Longhaired hippy dreamer, proto-punk rocker, experimental synth-explorer, godfather of grunge, still raging anti-war polemicist... Since he first emerged as part of Buffalo Springfield in 1966, Young has taken on every one of these guises, sometimes several at once. But one constant remains – as soon as the world has begun digesting the latest Neil Young creation, the man himself will have moved on.

The passage of time is a recurring theme in Young’s music. He’s a master at capturing a moment, his references to the past and questions about the future placing the listener directly in the song. Past and present, the end and the beginning, young and old, the artist and the audience, the electric and the acoustic; conflicts like these lie at heart of his best records. Whether he renders them using the upper registers of a blazing Les Paul or an acoustic guitar, a piano and that vulnerable/defiant voice, or even a vocoder and a keytar, Young has always made music that comes from the very centre of his being.

It's why his songs have resonated not only with his fans over the decades, but with other musicians who remain in awe of his continued creative chase. A chase that, as his latest album Talkin To The Trees shows, continues to turn up fresh treasure long after the gold rush was supposed to have passed. As Neil and The Chrome Hearts get ready to headline this year's Glastonbury Festival (you can read MOJO's full on-site report HERE) a selection of stars - many of whom have played on those very same tracks - pick their own personal favourites for MOJO's rundown of Neil Young’s 50 greatest songs…

50.

Music Arcade

(Broken Arrow, 1996)

Neil’s lowest-fi slice-of-life: “Have you ever been lost?”. As selected by Giant Sand’s Howe Gelb.

“Just weeks before flood waters [in Pennsylvania] would come and spill six feet over our roof, I had just drawn a mural on my bedroom wall of my favourite bands at the time. Neil was there amongst the Stones and Zeppelin. Funny thing was, when we re-entered our devastated home, those walls had been protected by the mattresses that washed up against them. There I stood in my destroyed world, stanky river mud clotting the walls and ceiling and ankle-deep ooze all over the floor hiding the water snakes still lurking. I yanked down the mattresses and the images of Neil and all my favourite bands were untouched and looked glorious in that surrounding muck. It felt like some kind of omen, something bigger than losing our home.

“The song of his I most embrace is something that sounds so hidden and tucked away. Music Arcade is as intimate as it gets. Like Neil couldn’t sleep, like it was a hell of a day… so he walked over to his home studio recorder and whispered this pup like he was writing it just as it was being harvested. Quiet enough to wonder at his own meaning and place in the world at that very moment. Quiet so as not to wake anyone else in the house. And that sensibility is housed in all his songs. Powerful enough to be that quiet and while under the pondered impossibility of our troubled world, still show us a way out, an endgame spin. His songs show us a way to make it through the day, but at the very same time, have enough care in them to not wake anyone else in the house who managed to find some sleep.”

49.

I Am A Child

(Live Rust, 1979)

Raw version of Young ache from the Springfield’s contractual Last Time Around. As selected by Dylan LeBlanc.

“I was asleep at night and I had Live Rust playing continuously. I had always skipped that song but on that occasion it played and I woke up as it was playing. It was a dark and dreary day but at that point that song seemed like the perfect song to wake up to. There is an innocence and youthfulness in it combined with a feeling of desperation. It’s like Neil trying to tell us something that we really can’t understand. That’s why it appeals to me, because I have felt that same sense of hopelessness so many times. (Sings) ‘I am a child/I’ll last a while/You can’t conceive/Of the pleasure in my smile.’ Neil’s telling us that people take children for granted, and the song is also a reminder that you are going to get hurt. Musically, the six chords in that song are beautiful. It moves so well. The music actually paints a picture even without the words. It feels like you’re being taken back to an older time rather than the time that you are in. I think Neil Young always wrote that way. That’s what makes him so timeless.”

48.

Ambulance Blues

(On The Beach, 1974)

Through the past, darkly, with burnouts, critics, Presidents and worse. As selected by Phosphorescent’s Matt Houck.

“It’s a monster, a really long and hypnotic and all-encompassing nine-minute mood piece that smoulders along. Loose, resigned and weary, but still full of piss and strength. It can change the entire mood of what’s going on around you, which is really impressive. And these little fragments of lyrics appear each time you hear it. I once wrote a song called Not A Heel that was directly inspired by the line, ‘I’m such a heel for making her feel so bad.’ That really struck me then as I was trying to convince myself that I wasn’t a heel, for the exact same reasons. The references – Richard Nixon, Charles Manson, Patty Hearst, CSN&Y – are quite specific but like all great art, it rises above whatever the artist is specifically talking about and becomes universal. Just listen for those nine minutes and then put the needle on it again. And listen for nine more. Listen to that wandering fiddle. Listen to that voice. And the ragged way it’s recorded. It’s all right there. You can just feel it.”

47.

Old King

(Harvest Moon, 1992)

Twanging C&W hymns man’s best friend: “I told the dog about everything.” As selected by Swans’ Michael Gira.

“When I think of Neil Young, this is the song that pops into my head: (sings) ‘My dog King wasn’t afraid to jump off the truck in high gear’ (laughs) and then it’s got the banjos. I think it’s wonderful coming from the same artist that wrote The Needle And The Damage Done. Harvest Moon has some beautiful love songs on it, but it takes a lot of talent to be able to write a song about a dog. It could be in a Disney movie. From the first couple of lines – Willie Nelson has this ability, too – you’ve got this picture of the whole world. To be able to do that – despite how comical the subject matter is – I think is a true talent.”

46.

Winterlong

(Decade, 1977)

Rock as melancholy and monumental as any in the canon. As selected by Pixies’ Black Francis.

“Beginning with the title, it is creative. It’s a new word. And we all know what it means, but it has more weight than ‘winter long’. The song begins in a sleepy but totally solid tempo on a one-bar ascending riff that announces the chord progression that follows it: C, Am, F, G. A perfect 1950s chord progression. The 1950s chord progression. The amps are just loud enough to break up a bit. The sound is warm and the guitars gurgle like liquid coming out of the ground. That’s how it sounds to me. Like liquid from inner earth. And my heart is breaking and I don’t even know why yet. The band plays one time through and resolves in an F and a C and the riff again before the spotlight blinks on Neil at the mike. ‘I waited for you Winterlong/You seem to be where I belong/It’s all illusion anyway…’ He longed all winter, but he also knows in the end it’s the trickery of the human perspective. Love is but it also isn’t.

“Second verse: ‘If things should ever turn out wrong/And all the love we have is gone/It won’t be easy on that day.’ I’m sorry. But that is heartbreaking. He knows it’s coming. And then we build toward that final chorus. ‘I waited for you Winterlong/You seem to be where I belong.’ Over and over. The pathos of the minor chord feeling is gone, and a knowledge and a resignation has replaced the sadness, almost triumphant. The singer has been formed by the experience. A mutation has occurred. He is stronger and more lonely, but he isn’t waiting any more. He will never have that feeling ever again. Ever. Forever.”

45.

Thrasher

(Rust Never Sleeps, 1979)

Or “Why I Quit CSN&Y”, charged with slippery symbolism. As selected by art critic and Neil nut Matthew Collings.

“I like the narrative. I like all that stuff about ‘crystal canyons’, about the drugs being taken by Crosby and Stills. And I like, ‘Brings back the time when I was eight or nine/I was watching my momma’s TV/It was that great Grand Canyon rescue episode.’ It’s a lovely leap, flashing up those images. But the song is also a warning: the thrasher is death. You will be cut down. That gives the song its epic feel, that and the structure: no chorus, just great long verses like Dylan’s Sad-Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands, heroic in a way that very few people have managed to pull off. If he were a visual artist I think he would have to be someone expressive. Sometimes when he’s playing the lead on the guitar, you feel like he just sort of leant on the guitar, just groaned the noise out. It’s the most sublime sound, like great buildings crashing, a big historical sweep. I think he’d be Mark Rothko – with those big banks of tone and colour.”

-

READ MORE: Bob Dylan’s 60 Greatest Songs: As picked by Paul McCartney, Patti Smith, Nick Cave, Bono and more!

44.

Here We Are In The Years

(Neil Young, 1968)

The hidden gem of Young’s fussy debut. Dig the horn-emulating synth! As selected by Midlake’s Eric Pulido.

“I somehow overlooked Neil Young’s debut album at first. But once I spent some time with it I found the ever-present beauty, most especially in this song. I was hooked by the concertoesque piano intro that then settles right into a simple yet perfect rhythm section. It just feels so good. And if that wasn’t enough, the delicately beautiful side of Neil’s voice over this bed of continued musical gold, with great acoustic and electric guitar flourishes throughout, makes it that much more impactful. The lyrics of a world divided into a ‘city vs country’ type mindset and the impending repercussions, is also something that I can relate to and is even present in some Midlake tunes. Thanks Neil, for another amazing tune.”

