In 1962, as The Beatles were singing Love Me Do, an 18-year-old Parisian was on the outside, looking in. “I go alone in the streets,” sang Françoise Hardy on her debut EP, “A soul in pain.”

Listen to Tous les garçons et les filles now and it’s easy - especially if you don't speak French - to hear a young sweet girl rocking gently to le yé-yé pop sound. 1962, however, was also the year of Jacques Brel’s Paris Olympia concert, Orson Welles’ The Trial, and first English translation of Martin Heidegger’s Being And Time. Beatnik existentialism, the cold war and Chanson Française were all big news and only one female songwriter was incorporating such existential “shadow of the bomb” ideas into teen chart pop: we underestimate Françoise Hardy at our peril.

Born in Paris on January 17 1944, this strictly-raised convent girl grew up chronically shy, with mere mendicant ambitions until music, in the form of Trenet, Aznavour, Brel, Gréco, and Piaf, and hazy Everly Brothers broadcasts on Radio Luxembourg, changed her world. But after being signed to Disques Vogue as a female Johnny Hallyday in 1961, she insisted on writing her own material. She also became a 60s fashion icon, with admirers including Bob Dylan, Mick Jagger and Nick Drake. But Independence didn't come easy. She retired from concert performances in 1968, defeated by nerves. After protracted legal battles with Disques Vogue she signed with the independent Sonopresse label in 1970, but the creative freedoms she’d longed for didn't translate into record sales.

This tension, between existential despair and romantic yearning, is what defines her finest records, which exist in that delicious suspended netherworld between freedom and compromise, forever waiting for the day, as she sang on Tous les garçons et les filles, “when I will no longer be a lost soul/ [when I] will find someone who loves me.”

In remembrance of Hardy, who died in 2024, we present a guide to her essential releases.

10.

The Vogue Years

(CAMDEN DELUXE, 2001)

Compiled like 2013’s Midnight Blues by Saint Etienne’s Bob Stanley, this stellar compilation collects 50 of Hardy’s finest Disques Vogue work from 1962 to 1967. Sequenced chronologically, it’s possibly the most enjoyable way to learn about how she moved away from early 60s Yé-yé pop, experimenting with elements of folk-rock, chanson, country and psychedelia, incorporating lyrics of emotional complexity and existential depth. Hardy’s first three Disques Vogue releases (recently reissued on vinyl in glorious mono by Light In The Attic) all feature a few duff tracks, but there are no such worries here.

9.

