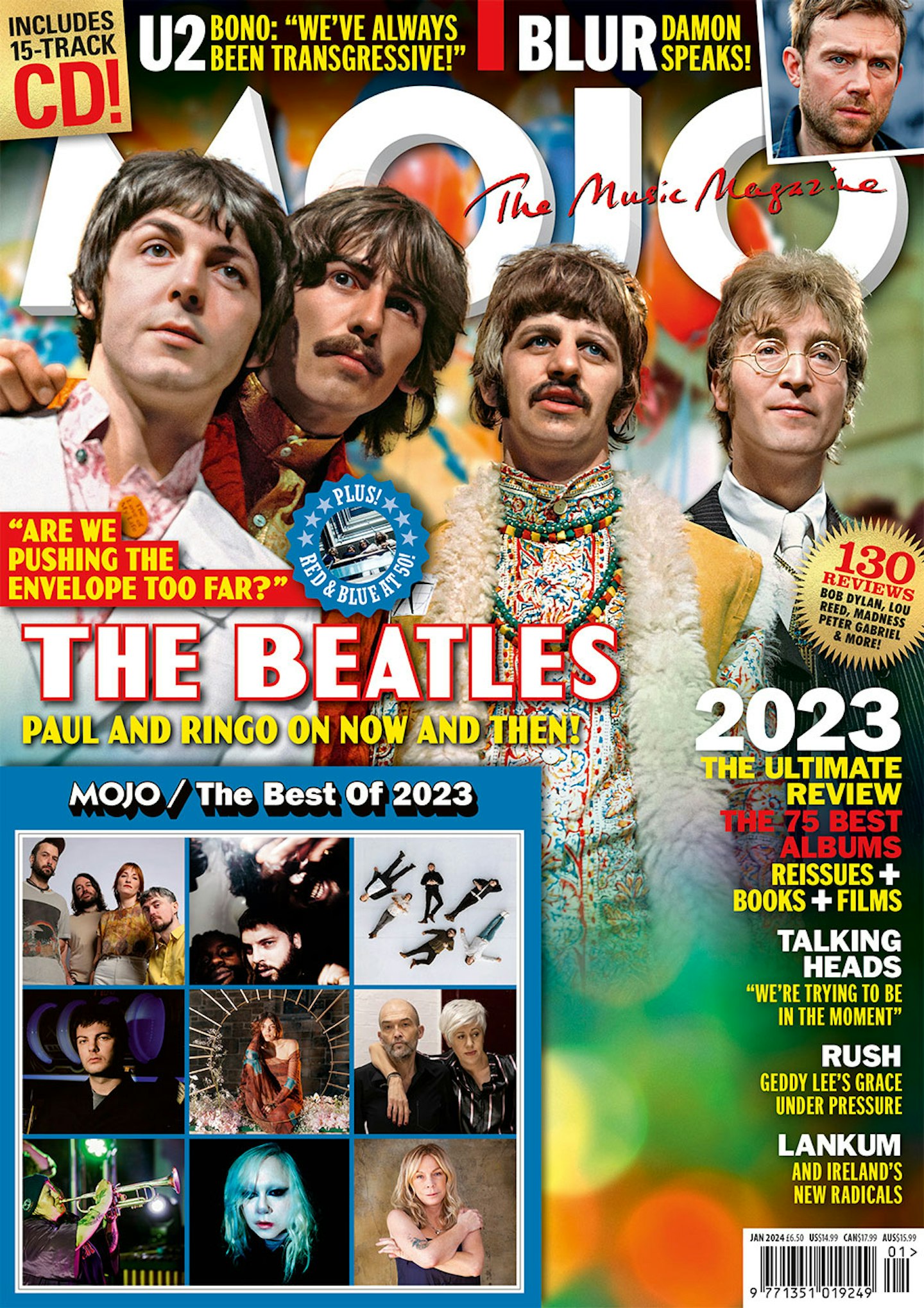

Picture: Angus McBean

BY THE END OF 1972 IT HAD already become clear to John Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr that they may have made a mistake hiring Allen Klein as their manager. Paul McCartney, of course, had come to that conclusion long before.

The individual Beatles were flying high in their solo careers, but with their contract due to end, dissatisfaction with Klein and his practices was coming to a head. Former London Records producer Allan Steckler, employed by Klein in 1969 to work with artists including The Rolling Stones and, after their acquisition by Klein, The Beatles, could sympathise.

“Working for Allen Klein had its benefits and its shit days,” states the 89-year-old music biz lifer, philosophically, from his New Jersey home. “Some days he could be the greatest person in the world. Most days he was the biggest asshole you ever met.”

With the Apple organisation that Klein still headed owing product to EMI and Capitol Records, but nothing in the pipeline, the pugnacious mogul called Steckler into his office. “Can you come up with something?” asked Klein.

In late 1971, with The Rolling Stones recently severed from Klein but their existing catalogue still controlled by the pipe chewing martinet, Steckler had been charged with the collation and packaging of Hot Rocks 1964-1971, quickly to prove an enormous and enduring success (it’s since clocked 12x platinum in the US). Unsurprisingly, Steckler suggested doing something similar with The Beatles.