43.

It’s A Dream

(Prairie Wind, 2005)

Everyday country life transformed into exquisite reverie. As selected by Doug Paisley.

“I first heard It’s A Dream in Heart Of Gold, the concert film by Jonathan Demme. Initially, there was a part of me that resisted its plaintive tone: it just seemed too simple. By the time I heard the song again later in the film, I mostly knew how to sing it. When I was in a rough patch I cued up the song every morning to start my day. We played It’s A Dream on-stage at the Cameron House in Toronto a while ago and a number of people came up to me afterwards just to say that the song had made them cry. That had never happened to me before, but I knew it wasn’t my performance that had touched them so deeply. I grew up a few blocks from where Young had lived and gone to high school in uptown Toronto. His songs were often playing at neighbourhood parties as we drifted about in a teenage haze. There were other bands, Grateful Dead, Led Zeppelin, that people seemed to build up their whole identities around. With Neil Young’s songs there were no requisites for listening or identifying, it was pure music. That must be why they’ve gone so deeply into my consciousness and how they are living there still.”

42.

Sleeps With Angels

(Sleeps With Angels, 1994)

Burning out versus fading away. As selected by MOJO writer David Fricke.

As eulogies go, Sleeps With Angels, Neil Young’s instant memorial to Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain, was short, brutal and ambiguous – much like the life of the man he mourned. On April 8, 1994, Cobain was found dead from a self-inflicted shotgun wound at his Seattle home. In his rambling anguished suicide note, Cobain quoted Young, from Rust Never Sleeps’ My My, Hey Hey (Out Of The Blue): “It’s better to burn out than to fade away.” Two weeks later, on April 25, Young convened his loyal garage band Crazy Horse at Complex Studios in Los Angeles and recorded a 20-minute instrumental that sounded like Nirvana in leg irons, a funeral shuffle coated in ugly throbbing fuzz, with a stuttering riff and pie-plate-like cymbal clangs. Young cut that beast down to a three-minute splinter, adding barely whispered vocals – Young singing with himself via slightly skewed overdub – dotted with falsetto cries (“Too late! Too soon!”) that sound like rattled seraphim at the pearly gates, frantically double-checking the guest list.

Unlike Ohio, Young’s fast, outraged response to the 1970 Kent State University massacre, and Tonight’s The Night, his sayonara to roadie and OD victim Bruce Berry, Sleeps With Angels is all allusion, a reflection on the most desperate kind of comfort and the empty space left behind. But it is also painfully acute writing. The opening lines – “She wasn’t perfect/She had some trips of her own” – is a plain reference to Cobain’s widow, Courtney Love. What follows – “He wasn’t worried/At least he wasn’t alone” – is a revealing compassion. Even from a distance, Young could tell: Husband and wife had been perfectly, if fatally, suited to each other.

'We just wanted to hear all these Neil Young stories...'

Krist Novoselic

Young and Cobain never met. They came eerily close. In the spring of 1991, when Nirvana were hunting for a producer for Nevermind, the band approached Young’s producer David Briggs. Nothing came of it, although there was a memorable meeting over coffee at a Denny’s restaurant. “We just wanted to hear all these Neil Young stories,” bassist Krist Novoselic recalled. Nirvana nearly opened for Young on the ’91 Weld tour – Cobain’s buddies Sonic Youth, already on the bill, tried to get them the opening slot. And Young biographer Jimmy McDonough noted in Shakey that he saw Cobain and Love hanging around backstage at Young’s 1993 Harvest Moon show in Los Angeles.

Finally, in the first week of April, 1994, Young – troubled by the news of Cobain’s near-suicide in March, from a drug overdose in Rome – attempted through management channels to reach the younger man. Cobain never got the message. Sleeps With Angels, added at the last minute to Young’s next studio album, would be his penance. “It’s just too bad I didn’t get a shot,” Young lamented years later. “I might’ve been able to make things a little lighter for him.”

41.

Broken Arrow

(Buffalo Springfield Again, 1967)

Suite inspiration from Buffalo Springfield. As selected by MOJO writer Richie Unterberger.

Out-and-out psychedelia is not Neil Young’s stock in trade. Yet for a golden moment on Buffalo Springfield’s second album he married lyrical obscurity to arrangements as magically orchestral as any psychedelic rock this side of Sgt. Pepper. The six-minute Broken Arrow shifts mood and perspective like a movie of three discrete vignettes interrupted by haunting, sometimes surreally disturbing flashbacks. Its dedication to old friend (and, briefly, Springfield bassist) Ken Koblun notwithstanding, it defies easy interpretation and keeps listeners perpetually off-balance, the instrumental interludes quaking and shimmering as they dissolve into the three verses.

Those verses – the core of Broken Arrow – are impressive enough on their own, driven by one of Young’s grandest, most melancholic melodies and progressively lusher, soaring backdrops. The words deal with disillusionment – already a worn theme in rock, but here outlined with delicious dreaminess, whether Neil is alluding to the emptiness of pop stardom or JFK’s assassination, or both, or more, blurring that day in Dallas with imagery from a medieval parade. It’s all united by the yearning chorus, tying failed dreams to the broken arrow, used by Native Americans as a symbol of peace at the end of war.

An ideal prelude to the opening miasma of post-gig alienation...

Broken Arrow works beautifully enough as an unadorned folk song, as the November 1968 solo acoustic performance on Sugar Mountain: Live At Canterbury House would ultimately reveal. But it needs its wildly disparate instrumental sections to push it to the masterpiece level. The opening snippet of Mr. Soul – recorded in the studio and sung by Springfield drummer Dewey Martin, though overdubbed screams pass it off as a live concert snippet – is an ideal prelude to the opening miasma of post-gig alienation: where fans linger for a glimpse of their idols through the windows of a black limousine.

A merry-go-round turning into a nightmarish swirl of dissonance sets up the far more bizarre second verse, linked to the final, exponentially more ominous section with martial drums conjuring JFK’s funeral march. Odder still is the instrumental tag, a loungeish jazzy jam featuring session pianist Don Randi and clarinettist Jim Horn, ending with the spooky pulses of a beating heart.

At the time, some found Broken Arrow’s production too over-the-top, including, perhaps, other members of Buffalo Springfield. Martin and Stephen Stills later recalled learning the song on the hoof and Young confirmed in his notes to Decade that it took more than 100 takes to get right. Part of the song was airlifted from a Springfield outtake, Down Down Down, Neil admitting in Hit Parader soon afterward that,

“I had a two-minute song with no repetition, so I figured the only way to make it work would be to turn it into a six-minute song, repeat the refrain three different times and take it into three different movements.”

Forty-odd years on it continues to transcend its cut-and-paste origins, staking its claim as Young’s most glorious suite: a hypnotic, roller-coaster rush, a better movie than any of the actual movies he’s made.

40.

See The Sky About To Rain

(On The Beach, 1974)

Lyrical, self-healing bimble on wobbly Wurly piano. Probable “slow-drug” input. As selected by MGMT’s Andrew Van Wyngarden.

“This is the song I can listen to over and over the most. It’s the simplicity – the steel guitar and the soft drums – real loose but sparse. There’re two sides of the song, a kind of environmental issue, but it’s also Neil struggling to cope after the Tonight’s The Night tour, the ultimate ‘fuck you’ tour, hated by everyone. There’s that final verse: ‘I was down in Dixie Land / Played a silver fiddle / Played it loud and then the man / Broke it down the middle.’ The Neil albums I first got obsessed with were Harvest, After The Gold Rush and then Tonight’s The Night, the tequila one – but there’s something uniquely ominous about this.”

39.

Will To Love

(American Stars ’N Bars, 1977)

Haunting field recording unveils Neil at his most epically desolate. As selected by

Dinosaur Jr.’s J Mascis.

“I’ve got an older brother, and he had a lot of records, and that’s how I started listening to Neil’s stuff. I don’t remember anybody at the time not liking Neil Young, except for people who thought that he was a terrible guitar player and were into Eddie Van Halen or something. I was attracted to the sound of Neil’s guitar, the feelings he evokes. It can touch you somehow. It’s like Neil’s speaking to you through his guitar.

