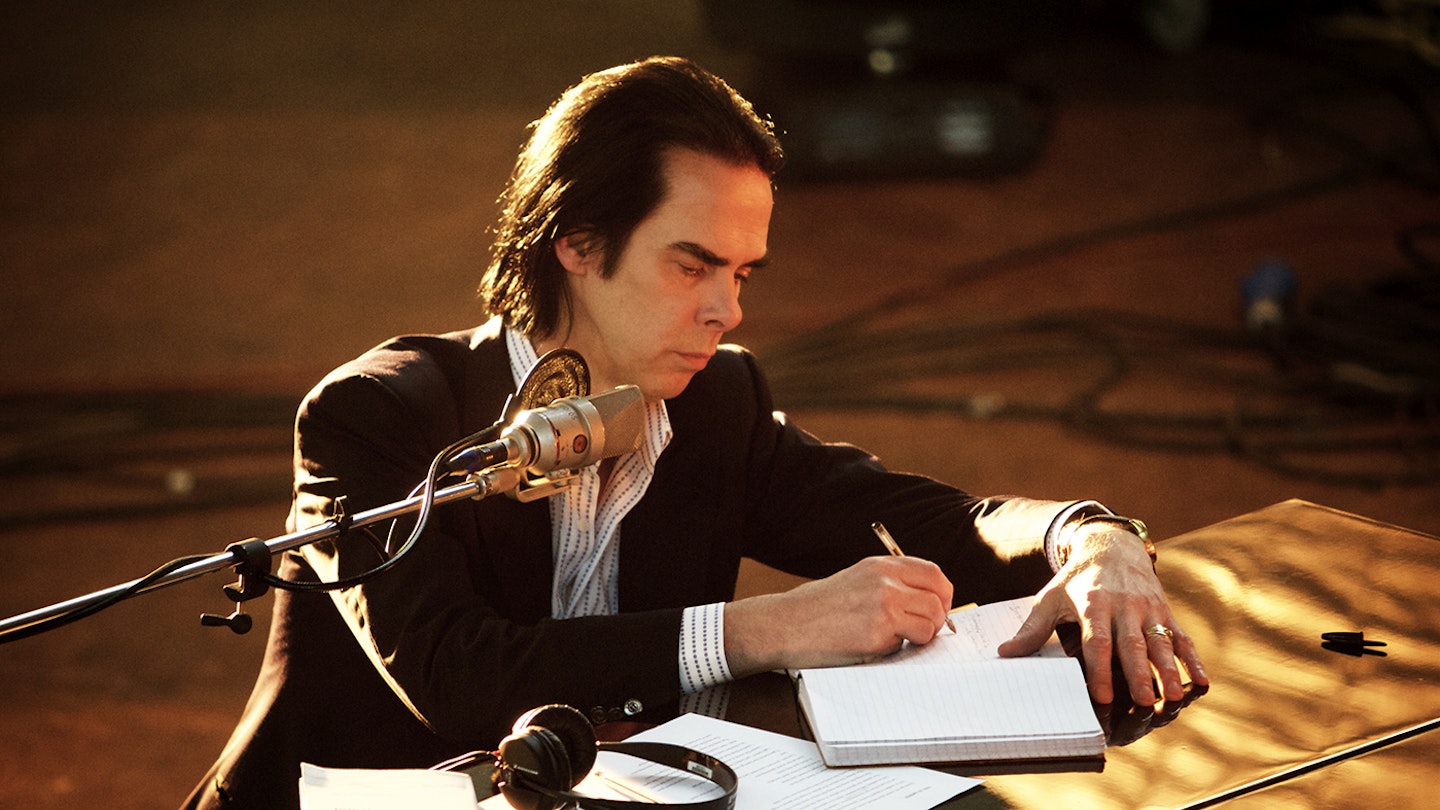

Portrait: Kerry Brown

Back in the early 80s the nihilistic, fright-wigged peperami of early performances by theatrical Melbourne spleen-punkers The Birthday Party appeared on a collision course with destruction, and when hard drugs notoriously entered the mix, there was writing of sorts on the wall. And yet Nick Cave has turned into one of our most consistent artists, evolving new aspects, plumbing new depths and finding more areas of life and love to explore in his unique, grimly wry baritone.

