Demystifying Jethro Tull’s magic formula in a 1978 interview, frontman Ian Anderson said: "Stylistically, I've always said that we can't be a heavy riff group because Led Zeppelin are the best in the world. We can't be a blues-influenced R&B rock’n’roll group because The Rolling Stones are the best in the world. We can't be a slightly sort of airy-fairy mystical sci-fi synthesizing abstract freak-out group because Pink Floyd are the best in the world. And so what's left? And that's what we've always done. We've filled the gap.”

-

READ MORE: Every Genesis Album Ranked!

Thin-skinned and curmudgeonly, Anderson rarely made being in one of the most successful bands of the 1970s seem like much of a joy, while his antagonistic relationship with the music press has not perhaps helped in securing Tull the kind of kudos legacy their massive record sales both sides of the Atlantic might have warranted.

Born in Dunfermline, Anderson ended up at grammar school in Blackpool, where he initially played in the Blades alongside future Tull members John Evan, Jeffrey Hammond and Barrie Barlow. However, the ex-art student made waves after he moved south to Luton, a line-up featuring guitarist Mick Abrahams, bassist Glenn Cornick and drummer Clive Bunker – and a name borrowed from the inventor of the seed drill – turning heads on the London blues scene.

A debut single miscredited to Jethro Toe augured ill, and Anderson arguably mastered marketing before he became a top songwriter, his trademark overcoat, one-legged flute playing stance and mad-eyed deadbeat look probably more arresting than Tull’s 1968 debut This Was. "The stage thing seems to be very important to the public and consequently it is a little worrying when people think I am an extreme 'randy', homosexual or drug addict,” Anderson complained at the time. “I'm not like that."

Indeed, in a loose, long-haired era, Anderson was positively ascetic. “I don't agree with people taking drugs or stimulants,” he told Record Mirror. “In fact I don't even drink.” Perhaps that’s why Cliff Richard outed himself as a fan, telling NME in 1969: “I think Jethro Tull are fantastic. I really do, they have so much talent.”

Cliff’s enthusiasm may have waned as Tull were gradually refashioned; Martin Barre replaced original guitarist Abrahams (but only after a pre-Black Sabbath Tony Iommi pulled out), and Tull experimented with a sort of homebrew psychedelia before hitting their commercial peak with 1971’s iconoclastic Aqualung and impish pseudo-concept album Thick As A Brick (1972).

From then on, things got sticky. With complicated tax arrangements and a brutal tour-album-tour schedule, Tull overreached themselves with 1973’s A Passion Play, failed to make a film to accompany 1974’s War Child, and didn’t regain their stylistic footing until the dawn of the punk era, with Anderson – by then living on a farm in Buckinghamshire – overseeing a thoughtful, rustic direction on Songs From The Wood and Heavy Horses.

Health issues, fluctuating lineups, 1980s keyboard sounds and Anderson’s focus on his much-mocked fish farms combined to reduce Tull’s cultural footprint in subsequent decades, but 21st century lineups continue to stake claim to their unusual little niche. “People see Jethro Tull as a kind of heavy metal folk band,” a bemused Anderson told Kerrang! In 1987. That and plenty more besides.

10.

The Zealot Gene

(Inside Out Music, 2022)

The idea of a Jethro Tull without guitarist Barre remains anathema to some – he and Anderson have not worked together for over a decade – but the band persist regardless. Now 77, Anderson is no longer standing on one leg to play the flute, but his urge to create remains, with The Zealot Gene – an Old Testament-flavoured broadside against populist politics and intolerance – abundant proof of artistic life. He rocks biblically on Mine Is The Kingdom and melds the personal and political on Where Did Saturday Go? and survivors’ guilt trip The Fisherman Of Ephesus. A grand metaphor for a life or intense dedication to a personal vision? You decide.

9.

A Passion Play

(Chrysalis, 1973)

Hubris struck as Tull followed up absurdist concept album Thick As A Brick with a barely comprehensible thematic tract about the recently deceased Ronnie Pilgrim’s journey into the afterlife. It was a No1 record in the US, but the band overreacted wildly to disappointing reviews at home, their management putting out a (false) story that Tull were retiring from touring in protest. Anderson has conceded since that A Passion Play has “too much stuff happening” and too many “bloody saxophones”, but even if it isn’t quite as smart as the band thought it was, it continues to enchant the kind of prog extremists that swoon for Pawn Hearts, Hatfield And The North and The Cardiacs. Skip the annoying fairytale; feel the mad fervour.