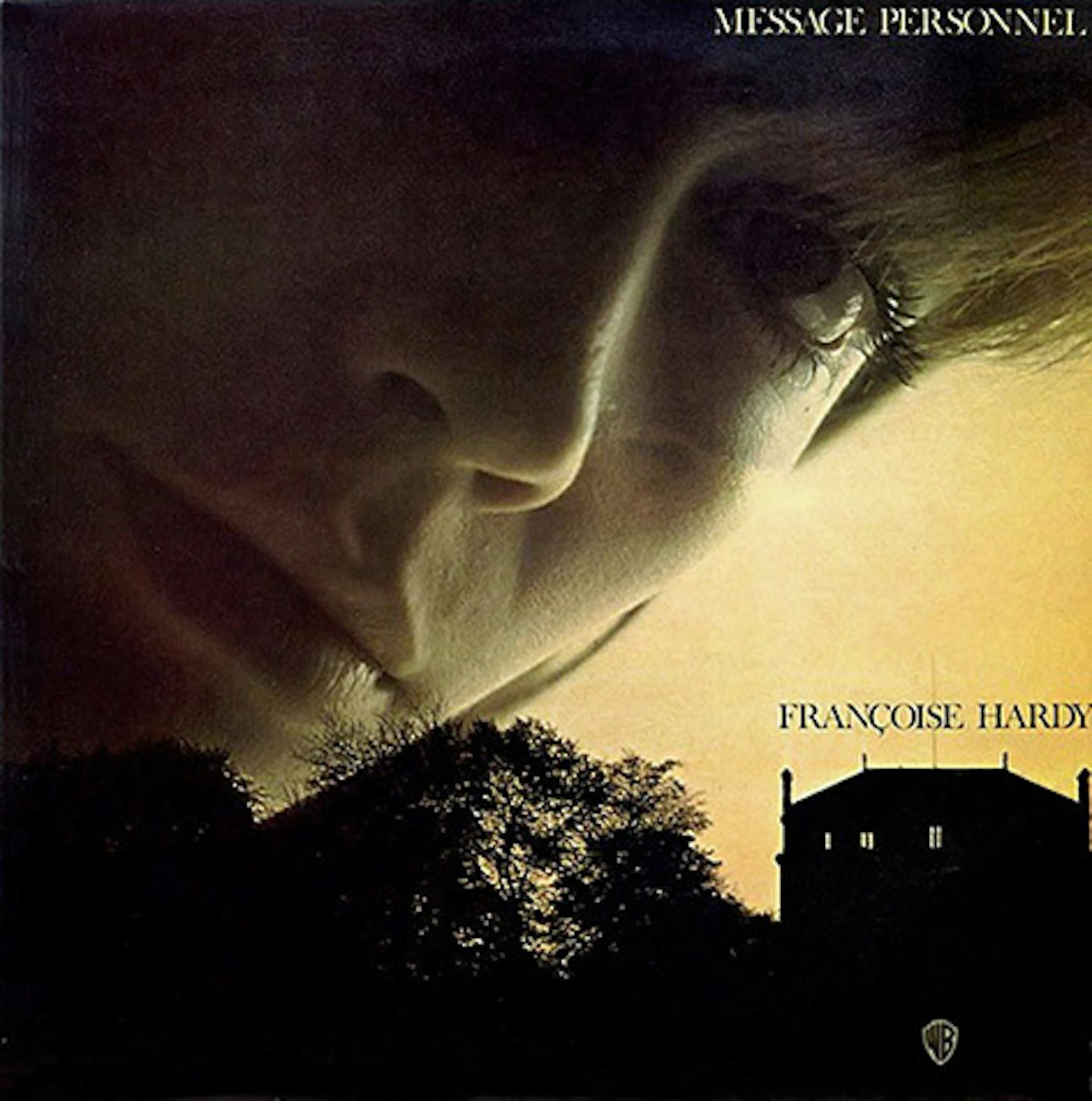

Message Personnel

(WARNER BROS, 1973)

Recorded for WEA with its artistic director Michel Berger, Message Personnel found Hardy working to someone else’s vision for the first time since her Disques Vogue days. Entering the studio still weak, following the birth of her son Thomas, she deemed herself “more an interpreter than a writer” and has mixed emotions about the resulting album. But the results are frequently stunning, from the cinematic strings of Michel Bernholc to the distorted guitars and breakbeats on Serge Gainsbourg and Jean-Claude Vannier’s L’Amour en Prive. The desolate half-spoken/ half sung title track points towards the conceptual narrative of 1974’s Entr’Acte.

8.

Et Si Je M'En Vais Avant Toi

(SONOPRESSE, 1972)

Recorded at London’s Sound Techniques with a band featuring Fotheringay’s Jerry Donohue on guitar, and Dave Peacock of Chas and Dave on bass, this is Hardy’s most overtly country-rock LP. A huge commercial flop, it’s worthy of a revisit, as behind its slide guitars and rocking rhythms are raw songs of emotional disconnect and failed relationships (“He is my stone wall/ And I'm his background noise,” sings Hardy on Bruit de Fond). Bowm, Bowm, Bowm meanwhile, is one Hardy’s loveliest songs, a hymn to meditation (and quite possibly sex) that displays the overt influence of Nick Drake on her songwriting.

7.

L’amitié

(DISQUES VOGUE, 1965)

The second LP recorded in Pye studios in London with producer Charles Blackwell, following a dissatisfaction with Disques Vogue’s in-house arrangers. L’amitié consolidated the new-found confidence of 1964’s Mon Amie La Rose - Hardy choosing her own songs and working with UK session musicians on a sound that combined Spector’s Wall of Sound with freak-beat guitars and country harmonies - resulting in her most enjoyable Disques Vogue release, featuring French chanson with haunted Brill Building melodies, Big Jim Sullivan and Jimmy Page’s fuzzed-up guitars, and, in Hardy’s lonesome lyrics, a world of twilight romance that dies with every sunrise.