“Will To Love’s always been my favourite song. It’s really intimate, intense; you’re sitting by a campfire, you can hear the fire crackle… It’s really spacey; he sounds so depressed, like he’s detached, floating down the stream, just kind of floating away from reality and problems. The Dinosaur Jr song Not The Same [from 1993’s Where You Been?] was definitely inspired by trying to capture that feeling. It’s as close to a rip-off as I’ve come, I suppose.”

38.

Goin’ Back

(Comes A Time, 1978)

Shimmering strums usher in misty visions of Eden. As chosen by Rumer.

“I heard it for the first time recently, and it made me cry. The idea of wanting to go back to a place of innocence, but in that place ‘there’s nowhere to stay’ – that’s so powerful. The lyrics are strange, bleak, and they speak to me at exactly the point I’m at in my life. I’ve been such a hobo, all my life, like a stray dog, wandering about. I’ve been free, but I’m not free any more. The way Neil Young is, the way he writes, is just so intuitive, he just seems to follow his subconscious. Then there’s his voice – it’s so feminine, with that bit of sweetness to it, but he’s very much a masculine man, raggedy and almost punky. Among all those early ’70s singer-songwriters, he was the dark one, the dark star. At the same time, he’s like a little boy, forever yearning and searching, in the moment, a rolling stone, someone who is going to follow the muse no matter what. It’s what makes something like, say, A Man Needs A Maid so tragic. That feeling of desolation and loneliness, because he can’t reconcile a relationship with this overwhelming mission, his ministry. Neil’s way is bold and brave, but it’s lonely.”

37.

Transformer Man

(Trans, 1982)

Synth Neil’s underrated enigma. As selected by Devo’s Gerald Casale.

“Dean Stockwell and Toni Basil turned Neil onto Devo in ’77, and we ended up doing a scene in [Young’s panned movie] Human Highway. He was much more of an iconoclast than we ever could’ve imagined. I think he was genuinely turned on by synthesizer music. He was kind of a Dada joker, and we liked that aspect of him. But this song is very Devo. He’s talking about some new version of The Man. Like, the man who pulls the strings, the man who’s not on TV – not the song and dance man for marketing hope or something like that, but the guy that really makes things happen or not happen. [NB: the song is often said to be about Young’s problems in communicating with his younger son Ben, the second of his boys born with cerebral palsy]. As you get older, you get to know human nature, and how deals are really cut, how it isn’t like the good of the many that drives anybody to do anything. It’s pure brute exercise of power. Then at a certain point, it’s so much chaos, and such a big mess, that the system doesn’t work anymore. That’s the point that Western culture is at. It’s Devo!”

36.

F*!#in’ Up

(Ragged Glory, 1990)

Molten pain and guilt meets riff like Vulcan beating his anvil. As selected by Endless Boogie’s Top Dollar.

“Why do I keep fuckin’ up?!” Yeah, I can relate to that, those semi-conscious dynamics that lock me into patterns of self-sabotage are toxic for relationships. Lots of people say Neil’s songs speak to them in a personal way. F*!#in’ Up spoke to me. I was already jazzed that Neil was back in Crazy Horse hard-rocking action at the time, and then… BULLSEYE! F*!#in’ Up? Fuckin’ A! That revolving, heavy-hitter holding pattern riff explodes and implodes simultaneously, the perfect sonic version of fuckin’ up over and over again. You know you’re gonna do it, here’s the anthem. “Sorry, sorry!” he wails at the end of one live version. It hits me close, the price for intimacy is way high, fuckin’ up is an easier load, must have a heart of steel, and whoa… those ‘broken leashes on the floor’! Sometimes the song sounds celebratory to me in a twisted way, but that’s the guitars: lyrical fragments swirling in a maelstrom of stormy aggression. Try to find a live clip on YouTube where he isn’t tearing the notes out of Old Black at the same velocity and intensity that’s in his mind. When you can do that you can get away with fuckin’ up, forever.”

-

READ MORE: Neil Young And Crazy Horse Fu##in’ Up Review: Young and co. breathe new life into past glories

35.

Don’t Let It Bring You Down

(After The Gold Rush, 1970)

Death and doom abound but “you will come around”. Hmm, if you say so… As selected by John Grant.

“This always reminds me of my brother Dan and his love for Neil Young. The ‘dead man lying by the side of the road with the daylight in his eyes’ is an amazing, horrific, image, and for me this is one of those songs that provides such vivid snapshots of moments that the overall melancholy of the song serves not to bring you down but to lift you up. I always find myself thinking that I better stop taking things for granted – like my relationship with my brother, for example. I always think it’s about lack of perspective and that, even though we have no control over the goings-on in the world, we still have to think about today and carry on regardless. I have to say that I was never a big fan of Neil Young’s voice to begin with. But now it’s like a security blanket, and that blanket is handmade of the finest and sturdiest and softest material money can buy.”

34.

Don’t Be Denied

(Time Fades Away, 1973)

Anthem for the left-out and left-behind. Ye shall overcome! As selected by Wooden Shjips’ Ripley Johnson.

“As a kid I didn’t know anything about Neil’s biography, so I would glean as much as I could from the songs and the album photos. Don’t Be Denied seemed to be one of his most literal and autobiographical songs, and that’s part of its appeal to me. It’s a mini-biography of his early, pre-stardom life – ‘The punches came fast and hard / Lying on my back / In the school yard’ – and lays out many of the themes and values of his work. After hearing this one song you feel like you really know where he’s coming from. I had a chance to see a secret Crazy Horse show in San Francisco in the ’90s and they played Don’t Be Denied with the lost ‘Oh Canada’ verse. Since the album had been so neglected up to then, it was really special to experience that. Everyone in the audience could feel that the guy on-stage was still the same guy in the song, the guy who started a band and played all night, and that defined his life.”

33.

Revolution Blues

(On The Beach, 1974)

Like a feral Dylan drunk on hate surfing a superbadass groove. As selected by R.E.M.’s Peter Buck.

“Revolution Blues was such a totally ballsy move. To write that in the mid-’70s, when Charles Manson’s still the pariah of the scene, and here’s Neil taking this song that relates what Manson did to the movie and music business, conveying a lot of Neil’s ambivalent feelings about showbiz. I don’t think I could have done that. And it’s a great performance by the band, whoever that band is – I think it’s almost certainly Rick Danko on bass. I bought both Time Fades Away and On The Beach at the time they came out because they got really bad reviews. There was a local hippy paper in Atlanta, and the Time Fades Away record review was just the quintessential bullshit hippy review: ‘Neil’s the type of guy you used to be able to smoke a doob with your old lady, and then he makes this record which is all noisy. You need to get all mellow again, man.’ And I thought, I hate mellow, so this must be great, and I was right. R.E.M. played with Neil in 1998 at a Bridge School Benefit. He called up to ask what songs we were thinking of doing. And I said, Weelll, y’know, Motion Pictures, On The Beach, Revolution Blues, Ambulance Blues… He said, ‘Man, you’re going all the way down with that…’ We played Ambulance Blues with him in the end. He’s very precise. The tempo can’t vary. You know, it’s natural in rock’n’roll if you get excited about playing something you speed it up a little bit. But not Neil Young. He’ll stop you and go, ‘No – here’s the tempo. It doesn’t go any faster.’”

32.

Words (Between The Lines Of Age)

(Harvest, 1972)

Harvest’s closer. Scraggy but profound. As selected by Chip Taylor.

“When I was a kid I used to listen to country radio because I loved the pain you could hear in those songs. Neil Young has that same beautiful sadness in his music. When I did my version of Words I really wanted to feel that. I needed to learn the song properly before I could really sink into it. Lyrically, the first section makes me think of Neil Young looking out of his cabin window contemplating all the things that have happened down the years on the land he looks out on. The second part of the song deals with the issue of class from the point of view of a servant or a junkman. The question is really: How would you feel if you were me? In terms of the music, the time signature jolts in the instrumental sections, musically representing the transition between generations. The fact that they rub against each other so quickly reminds me that life is short, real short – you’ve got one chance so don’t fuck it up!”

31.

Rockin’ In The Free World

(Freedom, 1989)

Catchy, conflicted: Neil’s Born In The USA.

As selected by Dream Syndicate’s Steve Wynn.

“I think it was the one-two punch of Landing On Water and Life that finally put me over the edge. I mean, enough was enough. And then someone gave me a [bootleg] cassette of the songs from [unreleased album] Times Square and I remember hearing Eldorado and thinking, Hmmm… maybe it’s not all over. And then just a few months later I saw Neil on Saturday Night Live. He was playing Rockin’ In The Free World and it was like hearing Cinnamon Girl for the first time. Maybe it’s like when you’re really hungry and get the first taste of something that resembles food. Sometimes the degree of hunger outweighs the quality of the meal. But it came at the right time, it felt like a bolt of lightning and it bought Neil and his fans another couple of decades together, so who knows? Maybe it’s his best song ever.”

