ho!), pollution (Ship Of Fools) and the Vietnam War (Peace Frog), but also innocent love declarations (Blue Sunday; Indian Summer).

You say: “Morrison and the band give us a bluesy, earthy, stripped-back take on their affairs.” DC Kneath, via email

3.

L.A. Woman

ELEKTRA, 1971

Recorded in the wake of Janis and Jimi’s deaths and Morrison’s own controversial conviction for indecent exposure, L.A. Woman is an LP overshadowed by ill omens. Disowned by producer Paul Rothchild, who believed their new songs “sucked”, the group jammed with engineer Bruce Botnick in the band’s LA offices, Jim singing in the bathroom, Jerry Scheff’s bass and Marc Benno’s rhythm guitar adding a curious, paranoid warmth to the new Doors blues sound. Centred around noirjazz epic Riders On The Storm and the West Coast motorik of the title track, it’s an LP of rowdy melancholy introspection where forlorn psychedelic pop (Love Her Madly; Hyacinth House) punctuates shapeshifting funk-blues (The Changeling; The WASP).

You say: “A 40-minute, Chandler-like takedown of LA’s phoney ascendancy.” @ST_Television, via Twitter

2.

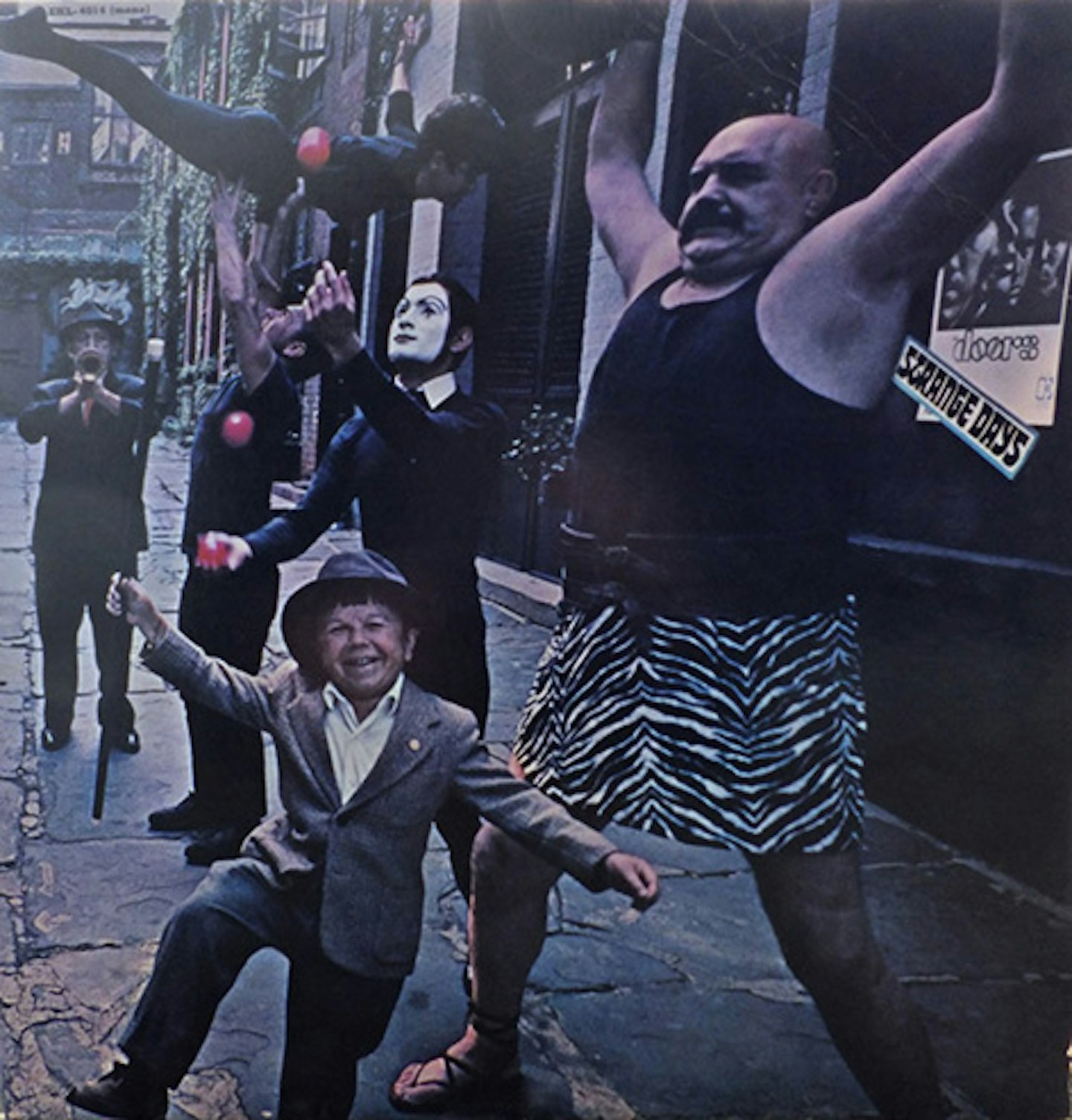

Strange Days

ELEKTRA, 1967

Recorded on 8-track at Sunset Sound Studios, fast on the heels of their debut, and often with a heavily stoned Morrison, Strange Days could have been a disaster. Instead, it is their warped masterpiece. “We expanded song form by using plot, spoken voice and sound effects,” said Morrison, and with the exception of Chicago blues single Love Me Two Times, Strange Days is the sound of The Doors turned weird, haunted, uncanny. Manzarek adds marimba and synthesizer, Clear Light’s Doug Lubahn brings in a necessary bass undertow, and Krieger’s guitar unsettles, not least with that baying hound slide on Moonlight Drive. Moods shift, tempos change, and Morrison tunes into the coming turmoil of 1968, and his own paranoia.

You say: “Strange Days was the first Doors album I heard and it’s still my favourite.” @c21stprimitive, via Twitter

1.

