Thanks to a swaggering role in Britpop’s naughty ’90s carry-on, the four men of Blur are haunted by depictions of themselves at their most annoying and cartoon-like. But peer back – into the punky chaos of the pre-Blur Seymour, and back further, into teenage epiphanies aroused by The Jam, The Specials and New Order, into singer/songwriter Damon Albarn’s boho background (his father Keith managed Soft Machine) and apprenticeship in music theatre – and the soul of a fascinating, polymathic pop phenomenon emerges.

As a young indie band on the rise, 1988-91, Blur were rowdy and puppyish. Rhythms were a war between drummer Dave Rowntree’s heads-down flailing and Alex James’ pert, elasto-poppy bass lines. Graham Coxon’s guitars could be relied upon to surprise – his sizzling riffs on Syd-Barrett-goes-baggy single There’s No Other Way were a killer calling card – while his fellow alumnus of Stanway Comprehensive, Colchester, Damon Albarn, wrote the songs and sang with sssibilant esssesss.

They liked to get in your face, often drunkenly, but their big bet, on English-flavoured pop at grunge’s apex, paid off. The subsequent alignment of UK pop culture behind them went to their heads, or did them in, or both, but it’s to their credit that when it came the crash fuelled music that bore the scars, in the scratchy comedown vibe of Blur, the deconstructive urges of 13, and beyond, into idiosyncratic solo projects.

35 years on from the release of their debut single, Blur are still with us. In July 2023 they played two of the biggest shows of their career at Wembley Stadium and released their ninth studio album, The Ballad Of Darren. One of their best, perhaps? Or maybe not? Read on to see where it comes in our rundown of every Blur studio album…

9.

Leisure

Food, 1991

By the band’s own admission, their 1991 debut was an exercise in paddling around in post-baggy, pre-Britpop waters trying to find an identity. As such, much of Leisure can feel underdeveloped or, as on the Madchester beats tacked on beneath the likes of Bang, an exercise in hitching themselves to someone else’s bandwagon. That being said, it’s an album that also contains two bone fide classic Blur singles (She’s So High and There’s No Other Way) and on the churning, narcotic fog of Sing, an indicator of the depths and possibilities that lay ahead.

8.

The Magic Whip

Parlophone, 2013

Stranded in Hong Kong for five days in 2013 after the cancellation of Japan’s Tokyo Rocks Festival, Blur knocked up an entire album’s worth of new material in their downtime, which Graham Coxon later took to Parklife/Modern Life Is Rubbish producer Stephen Street to polish up enough to convince Damon Albarn they had a Blur-worthy collection on their hands. Despite its ad-hoc creation, The Magic Whip provided a fine comeback. Humid and tightly-packed, with the hum and buzz of Coxon’s guitars stuttering and spluttering throughout, here was Blur in their 40s: world-weary at times and audibly frazzled, but reconnected to their spirit and identity in way that we hadn’t heard since the end of the '90s.

7.