These days, with the man himself long since clean and serene, most years bring new gold from the Cave mine, as his group, The Bad Seeds, have morphed slowly from the savage Weimar avant-bluesmen of 1984 debut From Her To Eternity into something far deeper, wider in scope, surviving potentially crippling line-up upheavals (notably, the departures of Blixa Bargeld and Mick Harvey) as they rage, rage against the dying of the light. Here, MOJO’s team of experts have compiled what we believe to be the definitive list of Nick Cave's greatest ever songs…

30.

Stranger Than Kindness

(from Your Funeral… My Trial, 1986)

A keynote Bad Seeds song not written by Nick Cave.

In 2010, Cave declared Stranger Than Kindness his favourite Bad Seeds song. That it was written (with Blixa Bargeld) by Anita Lane, Cave’s erstwhile girlfriend and catalyst for some of his key ’80s work, clearly heightens its desolate tension, while Bargeld’s layered cheese-grater guitar and Mick Harvey’s brushed drums amplify the dreadful sadness of lyrics like “You caress yourself/And grind my soft cold bones below”. As Lane later explained: “It was just how I felt one day.”

29.

Breathless

(from Abattoir Blues/The Lyre Of Orpheus, 2004)

Mr. Bluebird lands on Cave’s shoulder. At least on first play.

Strummy acoustic guitar and Warren Ellis’s wonky flutes usher Cave into a Disney Technicolor world with fields filled with “happy hooded bluebells” and fish popping their heads up from the “bubbling brook”. On the surface, his heart is swelling with so much love that it’s fit to burst. But then darkness falls and Cave reveals that he’s “without” the object of his affections; that’s why he’s obliged to seek their spirit in nature. An unusually chirpy song of loss, then.

28.

Leviathan

(from Ghosteen, 2019)

Making the unbearable transcendental.

Has anyone sung the word “love” more often and with more shades of meaning? Here it’s the flotsam you cling to when all is wrecked, when you sit for hours in a parked car by the sea, knowing only that “I love my baby, and my baby loves me”. Around Cave’s battered mantra, music looms out of glower and nuages, Kaushlesh Purohit’s sparing tablas underpinning a swelling synth melody that becomes an angel choir that tears at your heart. And the Leviathan? It’s the elephant in the room.

27.

Do You Love Me (Part Two)

(from Let Love In, 1994)

The encyclopaedia of taboo subjects reaches the 'p' word.

A song about uneven power relationships so good, Cave included it twice on Let Love In: first as a ramalam, with the singer pitted against a prospective wife; the second slowed to a Spaghetti Western death march, rewritten as the account of a young boy being sexually abused in a cinema. Cave channels Peter Straub’s source story, The Juniper Tree, into finely-wrought lines: “The clock of my boyhood was wound down and stopped.” Plus, a significant arrival, as Warren Ellis’s violin makes its Bad Seeds debut.

26.

Jesus Alone

(from Skeleton Tree, 2016)

High-voltage surveillance of all terrestrial life.

The coincidence between the death, in 2015, of Cave’s son Arthur and the opening lines here remains chilling: “You fell from the sky / Crash landed in a field / Near the River Adur.” Two plummeting figures, both in Sussex. Yet the song was written in 2014. Distorted drones underpin a narrative that moves on to Tijuana druggies and African doctors. The compelling physics-lab feel and a fellow album track called Magneto suggest an art-rock Marvel hero. Super power: omnipotent horizon-wide observation.

25.

No Pussy Blues

(from Grinderman, 2007)

Oo-er! It’s Grinderman’s Carry On Midlife Crisis…

If his songs are miniature movies, here’s the sex comedy: pushing 50, the narrator, who happens to be a goatish rock star with a moustache, realises that young women find him profoundly resistible, despite his posing and flattering like the young blades do, over music taut and raging, Warren Ellis giving it some Rowland S. Howard on two brutalist solos. In 2008, a digital-only remix EP added novel visions of Cave as mooby and receding disco-dancing dad, at once confessor and reveller in his shame.

