Formed in Toronto, Canada in 1968 and active until 2015, Rush began as Led Zeppelin wannabes and ended up being the geeks who inherited the earth. Their long road to critical and cultural rehabilitation took in grandiose prog and UK new-wave influences, Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson and Neil Peart wearing their virtuosity increasingly lightly until 2012’s chops-laden last hurrah, Clockwork Angels.

Banger Films’ intimate 2010 profile Rush: Beyond The Lighted Stage was an important milestone that further-widened their audience. Capturing the loveable, beating-heart of Rush and their enduring three-way bromance, its rich archive footage - and a memorable scene in which Lee, Lifeson and Peart share an increasingly drunken dinner - underlined what fans already knew: this was a goofball group of astonishing talents; a band who sounded and interacted like no other.

Famously self-sufficient - “It was hard to believe only three guys were making all that sound”, Thin Lizzy’s Brian Roberston once told this writer - Rush were unusual amongst bands who’d began as hard-rock acts. Like David Bowie, say, their sound was always shape-shifting, and unlike, Aerosmith, say, they quickly abandoned the more hackneyed terrain of hard-rock lyrics to explore philosophy, ethics and the human condition. Sure, Caress Of Steel’s 1975 song I Think I’m Going Bald was fun, but antidote to all drummer jokes Neil Peart would grow to become a highly-acute wordsmith, hence 1993’s Cold Fire, a brilliant portrayal of a relationship in trouble.

There was no happy ending. Geddy Lee’s 2023 memoir My Effin’ Life revealed that, prior to Peart’s heartbreaking passing to brain cancer in January 2020, he and Lifeson had kept the drummer’s illness a secret for three years, as per his wishes. Earlier, Rush had bowed-out with 2015’s final, acclaimed US tour R40, which celebrated Peart’s 40 years in the band. The R40 set cherry-picked songs from Rush’s 19 studio albums in reverse chronological order. Rather than do that, MOJO's chief Rush-nerd James McNair has ranked every Rush album order of greatness, from the worst to best...

19.

Test For Echo

(ATLANTIC, 1996)

“We were a bit burnt creatively” Geddy Lee conceded. While Test For Echo was as virtuosic as ever, its title track made for a dirgy, rather pedestrian opener and much of the album sounds like a gallimaufry of off-cuts. Even Peart’s lyrics seemed less honed, Dog Years’ talk of canines “chasing cars in doggy heaven” lacking his usual pedigree. The run-up to Test saw Lifeson make solo LP _Victor_and Peart release a Buddy Rich tribute album while Lee spent time with his infant daughter. When Rush reconvened, inspiration levels were low, indulgences such as Driven’s three bass-guitar tracks indicative of a rare wobble.

18.

Vapor Trails

(ATLANTIC, 2002)

Having lost his daughter Selena in a car crash and his first wife Jacqueline to cancer, Vapor Trails was an Olympian feat of courage for Rush’s drummer, who had to regain equilibrium after years without playing. “Pack up all those phantoms / Shoulder that invisible load”, ran Peart’s lyric for Ghost Rider, referencing the epic motorcycle journey he’d undertaken while grieving. Pointedly, there are no synths on Trails, a stark, ultimately positive LP which accrued hard miles to get back. Its jarring, overly-compressed sound fell foul of the loudness wars, but was somewhat spruced up by a 2013 remix.

17.

Snakes & Arrows

(ATLANTIC, 2007)

After the creative palette cleanser that was 2004 rock covers EP Feedback, Lee, Lifeson and Peart’s penultimate studio release was the first of two with avowed Rush nut and sometime Foo Fighters producer, Nick Raskulinecz. Though the LP’s three instrumentals are decent, YYZ or La Villa Strangiato they ain’t. Replete with some of the distinctive chord voicings Lifeson used so memorably on 1978’s Hemispheres, opener Far Cry impresses, while harmonically-daring deep cut Bravest Face is a Rush song like no other. A decent if somewhat obtuse LP, Lee & Lifeson’s jam-sessions still audible beneath the songs.

16.

Hold Your Fire

(MERCURY, 1987)

Home to fellow Canuck Aimee Mann’s guest vocal on poignant classic Time Stand Still, Hold Your Fire was something of a last hurrah for Rush’s more keyboard-heavy output. The twee oriental woodwind samples on Tai Shan have certainly dated, and songwriting quality-control dips as the record progresses, but icy opener Force Ten and Open Secrets - a moving study of guardedness within romantic relationships - go deep. Elsewhere, producer Peter Collins’ vision for Mission involved overdubbing the colliery parps of Heaton Chapel, Stockport’s William Faery Engineering Brass Band. Perhaps a mix where they’re actually audible will emerge one day.