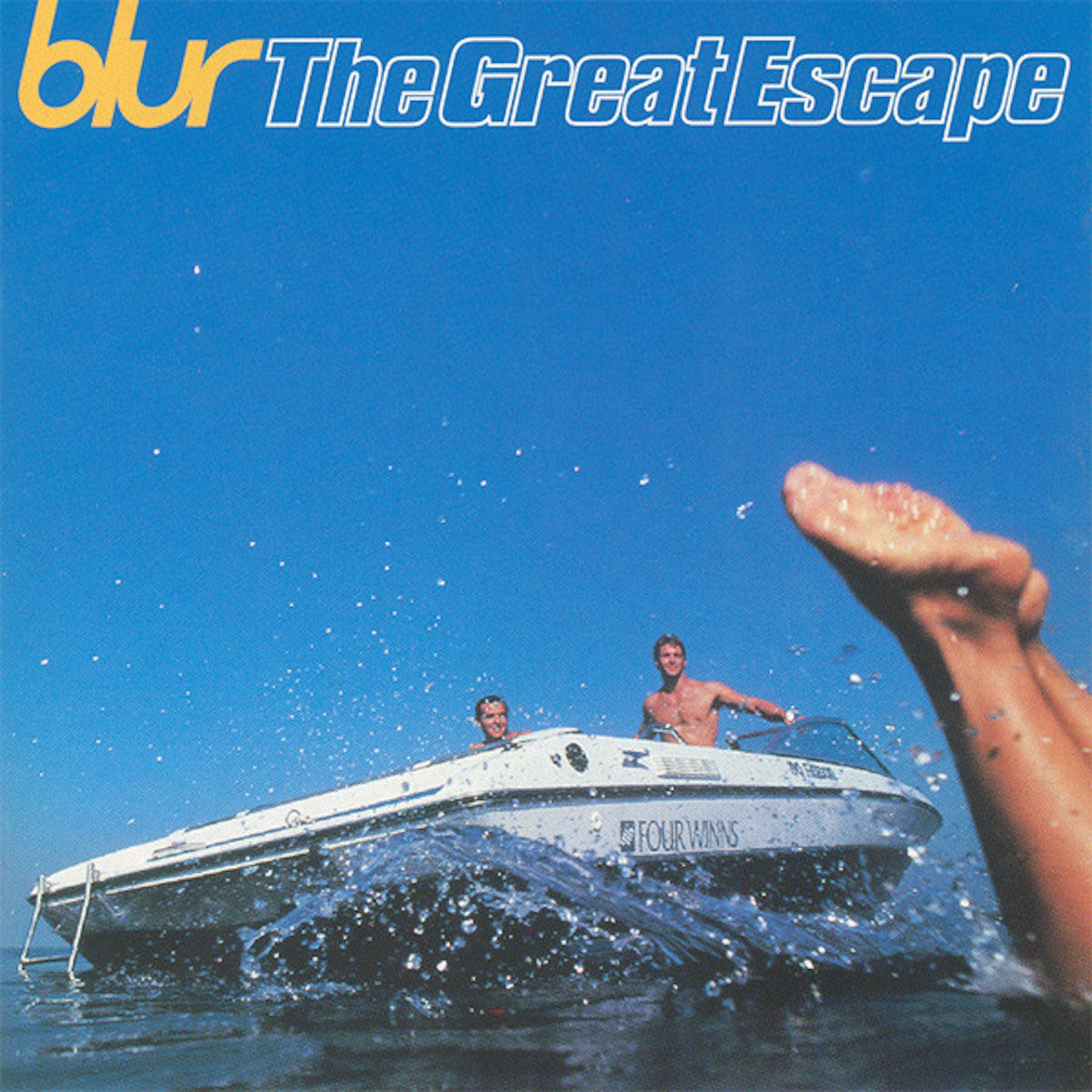

The Great Escape

Parlophone, 1995

The final instalment of Blur’s ‘life’ trilogy, The Great Escape may have felt like Parklife Pt2 in some respects, but it’s also an eerily accurate bellwether of British pop culture in the mid 90s. The Oasis-squashing Country House reveals a new level of irony when you realise it was sending up Food boss Dave Balfe, and while Charmless Man and Stereotypes may now sound like brash cousins of more detailed character studies like Tracey Jacks or For Tomorrow, The Great Escape also contains some of Blur’s finest ever moments: Scott Walker homage The Universal and He Thought Of Cars – a seasick knot of distortion and melancholy that pointed the way to a richer future away for the shadow of the Britpop monster they had helped to spawn.

6.