30.

I Believe In You

(After The Gold Rush, 1970)

All emotion, no imagery, in one of Young’s most direct love – or not-love songs. As selected by Linda Ronstadt.

“It’s my favourite out of the Neil songs I’ve covered. It’s about the ambiguities in personal relationships. The conflict of you liking them better than they like you – or it’s the other way round and you want to cut your heart out. What’s that first line? (Sings) ‘Now that you found yourself losing your mind/Are you here again?’ You fall for somebody and it’s suddenly beyond your control, no safety net, your life isn’t your own any more. The ambiguity of romance was pretty new back then – the pill, people getting divorced – a new road map emotionally and culturally which Neil was exploring. On the road chicks were throwing themselves at the guys all the time. Such upheaval! With someone for a few hours, then you get on a plane, you arrive somewhere else – like a hammer shattered your reality. The passionate ambiguity, the howling need, it’s there in I Believe In You… that’s hard to capture in words. And maybe the title, the refrain, is a vote of confidence in a strong connection that might turn into a lifetime friendship. When I recorded it, it gave me the chance to really stretch out and bellow. It’s very operatic, a tenor might sing it. Neil has a very interesting voice in that context, really compelling, almost counter-tenor. Aaron Neville is the only American singer I’d compare him to, that beautiful, pure sound, a horn, an angel.”

29.

Mellow My Mind

(Tonight’s The Night, 1975)

Rustic fantasies ease Neil’s rock star stress. As selected by Simply Red’s Mick Hucknall.

“I discovered the Tonight’s The Night album when I was in art school, I would have been 19. I loved the fact that it was so rough and ready, but I’m sure the label was completely fucking horrified… I was particularly drawn to Mellow My Mind because he couldn’t hit the high note – the vulnerability of that. I even considered emulating it on the cover version I did [on 1998’s Blue LP], but decided that was a cop too far. I love the melody, and the wonderful imagery. There’s something Huckleberry Finn about the lyric – the ‘schoolboy on good time/Jugglin’ nickels and dimes’ – only Neil Young can write things like that. On the tour bus, we always have debates about who’s the king, who’s the daddy – Bob Dylan or Neil – and the band’s unanimous that it’s Neil. He’s a teller of home truths. He gives you direct wisdom: ‘You’re all just pissing in the wind.’ He never dresses things up.”

28.

For The Turnstiles

(On The Beach, 1974)

Banjos, enigma and, perhaps, a prophecy? As selected by Fionn Regan.

“Neil Young is a sapphire in a deep well, a strange bird in a storm, a lantern in a black night. Picking just one song is a challenge, but For The Turnstiles weighs in both melodically and lyrically. When the first note kicks off it feels like a door has just swung open for you to stumble into a dingy tavern, sea salt hanging in the air, a foot thumping on a pallet, a banjo hammering. Like all great Neil Young lyrics, these are as emotionally direct as they are enigmatic. Listening now, when Neil sings, ‘All the great explorers/Are now in granite laid/Under sheets for the great unveiling/At the big parade,’ it could be a premonition of the musical climate which has since emerged.”

27.

Cowgirl In The Sand

(4 Way Street, 1971)

…Nowhere’s electric megajam becomes a slice of CSN&Y-serving acoustic serendipity. As selected by Smoke Fairies’ Katherine Blamire.

“When we were growing up Jessica [Davies]’s mum had a great collection of mostly ’70s vinyls and we used to listen to them constantly. One of those records was the Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young live album 4 Way Street and that’s the first time we heard Cowgirl. When Neil Young takes the stage, the album really kicks off to another level, and the performance of this song is transporting, it makes you wish you were there. It’s lyrically pretty ambiguous – ‘Old enough now to change your name/When so many love you is it the same?’ It’s just the trace of a story you’re not allowed to entirely understand. Growing up in West Sussex, Cowgirl In The Sand inspired us to buy cowboy hats and wear them into town, where we used to go to shop and busk. We got massively heckled. I guess sometimes it’s best not to take the lyrics of a Neil Young song too literally.”

26.

Sugar Mountain

(single, 1968)

Childhood idyll remembered with regret. As selected by Ray Lamontagne.

“Every time I hear this song, everything gets painted in these autumn colours, and it takes me back to when I was seven. This guy named Red Randall had a ranch in Tennessee, and I lived in a bunk-house with my mom and my four sisters. My uncle lived in a Dodge Power Wagon nearby. My father was a musician in various bar bands, and at that time he was coming and going, mostly going, but I remember boxes of his old records around, and my uncle was always playing them. The beautiful melancholy of that melody, that other-worldly voice Neil had, really got to me, even then. Now, of course, listening to it, I can hear that it’s a song about losing innocence, that realisation that you have to leave the known and enter into the unknown. It’s a deep tune. And Neil was only 19 when he wrote it… Crazy.”

25.

Pocahontas

(Rust Never Sleeps, 1979)

Native America, and what we built on it. As selected by Kelley Stoltz.

“Neil is the gateway drug to anyone learning the guitar. Most songs of his are D to G and minor chords, simple progressions but they’re profound, beautiful songs. I love the acoustic songs on Rust Never Sleeps. I used to want Thrasher to be played at my funeral, but perhaps it’s a bit morose (laughs). Pocahontas’s opening line is so cool: ‘Aurora borealis, the icy sky at night/Paddles cut the water in a long and hurried flight,’ because you can really see those Indian dudes in their canoes. Neil often talks about how things were before every stone was turned, and how the more naïve, innocent way of life was disrupted. Pocahontos was written around the time of the oil crisis, and the emergence of global awareness of what man was doing. It’s one of the few of Neil’s songs I’ve done live, on piano, with a G Harmonica. That’s another thing; when you add harmonica, you can sound like Neil pretty quick. It’s the same way punk rock works; play a few chords up the neck, and you have the Ramones.”

24.

Harvest Moon

(Harvest Moon, 1992)

Neil reconvenes the Harvest team, 20 years on, makes sweet love to the missus. As selected by Stephanie Dosen.

“It instantly evokes the moment. You’re in the back field, it’s getting dark, and immediately you’re dancing. It has that slow, molasses feel, you can feel the warmth of a summer night. Even after all these years, whenever I play Harvest Moon, it’s like the moment I’m playing it in becomes more important. That skippy guitar thing is so simple but totally alien. You’ve never heard anything like that on the radio with all that pop music trying so hard to impress; it’s so sweet and sad and slow and reflective. The lyrics are beautiful, too: (sings) ‘Because I’m still in love with you/I want to see you dance again.’ When the harvest moon appears, it means it’s time to pull in the crops, and that’s what Neil’s doing on that whole record. It’s like things have gone full circle from the Harvest album, when he sowed these seeds, and now it’s time to take stock of what he’s got before the freeze sets in.”

23.

Philadelphia

(Philadelphia OST, 1993)

A psalm to love and lost. As selected by MOJO writer Bill DeMain.

Call it a stealth power ballad. Philadelphia delivers its profound emotional wallop without any histrionics or obvious button-pushing pop devices. Shuffling a delicate haiku-like melody through alternating vocal and instrumental verses, it draws you into its still centre, where Young’s trembling voice pleads softly for love and acceptance. The accompaniment is sparse – piano and muted strings. The lyric is both vague and vast. Folded inside couplets such as “Sometimes I think that I know what love is all about/And when I see the light I know I’ll be all right” are invitations for us to add our own images and memories.

This open-ended quality made the song a perfect foil for the final scene in Jonathan Demme’s movie, Philadelphia, as family and friends gather to eulogise Tom Hanks’ character, who has died from AIDS. When Young heard that there wasn’t a dry eye in the house as the credits rolled at the film’s premiere, his sly comment was, “It must’ve been quite an emotional release. Probably the only thing I could’ve done to surpass that is Wayne’s World 2.” Demme was more straightforward: “It was the perfect way to send people home.”

'[Originally] I wanted the movie to start with a giant Neil Young guitar anthem to relax all the homophobic guys in the audience.'

Director Jonathan Demme

Originally, the director had requested a very different kind of tune. “I wanted the movie to start with a giant Neil Young guitar anthem to relax all the homophobic guys in the audience, who would go, ‘OK, Neil Young is on board, I’m open now.’ We cut the opening sequence to Southern Man. I was hoping to have Neil maybe compose the Southern Man of homophobia. So this tape arrived and my wife and I listened to it and it was this very unanthemic, exquisitely written song, and we were sitting there crying, and I thought, ‘We’re going to end this movie on this note.’”