15.

Presto

(ATLANTIC, 1989)

New label, new producer. Pleased that late ‘80s Rush sounded “more like The Police than a heavy rock band”, Rupert Hine encouraged Lee to sing lower, thus aiding the intelligibility of lyrics such as that for The Pass, a powerful, empathetic anti-suicide song. Presto rations keyboards carefully, dials-up Lifeson’s acoustic and electric guitars, and, despite some proto math-rock exceptions (Show Don’t Tell; Superconductor) places renewed emphasis on ‘the song’, hence Lee sings more harmonies. Lyrically, Peart had playful, ingenious fun with the aptly-titled Anagram, writing “There is tic toc in atomic.”

14.

Rush

(MOON, 1974)

Unmistakably Zeppelin-esque, Rush’s raw, impassioned debut came on-radar when Cleveland’s WMMS FM put blue collar-friendly closer Working Man on heavy rotation. Zero record company interest hitherto had led Rush manager Ray Danniels to found Moon records for the LP’s release. Solidly helmed by original drummer John Rutsey on his only album with the band, Rush’s unreconstructed hard-rock has the horn (Need Some Love; In The Mood), opens with Finding My Way’s giant-slaying riff, and offers no hint whatsoever of the savvy reinventions to come. Lee and Lifeson’s raw power is already palpable, though.

13.

Counterparts

(ATLANTIC, 1993)

Save for their superhuman swan song Clockwork Angels, Counterparts was Rush’s last truly great record. Lifting the lid on its dry title and uncharacteristically bland cover-art reveals taut gem Cold Fire, depicting an acute all-night discussion between a couple close to separation, and soaring anthem Nobody’s Hero, in part about Peart’s gay friend Ellis Booth, who had died of AIDS-related complications. As ever, Lifeson’s instinctive guitar solos are tangibly emotive responses to the subject matter. Funky/sci-fi-ish instrumental Leave That Thing Alone and Stick It Out are also special, the latter boasting Lee and Lifeson’s heaviest unison riff in years.

12.

Caress Of Steel

(MERCURY, 1975)

Much weed was smoked while making Caress Of Steel, and you can tell. Rush’s first side-long epic The Fountain Of Lambeth charted a pilgrim’s progress from birth to death, while Tolkien-influenced oddity The Necromancer married Peart’s trippy spoken-word narrative to heavy, admirably limber riffage. Long a curious outlier of Rush’s catalogue, the LP sold poorly and took part-justified flak for artistic over-reach, yet it’s ripe for critical rehabilitation. Bastille Day’s French Revolution-inspired dynamism still thrills, while Lakeside Park - recalling a young Peart’s summer-job running fairground attractions on the shore of Port Dalhousie, Ontario - has wistful magic and a lyrical Lifeson solo.

11.

Clockwork Angels

(ROADRUNNER, 2012)

At some level Rush knew Clockwork Angels was likely their last record, and together with producer Nick Raskulinecz they pulled out all the stops. Fans couldn’t quite believe seven-minute single Headlong Flight’s old-school chutzpah: jaw-dropping instrumental interplay, a frenetic, 70’s Rush-style wah-wah solo and Peart’s heartfelt look back on all that Rush had achieved: “I wish that I could live it all again!” Sublime closer The Garden, meanwhile, revealed hard-won wisdom and offered closure: “The measure of a life is a measure of love and respect / So hard to earn, so easily burned.”

10.

Roll The Bones

(ATLANTIC, 1991)

The second of two Rush LP’s produced by Rupert Hine, Roll The Bones’ obvious stand-out is Bravado. Similar in sentiment to Rudyard Kipling’s If, and built around Lifeson’s hypnotic guitar arpeggios, the song’s music is measured and restrained. The rap bit on Roll The Bones’ title track sounds even more iffy 35 years on, it’s true, but the record’s meditations on fate, probability and luck pay further dividends on Ghost Of A Chance. “Somehow we found each other / Somehow we have stayed”, runs one couplet. Though actually about Peart and his then-wife Jacqueline, it could have been describing the magical happenstance of Rush.

9.