Think Tank

Parlophone, 2003

Given the mid-project departure of Graham Coxon (at least he left the vertiginous guitar nuages of epic closer, Battery In Your Leg) this is victory from the jaws of defeat. Recording in London and Marrakesh, with the help of Norman Cook, and with The Clash’s Combat Rock on Albarn’s mind, Blur hosted a multi-ethnic meltdown on their blithest record since Britpop flag-bearer Parklife, with Maroc-punk nuttah We’ve Got A File On You and Black Grapey drug-paean Brothers And Sisters balancing the transfiguring, melancholy pop of Out Of Time. A slightly patched-together, demo’d vibe adds charm but – surprise – it lacks something. That’s it: Graham Coxon.

5.

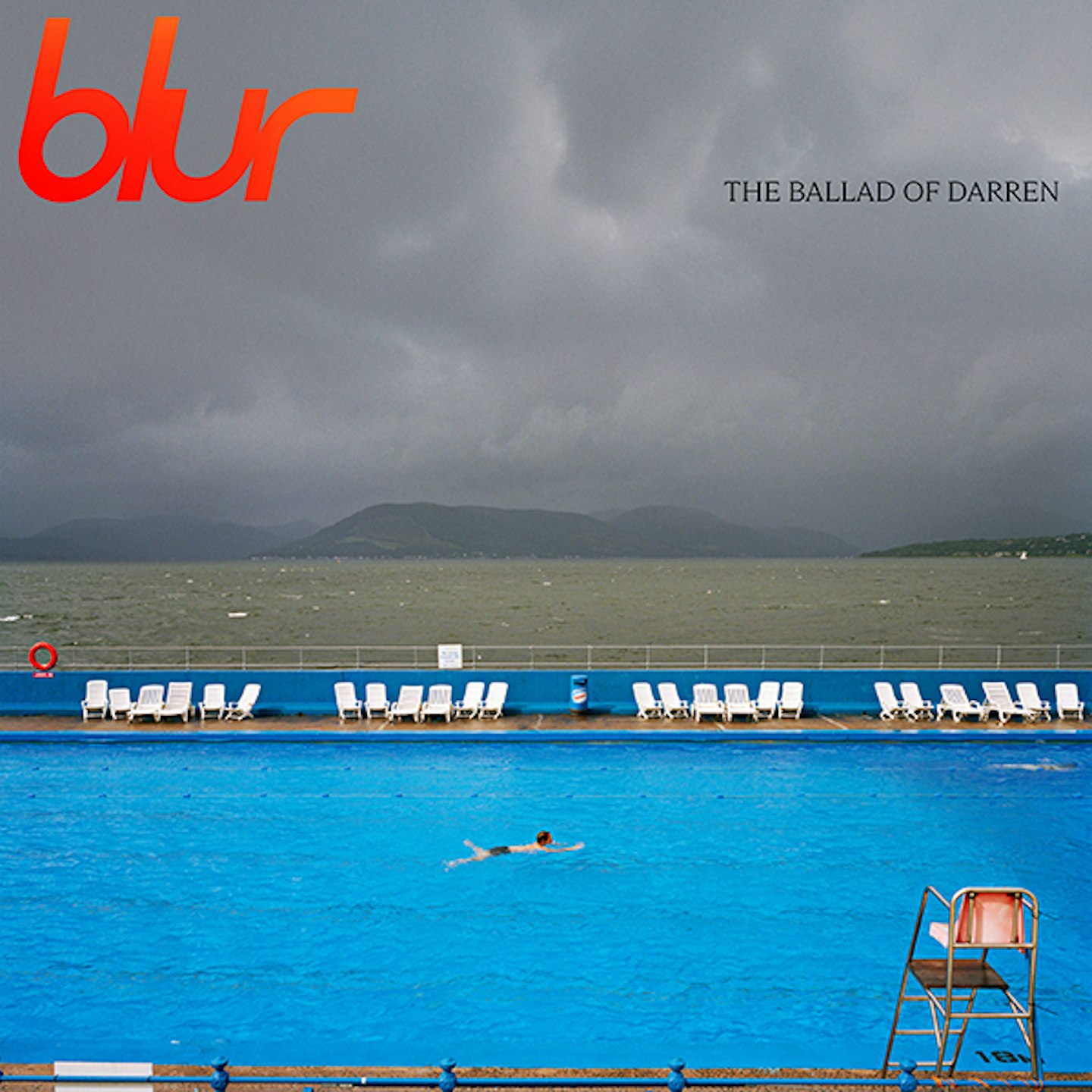

The Ballad Of Darren

Parlophone, 2023

Perhaps it’s too early to tell where Blur’s ninth album should fall in a rundown of the band’s greatest work, but The Ballad Of Darren certainly sounds like the record Blur should be making in 2023. With the group themselves playing two nights at Wembley Stadium shortly before the record’s release, Britpop nostalgia is clearly a booming business still, yet the looking back that takes place here isn’t a cheery hark back to past glories, but a sadness for what’s been lost as the band navigate middle age together. Despite its glammy guitar stomp, and even an ‘Oi!’ from Albarn, St Charles Square paints a picture of the singer broken by fame, hiding from success and succumbing to the fear (and worse), and when Coxon joins Albarn to sing of travelling around the world together on The Ballad it’s a bittersweet acknowledgement of their shared lost innocence. As Coxon told MOJO recently: “It sounds like Blur, but men.”

4.