“And The Beatles being The Beatles, one album turned out not to be enough,” says Steckler. “So I went to Klein and I told him that and he said, ‘Do two albums.’ So I did.”

I put that package together. And I never got credit for it.

Allan Steckler

Single-handed, or so he tells MOJO, Steckler compiled the tracks and chose the artwork. “I was in England months before,” he says, “and I came across the artwork for their proposed Get Back album. And I loved it. And so when I was putting these albums together, I remembered those photographs. And I said they would be perfect for this.”

Steckler pauses. He is a good-humoured fellow but when he continues it’s with an unmistakable pinch of Bronx pepper.

“I put that package together. And I never got credit for it. Because one of the things Allen Klein frowned upon was letting people take credit for what they’d done.”

KLEIN, THE BEATLES, AND MANY subsequent generations of music fans have had much to thank Steckler for. The Beatles 1962-1966, and The Beatles 1967-1970, released in April 1973 and thereafter known everywhere as the Red and the Blue albums, were instant smashes – Red flying to Number 3 in the UK and US albums charts; Blue peaking at Number 2 and Number 1 respectively – and bedded in as staples of the quartet’s catalogue.

The packages offered instant value, featuring among their 54 tracks Beatles singles that had never appeared on albums – at least, not in the UK – but also a compelling narrative. No pop group had travelled so far in such a short time. Angus McBean’s rhyming cover photographs – the Red’s an outtake from the cover shoot for the UK’s Please Please Me LP; the Blue’s initially intended for the shelved Get Back album – dramatised the transformation perfectly: a journey from innocence to experience and perhaps beyond.

Moreover, three years since the band’s demise it was a reminder of their greatness, perhaps a timely one as a new generation of pop-curious people came of age. As Beatles Kevin Howlett tells MOJO, “There were already kids of the generation below mine who were like, ‘Oh, so Paul McCartney of Wings had this other band…?’”

-

READ MORE: The Beatles' 10 most groundbreaking songs.

Compilation albums are commercial expediencies. The Red and Blue albums’ only official predecessor, A Collection Of Beatles Oldies, had been hacked together and bunged out by Parlophone in December 1966, The Beatles having nothing ready for the Christmas market. Dressed in prescient psychedelic garb, its fan-bait the twang some version of Larry Williams’ Bad Boy shouter previously unavailable in the UK (in the US it had been on Beatles VI), it feels pretty random even beyond the naff title. The idea that Paperback Writer, Eleanor Rigby and Yellow Submarine – massive songs from earlier in the year – somehow qualified as “Oldies” was either a now-bizarre attempt at irony or sincere testament to the supersonic speed of mid-’60s pop culture.

Today, it seems bizarre that when The Beatles called it a night in 1970 their labels’ immediate response was not a career-spanning compilation. But as Kevin Howlett notes, they weren’t sure how long the hiatus would last – hopefully, not long at all. So it fell to the bootleggers to make hay. In 1972 a New Jersey company called Audiotape Inc began marketing Alpha Omega, a 4-LP set (also available on 8-track cartridge) featuring 60 tracks, including a smattering of recent solo numbers, in mostly alphabetical order, and followed by two subsequent volumes, all brazenly TV and radio advertised in the US. Although believing themselves to be exploiting a loophole in federal copyright law, Audiotape were hit with a $15 million lawsuit by Klein and it seems they ceased and desisted. Given the timings and the legals, many histories assume Alpha Omega had a bearing on the conception of Red and Blue, but Steckler, whose memory seems sharp, demurs: “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

…Oldies, Alpha Omega and Red and Blue were all opportunistic responses to gaps in the market at the time they appeared. But it’s testament to Steckler’s work on the content and packaging that Red and Blue transcended their immediate purpose and continued to do so. Like Hot Rocks, Steckler notes, they’re not ‘Greatest Hits’ records pure and simple: “The idea was to show The Beatles’ evolution, from the beginning to the end.” And due to the role they’ve played in the lives of music fans, perhaps especially those currently in their fifties, and musicians including Noel Gallagher and Dave Grohl who have acknowledged their Red and Blue roots, they have become iconic. For Giles Martin, 54, whose family home did not, surprisingly, vibrate to the sound of Beatles LPs (his dad had presumably had enough of them), their impact was formative.

“I went on a school skiing trip,” he recalls. “And my closest mate had the double cassette of the Red and Blue albums. And that was my first introduction to early Beatles. So I knew these records really, really well. I knew the track order back to front.”

In terms of their perceived place in the canon, Martin puts it perfectly.

“For our generation they feel like proper Beatles albums,” he says. “The 1 album is a compilation, but the Red and Blue albums feel like The Beatles put them out.”

The expanded editions of the Red and Blue albums are out now: Amazon | Rough Trade | HMV

This article originally appeared in MOJO 362. More info HERE