Fly By Night

(MERCURY, 1975)

Rivendell is quaint, Tolkien-influenced juvenilia, but with Neil Peart now anchoring-the band post John Rutsey’s departure, Rush became a power-trio of astonishing facility. They never sounded heavier than on adrenalised, super-tight opener Anthem, while By-Tor And The Snow Dog (1976 live album All The World’s A Stage packs the definitive version) was their first proper epic. Though some of the Led Zeppelin-isms which characterised their self-titled debut remained, Peart’s arrival on lyrics as well as drums ensured no more dumb pick-up songs á la Rush’s In The Mood. All this, plus In The End’s immense power-chords.

8.

Power Windows

(MERCURY, 1985)

Sequencers, triggered drum-samples and massive synth pads were go, but Lifeson’s power chords and some decidedly funky Lee bass were essential to Power Windows too. Teeming with layered detail, it’s aged far better than 1987’s less-focused Hold Your Fire. With its brilliantly bonkers Lifeson riff from 1.19, Territories made an acute critique of jingoism / isolationism which still resonates. Elsewhere, Rush explored financial politics on gung-ho opener The Big Money. Together with new producer Peter Collins, they also utilised a 30-piece orchestra and 25-piece choir while working across five different recording studios. Excessive? Definitely. Strong results? For sure.

7.

Grace Under Pressure

(MERCURY, 1984)

Mid-period Rush’s most emotionally-charged LP, Grace Under Pressure got the balance between synths and guitars about right. It took its name from a Hemingway quote and its own gestation process, which saw sometime Supertramp producer Peter Henderson co-helm proceedings at the 11th hour. Afterimage mourned tape-op Robbie Whelan, who had died in a car crash, while the astonishing Red Sector A was Peart’s heartfelt, anonymised account of Lee’s Holocaust-survivor mother Malka’s interment at Auschwitz. An agitated, humane and passionate record, Grace also explored tensions between world superpowers on Distant Early Warning.

6.

Hemispheres

(MERCURY, 1978)

With hindsight, Hemispheres’ Apollonian and Dionysian-concept embroiled Side One outstays its welcome. Despite some fine moments (witness Lifeson’s barnstorming solo at 6.24 and the song-suite’s acoustic coda), it’s also stymied by a key too high for even Geddy Lee to sing, as he later acknowledged. Turn instead to concise, powerhouse Circumstances and Rush’s greatest instrumental, La Villa Strangiato. Part inspired by a nightmare Lifeson had, the latter was subtitled “an exercise in self-indulgence”, but wasn’t, really. Initially, Rush thought its many virtuosic sections would preclude live performance. Not so. They nailed ‘em.

5.

Permanent Waves

(MERCURY, 1980)

New decade, new-ish Rush. UK Number 13 single The Spirit Of Radio proved a challenging dance for Legs & Co. on Top of the Pops, while Entre Nous, about the limits of empathy, reflected Peart’s growing acuity re the minutiae of human relationships. Deep-cut ballad Different Strings was also masterful, guest pianist Hugh Syme - also Rush’s cover art mastermind from 1975 onwards - bringing colour before Lifeson’s feral, slow-evolving solo. Like Peart’s lyrical focus, Lee’s voice was also changing. Fan favourite Freewill was the last Rush song he would sing at the very top of his range.

4.

Signals

(MERCURY, 1982)

Signals was the final Rush album produced by Terry Brown, who’d also helmed their previous eight. Its quality-controlled songwriting embraced nascent digital tech on synth-driven study of suburban ennui Subdivisions, while Lifeson’s guitar sound became more processed, a little more abstract. Electric violinist Ben Mink guests on avowed classic Losing It, wherein Peart’s lyric sketches the slow, painful fade of artistry due to ageing or ill-heath. Poignantly, this would be the drummer’s own fate prior to his 2020 passing. The Analog Kid and Chemistry are ace too; thoughtful, arresting songs which see Rush embrace new-wave tropes.