8.

Crest Of A Knave

(Chrysalis, 1987)

The band that recorded Tull’s 16th studio album featured three ex-members of Fairport Convention (Martin Allcock, Dave Pegg and Gerry Conway), but Crest Of A Knave nonetheless received an incongruous Grammy Award for best Hard Rock/Metal Performance, edging out youngsters Metallica and Jane’s Addiction. Imagine away the drum sound, and Steel Monkey is pleasingly feral, while Anderson’s flute is at its most lyrical on Jump Start. Sounds magazine complained of “the rank odour of Mark Knopfler” on the record’s thoughtful moments, but Tull’s awks encounter with a partially-clothed woman on the ten-minute Budapest finds a neat fusion of strutting cock rock and flaccid mid-life crisis.

7.

Heavy Horses

(Chrysalis, 1978)

With Anderson’s huskier voice heralding health issues, Tull marked the tenth anniversary of their debut with these songs about agriculture and obsolescence. The title track’s lament for the decline of British shire-horse power feels like a nod to the band’s position in a post-punk universe, while Journeyman quietly underlines the importance of hard unappreciated graft, and No Lullaby – a more psychotic take on Richard Thompson’s The End Of The Rainbow – warns of haters everywhere. Record Mirror’s reviewer cavilled about Anderson’s transformation from “the one-legged tramp in the filthy raincoat” to “the decadent lord of the manor”, but Heavy Horses shows off that new wardrobe with a grim dignity.

6.

War Child

(Chrysalis, 1974)

Chastened – a bit – by the response to 1973’s A Passion Play, Tull stripped away some clutter for their seventh LP. The initial project was a film (Leonard Rossiter was set to star, with John Cleese pencilled in as “humour consultant”), but with studios unconvinced, Anderson forged on with a high-gloss song selection, Dee Palmer’s Philly-soul-adjacent string arrangements helping to dispel any lingering prog stink. Instead, there’s Weimar sea shanty Queen And Country and the Steeleye spandex-ed The Third Hurrah, and if Tull misread the apocalyptic signs on Skating Away (global cooling is not a thing yet), they nonetheless anticipated mid-period XTC. Transitional, but on the way to somewhere good.

5.