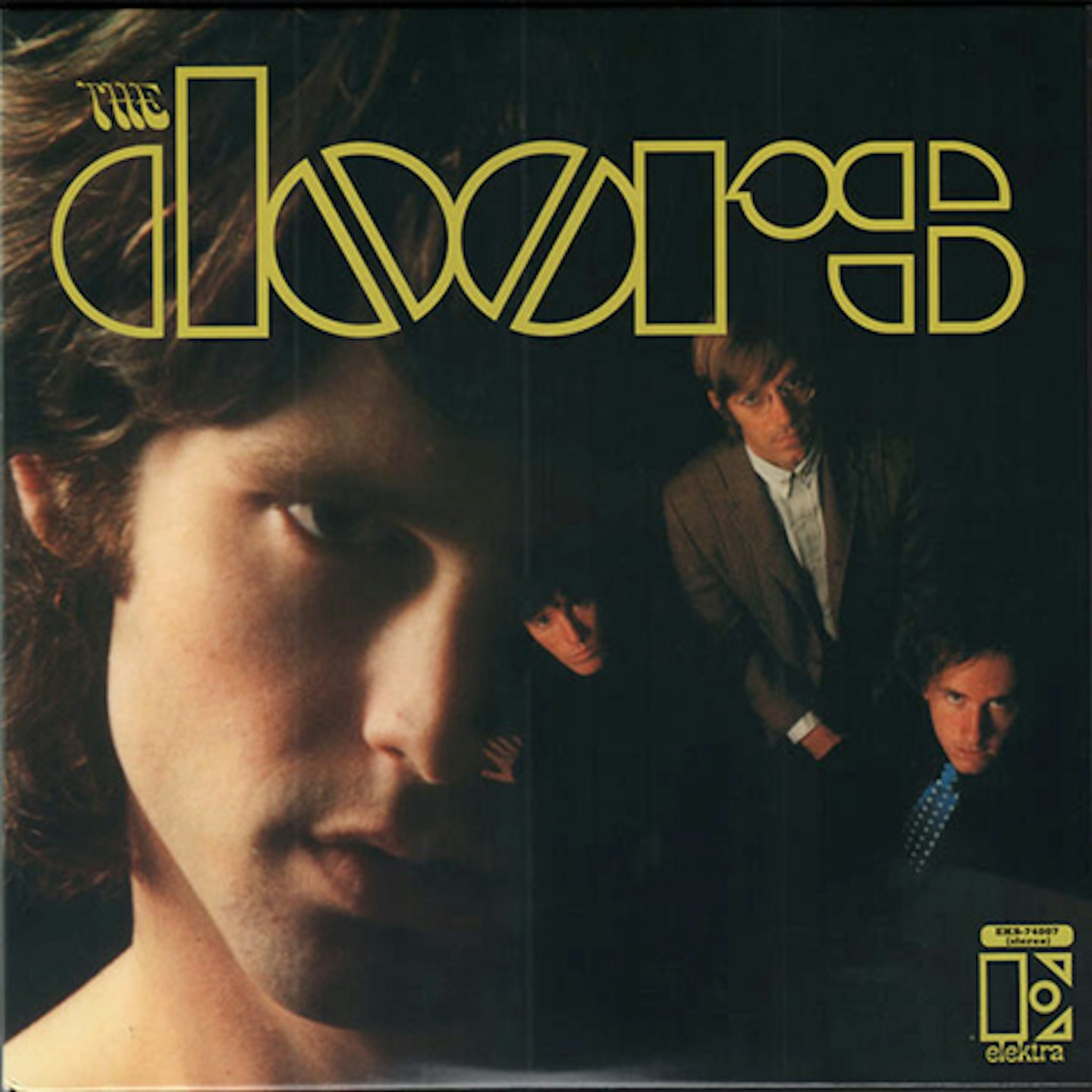

The Doors

ELEKTRA, 1967

At this stage, they were still Ray Manzarek’s band. The one with the practice space and the UCLA film-school vision, Manzarek regarded The Doors as the first cinematic rock group, and with producer Paul Rothchild and engineer Bruce Botnick retaining the meshed electric thrill of the group’s Sunset Strip live sessions, The Doors is both movie and soundtrack. Manzarek, Krieger and Densmore’s electric jazz trio support Morrison’s seductively sinister leadingman croon through a dream setlist of pulsating LSD bossa (Break On Through…), twilight funk (Soul Kitchen), Blakean lullabies (The Crystal Ship), blues-rock sleaze (Twentieth Century Fox; Back Door Man), bright summer pop (I Looked At You; Take It As It Comes) and two straight-up masterpieces: Vox Continental baroque pop epic Light My Fire and the Oedipal apocalypse of The End, which summons the ’60s’ death-rattle three years ahead of Manson.

You say: “Debutante darkness, big hit single, sets out their stall perfectly.” @rustedrail, via Twitter

NOW DIG THIS

Although the two LPs that Manzarek, Densmore and Krieger recorded after Morrison’s death have come in for their fair share of opprobrium, they’re not as bad as the naysayers make out. If 1972’s Full Circle had been released under another band name, it would now be revered as a lost classic of early-’70s jazzrock. Of the numerous Doors biographies and autobiographies available, highlights include Densmore’s Riders On The Storm, Robby Krieger’s Set The Night On Fire, James Riordan’s Break On Through, and 2021’s The Collected Works Of Jim Morrison. Film-wise, Tom DiCillo’s When You’re Strange is the best Doors documentary, despite some curious stylistic choices, and someone still needs to release a remastered version of Morrison’s 1969 art-movie HWY, An American Pastoral.