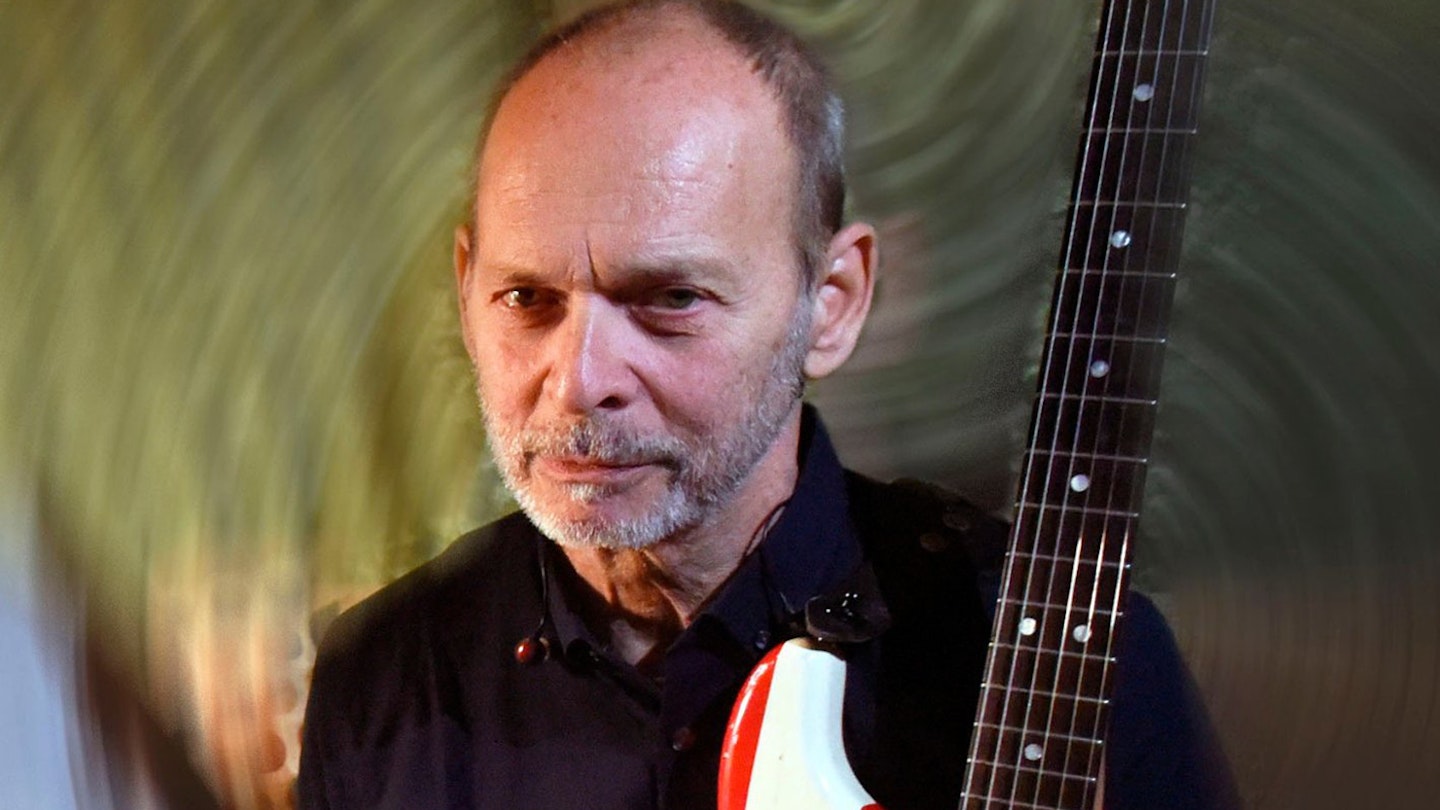

On the eve of his 70th birthday, Wayne Kramer has been rebuilt inside and out. “I’ve got a titanium cage holding my spine together. I have implanted teeth. I have a hearing aid. I’m like the bionic man over here,” he says, cackling.