24.

More News From Nowhere

(from Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!!, 2008)

Hair-dye enthusiast revealed as face of Grecian 2008.

This spiraling narrative supposedly mirrors Homer’s The Odyssey, with a contemporary cast taking the place of Poseidon and pals. Textual analysis from classical scholars is pending, but rock dissection identifies both Van Morrison’s ex-wife Janet Planet and Deanna, title character of the 1988 Cave song with shared musical content. The free-associative lyrical frisson is grounded by a beautiful bell-like guitar figure and a lovely, chugging impetus; nigh on eight minutes here, but feeling like it could roll on forever.

23.

Stagger Lee

(from Murder Ballads, 1996)

The legend of a Missouri bad-ass gruesomely reimagined

After black pimp ‘Stag’ Lee Shelton shot Billy Lyons for swiping his hat in St Louis in 1895, the tale was recounted in numerous folk songs, before landmark takes by Mississippi John Hurt (1928) and Lloyd Price (1959). Recording in Melbourne for Murder Ballads was almost complete when an update was suggested by sticksman Jim Sclavunos. Over Martyn Casey’s predatory bassline, Cave duly revamped it for a blood-thirsty late-20th-Century, adding fresh twists, including a lippy barman slain, and sumptuously nasty dialogue.

22.

City Of Refuge

(from Tender Prey, 1988)

Widescreen call to arms provides “difficult” fifth LP’s secret weapon

It rolls into focus, inspired by Blind Willie Johnson, out of a heat-haze of howling hillbilly harmonica and acoustics wristed by Bargeld and Kid Congo Powers in readiness for whatever wicked entity this way comes. Thomas Wydler’s snare and Roland Wolf’s organ rattle and hum as Cave’s paranoia shape-shifts into exodus. Run! From what? Unspecified bad deeds? Gutters “running with blood” that will “spew you out”, its diabolically encroaching walls of dust seemed to find purchase anew after 9/11 – “You better run and run and run…”

21.

The Carny

(from Your Funeral… My Trial, 1986)

A Brechtian allegory of the touring life ensnares MOJO’s Andrew Male…

Nick Cave first entered Hansa Studios in October 1982 to record The Birthday Party’s Bad Seed EP. He was there six months later for the band’s flailing deranged abdication, the Mutiny! EP. Situated on Kothener Strasse, adjacent to the Berlin Wall, this former builders’ guild hall had, from 1933 to 1945, housed Joseph Goebbels’ Reichsmusikkammer which promoted “good German music” and helped suppress “degenerate” works by jazz musicians, modernists and Jewish composers. This knowledge caused The Birthday Party great hilarity, prompting them to adorn both EPs with swastikas. “It was a belly laugh,” Mick Harvey told author Ian Johnston. “We were in this horrendous historical environment. The swastika was an obvious reference to that [and] it just came in, rather than suppressing it, like a lot of Germans would.”

However, during the Weimar years the building was also home to an art gallery owned by George Grosz, a Neue Sachlichkeit artist who specialised in depicting criminals, gangsters and outsiders, characters who dwelled outside the normal conformist life.

“Cave summons images of flapping bird-girls, dwarves with faces like dying moons.”

Three years later it’s this Berlin, and that of Grosz’s contemporaries, playwright Bertolt Brecht and composer Kurt Weill, that occupies the forlorn lurching soul of Cave’s early narrative epic. Overflowing with the same baroque gothic language that bulged the pages of his then still unwritten novel, And The Ass Saw The Angel, the song tells an uneasy Brechtian tale of a troupe of circus performers abandoned by one of their own who kill and bury his “bow-backed nag”, Sorrow.

With Mick Harvey building a mood of bilious sideshow disquiet on organ, glockenspiel, xylophone and the plectrum-plucked guts of a grand piano, and Blixa Bargeld voicing the ruthless Boss Bellini (who shoots the horse before declaring “the nag was dead meat/We can’t afford to carry dead weight”) this sickly, weaving song is, of course, an allegory for the Bad Seeds, a group of wearied entertainers sloughing off their burdens, and saying goodbye to an old way of life.