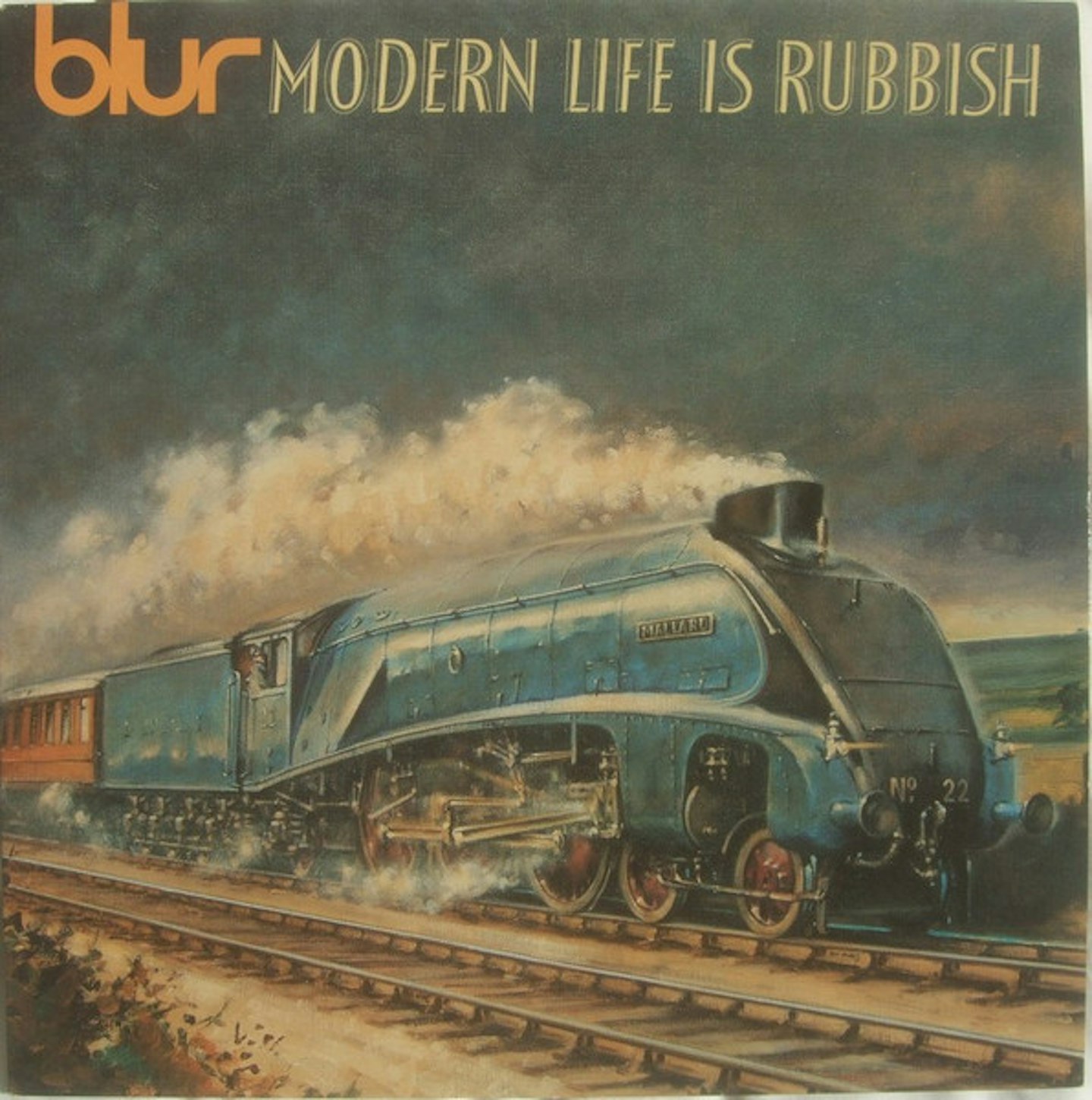

Modern Life Is Rubbish

Food, 1993

Much truer to Blur’s art-punk soul than their nebulous debut, Leisure, this could still have been their last gasp without the intervention of the Food label’s oft-maligned Andy Ross/David Balfe axis. Their demand for singles gave rise to Chemical World and the aching For Tomorrow, Albarn’s first mature conceptions. Meanwhile, Modern Life… looks back, in Colin Zeal’s homage to The Teardrop Explodes’ Went Crazy, and forward, in Starshaped’s pre-echoes of End Of The Century, and Coxon rocks harder than on any Blur album. Bonus: 2012’s two-disc reissue gives you the pivotal Popscene. “Lost on the Westway” was Albarn, not for the last time.

3.