MOJO has travelled to Hollywood, to the offices of Industrial Amusement Inc., the studio and business HQ belonging to Kramer and his manager/wife Margaret Saadi. The walls are adorned with images and iconography from Kramer’s life and career, including his famed stars and stripes Stratocaster. Especially prominent is a blown-up mug shot from Kramer’s ’70s incarceration, bearing the lyrics of Jail Guitar Doors – a song which The Clash wrote in tribute to him, and which now serves as the name of the non-profit prison music program he leads.

On this day, Brother Wayne – somewhat diminutive, deeply articulate and unaffectedly charming – is looking backwards and forwards at once. He’s putting the finishing touches to a memoir, due this summer, titled The Hard Stuff: Dope, Crime, The MC5, And My Life of Impossibilities (Faber Social). It’s a rollicking account of the life of the man born Wayne Stanley Kambes – from his rough upbringing in post-war Detroit, to his transformation from greaser guitarist to rock’n’roll revolutionary.

Following the demise of the MC5 in 1973, Kramer’s life unfolds like an Elmore Leonard novel, as he ditches the stage for the underworld, eventually landing in prison. Released, he slowly emerges from addiction to find his place as a revered solo artist, activist, and survivor. His memoir ends with a twist, as he becomes a father for the first time in his late sixties, with the birth of a son, Francis. “I wanted to write a book that was broader than rock music,” says Kramer in still Michigan-inflected tones, “one that would take into account a more human path that someone might be able to find something useful in.”

This year, nearly a half century after the release of the MC5’s explosive debut Kick Out the Jams, Kramer is hitting the road to celebrate the record and the band. The Kramer-led “MC50” tour will feature members of Fugazi, Soundgarden, King’s X and Zen Guerrilla, filling the roles of departed MC5ers Rob Tyner, Fred “Sonic” Smith and Michael Davis (surviving drummer Dennis Thompson will appear on a handful of dates). “These guys all have a personal connection to the MC5,” says Kramer of the players he’s assembled. “This ain’t just another gig they got hired for; this is a mission.” The tour – an ambitious 70-city international trek – will arrive in the UK this autumn. “I’m looking forward to playing the songs again and having some fun. I mean, I’m 70 years old,” Kramer says, grinning, “I’m gonna do what the fuck I want to do.”

Your father – a war veteran and alcoholic – split with your mother when you were a kid. His absence feels like the defining factor in your life.

My mother was a wonderful woman who showed me a lot of love. But not having a man in the picture left a big hole for me. The appreciation of a father, the acceptance of a father, the sense a boy can get from his father that you did something good – “You did alright, son” – I didn’t have any of that. So, I had to get it someplace else. That’s one of the things that drove me career-wise. Anyone that works as hard as you have to just to put yourself in a position to be on stage, in front of a thousand people, and then demand that they love you – well, something is terribly wrong with you (laughs). This is not a healthy mental state.

You changed your name so that when you got famous, your father couldn’t benefit from the association. But much later in your life, just before he died, you reconnected with him – what was that like?

It meant rethinking everything. It meant having those negative feelings dissipate and reality come into focus. To actually learn what happened to him – he was suffering from PTSD. He went through horrible shit in World War II, those campaigns in the South Pacific were horrific, and nobody knew how to treat people who had gone through those kinds of experiences. And he did what humans have always done – he medicated his damaged psyche. We talked about his alcoholism. When he worked in the steel mills in Pennsylvania where he lived, he was an electrician and he would make his rounds and hide liquor bottles in fuse boxes all over the factory so he could maintain his equilibrium as an addict. It’s like, I get it! That makes sense to me. That my mother couldn’t cope with his disability makes sense to me. When I was a boy none of this was clear. It was all just hurt and anger.