Augmented by Bargeld’s mournful howling guitar (intended to emulate the dying squeals of Sorrow), Cave’s trail-whistle harmonica, and his multi-tracked voice summoning images of flapping bird-girls, dwarves with faces like dying moons, and dead horses floating on the rain-sodden earth, it is, of course, a nightmare vision of debased humanity and one that, as depicted in Wim Wender’s 1987 film, Wings Of Desire, can have an almost hypnotic hold on an audience. But it is also a blackly comic fairy tale, a self-parodic reworking of the majestic Tupelo, and a curdled romantic vision of cursed touring vagabonds, led by a ruthless taskmaster and doomed to keep on moving through the beating rain and onto higher ground.

20.

Push The Sky Away

(from Push The Sky Away, 2013)

Soul-stoking, slow-burning mantra for creative endurance.

From an album inspired by Google search whims, the title-track is spare, elegiac and just a bit woo-woo; poignant poetry for transcendental YouTube yoga. “You’ve gotta just keep on pushing/And push the sky away,” chants Cave. A children’s choir softly repeat his mantra as Warren Ellis’s cosmic, ruminating synth patterns rise and fall in heartbeat time. Peaking with Cave’s ultimate affirmation: “And some people say it’s just rock’n’roll/Aw, but it gets you right down to your soul.” Amen.

19.

Saint Huck

(from From Her To Eternity, 1984)

Foreshadowing Stagger Lee, a viciously Weimar Mississippi murder ballad.

His parents an English teacher and a librarian, bookworm Cave wrote compulsively and, no longer lyrically cramped by sharing the spotlight with Rowland S Howard’s guitar, he uncorked the ink on The Bad Seeds’ debut LP, the murder ballad Saint Huck blueprinting many more to come. Inspired by his recent stay in Berlin, Cave’s theatrical Americana grimoire updates the Bertolt Brecht of Happy End and Mahagonny, eliding and martyring Mississippi icons Huckleberry Finn and Elvis Presley to a brooding bass line from hell’s own pit band.

18.

Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!!

(from Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!!, 2008)

New Testament, New York, new sensations

What if Lazarus resented his resurrection? What if he became famous, decadent and utterly lost? What if he missed the grave? Cave rerouted a Grinderman demo called Rockabilly Lazarus via Larry Sloman’s Houdini biography and Lou Reed’s street-hassling New York stories, then soldered it to a relentless industrial blues. His persona is defrocked priest-turned-stand-up comic. The first time he sang, with a camp shudder, “Oh, poor Larry”, bassist Martyn P Casey laughed so hard that he couldn’t play.

17.

The Weeping Song

(from The Good Son, 1990)

Nick and Blixa go the full Ken Dodd.

As Walker Brothers-balmy as a crate of triple-ply tissues, The Weeping Song delivers abundantly on its title’s premise: the women are weeping, the men are weeping, everybody’s weeping. Nick Cave, too, sounds drenched in lachrymose, as big daddy Blixa lays on him the hardest truth that “the children… are merely crying, son… True weeping is yet to come.” Arranged like a traditional folk round, The Weeping Song is a paragon of new era Bad Seed blues.

16.

Bright Horses

(from Ghosteen, 2019)

Caught between imagination and reality, a writer chooses faith.

Recording The Boatman’s Call in 1996, Nick Cave demoed a sentimental ballad of assurance for son Luke, entitled Sheep May Safely Graze. Afterwards, Blixa Bargeld told Cave, “Sing that to your boy. Spare the world.” But people change. So does the world. We need reassurance. To a simple Chopinesque berceuse and wordless chorale, Cave articulates the uneasy necessity of faith. The bright horses of our sentimental imagination may not be real, but that doesn’t negate our belief in them, or in the simple fact that our loved one’s coming home on the 5:30 train.

15.

Deanna

(from Tender Prey, 1988)

Bonnie And Clyde goes rollicking garage-punk.