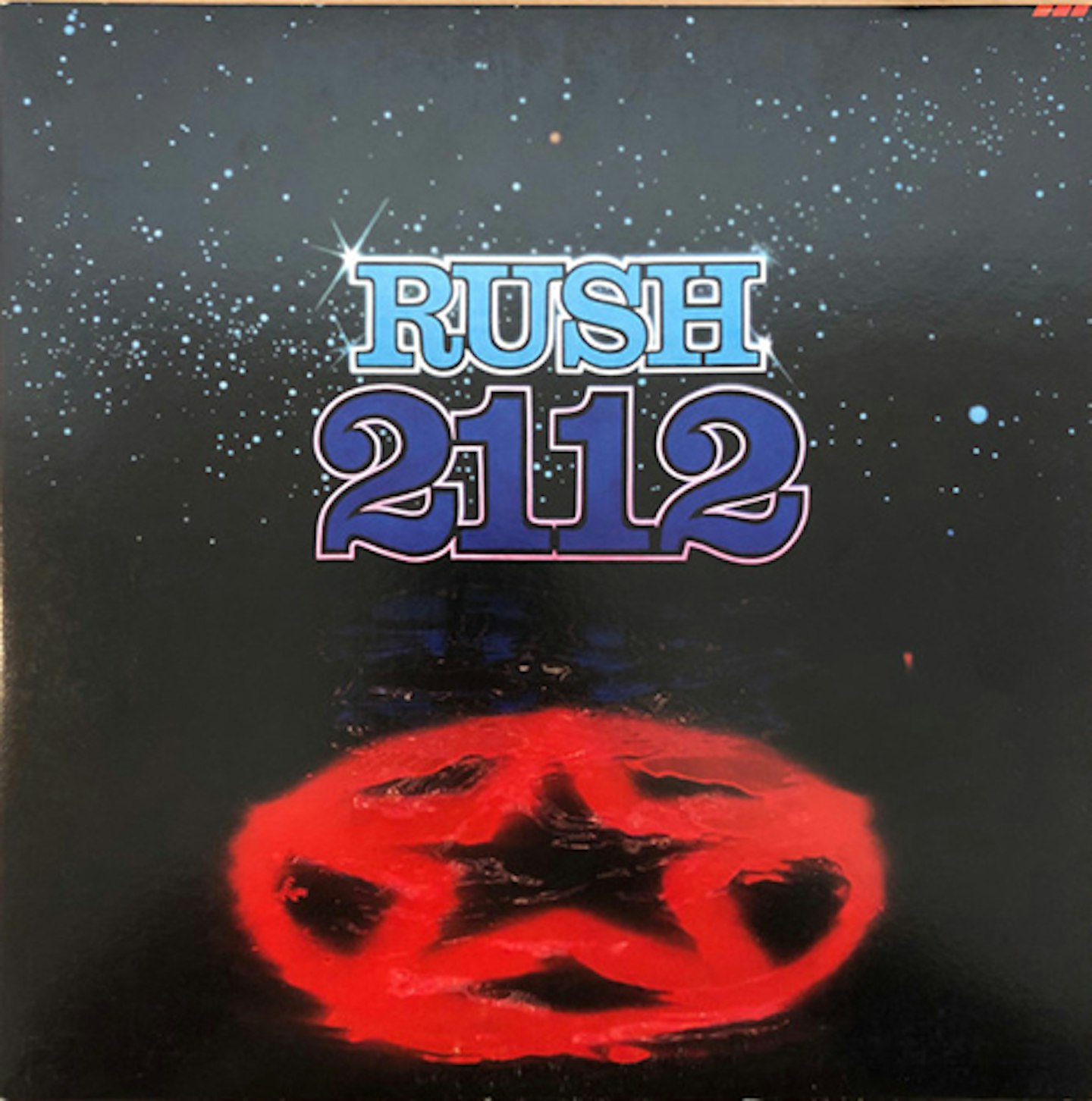

3.

2112

(MERCURY, 1976)

1975’s commercial nadir Caress Of Steel necessitated 2112, the high-energy mother of all comebacks. Partly a futurist concept LP set in the dystopian city of Megadon, where music has been banned, Side 1 borrowed from Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture and Ayn Rand’s novella Anthem as Rush battled those killjoy Luddite priests of The Temples Of Syrinx. Non-conceptual Side 2 packed weed connoisseur’s travelogue A Passage To Bangkok, early gem Something For Nothing, and Lifeson’s classy, pinch-harmonic-laden solo on The Twilight Zone. Resplendent in white silk kimonos on 2112’s back-sleeve, Rush were hot property again, wilder instincts vindicated.