You grew up in the Detroit of the ’50s and ’60s, fighting and stealing. Were you one of those people who didn’t have a fear of consequences?

I knew full well stealing was wrong – but the rewards were greater than my fear of getting caught. This is the magical thinking that followed me through my adult life. (laughs) Fighting was one thing on a long list of teenage concerns. But my anger, I could always plug into that. And if I got mad, it was war. That probably that showed up later in my addictions too. Generally, I wouldn’t get mad – I would get high. I would stuff my feelings down. I was afraid of my anger. Because when I got mad people got hurt and crazy shit happened. It was easier, safer to get loaded than let my anger out.

Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Duane Eddy served as your musical foundation. What was the attraction?

The level of sheer exuberance that came out of Little Richard records – Earl Palmer’s drumming swung so hard, and Richard’s vocalizing and piano playing were so enlivening. Or Chuck Berry – the velocity of the guitar playing. Even Duane Eddy in his own way – there was a tremendous energy level to that stuff that appealed to me instinctively as a boy.

But it was seeing the 1964 movie T.A.M.I. Show – especially James Brown and the Rolling Stones – that crystallized things?

The whole context of the film, it was so broad. All those different artists together performing live and so many of them were my favourites. I mean, Chuck Berry was on that show, Motown artists, the Beach Boys – who I loved – even the British first wave bands, who were a little syrupy, but still I liked them. But the Rolling Stones and James Brown was something else. It was like here’s the roadmap. I knew I couldn’t be James Brown,he was like from another dimension. But the Stones, I coulda been any of them, they were kids like me.

You and a couple other kids – Rob Tyner and Fred Smith – had started playing together in what would become the MC5. Why were you drawn to each other?

Fred found, in me and Rob, people he could talk to on a level that he couldn’t with other kids. Like me and Fred fell in love with Ian Fleming novels – we would read them and compare notes. My attraction to Tyner was his intellect. He had such a vision of the future that he could articulate. He was a great artist – he could draw, he designed all his own clothes. He was singular, unique. Almost to the point that I didn’t really appreciate him in the early days, as much as I do today. Plus, he was everyone’s dream as a lead singer. And he was always a step ahead. Always.

The MC5 sound was built around your guitar interplay with Fred – why did the two of you work so well together?

It may been the fact that I was his tutor in the early period. I showed him how to play things – like he would play the rhythm part and I would play the melody. He was amazing in how he could hold onto a figure and play it endlessly. This came from us learning Chuck Berry songs – it’s hard on your forearms and hands to play those songs. It’s the Chuck Berry workout! We could depend on each other, which gave us an inter- independence. Also, Fred and I never competed. We achieved a kind of ego loss when we played together. Music for him was a voice to express complex feelings and troubled thoughts that he had. It was a way for him to say, ‘This is who I am’ – just as it was for me. We supported each other in that.

The embryonic MC5 gigs around Detroit – what kind of band were you then?

From the outside, we were probably a terrible teenage boy band trying to figure out how to play our guitars –but from the inside they were the most exciting things I’d ever done. Playing was a transformative experience. We know now that playing music uses up more CPU power than anything in our lives. It’s more than language, more than writing. There’s so much going on. It’s a total immersion and your brain is firing on all circuits. There’s nothing like it. It becomes like an addiction. We were wild onstage. If you just stood there and played you were ho-hum. Unless you were some great musician – but most us weren’t great musicians. So you had to figure out something else to do. That’s where the showmanship of the MC5 came from.

Eventually the twin influences of marijuana and avant- jazz came to play a part in what the MC5 would become.