Never one to recycle himself, Young had followed his muse towards a ghostly hymn. “I knew it wasn’t going to come easy,” he confessed. “To tell you the truth, the song’s actually quite a bit over my head in terms of playing. It’s hard to play, and it’s got to be played loose.”

Harmonically, it draws its Satie-meets-Bacharach richness from Major 6ths and 7ths, those split personality chords that straddle the line between happy and sad. Young stirs the emotional waters further by shifting the key of his instrumental verses up a step, which subtly insinuates that the “brotherly love” he sings of will forever remain out of reach. Difficult as it may have been for Young to play, he performed a stunning solo piano version at the 1994 Academy Awards, where it was up for Best Song. In an ironic twist, he lost the trophy to Bruce Springsteen’s Streets Of Philadelphia, the beatbox-driven anthem that opened the movie.

In the years since, Young has collaborated with Demme on two concert films, including 2006’s luminous Heart Of Gold, but has rarely reprised Philadelphia, content to leave it as both a hidden jewel in his catalogue (royalties going to the Gay Men’s Health Crisis Center), and maybe the most moving one-off film song ever.

22.

On The Beach

(On The Beach, 1974)

Fame sucks. I’m stoned. Fuck you anyway. As selected by The Cardigans’ Nina Persson.

“When I first heard this around 1997, I already loved Harvest, but I didn’t like the Crazy Horse stuff. This was something else: a third aspect of Neil that was bluesy and dark and insanely slow. Lots of songs deal with that ‘it’s lonely at the top’ thing, but most of them piss you off because someone successful is complaining. This one doesn’t. It’s bigger and more clever than that. I identified with it because I’ve always been mixed up about fame. In The Cardigans I wanted to be a team player, but I felt lonely, always having to do press by myself because that was what the press wanted. The whole lyric is so strong and so true, but the first time I heard Neil sing: ‘I went to the radio interview/But I ended up alone at the microphone,’ I just wept. He’s great at making you think without using complicated language. When you’re making a pop album you’re told every second is precious, but On The Beach just goes its own way at its own speed.”

21.

Tired Eyes

(Tonight’s The Night, 1975)

The true tale of a Topanga Canyon drug deal gone bad. As selected by The Hold Steady’s Craig Finn.

“It’s the idealism being fried out of someone, like rock’n’roll had reached this tipping point and gotten into violence and crime, something really scary. It’s really dark and really sad. And adult: it’s someone who’s lived and been hurt and is trying to deal with something that’s beyond him – the deaths of close friends to drugs. A really sad and confusing thing for anyone to go through. How amazing that he tried to get through it by playing music.”

20.

A Man Needs A Maid

(Live At Massey Hall 1971, 2007)

’Cos man cannot live on honey slides alone. As selected by Danny & The Champions Of The World’s Danny Wilson.

“I remember very clearly the feeling I had when listening to Harvest the day after my exams were finished – one of the very few times I’ve felt completely free. But A Man Needs A Maid is so lonely and isolated and dark, something I would probably shy away from in my own work. I love the words – ‘the beggar goes from door to door’ – and though I’ve heard people discussing whether it’s a sexist song, I don’t see that. I see someone who’s lonely, someone who wants to shut themselves away entirely. We did our own cover in a night, me and Romeo [Stodart] from Magic Numbers and a guy called Rich Causon on keys. I’m very proud of it. It has some of the same loneliness but not the menace that’s in the Neil version on Harvest. Ultimately, though, I think the Massey Hall version is the version. That’s out there. Stripped of the orchestra the words are simply impossible to ignore.”

19.

Hey Hey, My My (Into The Black)

(Rust Never Sleeps, 1979)

Neil takes up punk’s gauntlet: “Is this the story of Johnny Rotten?” As selected by Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore.

“That song made my heart stop in a really big way. I first heard it walking down Canal St in NYC in 1979, coming out of a little radio speaker on the street, and the real molten, overamped guitar stopped me in my tracks. When I found that it was the new Neil Young record, I couldn’t believe it. I’d boxed a lot of pre-’76 music away. It was eradicated. But hearing Neil play Hey Hey My My for the first time reawakened for me the wonders of pre-punk music. That song inspired me to radicalise the guitar within songwriting. I saw him recently. He was playing Le Noise before it came out, sort of testing it. I went with a friend of mine named Bill Nace, an experimental guitarist who uses metal files and wooden sticks to create guitar music. I introduced him to Neil, said ‘This is Bill, he plays file guitar.’ And Neil’s like, ‘What’s that, file guitar?’ We explained, and Neil’s eyes just got real big, and then his people had to pull him away. I’ve been trying to figure out how to get a recording session with Neil where we just use files and sticks on our guitars, and just do experimental guitar stuff. That’s a dream of mine. He’s a busy man (laughs) but I have put word out.”

18.

Old Man

(Harvest, 1972)

The rock aristocracy’s favourite Neil Young song! As selected by David Crosby*.

“Songs have to make you feel something in order to be good art and when I listen to that song, I think Neil still – when he sings it – feels the emotions that he felt about this old guy that was livin’ on his ranch and the similarity of their lives, the connection between ‘em. I liked it that he could see into the guy’s life and that he could see into his own life and he could see the similarities. He could put himself in his place. Neil’s a very good observer of other human beings. He’s not one for admitting that his age is passed or that he’s as old as he is. He wants to be out there on the front edge of creativity. He doesn’t like singing old songs or songs that show that a lot of time has passed for him. But I think Old Man is beautiful. Really beautiful and really insightful. One of the ones I loved singing with him the most.”

*Speaking to MOJO in 2011.

17.

Expecting To Fly

(Buffalo Springfield Again, 1967)

Or “Why I’m Leaving Buffalo Springfield,” wrapped in symphonic glory. As chosen by Dungen’s Reine Fiske.

“It’s a song that hits you straight away, because of the incredible Jack Nitzsche string arrangement that opens it up with this sun-drenched sound. It’s the ultimate bittersweet song, a song about him leaving the band, or a song for anyone who needs help letting go. The end of the song is beautifully cinematic. You can almost see someone, or yourself, going up into the sky. And, that’s the end of this amazing film. As a guitar player it’s pretty hard not to be struck by the guitar playing. You sense the actual condition he was in when he recorded things. The guitar can sound grumpy, or desperate. He is a very delicate player, but sometimes he just belts, and his sense of melody and timing is always amazing.”

16.

Tell Me Why

(After The Gold Rush, 1970)

“Is it hard to make arrangements with yourself?” We’ve all been there. As chosen by Neil’s six string sideman Nils Lofgren.

“To me, Tell Me Why is a metaphor for transition, between where you are and where you’re going. The tune’s wonderful, and Neil has this kind of stark, whimsical matter-of-fact voice. This was my first real session work, 18 and scared, so there’s a lot of uncertainty here, but hope too. Neil asked if I’d play acoustic guitar. He said, ‘We’ll sit across from each other, I might even have you sing live harmonies,’ so I did. But I didn’t have an acoustic guitar, so he handed me this beat-up D18 Martin, the one on the album sleeve. [Producer] David Briggs said Neil had been writing a lot on it, so it had a lot of mojo. I did a little finger-picking inside the licks, all pretty quickly, and we started tracking. The next day, Danny [Whitten], Ralphie [Molina] and Neil and I sang additional harmonies and that was it. There are no guarantees in life but I’m glad it went well. And Neil gave me his D18 Martin at the end of the session, which blew me away. I still use it today.”

17.

Southern Man

(After The Gold Rush, 1970)

Corrosive anti-Jim Crow blast. As selected by Villagers’ Conor O’Brien.

“Southern Man is the knife right in the middle of After The Gold Rush that cuts you really deeply. There’s something amazing about the production, the drum sound, the way his voice is, the way he uses the backing vocals – it’s like an army of men, and he’s in the middle, screaming. What makes Neil great is, he doesn’t seem to cross anything out. He just pukes onto a page, and that’s the song. And even if some of it is childish or sloppy, it’s all the more endearing for that. It’s not too studied or academic, it’s just getting right to the core. And Jesus Christ, the energy…”

14.

Cortez The Killer

(Zuma, 1975)

The Aztecs meet angel dust. As selected by MOJO writer Keith Cameron.