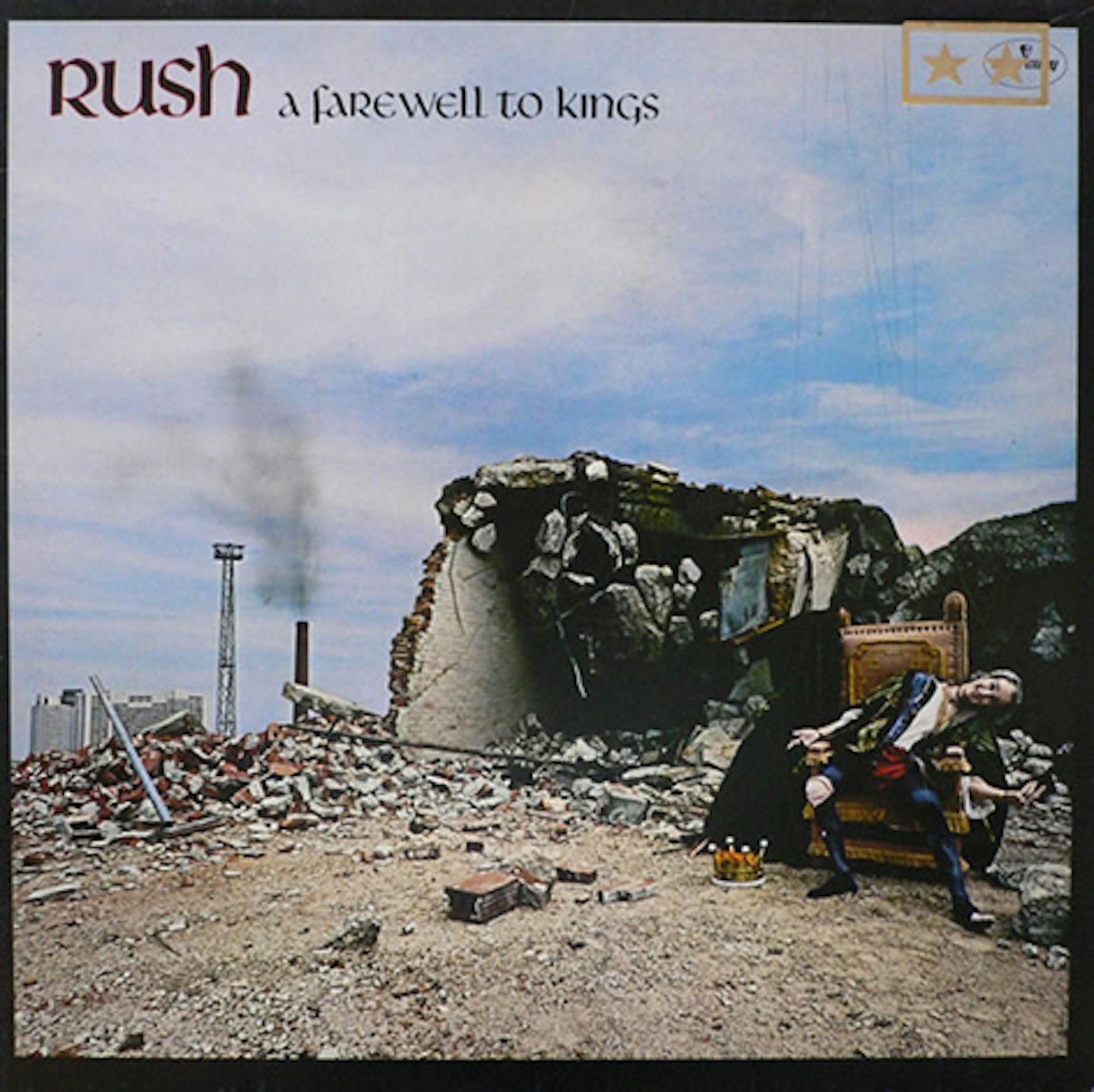

2.

A Farewell To Kings

(MERCURY, 1977)

Featuring tubular bells and Lee and Lifeson on double-necks, 11-minute, Samuel Taylor Coleridge-inspired epic Xanadu was Rush at the peak of their pomp. But Kings also featured succinct, altruistic anthem Closer To The Heart, a singalong fave at gigs thereafter. If Lee’s increasing use of Minimoog and he and Lifeson’s Taurus bass pedals spoke of a band in stylistic transition, recording the LP at Rockfield studios in Wales spoke of Rush’s growing international appeal. Bookended by Lifeson’s courtly classical guitar, Kings’ title track remains a true classic, Lee’s powerful tenor operating at altitude.