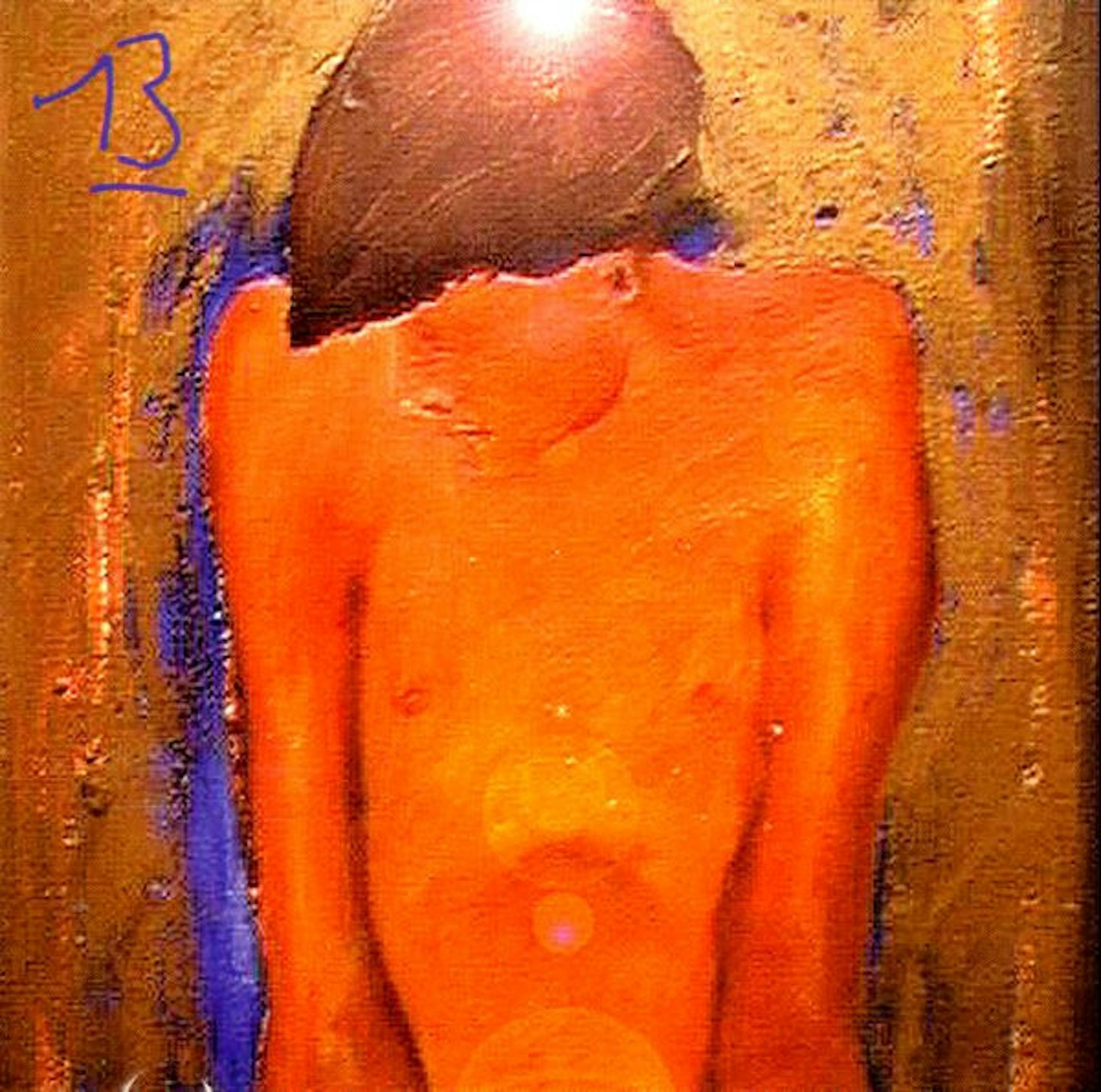

13

Food, 1999

In the late ’90s, experimental drug use turned Albarn on to music’s texture, groove and soul, while William Orbit’s mix of the Blur album’s Movin’ On convinced the group of the uses of electronica. Orbit would produce 13, taking the bonnet off Blur and exposing its innards – the raw nerves of Albarn’s split from Britpop consort Justine Frischmann included. Stompy gospel-folk (Tender) and gnarled pop (Coffee & TV) thus met indie-dub (Battle) and opiated prog (Caramel) in a trip into inner and outer space. Sadness and weirdness combine in the devastating closing song No Distance Left To Run and in Trailerpark, the roots of Gorillaz are beginning to show.

2.

Blur

Food, 1997

The patient on the cover’s gurney could have been Blur themselves, ravaged by Britpop excess and the Pyrrhic skirmish with Oasis. In its wake Graham Coxon, disaffected by The Great Escape’s overwrought Parklife redux, got what he wanted: a re-indiefied Blur complete with lo-fi scuff and a heart of darkness (his You’re So Great could be Dinosaur Jr.). And yet Classic Blur™ tropes shine through: clever/dumb pop gambits like Song 2 and M.O.R.; Ghost Town overtones in Britpop time-caller Death Of A Party; the Hunky Dory-isms of Strange News From Another Star. Simultaneously Blur’s most fatigued and yet effortless album.

1.