Stoned to its mainframe, Cortez The Killer is the ’70s hippy experience in toto: the rapture and the rot, the love and the loneliness. Neil Young in spring 1975 was stepping off a treadmill of trauma that began in 1972 with the death of Danny Whitten, then dived through the ‘Ditch’ album trilogy and a bitter CSN&Y reunion, culminating in the collapse of his relationship with Carrie Snodgress, mother of his son Zeke. He had much to reflect upon, and Cortez became its parent album’s totem, because for all its historical derivation, it feels deeply personal.

-

READ MORE: Neil Young And Crazy Horse Live Reviewed: Rock’s greatest brotherhood make a blistering return.

We hear of a man who “came dancing across the water, with his galleons and guns/Looking for a new world, and that palace in the sun”, and obviously this is far more about Neil Young, the questing Canadian troubadour-turned-millionaire, than a 16th century Spanish conquistador and his Aztec counterpart (“with his coca leaves and pearls”). The Malibu home of producer David Briggs was a scene of depravity – drugs and girls were ever-present, dudes of varying depths of shadiness would wander by (one day Bob Dylan parked his car outside and just sat, listening) – with Young its epicentre, wielding power without responsibility (“And his subjects gathered ’round him…”).

A hallmark Young/Crazy Horse epic...

At seven and a half minutes, Cortez is a hallmark Young/Crazy Horse epic, configured around tension and release, and, of course, Young’s solos. The playing is ghostly and tentative, because this is the newly configured Horse, with the void left by Danny Whitten finally filled by Frank ‘Poncho’ Sampedro, a proper hippy who carried a gun, did drugs for breakfast, and now found himself shadowing Neil Young, at that point entering a period of such luminosity on the electric guitar it would define him for ever more.

On Cortez, the ensemble’s sensitive performance is remarkable, because the participants were off their collective nut. According to his accounts in Jimmy McDonough’s Shakey, the bonkers Sampedro, whose drug du jour was heroin, had “conned” bassist Billy Talbot into smoking angel dust with him as they recorded Cortez. So that’s how they sound so relaxed. “I thought the second chord was the first chord,” said Sampedro, who was nodding out as they played. “It’s only three chords.” The finished cut was pieced together by Briggs, a considerable feat given that the power to the console failed during the take, and by the time it came back a whole verse had been lost. When told, Young stated: “I never liked that verse anyway.”

This, along with the lyric’s dubious historical accuracy – Young later claimed they were written as high school homework – and the fact of its vocal not arriving until 3’22”, confirms that Cortez is all about the journey… and what gets left behind. When Young switches from third- to first-person (“I still can’t remember when, or how I lost my way”), the penny finally drops. The Horse are bombed, Neil is flying; the rest of us follow, seduced. It’s brilliant, but barely there.

13.

Ohio

(Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young single, 1970, compiled on Decade, 1977)

Neil’s requiem for Kent State. As selected by Pretenders leader, and survivor, Chrissie Hynde.

“I don’t claim to cast light on why it happened. But I was there. I was 19, studying art. Jeff Miller, who was shot dead, was in my circle of friends. Obviously, we were in shock. Then Neil Young comes out with that song and there’s understanding and an acknowledgement. Kent State University is 10 miles from my hometown, Akron. It was straight left-wing. Vietnam had polarised the nation. Then [Thursday, April 30, 1970] Nixon announced the invasion of Cambodia. The next night everyone gathered in town. We drank beer and dropped acid and wheeled these garbage cans into the street and set them on fire. An impromptu demonstration.

“On the Saturday we all went up to the campus and we burnt down this ROTC [Reserve Officer Training Corps] building. The National Guard had arrived and they threw tear gas at us. So we ran away. I was in the stampede and somebody near me yelled, ‘Walk!’ I did and, ever since, I’ve thought it’s a metaphor in life; when there’s trouble someone has to yell, ‘Walk!’

'I heard shots and people screaming...'

Chrissie Hyde

“Sunday was quiet. Monday was half-term and I was taking my portfolio to the art building – walking with Jeff’s girlfriend, in fact. You had to go through the Commons where the ROTC building had been. Another protest was going on and the National Guard had surrounded it – the four inches of charcoal that remained. Kids with rifles, some of them in the shooting position. Kids like us except their parents couldn’t afford to send them to university. A lot of students threw rocks at them.

“Then it got confusing. I heard shots, maybe 12 [official count: 67] and people screaming ‘They’ve killed them!’ I sat down right where I was and refused to move. I didn’t see anything more until some soldiers carried me away. By then, they had killed four students and wounded nine. The campus was closed down and there were crowds of us on the highway hitching, trying to get home.

“I knew Jeff was a big fan of CSN&Y, so the song meant a lot. It rocks, it’s melodic and it means something. It had a great hook: ‘Four dead in Ohio…’ That stands on its own. Expressed what we couldn’t express. Even now. We needed someone like Neil to give us a voice. Songs like this can instruct you, give you ideas… just make you feel you’re not alone, that more than anything. Ohio was a comfort for everyone caught up in the Kent State shootings.

“Music was my life. People like The Beatles, Hendrix, they gave you license to explore something else, more mystical maybe, that higher consciousness. Adults didn’t know what they were talking about because they weren’t on acid. But it worked for me, I never turned back. You were on a mission, you didn’t want to think it all meant nothing. Hippy ideology wasn’t just a fashion to me; I fucking believed it and I still do.

“I’d been falling in love with Neil Young from the genius solo albums and Helpless. Later I met him and I did say, “Thanks for writing Ohio.” He’s a really gracious, humorous person. And obviously one of the gods.”

12.

Powderfinger

(Rust Never Sleeps, 1979)

Ringing riff, sky-scraping solo, the Horse’s most fetching “ooh”s. What’s not to like? As selected by Band Of Horses’ Ben Bridwell.

“Powderfinger isn’t just one of my favourite Neil songs, it’s one of the best songs ever recorded. How did someone else not pick this before me? The story being told often catches me off guard like I’ve never heard it before, even though I’ve heard it countless times. The lyrics seem so personal and at the same time distant. Just when you think you know what the plot is, you can hear the words differently and re-imagine the story line. Like, “Red means run, son, numbers add up to nothing.” It’s funny to sing along with conviction and realise you have no idea what the meaning is. Hillbilly soap opera? Civil War drama? I don’t need to know.”

11.

Tonight’s The Night

(Tonight’s The Night, 1975)

Tears in your tequila, and spook in your heart as Neil seizes the day. As selected by Joe Henry.

“I knew who he was, of course: my older brother owned a copy of Déjà Vu. But the hippies-as-desperados stance failed to work on me, thus I never allowed myself to be seduced by Neil Young until he’d slipped the yoke of shimmering, smooth harmonies and left real blood on the tracks. Tonight’s The Night changed my mind, Neil crooning like a prison escapee calling on the glow of the moon for assistance while trying not to wake his cellmate: “Tonight’s the night… Tonight’s the ni-hi-hi-hi-ight…“ The night for what? To break free or die, that’s what. Neil is confronting what it means to live and create, to hold a small flickering flame in the fierce headwind of death’s inevitability.

“Neil was only 28 when he wrote and recorded this, his voice speaking with the craggy defiance of a man already grown old; but when he mourns his friend with the shaky voice – the spark in his eyes and his life in his hands – who does it sound like he’s describing? Whom is he really mourning? Well, you don’t need me to tell you. But therein lay his true liberation: because in embracing his own mortality, Neil Young is free of it. It’s a gift and a generous one, to shine a light back for the rest of us from up along such a dark and spooky road.”

10.

Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere

(Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, 1969)

Here comes the bummer. And yet, jauntily. As selected by Roy Harper.

“I first heard this track in a flat in Chelsea when one of The Who’s road crew brought in a copy of the album. He was raving about it and as soon as he put it on I thought, This is a great record. I knew that Buffalo Springfield were a good band but I didn’t really take Neil Young too seriously up until that point, but after hearing this I saw him as an individual. It didn’t matter whether he joined Crosby, Stills And Nash – which he did, of course – because this music marked him out as a genuine solo artist. The song itself is plaintive. It cries out in the way that Neil Young does, like a voice in the wilderness. It’s full of an emotion that was prevalent among all of us at the time: it’s a leaving song and we all wanted to leave behind the mess that faced us. We all wanted to clamber onto those wooden ships and escape, knowing that the state was coming and its power was getting bigger. It’s personal on one level, but more than that: it suggested that the things we were enjoying weren’t going to last. When I hear it now, it takes me back to that flat in Chelsea. It’s a dim and distant memory of a time when the world could be righted.”

9.

The Needle And The Damage Done

(Harvest, 1972)

Gorgeously picked elegy to Danny Whitten’s dissipating talent, and more. As selected by Gang Of Four’s Jon King.