There was a real Deanna, who returned to the Cave narrative when One More Time With Feeling director Andrew Dominik revealed in MOJO 278 he’d dated her three months after the singer. ‘Her song’ authentically details her mother’s “Ku-Klux furniture”, covered in white sheets while the two loved-up hell-raisers house-sat for her, but otherwise it’s a lurid psychosexual fantasy of plotted robberies and killings. The organ-dripping accompaniment evolved from a jam on The Edwin Hawkins Singers’ Oh Happy Day – sweet sacrilege.

14.

Skeleton Tree

(from Skeleton Tree, 2016)

A numbed fugue finds crumbs of comfort in the chaos of existence.

Its parent requiem’s closing song, this bruised, haloed distillation of grief is Cave at his most Orphic, discerning the undiscovered country beyond and the son he had lost. To brushed drums, piano and washes of electricity, sparing references to a “jittery TV”, fallen leaves and a candle in a window articulate loss and non-loss, while the payoff “Nothing is for free” reveals the human condition in all its tragedy and beauty. The outro is lent haunting charge by an unidentified woman’s voice.

13.

People Ain’t No Good

(from The Boatman’s Call, 1997)

Hymn to misanthropy, popular with kids.

“They never do what you want ’em to/Cuz people ain’t no good.” So yelped Lux Interior on 1986 Cramps track, People Ain’t No Good. Cave’s never said it inspired his funereal ode to solipsism and romantic failure. Nor did he admit to the influence of Auden and Larkin in this very English tale of love defeated by time. The elegiac soundtrack to Shrek’s rejection by Princess Fiona in Shrek 2, this is probably responsible for a whole new generation of doubters and pessimists.

12.

We Call Upon The Author

(from Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!!, 2008)

Totally Lit.: Cave demands a cosmic edit.

Playing the embittered writer souring in his “bolthole”, Cave turns the universe into one immense literary feud. Over a squalling, rogue-typewriter groove, he criticises Charles Bukowski (“a jerk!”) and Wallace Stevens, although his chief nemesis is God, an author whose plot twists (“Third World debt/Infectious disease”) have tipped into the grotesque. “Prolix! Prolix! Nothing a pair of scissors can’t fix!” yelps Cave, mocking his own use of “myxomatoid” and “jejune”, maybe, but also demanding one last scything edit of an

incoherent world.

11.

Jubilee Street

(from Push The Sky Away, 2013)

A rebirth on Brighton’s dark side. MOJO’s Victoria Segal takes a walk…

“There’s a certain type of song that I write, and that gets the kind of Bad Seeds treatment,” says Nick Cave during The Making Of Push The Sky Away, a short film made as the band recorded their 15th album in the wisteria-draped idyll of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. “It’s important for us to tear away from that way of going about making songs.” Swerving old patterns paid off: after Grinderman’s boys-together spree and the hectic visions of Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!!, the looped, spacious Push The Sky Away felt like a crucial resetting of the Bad Seeds’ clock, a powerful, self-willed rebirth.

No song embodies this process as clearly as Jubilee Street. Named after a road in the singer’s adopted hometown of Brighton, it starts like classic Cave noir – there’s a girl, she’s called Bea, she’s a prostitute with “a history but no past”. Quickly, though, it escapes the red-light murk, culminating in an ecstatic, breathless act of transcendence: “I’m transforming/I’m vibrating/I’m glowing/I’m flying/Look at me now.”

It’s not just the song’s damaged narrator in flux: this is the sound of the band splitting their grimy Grinderman skins, rejuvenating, reshaping. Based around one of Warren Ellis’s deceptively languid riffs, it repeats and repeats, almost imperceptibly building up the pressure until the metamorphosis is complete.

“This is the sound of the band splitting their grimy Grinderman Skins.”

There is a dark story here: the narrator visits Bea, she vanishes, “the Russians move in” and there’s a hint of blackmail and incrimination – “the problem was she had a little black book/And my name was written on every page”. More unnerving is hearing Cave sing “I got love in my tummy”, as disturbing as the presence of the Ecole Saint Martin children’s choir – a flash of innocence in a song scarred by experience. Yet the hard-boiled storyline cracks: the narrator’s burdens are replaced with “a foetus on a leash”, a nightmarish image of rebirth. He sheds his guilt, his possessions and ultimately, his body: “I am alone now/I am beyond recriminations”.