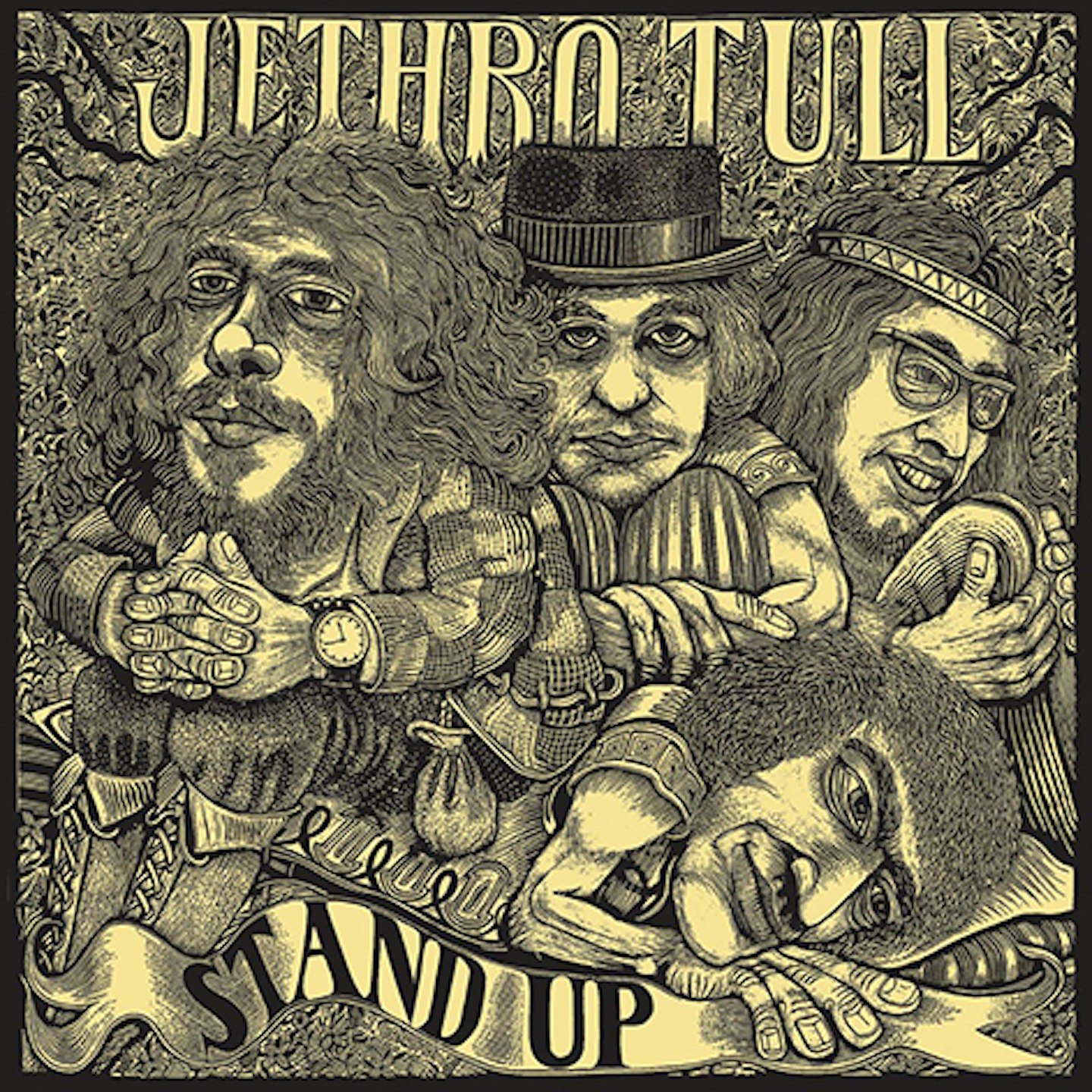

Stand Up

(Island, 1969)

The departure of guitarist Abrahams marked the yanking up of Tull’s blues roots, with their second album scratching for a new identity. Smoky, eclectic, Stand Up bears the faint scent of the Kentish Town bedsit where Anderson wrote the bulk of these eccentric songs, but the pop-up gatefold sleeve was a measure of a group with depth. With as many bongos as drums, Stand Up is a fairly ‘sit down’ affair but is also pretty in a way later Tull records aren’t; A New Day Yesterday, Jeffrey Goes To Leicester Square and For A Thousand Mothers meld Barre’s psychedelic guitar, Anderson’s flute and proto-prog time signatures, while live fave Bourrée finds the woodland glade sweet spot between Fairport Convention and Traffic.

4.

Minstrel In The Gallery

(Chrysalis, 1975)

“When anyone works with Ian, Ian dominates,” conceded Barre in 1979, but with a little more space to play with, Anderson’s most loyal lieutenant (lead guitarist from 1969-2011) made his presence felt reasonably forcefully on Tull’s deceptively heavy eighth LP. Less of a production than the preceding War Child, the title track sets the tone for an album of Tudorbethan acoustic songs which are periodically subject to intense metal bombardment (e.g. Cold Wind To Valhalla, Black Satin Dancer). Recording in Monte Carlo, the newly-divorced Anderson looks back to Blighty with a barbed ruefulness on the Baker St Muse suite; surrounded by ostentatious wealth, but longing – spiritually – for Blue Boar egg and chips.

3.