6.

Soleil

(SONOPRESSE 1970)

Her first for Sonopresse was recorded in collaboration with the writing/ production team of future Foreigner guitar Micky Jones and his drum partner Tommy Brown, with contributions from novelist Patrick Modiano and arrangements by Jean-Pierre Sabar and Jean-Claude Vannier. Like Frank Sinatra’s Reprise debut, Ring-A-Ding-Ding!, Soleil is something of a defiant fuck-you to the old label, and an attempt to show them how it’s really done. A mature cross between earlier Disques Vogues angst-pop and the late-60s baroque stylings of The Zombies, in sweetly swooning songs like Je Fais Des Puzzle and Fleur De Lune, Soleil blueprints a sound ABBA would transform into a global brand four years later.

5.

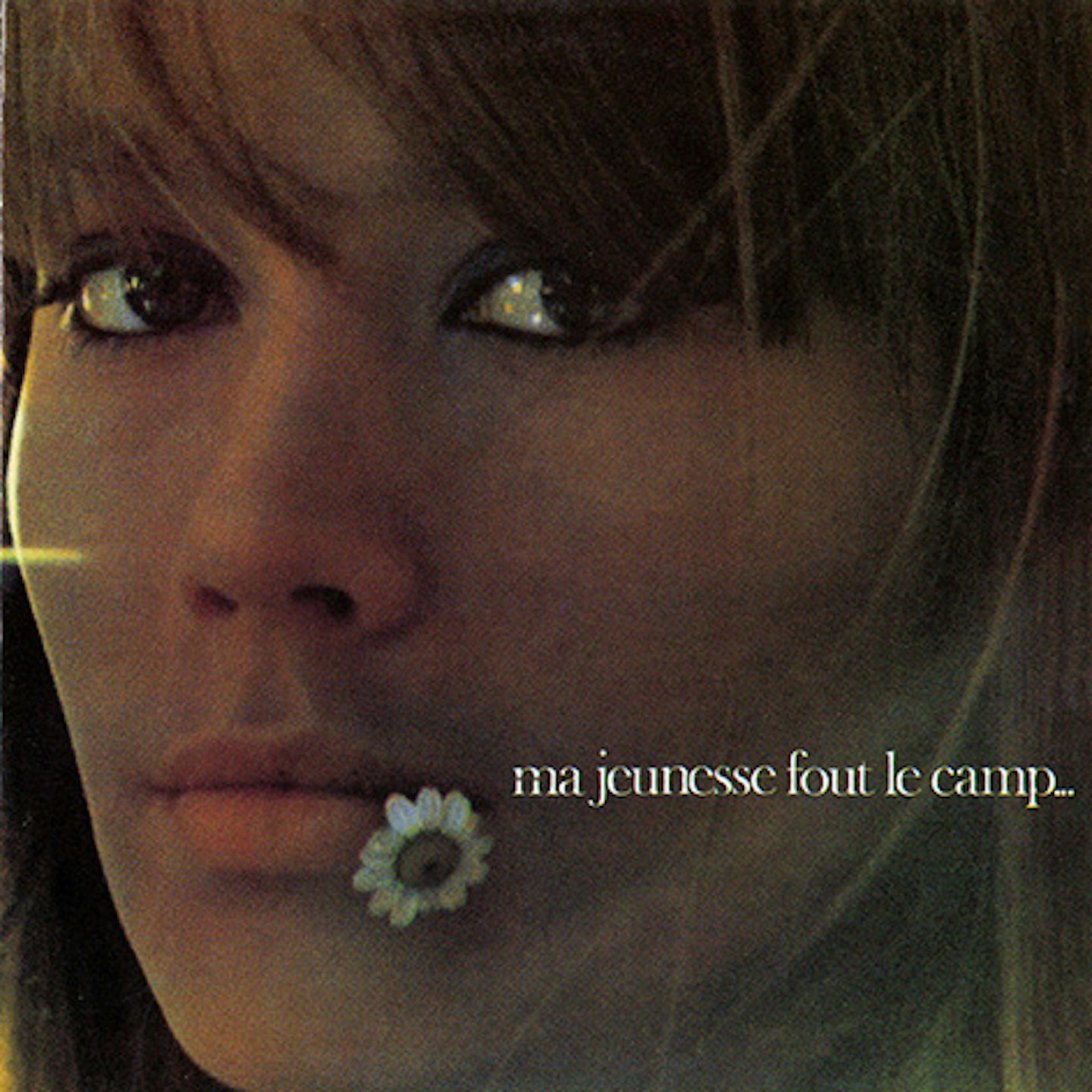

Ma Jeunesse Fout Le Camp…

(DISQUES VOGUE, 1967)