“It’s the quintessential Neil Young. He’s the guy in the plaid shirt drinking in some anonymous bar, telling the story of a friend, maybe secretly himself, in that very honest and unironic way. There’s been so much cleverness, postmodernism in lyric writing, as if we’re all in an elaborate gag about culture. Neil Young is the antidote to that. Here he’s talking about the cost of hard drugs, the way it destroys your talent and worse, but in a way where you could be overhearing a conversation on the subway. He’s got that fragile sort of Smokey Robinson voice, like he’s still trying to grapple with the situation. You sense he’s very on the edge. And then it’s funny the way the song doesn’t really resolve itself. ‘But every junkie’s like a setting sun…’ And? It’s like he’s run out of things to say, because there are no more things to say. When people I know have died from overdoses – I think of [sometime Gang Of Four bassist] Buster Jones and Malcolm [Owen] of The Ruts – you get angry with them. It seems so aimless. It’s trite to say it’s a waste but it is a waste, and there is no full stop to the sentence.”

8.

Mr. Soul

(Buffalo Springfield Again, 1967)

Satisfaction fed through Neil’s mincer: “You’re strange, but don’t change.” As selected by Rush’s Geddy Lee.

“When we were growing up in Toronto, we were all big Buffalo Springfield fans, and Neil Young was one of our first heroes. We used to play Mr. Soul when we were a struggling bar band. We were trying to play our own material, but you couldn’t get work unless you played cover songs. So we tried to find cover songs that were not so obvious, not Top 40 songs. We were pretty crude and pretty loud, and so is Mr. Soul, so it would go over pretty well with our crowd. Neil Young is someone I really respect. We met in 1985 when a bunch of Canadian artists got together to record a single to raise money for African famine charities [under the name Northern Lights]. We did a song called Tears Are Not Enough that Bryan Adams wrote, and all these different singers each sang a line. David Foster was producing, and I remember watching another of my heroes, Joni Mitchell, sing her line. In my view, it was perfect the first time, but David made her sing it over and over. Then Neil Young sang his line, and Foster said, ‘Can you do it again? I think there’s a little bit out of pitch.’ But Neil said, ‘Hey man, that’s my style!’ And that was that. That really summed up Neil Young for me. The guy’s got big balls.”

7.

Down By The River

(Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, 1969)

Creeping, loping, groping: Neil and Crazy Horse find their groove. As selected by Crazy Horseman Billy Talbot.

“I don’t know how Down By The River evolved in Neil’s mind, but as far as the band is concerned, we went up to his house and he started playin’ and we started playin’ this song. A couple days later we came back and played it some more and that was that – we had it. The Rockets – the band Crazy Horse came from – were a jamming band in our own rehearsal room. We would play these two- or three-chord jams for an hour with Bobby Notkoff playing violin and George or Leon Whitsell or Danny Whitten taking solos. That’s what we did. Then we went in with Neil, and we naturally elongated his songs just the same way. But I really don’t think of these songs as individual things. I think of the total work of the man and what it represents. Some of these songs affected me at times differently. In the overall, I think it’s all of his work together that really is something to contemplate. It’s a big picture of one man’s view of his life on the planet: colossal, for one man to have accomplished in our time. Not somebody from history, but somebody who no doubt will be noted and be a part of history. That’s why it’s hard for me to think of him in terms of one song. They’re all good!”

6.

Helpless

(Déjà Vu, 1971)

Nature’s wonders knock him flat with awe. Yes, it’s “helpless” in a good way. As selected by k.d. lang.

“That song, it’s connective tissue to my Canadian musical DNA. ‘There is a town in North Ontario…’ [Young grew up in tiny Omemee, lang in tinier Consort, Alberta]. To me, Helpless is about looking back at your beginnings: ‘I still need a place to go/All my changes were there.’ He’d got into an emotional block, it seems, and that place, the physical beauty, set him free somehow. I can relate to that. ‘Blue windows behind the stars’: I’ve had my moments out on the prairie contemplating the universe. ‘The chains are locked/And ties across the door’ gives me the image of a summer cabin being locked up for winter. But it’s an emotional winter he’s talking about. And the chorus, ‘Helpless, helpless, helpless’, that’s pure, innocent awe of physical and spiritual beauty — not vulnerability, but the polar opposite: openness. Singing Neil’s music helps me discover who I am, my primordial natural self. He is the standard of truth and… rawness. I never asked Neil what he meant by Helpless. But when he had the aneurysm and I stood in for him at the 2005 Junos [Canadian music awards], I sang it and he called and left a sweet message on my voicemail…”

5.

Like A Hurricane

(Weld, 1991)

Force 12 assault on American Stars ’N Bars’ epic. Young’s axe apotheosis. As selected by Richard Hawley.

“I’d like to know more about him as a guitar player because that album, Weld, the guitar-playing on that is just immense. Forget the individual songs, his guitar playing has influenced me far more than his songwriting. When he plays guitar he doesn’t seem to have any formal time-limit. He goes beyond the form of the song and all of a sudden these wings appear out of his back and he just flies. It’s beautiful to watch. It seems to be a great release for him. I hear angels in it; all of a sudden a human being can fly, human flight is possible. There’s only him and Hendrix who you listen to and just go, ‘Fuckin’ ‘ell!’ My dad in the ’60s worked with Little Walter and he said that Walter would pick up any harmonica and any microphone and any amp and it didn’t matter. What got that sound was him. And I wonder how much of Neil Young’s sound as a guitarist is down to the equipment or down to him. He’s a force of nature.”

4.

Only Love Can Break Your Heart

(After The Gold Rush, 1970)

Joni Mitchell dumps Graham Nash. Neil rubs salt in the wound. As selected by Galaxie 500’s Dean Wareham.

“It’s one of his most beautiful and simplest ballads, easily in his top five! I first heard it in Michael Almereyda’s film Another Girl, Another Planet. It’s a dreamlike meditation on a string of romances that don’t work out, and that dreamy feeling is enhanced by the fact he made it in blurry monochrome Pixelvision. It’s like nothing is real and everyone is lost and to me Only Love Can Break Your Heart carries that message. It was a perfect moment of film and song working together. It’s what they call a ‘connecting lyric’ in that most human beings can relate to it. It describes the saddest truths about the human condition: that you fall in love with someone and end up being destroyed, or destroying someone. There aren’t many lyrics that can sum that up. The other thing I love is that it’s in three-four time, which balances the depressing message and makes the lyric feel uplifting. There’s just something about that time signature: because it’s missing one beat, it pulls you through to the next part of the song.”

3.

Heart Of Gold

(Harvest, 1972)

The monster hit in the canon. Raw as sushi, catchy as a lullaby. As selected by Sheryl Crow.

“I first heard the song in high school, when all the girls would embroider Neil Young’s or Bob Dylan’s names in their jeans. The first thing that struck me was the haunting, lonesome quality of Neil’s voice, and how it cuts right to your own emotions, especially when he’s singing his softer stuff. Lyrically, Neil has this cinematic simplicity that perfectly suits his vocal, and Heart Of Gold is super-poignant and articulate without wordiness or forced intellect – like, who else could get so much out of “And I’m getting old…”? Lyric and voice just flow as one musical emotion – he is like a tour de force of emotion. And that’s whether he’s being vulnerable and soft as on Heart Of Gold or Old Man, or sonic and menacingly intense like on Down By The River or Southern Man. Nobody has sounded remotely like him before or ever since.”

2.

Cinnamon Girl

(Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, 1969)

What you hear when someone says “the Crazy Horse sound”. As selected by Metallica’s Kirk Hammett.

“I can’t really remember the first time I heard Cinnamon Girl, but I imagine I was in my teens, riding in the back of a friend’s truck drinking Mickey’s Big Mouths. The second you hear it you’re drawn into the heavy rhythmic push and lean of the riff… kinda like hard rock but much more swampy and greasy. When the verse comes, Neil’s vocal with Danny Whitten has a lovely soft/heavy dynamic and when they go back into the main riff at 1:32 you can hear Neil turn his distortion pedal on – two seconds late! – to make the riff sound heavier. I love stuff like that.

“What’s cool about Neil is that he never hesitates to try whatever it takes to get his point across musically. Whether it’s just him on acoustic guitar, him solo on the piano, or with Crazy Horse, it seems that he will find the best way to play the song, whether it’s grungy or doo-wop… He always finds the best way to serve his music.”

1.

After The Gold Rush

(After The Gold Rush, 1970)

Alchemy, prophecy and ecology in one magical, timeless vision. As selected by MOJO writer Jim Irvin.