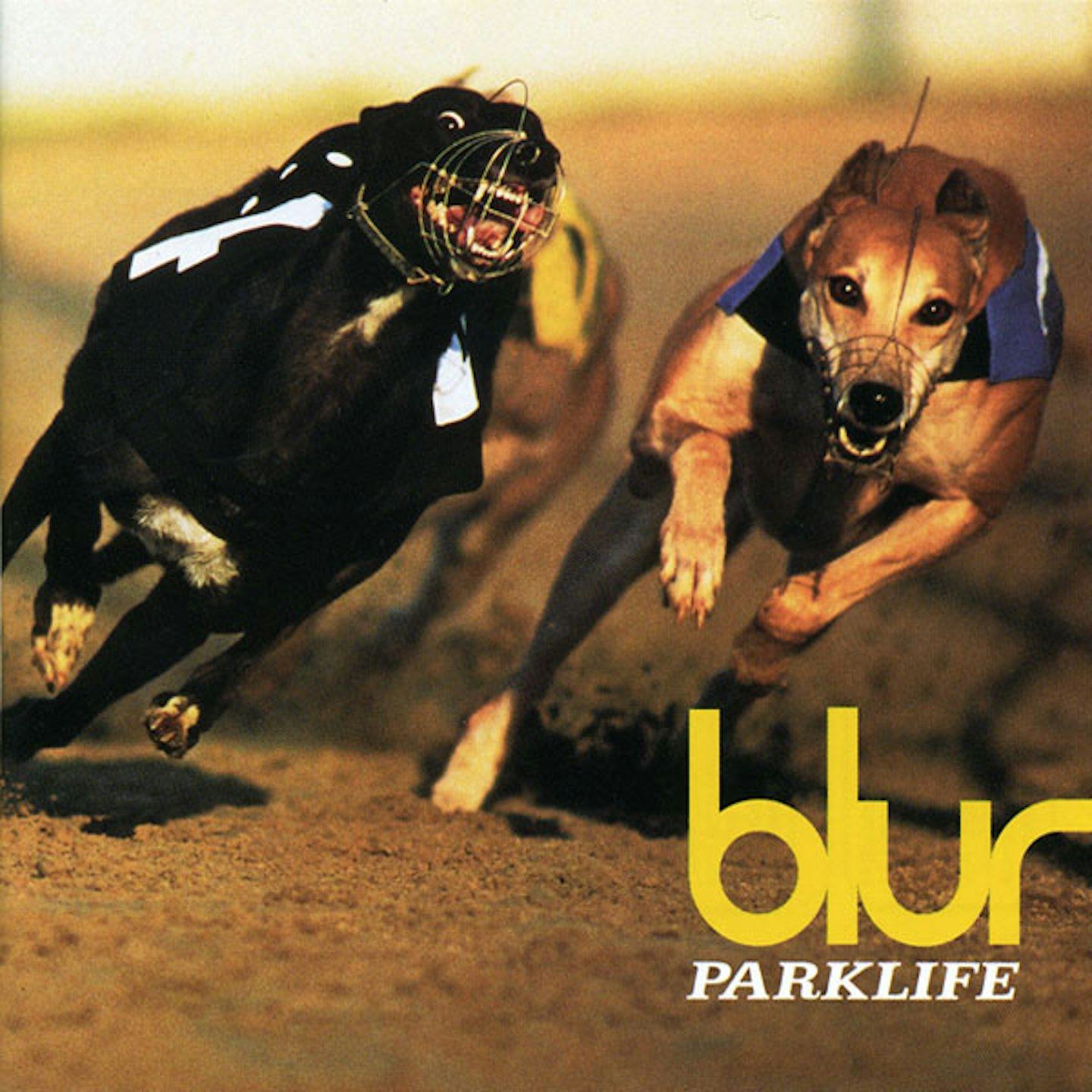

Parklife

Food, 1994

Everything haters hate about Blur, with its yob-march title track a kind of pustulant, contempt-attracting beacon. But don’t blame Parklife for the excesses of the era it presaged with its artful brashness and pop-art palette (a bit like Alf Garnett – you saw the cautionary irony, or you didn’t). Admire instead the heady alt disco of Girls And Boys, swaggering ultra-Kinks of End Of The Century and the Elgarian melancholy of This Is A Low: key planks in an accidental state-of-the-nation address laced with brio, stylistic dressing-up and tunes. Sometimes records are successful because they are great. This is one of those.