The Beatles and Stones had hit, and that opened my eyes. It was like, OK, you can write your own songs and play concerts instead of just clubs or dances. But everything was still fame-based, showbiz-based. It was about being a hit pop band, being a success on that level. It wasn’t art. And it wasn’t politics. Like I say, Tyner was always head of the curve, he really embraced the coming counterculture. We started smoking reefer and then I started to wonder, Okay, there are all these bands trying to do something – what’s going to make us different? If I played my best Chuck Berry solo as fast as I could play it, as hard as I could play it, turned my amp up all the way, got the most distortion – where could I go from there? And when I heard John Coltrane and Sun Ra and Albert Ayler – I said, Oh, that’s where you go from there. You leave the key and the beat behind and go into a kinetic, more purely sonic dimension, where you’re trying to reproduce human emotion in sound. Thinking in terms that broad, I started to see there was actually a political component to what art could be.

Helping you in that process was [poet/political activist/White Panther Party founder] John Sinclair, who became your manager.

John was a little older than us, a little better educated and was able to articulate conditions – the way the world was, the way music was and how these things all fit together. His analysis was brilliant as far as I was concerned and I embraced almost everything he talked about. And honestly, we could not have been managed by music biz-type people. We were too crazy.

Even on a bad night the MC5 were still devastating. We

could do things that no bands could do.Wayne Kramer

The MC5’s debut album Kick Out the Jams – you describe it as an imperfect document of your live show.

Sometimes we would be cosmic and sometimes it’d just be spectacular. (laughs) Even on a bad night we were still devastating, could do things that no bands could do. Certainly, no American bands could come close to the performances we were capable of. The Who and the Rolling Stones, of course, were the league leaders. But in American rock, at that time, there was no one that could touch us. That’s why bands didn’t like to play with us. All those San Francisco bands were like, “No, no, we won’t play with them.” Same with the New York bands. Nobody wanted to play with us ‘cause we would kill them.

One group that did play with you – and whom you helped **get a record deal – was your “baby brother” band, The Stooges

**I thought they were important and vital from the first performance. Iggy’s dancing was mesmerizing. They were able to maintain their own identify and develop it in the shadow of the MC5. We all listened to the same records, we all jammed together, we all smoked tons of hashish together, we ate together, had the same girlfriends, went over to each other’s houses to commiserate with each other. But Iggy always had a clear idea of what he wanted to do. They were anti- intellectual in a way. They weren’t into deep analysis, but they always had a unique take on shit.

Although the MC5 were revolutionarily inclined, radical political groups like the Students For A Democratic Society and the Motherfuckers turned on you, decried you as sellouts. Did it feel then, maybe as now, that politics and rock’n’roll don’t always mix well?

It was damaging, and I couldn’t understand at the time why our own brothers would hammer us so bad. It is a problem that the left has always had – the circular firing squad. Music has a role to play in inspiring change, but it may not be the role that we started off in the MC5 assuming. We can carry a message, we can inspire people, we can help create community. If you love a song and I love a song, we’re meeting in that place. Bob Dylan’s songs were great at creating a generation of people that felt like a community. That is a powerful political tool. Can that most powerful political tool bring down Donald Trump? I don’t think so. We’re gonna need the Supreme Court or a tough federal judge to do that.

At the time, did you understand how much of a threat bands like the MC5 and organizations like the White Panther Party were seen as by the establishment?

We knew there were forces against us, but what we didn’t know was how serious they were. To find out later that they came from the White House, the Justice Department and they were concerted, organized, plotted, planned campaigns to disrupt American dissent, that was an eye opener. We first found out in the White Panther wiretapping trial, and later it all came out. They succeeded, in a sense, in beating people down. But, in the main, I think the efforts of my generation were successful. The war in Vietnam ended, Civil Rights became an above ground issue – one that we’re still dealing with. There were a lot of legislative improvements. And there was a consciousness that people had more power than they previously believed they had.

The MC5’s second album Back In The U.S.A. was a sharper, tighter and more contained record than your debut. Was that a reaction to some of the negative critical response to Kick Out the Jams?