Cave has said he struggles with “the tyranny of the narrative”, storytelling songs that have one thread to pull. “Dylan wrote like that,” he said in 2013. “I can’t bear them, to be honest – you know, ‘The Ballad Of Such And Such’… you hear it once and you’ve got the gist of it.” Jubilee Street, titled in sly opposition to Desolation Row, breaks those shackles like the narrator sheds his Sisyphean “wheel of love”, his “10 tonne catastrophe on a 60 pound chain”.

So destabilising is Jubilee Street, Cave wrote a song about its creation – Finishing Jubilee Street, where, like a medieval mystic, he puts down his pen on Bea’s world and spins into a dream where he has a young bride called Mary Stanford. That’s what Jubilee Street can do, it implies – change dreams, shift reality. Look at it now.

10.

Ghosteen

(from Ghosteen, 2019)

How a master songwriter came so far for beauty

If the challenge that illuminates Ghosteen is how “to write beyond the trauma”, it found its purest manifestation in the 12-minute title track. The slow-motion blend of strings and synths is both ominous and cocooning, like Scott Walker’s Farmer In The City remixed by Cluster, while the chorale that arrives halfway through is almost unbearably lovely. A reminder that opposites – “This world is beautiful” and “the past with its fierce undertow won’t ever let us go” – can co-exist, in spite of everything.

9.

Straight To You

(from Henry’s Dream, 1992)

A love song for the end of the world.

The promo clip, where the Bad Seeds variously accompany a fire eater, a belly dancer and a magician, in some kind of theatre-cum-crypt, is pretty daft. But the song? A Cohenesque hymnal with the kind of organ riff Al Kooper played for Dylan, here invocations of bad-Bible cataclysm prelude something more powerful still - a giving in to the ultimate mystery of love. This metaphysical revolt is realised with such devastating clarity it becomes an intimate mass moment to rival any in rock.

8.

Mutiny In Heaven

(from Mutiny EP, 1983)

If heroin is Heaven, a thrillingly impenitent mutineer’s shanty.

By Cave’s own reckoning the summit of his Birthday Party songwriting at the very moment they were morphing into The Bad Seeds (Blixa Bargeld surreptitiously replaced Rowland S Howard’s guitar parts), Mutiny In Heaven was penned overnight under pressure to fit a bass line too good to waste. In unacknowledged riposte to The Velvet Underground’s Heroin, far from “feeling like Jesus’ son” Cave’s “threadbare soul teems with vermin” and scabrous Catholic rebellion as he bails from Lou’s “kingdom” with a gleeful piratical swagger. “Utopiate”, indeed.

7.

(Are You) The One That I’ve Been Waiting For?

(from The Boatman’s Call, 1997)

Let love in: Cave seeks and finds on epic ballad.

There is a woman in this love song – she wears a coat, she’s crying – but her physical presence is almost entirely theoretical, an embodiment of the myth of “the one”. Cave’s stately, beautiful imagery of war, geology and astrophysics – plus a reference to the Sermon On The Mount – blows up romantic yearning onto a heroic scale, drums and vocal just slightly too slow to echo the exquisite ache of delayed gratification. A great marble monument to longing, it’s a spectacular pedestal for the right person.

6.

Red Right Hand

(from Let Love In, 1994)

Milton provides killer title. Peaky Blinders feel the benefit.

Amid a bowel-freezing death-knell, a moody bass riff and wild oscillator abuse by Cave himself, this whisper-to-a-scream Bad Seeds set cornerstone chillingly portrays a Mephistophelean figure whose money-grabbing occurs at any human cost – his ‘red right hand’ the evidence of his bloody misdeeds. The third verse implies a drug dealer to whom Cave, then mid-rehab, may have handed over ‘stacks of green paper’; the fourth suggests a smarmily amoral TV host à la Jeremy Kyle. All told: not a nice guy.

5.