Neil Young’s enigmatic masterpiece is set in the past, present and future – the past: a medieval battlefield; the present: a basement where the narrator lies comatose; the future: a farewell gathering as refugees from a ruined Earth – The Chosen Ones – disappear into outer space. It is, according to Young himself, “an environmental song” declaring Mother Nature to be “on the run in the 1970s” and lyrically it’s unlike anything else he’s written. It is simultaneously broadbrushed and detailed, chilling and comforting, baffling and evocative, immediate and elusive.

It’s a work which raises many questions. For instance, Why that title, which isn’t referred to in the lyric? Does it concern Earth as an abandoned planet, its resources spent, like an exhausted mining town? Does it perhaps refer to the comedown from a particularly vivid trip? Or does it take a sly dig at Young’s recent sojourn as a suffix to Crosby, Stills And Nash for the disappointing, but lucrative, Déjà Vu album? Subconsciously, maybe; all those interpretations hold water. But the title originally belonged to a movie script written by actor Dean Stockwell. Young was so impressed by it he offered to direct and write the score, yet, even after the runaway success of Easy Rider, the hot young actor and his singing sidekick couldn’t convince any Hollywood squares to bankroll their peculiar vision and this song – which Stockwell thought perfectly captured the jump-cutting surrealism of his script – and one other, Cripple Creek Ferry, are all that remain of the project.

Young created it in a cramped studio he built at his Topanga Canyon home. Having tried recording the standard, company-approved way, he was keen to start cutting records using his own, more ad hoc methods. Eight of the album’s songs were recorded in this tiny space – with barely enough room for Young, his producer and one other musician, and no facilities for reverb or fancy effects. So it sounds small, dry and vulnerable.

Young plays the song on an upright piano in the key of D major, which, in the early months of 1970, when he was still only 24, put him in the register of a washed-up choirboy. After a 10-second intro, over the chords of D and G, the wavering voice enters with a slightly tentative delivery: “Well I dreamed I saw the knights in armour coming…” It’s all hopeful, major chords, D, G and A, until the words “fanfare blowing”, over a B minor introduce a shiver of unease.

It’s nothing short of miraculous for such a unique, complex and eternally resonant moment in pop music...

In verse two the narrator comes to in a burnt-out basement and lies there for some hours, from full moon to sun-up. He can hear music in his head (the B minor again) and he fancies getting high. When Dolly Parton covered the song with Emmylou Harris and Linda Ronstadt for their Trio II album, she called Young up to explain the song. He confided that each verse depended on what drug he’d taken at the time. Parton changed “and I felt like getting high” to “and I felt like I could cry.”

The only other colour on Young’s recording is a mournful horn solo after the second verse by Bill Peterson. It’s generally assumed that this uncredited performance is played on a French horn, but Peterson recalls it as the more trumpet-like flugelhorn.

For verse three we move into science fiction territory, the “chosen ones” are being readied to colonise space. Unlike the previous verses, where the final lines are repeated in full, “flying Mother Nature’s silver seed to a new home in the sun” is cut short the second time, the word “home” is held on an unresolving note while the piano fades. We are what’s left of mankind, watching our representatives, our own children maybe, sailing towards an unknown future. The hope and despair in that final “home” is almost unbearable.

Randy Newman has praised the song’s eloquent confusion: “I can’t stand that sort of ‘meadow rock’ thing – Neil’s doing it, and writing about a big issue in a simplistic way, but I still like it. I love it. There’s some kind of alchemy going on.” Strangely, contemporary reviews were rather snooty. Rolling Stone gave After The Gold Rush, the album, a resounding raspberry.

But it was huge seller. In 1975, the title song’s majesty was recognised more widely when a Dutch group, Prelude, had a major chart hit in the UK with a brief, haunting a cappella version. It has since been covered many times, by artists ranging from The King Singers to kd lang and its simple but supremely moving melody has inspired many instrumental versions from jazz piano to fretless bass and Irish fiddle.

Producer David Briggs claimed this glorious, time-travelling odyssey was conjured in about half-an-hour and recorded immediately. It seems unlikely, considering what initiated it (and Young’s conversation with Parton), but if that’s so, it’s nothing short of miraculous for such a unique, complex and eternally resonant moment in pop music.

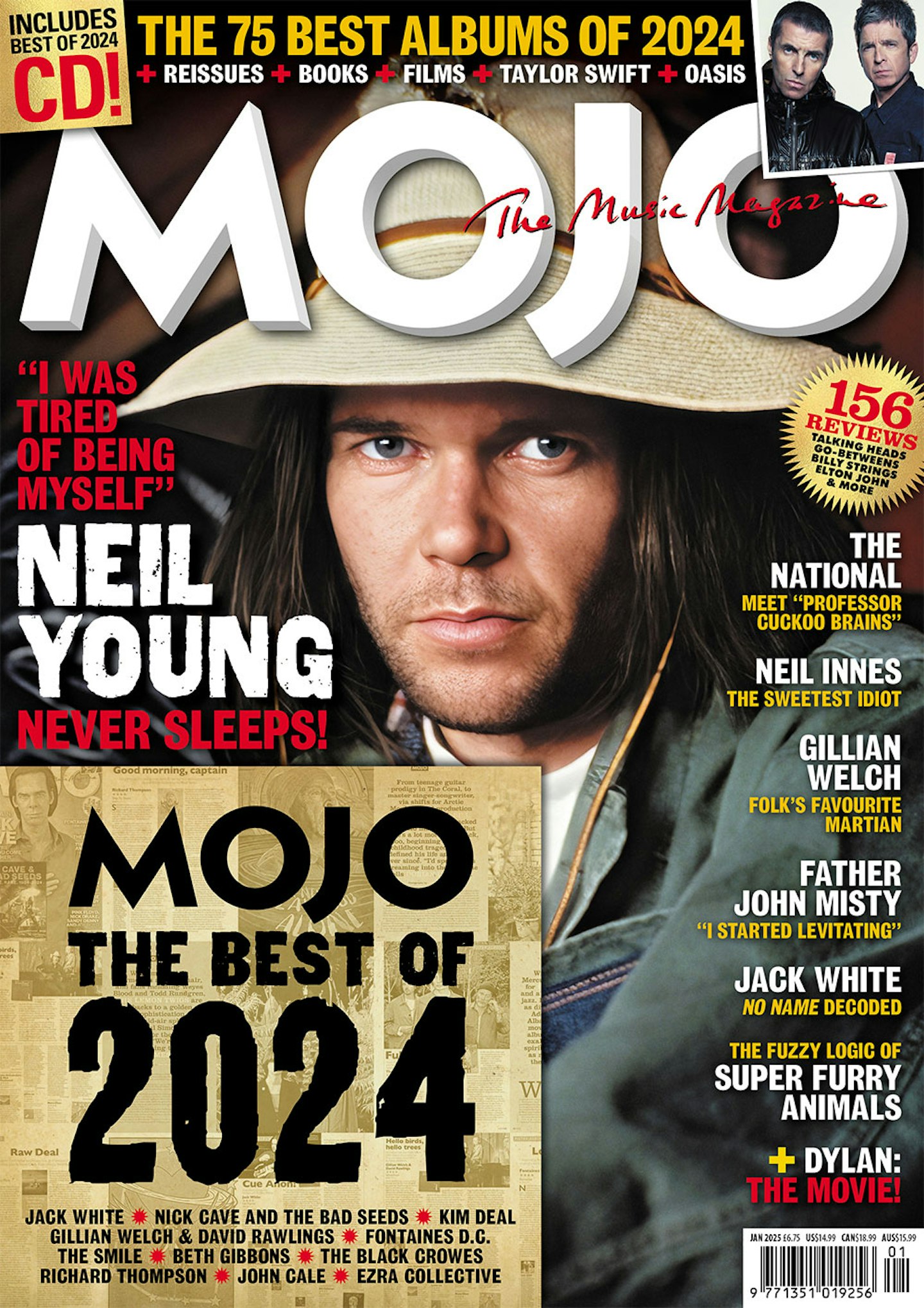

Neil Young on the cover of MOJO! From 1975 to 1979 – from Zuma to Live Rust – Neil Young hit a vein of form he’s rarely topped. Using the revelations of this year’s Archives III box set as a lodestar and insights from his collaborators, we plot his contrarian path. All that plus the best albums of 2024, Jack White, The National, Gillian Welch, Oasis, Taylor Swift and more, only in the latest issue of MOJO, on sale now! More info and to order a copy HERE!