When you’re young, you take everything to heart, everything is personal. And when [noted rock critic] Lester Bangs said I couldn’t tune my guitar that really ground my balls. I was really unhappy about that. And I was determined this next record was going to be rock solid. And we went too far with it – as young people often do. Hit songs then were Bridge Over Troubled Water, and Take Me Home Country Roads, and we put out this record with Chuck Berry and Little Richard covers on it. You couldn’t have been less fashionable.

By the time you get to the last MC5 album, 1971’s High Time, the wheels are coming off the band. You’re being attacked by your now incarcerated ex-manager John Sinclair, you’re fighting with Atlantic records, there are battles within the group...

No wonder I turned to heroin and Jack Daniels! (laughs) Since I was a boy, and learned to play the guitar and wanted to be in a band, I had worked for this thing. And it was 24/7 – every fibre of my being went into that. By this time there’s forces at play that were beyond my control. I couldn’t control what the Left thought about my band, I couldn’t even control my band. I couldn’t control business, I couldn’t control record companies, I couldn’t control John Sinclair... lack of power was my dilemma. Subconsciously, I decided I need some relief... and I found it in drugs and alcohol. When it fell apart I lost my way to make a living, I lost my friends, I lost my status in the community, I lost my future. I didn’t know how I was going to survive. It became easier to just get loaded.

Thus begins another chapter for you – your life as a professional criminal.

I was so tangled up and rudderless. I found that doing wrong was a way of getting attention too. You could be a “star” in the criminal underworld, you could get recognition that way. When I would do something bad and crow about it to my crew, I’d get some credit for it. Truth is, I was angry at the music business and angry with everything I had tried to do before. Being a criminal was like existing in a reverse world wherewhat used to be considered bad was good, and what was good was for suckers. It all fit into my anger, my cynicism, about everything.

When you’re breaking into someone’s house, I imagine there’s a charge – is it the same excitement as going on stage?

No. Because stealing immediately led me to heroin, which led me to feel better. The drug itself was the reward. I got to feel better and I didn’t have to do all the work of putting a band together, or writing songs, or playing the gigs. That’s the trouble with heroin and opiates – you can feel better automatically. You don’t have to do anything. It’s a short cut.

Eventually, you got arrested on drug charges and faced a 15-year term in federal prison. You write that “I had waited all my life to fuck up this badly”.

I was probably always destined for prison. I did things according to my own rules my whole life. At a certain point you’re going to run into a conflict with the world, with society... with the police. And then they gotta do something to you, they gotta get your attention.

You found music again in prison, playing with imprisoned ex-Charlie Parker trumpeter Red Rodney.

Music was an identity. I didn’t have to have this gangster persona. I was the white boy with the wah-wah. I could really play the guitar and people appreciated it. People in prison are just like people on the outside – if you’re good at what you do it’s valued. Every Saturday, when Red and I played they knew they were hearing world class live music being performed – it just happened to be in a federal prison yard.

You caught a break and ended up serving just three years. You were released in 1978 into a new world, one in which punk rock was happening. Were you aware of the changes in music while you were away?

To an extent. I was friends with [rock critic/musician] Mick Farren and we would write and he kept me posted. And I had subscriptions to magazines so I would read Billboard and could see this band the Ramones – who all looked like Fred Smith – and they would mention the MC5 was a big influence. I didn’t want people I was doing time with to know about that, ’cause they called the music ‘punk’, and punk had a different meaning in prison. Punks were the guys they had washing their socks. And I wasn’t that kind of punk. (laughs)

Fresh out of jail, and presumably trying to stay away from drugs, you elect to start a new band, Gang War – with Johnny Thunders of all people.

(Laughs) Yes, I had many lessons yet to learn. I figured it was probably doomed, but I also thought this could be my ticket back into the rock world. I could see the fans loved this kid. Funny thing was I’m old school, I’m from the generation where we honored our fans, we had a connection with them. And Johnny would just abuse his fans, he would spit on them, and they would love him more for it! There were moments, though. We would play a little club somewhere in Delaware and he would be just brilliant. But then we’d play a big club in Manhattan with record company executives there and he takes three Placidyls before the gig and... you can’t rescue that.