The Ship Song

(from The Good Son, 1990)

Romantic reconciliation, as willingly lost battle.

Cave’s got Anita Lane’s name tattooed on his right arm, beneath a dagger-impaled skull-and-crossbones. An on-off item and occasional writing partners from the late ’70s, their lively arguments often ended with Cave advising her to do her absolute worst and move on. Set in a Sylvan landscape with the singer harmonising with himself, this graceful, oxygenated ballad remembers this and acknowledges the garment-rending end of the affair, as it waltzes into the twilight. Often covered, impossible to match.

4.

Tupelo

(from The First Born In Dead, 1985)

Elvis is born. The end is nigh!

On April 5, 1936, the fourth deadliest tornado in US history hit Tupelo, Mississippi, smashing homes to matchwood and driving pine needles into the trunks of trees. Hundreds were killed, but among the spared was Elvis Aaron Presley, age 1. Nigh on 50 years later, Tupelo’s tribulation becomes rock’n’roll’s creation myth – Elvis transformed by a babbling, possessed Cave into messiah or anti-Christ, his stillborn twin a ghastly sacrifice, while Harvey and Adamson’s rumbling cloud of bass and drums promise a terrible judgment.

3.

From Her To Eternity

(from From Her To Eternity, 1984)

Houseshare horror lodges in the mind.

Post-Birthday Party, Cave said he was no longer “kicking people in the teeth”; instead, he delivered a sickening gut-punch with the title track of the Bad Seeds’ debut. Written with Anita Lane, this fetid tale of obsession unfolds like a nasty jailhouse confession, the narrator over-sharing his fixation on his weeping upstairs neighbour. The band performed it in Wim Wenders’s Wings Of Desire, but it belongs somewhere infernal, rictus piano and spasming guitar mirroring a man moving towards an atrocity, the killer inside coming out to play. VS

2.

Into My Arms

(from The Boatman’s Call, 1997)

Cave’s greatest love song: a wounded beauty, with a dark, desperate undertow.

Cave was wounded when he wrote Into My Arms – the breakup with Viviane Carneiro, the mother of his son Luke, and his failed romance with Polly Harvey. Plus he was in rehab, in Somerset, trying (but failing, this time) to kick heroin. On Sundays the patients were allowed out to go to church. So Cave went to church. Back in the clinic, sick from withdrawal, he quickly wrote the words to the melody that was already in his head. Interpolating love, loss longing and God. The subject, as Cave said in a lecture on songwriting a year later, ultimately of all love songs. The song is a beauty, but a wounded beauty, with the dark, desperate undertow of a man calling in a void, praying to someone he knows is not there. Born form pain, it was, and remains, his greatest love song.

1.

The Mercy Seat

(single, 1988)

Guilt or innocence? Or is it just the human condition? Whichever, MOJO’s Keith Cameron is transfixed…

On May 10, 1998, Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds squeezed into the small London premises of independent radio station XFM and recorded four songs for broadcast. It was release day for The Best Of Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds, but XFM’s studio constraints pointed a reduced group configuration – Cave, Martyn Casey (bass), Mick Harvey (guitar), Conway Savage (piano), Thomas Wydler (drums) – towards the acoustic arrangements of Cave’s most recent studio album The Boatman’s Call, from which Brompton Oratory, Into My Arms and Lime Tree Arbour were played. To close the session, however, Cave returned to The Mercy Seat, a 10 year-old song about killing and guilt. History had already proven it exceptionally malleable, yielding acoustic ensemble versions, solo piano ballads, even a spoken word performance at the 1996 Poetry Olympics. The original recording was an intemperate storm; here it became a regretful elegy. Regardless of shape, The Mercy Seat is Nick Cave’s most-performed song, his masterpiece. The numbers don’t lie. As he told MOJO in 2017: “There’s a reason why we’ve played that song at every gig since it was released.”