In November 1967, with her Disques Vogue contract at an end, Hardy set up her own production company, Asparagus. However, still managed and distributed by Disques Vogue, she became caught in an unhappy limbo between creative freedom and pop demands. The result is this mournful, introspective act of work-to-rule. With an LP title that can be interpreted as “My youth has fucked off” (Hardy was 23) and song-titles translating as The End Of Summer and There Is No Happy Love, Ma Jeunesse… is the singer at her exquisitely reflective best, aided by the wintry arrangements of future Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones.

4.

Entr’acte

(WARNER BROS 1974)

A concept album about a one-night stand (“an intermission”) with a married man, directed to her husband Jacques Dutronc during a troubled period in their relationship, Entr’acte is Hardy’s most overlooked LP. Although barely thirty, she sings of “a heart that thought itself too old”, the lyrics moving from thoughts of nervous anticipation, to assignation, to post-coital regret (as she sings on Chanson Noire, “From blind insanity/ To lucid despair”). Against lazily sensuous guitar loops, rippling synths, and the softly sighing string arrangements of Jean-Pierre Castelain, Entr’acte is the mournful second act of 1971’s La Question, and almost as essential.

3.

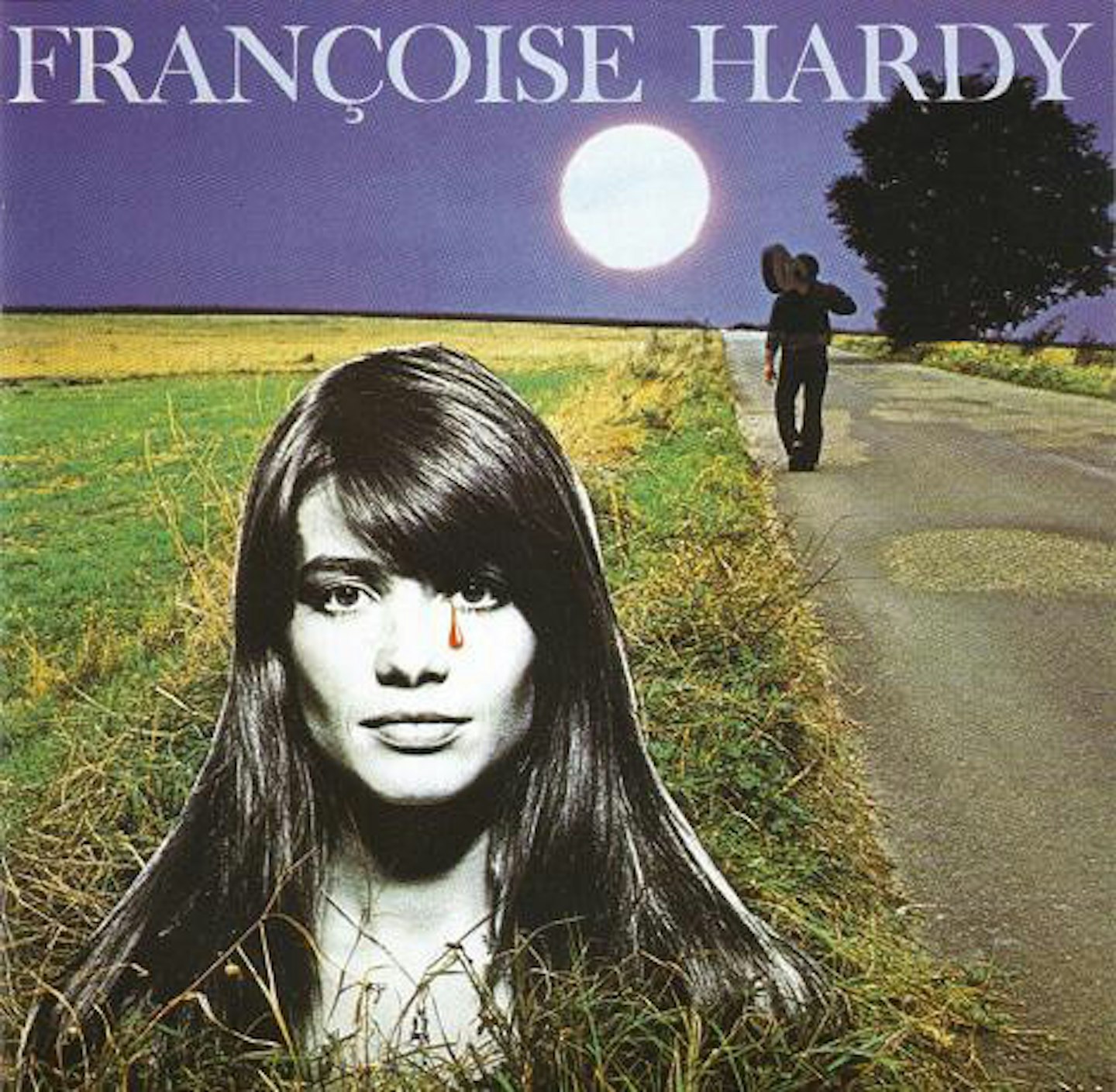

Comment Te Dire Adieu

(DISQUES VOGUE, 1968)

Following the defiant one-note melancholy of Ma Jeunesse Fout Le Camp… for her follow-up Hardy became song-hunter, working with British arrangers Arthur Greenslade, Mike Vickers and John Cameron to refashion Phil Ochs’ There But For Fortune, Ricky Nelson’s Lonesome Town and Leonard Cohen’s Suzanne. There are also tracks by Serge Gainsbourg – at his filthy best on the bitingly assonant title-track and prison masturbation monologue L’Anamour - Antonio Carlos Jobim, and future Nobel prize-winner Patrick Modiano. The result is a baroque orchestral pop LP that in its own subtle way, captures the unrest of Paris ’68; a sense of darkness and swirling unease beneath the urban romance.

2.