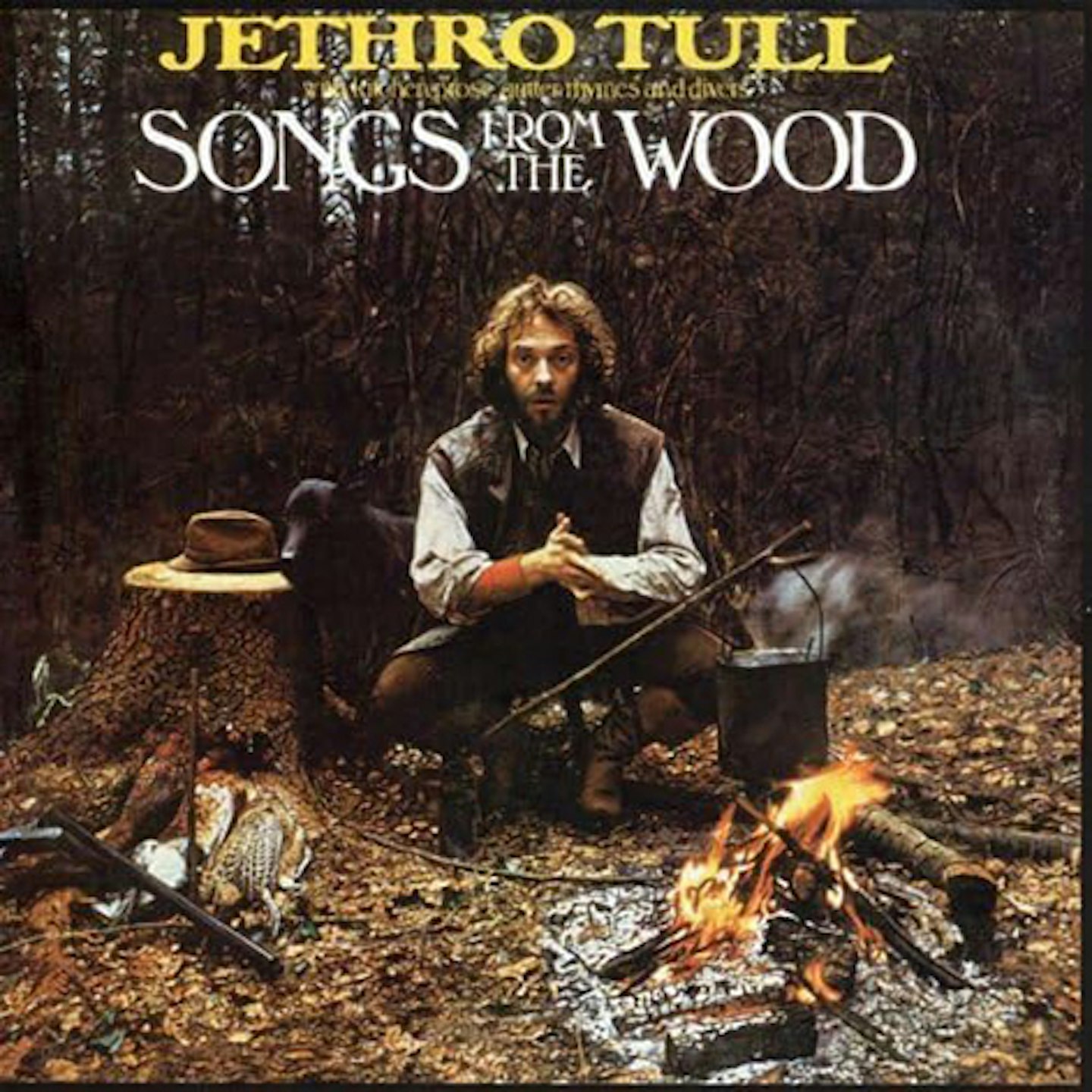

Songs From The Wood

(Chrysalis, 1977)

Anderson was never a folkie, but the band’s tenth album shares a similar rubber wellies and horse brasses sound world to Steeleye Span (who Anderson produced) with extra electronic splashes from keyboard wiz Palmer. “It is country rock, but in the British sense,” joked Anderson, who was newly remarried and settling into impending fatherhood on his farm as Tull enjoyed a blissful recording experience in London. The enthusiasm is infectious. “Join the chorus if you can, it'll make of you an honest man,” he sings on the title track, before giving in to simple pleasures on Cup Of Wonder, Velvet Green and Fire At Midnight. Tull’s most joyous album by a country mile.

2.