Today we associate the song with epic grandeur – even Cave has suggested it’s his My Way – so returning to the source brings surprises. Released in June 1988 as a prelude to the Bad Seeds’ fifth album Tender Prey, The Mercy Seat is alchemised from industrial turbulence, mechanised loops of Mick Harvey hammering the E and B strings of a bass guitar with a drumstick. Having worked on the lyric over a period of six months, Cave’s initial motivation when entering Hansa Tonstudio in September 1987 was to create a song with the same relentless predatory threat of Suicide’s Harlem. Less than a year after its release, however, he had begun essaying acoustic treatments, a template he would return to over the next two decades. Today, dispatched with widescreen symphonic power by the current Bad Seeds, performances of The Mercy Seat foreground its melancholy over the infernal vortex.

It’s that side of The Mercy Seat which attracted the imprimatur of a legend. When Cave heard that Johnny Cash was covering The Mercy Seat, he reportedly said: “Man, I can die now.” But unlike some other songs in his American Recordings series – Nine Inch Nails’ Hurt, for instance – Cash doesn’t truly conquer The Mercy Seat for himself. The efficacy of The Man In Black’s version depends on its relationship to Cave’s, as a sort of playful rejoinder to the original’s brimstone ambiguity. In Cave’s telling, the narrator is “nearly wholly innocent” of whatever crimes have led him to “Dead Row”; Cash, by contrast, declares himself “totally innocent”. Whereas Cash can’t seem to get inside the song’s skin, Cave is buried troublingly deep, progressively tainted by its malevolent spirit, complicit in each mounting layer of contradictory testimony: “And anyway I told the truth/But I’m afraid I told a lie.”

"The Mercy Seat has become so indelible because we all feel the weight of its preoccupations."

Cave wrote The Mercy Seat concurrent with his novel And The Ass Saw The Angel, while also immersing himself in the story of Australian outlaw Ned Kelly and hard-boiled crime literature, a prelude to his role in John Hillcoat’s brutal prison drama Ghosts… Of The Civil Dead. A copious intake of amphetamine and heroin compounded his volatile mood, and possibly contributed to the fluctuating lyrics, itself an aspect of the protagonist’s conflicted relationship between good and evil. Does the song’s ongoing evolution mirror the author’s accommodation with the person he was when he wrote it?

Beyond question, however, is that The Mercy Seat has become so indelible because we all feel the weight of its preoccupations. This is far more than just a song about a bad guy dying in the electric chair. Amid the crushing totality of its seven minutes and 18 seconds, from queasy-voiced opening, through minor key expository verses and thence onwards to its epic resolution, The Mercy Seat plays out like a hysterical *danse macabre*, like The Seventh Seal soundtracked by Death’s pick-up band. Amid all the chaos and accumulated sonic distress, via Blixa Bargeld’s needling guitar and strings that flail the senses like the surreal visions which haunt the condemned killer – “The face of Jesus in my soup”; “A hooked bone rising from my food” – The Mercy Seat is a lament for man’s inhumanity. The sorrow is felt most keenly in the pathos of Christ, the “ragged” (or sometimes subsequently “wretched”) stranger, a carpenter quite literally nailed by the tools of his trade. How do we judge the institutionalised killing of a man whose guilt is presented to us as a question of perspective? Where’s the motive? Where’s the proof? Who weighs the good hand against the evil? Head shaved and fixing to die, in a single verse he’s both pitiable (“Like a moth that tries/To enter the bright eye/I go shuffling out of life”) and insouciant (“And anyway I never lied”).

The song’s final five minutes simply comprise its de facto chorus, an eight line descending stanza that begins, “And the mercy seat is waiting” (or “burning”, or “glowing”, or “smoking”), repeated, 14 times, in a litany of reckoning for the day that everyone must face. Some 10 years ago, Blixa Bargeld, the Bad Seed who stood at Cave’s side during the feverish Berlin period from whence the song emerged, said: “I know that Nick sometimes used to say, ‘When I die, I can say I wrote The Mercy Seat’. It must have been really important to him.”

The latest issue of MOJO is on sale now! Featuring Nick Cave, Bob Dylan, Kate Bush, Paul McCartney, Paul Weller, Arctic Monkeys, Lana Del Rey, Blur, Oasis and the artists who have shaped MOJO's 30 year history. More info and to order a copy HERE!