It seems the 1980s were a lost decade for you. You played some music, but mostly worked as a roofer and carpenter, moved around to Key West and Nashville, and kept drinking and drugging.

A lost decade – that’s a good way of putting it. I tried so many things. The experience with Thunders was a mess. Then I led a band in New York for a while and couldn’t get any traction. I was just dazed and confused for a long time.

What snapped you out of that?

The death of Rob Tyner [in 1991]. That was a huge wake up call. It made me confront my finitude, that I only had so much more time. I figured, OK, if I’ve got 20 or 30 more years left I better get to work making music. I was so happy to sign with Epitaph and Brett Gurewitz [in the mid-’90s] and be with people that were behind what I was trying to do. I got back to the work of being a professional musician. It’s been a process of growing for me, of learning to leave behind drinking and drugs – where I don’t need to change how I feel. I can take pride in the work that I do instead, and rebuild some of the dignity I lost on my trip to gutter and some of the self-respect that I threw away.

Looking back now, would you have traded your musical achievements for a more stable life?

That's speculating on a level I can’t get to. I have thought what would’ve happened if a few things had gone right in the MC5. If we had become the premier American hard rock band, and were part of ‘classic rock’ and played on the radio all over the world. And my guess is... I’d probably be dead. Because I would’ve been able to afford more drugs than I could handle. This business has a high attrition rate. In a way, being a poor starving junkie kept me alive longer than being a wealthy junkie, where I would’ve poured the drugs down my veins.

The MC5 has always had the admiration of fellow musicians – is that gratifying for you?

I've always been proud that we’re thought of as a musicians’ band, or an influential band – even though in some quarters they didn’t hear it. It was only complicated to me in that it seemed as if everyone was just picking up on our raw defiance and three-chord rock – they weren’t getting the experimental side, the boundary-pushing side, the sense of possibility of the MC5. I never wanted anyone to do what I was doing; I wanted them to do what they were gonna do. You tell me your story your way, don’t tell me your story my way.

Since the early-‘00s, you’ve been active in maintaining the legacy of the MC5, starting with the DKT/MC5 reunion project [with drummer Dennis Thompson and bassist Michael Davis, who passed in 2012].

That was challenging. It was my great hope that Dennis and Michael could enjoy it and appreciate it. I hope they did but... by the end, they didn’t. And a lot of old resentments and feelings from 30, 40 years before were cropping up. It made it kind of hard.

Now you’re back with this upcoming MC50 tour. Do you feel an obligation to keep it going?

I started the band, and even though I could barely control it, it was my baby. In today’s world, the internet has made any band that ever existed, contemporary. Kids discover the Beatles as if they’re a new band. They discover the MC5 the same way. The MC5 exists right now. That’s something I never anticipated. At the time of Tyner’s death I certainly couldn’t have conceived of it. It’s good news that people want to come out and hear these songs and see this album played live 50 years on.

You just turned 70 and are raising a four-year old son. Does having a child in this stage of your life give you an added perspective?

Well, it's the coolest thing I ever did. I figure I’m just about done being a child, maybe I could look after one. (laughs) He’s bursting with enthusiasm for life every day and he’s great company. Margaret and I take parenting very seriously. We read up and consult with people, and try to do all the right things. Mainly, I want to give him love. Looking back, that’s why I didn’t destroy myself, even though so much of my behavior was so self-destructive. My own mother instilled enough love in me that even on my worst fucking day, I never woke up and said I hate living. I always woke up and said, Well, man, let’s see what today brings. Prison, addiction, crime, failure, Istill would wake up feeling pretty good about myself. Being loved, I think that makes a big difference – it makes all the difference.

This article originally appeared in MOJO 297.