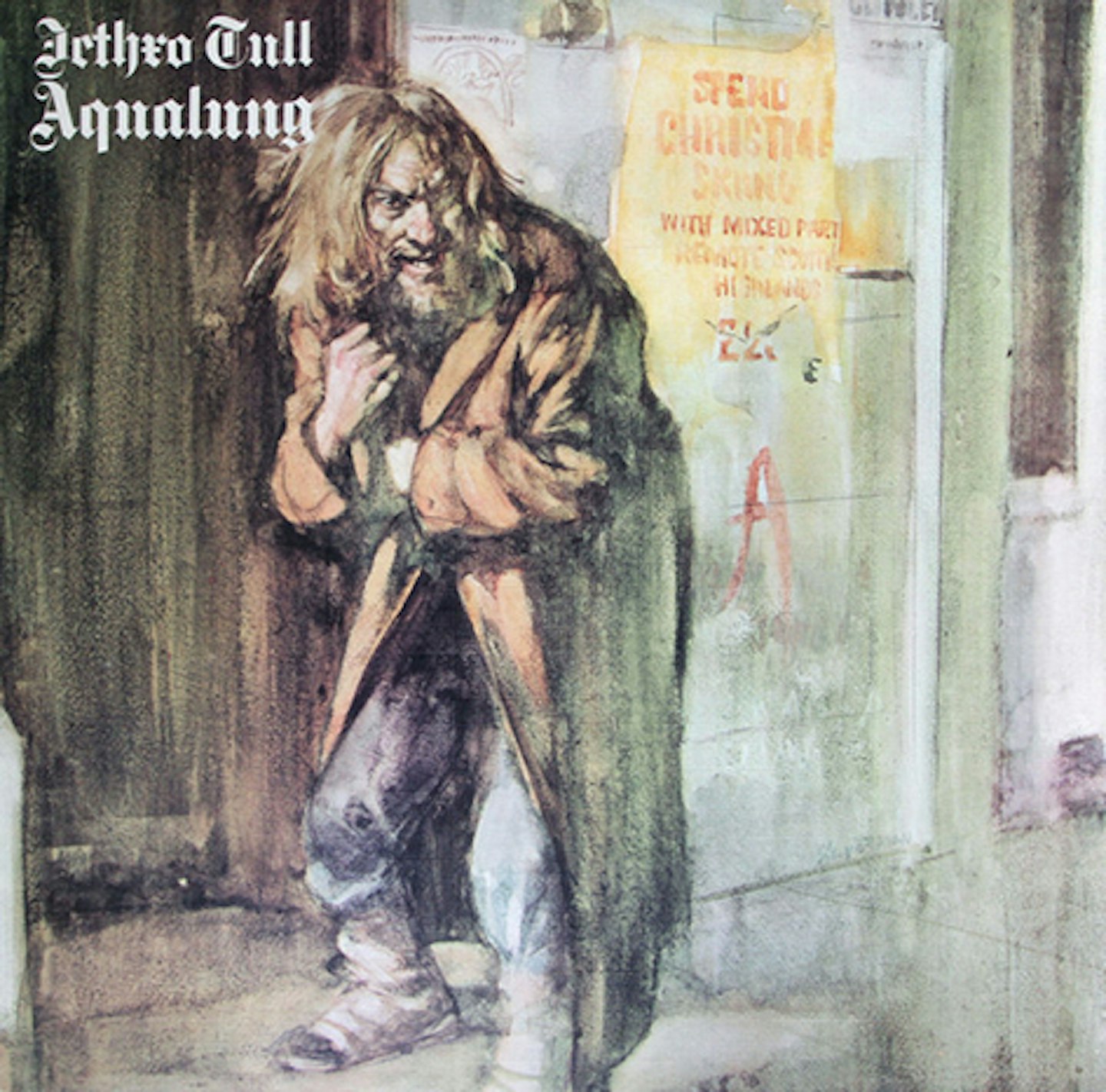

Aqualung

(Chrysalis, 1971)

Inspired by photos of homeless people on the Thames Embankment taken by Anderson’s then-wife Jennie Franks, Tull’s fourth album is their biggest seller (12 million copies shifted, according to Anderson). However, if Aqualung had the brute heaviness to fill gigantic venues (the title track, Cross-Eyed Mary and glowering signature tune Locomotive Breath), it also has metaphysical heft. Inspired in part by fellow firebrand Roy Harper, Anderson’s assaults on organized religion (My God, Hymn 43, Slipstream, Wind Up) led to Aqualung being branded as a concept album, but his bittersweet miniature on visiting his dying father, Cheap Day Return, short circuits any pomposity.

1.

Thick As A Brick

(Chrysalis, 1972)

Nettled that Aqualung was mis-characterized as a concept album, Anderson conspired to make Tull’s fifth LP a knowing pastiche of ponderous, self-regarding rock – but Thick As A Brick ended up being a seriously great record regardless. A suite split into two side-long pieces, co-credited to Gerald Bostock – the boy genius featured in the local newspaper pastiching sleeve – it is a dense tangle of Ray Davies-esque rage about small-c British conservatism and childhood brainwashing; “What do you do when the old man's gone?” bellows Anderson in a burst of Oedipal fury. “Do you want to be him?” However, if it is a sour reckoning with the grown-up world, Thick As A Brick is also playful, questing, passionate. “I may make you feel but I can’t make you think,” sings Anderson at the start of side one, but here Tull manage both. Sharp as a tack, bright as a button.