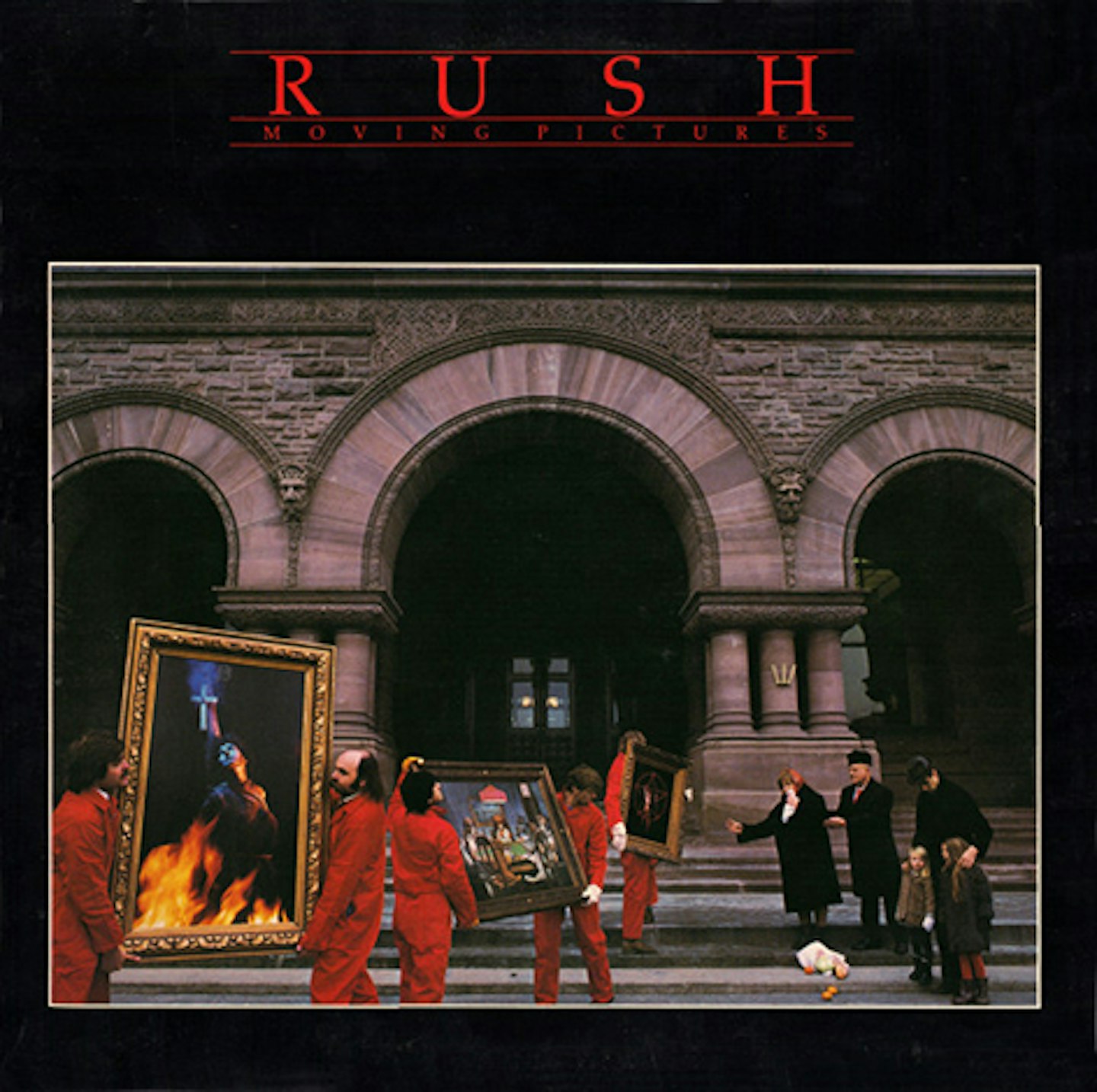

1.

Moving Pictures

(MERCURY, 1981)

Propelled by air-drummer fave Tom Sawyer (don your Zildjian finger-less gloves at 2.31), Moving Pictures took Rush out of theatres and into stadia. “Our immediate financial worries disappeared”, recalled Lifeson of this UK and US Number 3. Vital Signs’ nodded at The Police. Limelight was Peart’s lucid debunking of fame; Witch Hunt his ever-pertinent take-down of prejudice. Image-wise, Rush’s stack-heels and waist-length hair had long-since ceded to mullets and skinny ties, but their metamorphosis wasn’t quite complete. The Camera Eye’s nod to New York City and London’s vibrancy had old-school élan, time-signature changes and all.

Photo: Fin Costello/Redferns