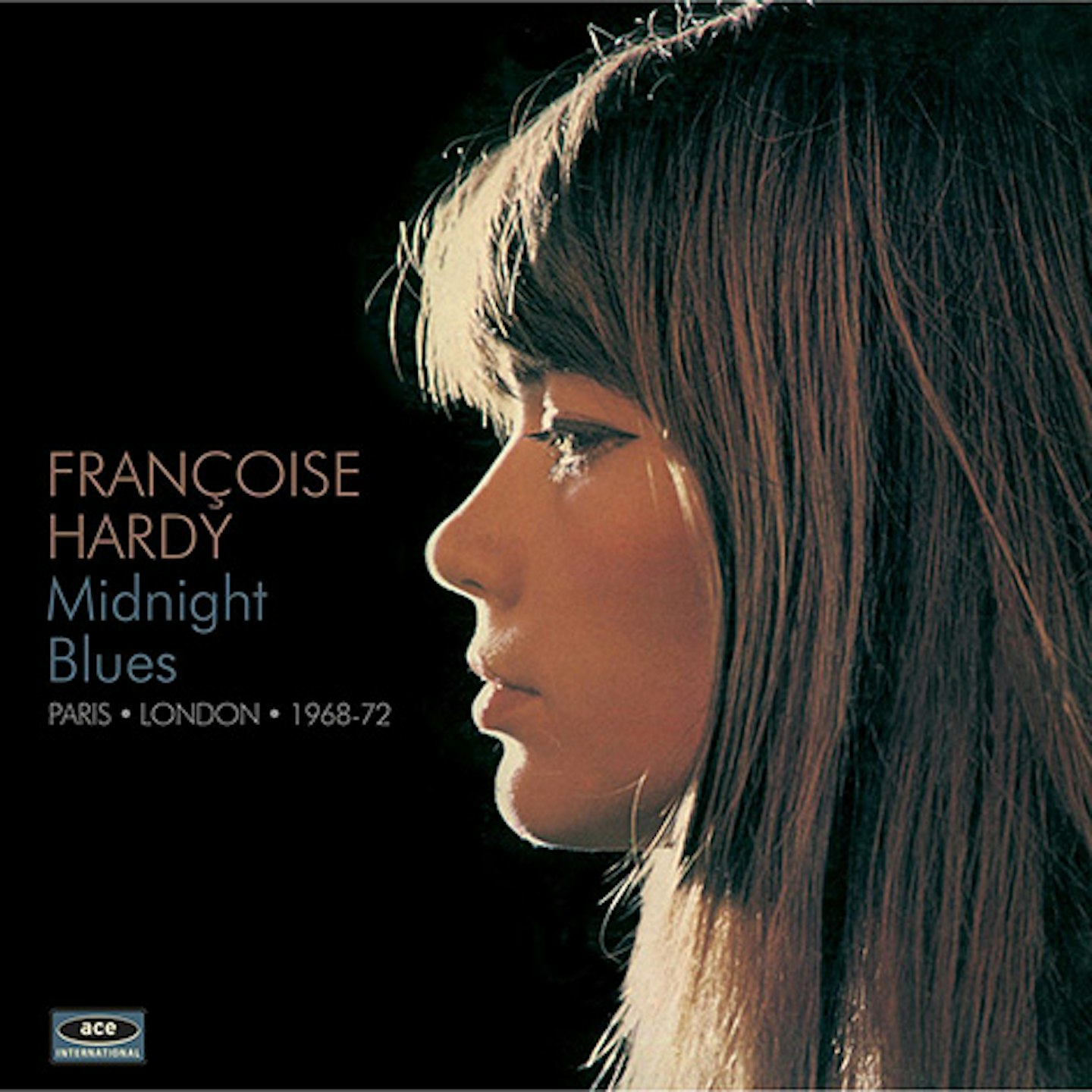

Midnight Blues

(ACE, 2013)

Assembled from three difficult-to-find English language LPs (En Anglais, One-Nine-Seven-Zero and the album eventually titled If You Listen) this 2013 Bob Stanley compilation neatly documents Hardy’s post May ’68 transformation from yé-yé pop chanteuse to moody folk-rock existentialist. Majoring on work Tommy Brown and Mick Jones, plus London recordings with Fotheringay and Fairport Convention alumni (Nick Drake was also present, too withdrawn to contribute) this mix of surprising covers (Beverley Martyn, Neil Young, Trees) and originals is Hardy at her wistful best, her hesitant English vocals adding an extra questioning note to autumnal songs of uncertainty and doubt.

1.

La Question

(SONOPRESSE 1971)

Released on the tiny Sonopresse label in October ‘71, Hardy’s second LP for her Hypopotam production company marks a complete conceptual break from her pop past. Co-written and recorded with Paris-based Brazilian singer and guitarist Valeniza Zagni da Silva - aka Tuca - La Question catalogues the highs and lows of Hardy’s turbulent relationship with Jacques Dutronc and Tuca's own unrequited love for Italian actress Lea Massari. Hung on Tuca’s weightless bossa-nova rhythms and Raymond Donnez’s dark, sensual strings this intense, haunted and hypnotic LP rises and falls with a powerful dreamlike eroticism, caught somewhere between “la petite mort” and death itself.

Now Hear This…

There’s something good on every Françoise Hardy LP, so if you’ve already fallen for her classic 1962-74 recordings check out her disco reinvention on 1978’s Musique Saoûle and 1982’s Quelqu'un Qui S'en Va. Others worthy of investigation include 1988’s Decalages (despite the of-its-time gated-drums production) and 1996 comeback Le Danger, where Rodolphe Burger’s guitar atmospherics assume the role Jean-Claude Vannier string arrangements - it has aged surprisingly well. And if your French is up to it, there’s also Hardy’s 2008 memoir, Le Désespoir Des Singes Et Autres Bagatelles, and, on YouTube, the 2016 documentary La Discrete.

Picture: Mondadori Portfolio