With Brian Jones dead, Nixon in the White House and Woodstock eclipsed by the Manson murders, by November 1969 the hippie dream was over. The Rolling Stones’ last album of the decade captured the sense of dread magnificently. On the anniversary of its release, MOJO’s Mat Snow revisits Let It Bleed in all its ragged, hedonistic glory...

Rolling Stones fan Philip Larkin claimed that the ’60s really started to swing between the Lady Chatterley Trial and The Beatles’ first LP. Several years later, pundits were quick to identify the headstone for the decade: Let It Bleed by The Rolling Stones, released just a month before the end of the decade, and a week or so before Meredith Hunter was murdered by Hells Angels at the Stones’ free concert at Altamont.

With Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King assassinated and Nixon in the White House, Woodstock driven from the headlines by the Manson murders and Vietnam coming home as National Guardsmen opened fire on student protesters, a bad moon was rising over the Age Of Aquarius. Let It Bleed, cut without Brian Jones who’d been sacked from the group and then drowned in mysterious circumstances in July ’69, would be the soundtrack.

Yet one can listen to eight-ninths of the album without a single shiver of millennial angst. Such, though, is the enduring power of the opening Gimme Shelter that its aura irradiates every honky tonk lick that follows. Gimme Shelter is rock’s greatest song of dread, its trance-like pulse evoking a sense of ritual incantation. A thunderstorm presaged by the first raindrops of Keith Richards’ guitar and producer Jimmy Miller’s glissando percussion, it’s hard not to lose yourself in the seductive sway. That the song seldom works live is a measure of the fine balance of components that click on record, especially the duet of Richards’ wailing slide guitar and Merry Clayton’s deep soul cry.

Just as on Beggars Banquet, the hellfire fanfare of Sympathy For The Devil is succeeded by the plaintive blues of No Expectations, a cover of Robert Johnson’s Love In Vain dims the lights but for a single dramatic spot on Mick Jagger. Paralleling Beggars Banquet’s Dear Doctor, Let It Bleed’s next track, Country Honk – the single Honky Tonk Women played hoedown-style – shifts the mood from tragic to comic.

With the promising actress Marianne on his arm, Jagger was a frequent theatre-goer in 1968, inspiring his own thespian ambitions which reached their first and finest fruition in the Donald Cammell/Nicolas Roeg movie Performance, filmed that autumn. For the movie’s soundtrack, Mick flew the Stones’ keyboard player/arranger/buddy Jack Nitzsche over from Los Angeles. Nitzsche brought with him the former Rising Sons and Magic Band guitarist Ry Cooder. This young blues scholar was to play mandolin on Love In Vain and show Keith Richards the Sears Roebuck guitar tuning derived from ’20s country blues playing, in which, banjo-style, the bottom string was removed and the guitar was tuned to an open G.

I took Ry Cooder for all he was worth. His tuning, the fucking lot. I ripped him off.

Keith richards

Keith was transfixed. “I took him for all he was worth,” he told this writer in 1985. “His tuning, the fucking lot. I ripped him off.” From being an experimentalist, Richards became a devotee, those horny cock-crow riffs his trademark and the main stylistic difference between the ferociously outré Beggars Banquet as exemplified by Street Fighting Man, and Let It Bleed’s swaggering Americana, at its funkiest on Monkey Man (Charlie was really, really good that night).

The other by-product of Performance was that Mick had an affair with his co-star Anita Pallenberg, the reputedly witchy girlfriend who had bed-hopped from the unstrung Brian Jones into the more caring arms of Keith. Richards’ response to this on-set coupling was resentment, depression, an escape into snorting speedballs (heroin and cocaine) and, in his loneliness, making music.

“The important thing about Let It Bleed is the amount of work Keith did,” producer Jimmy Miller recalled. “When Brian died, Keith took over the musical leadership of the Stones, and did it brilliantly. I was afraid he’d overdo it. Then he’d suddenly just play something that would knock me out, some guitar fixure I’d never imagined which made the whole thing work.”

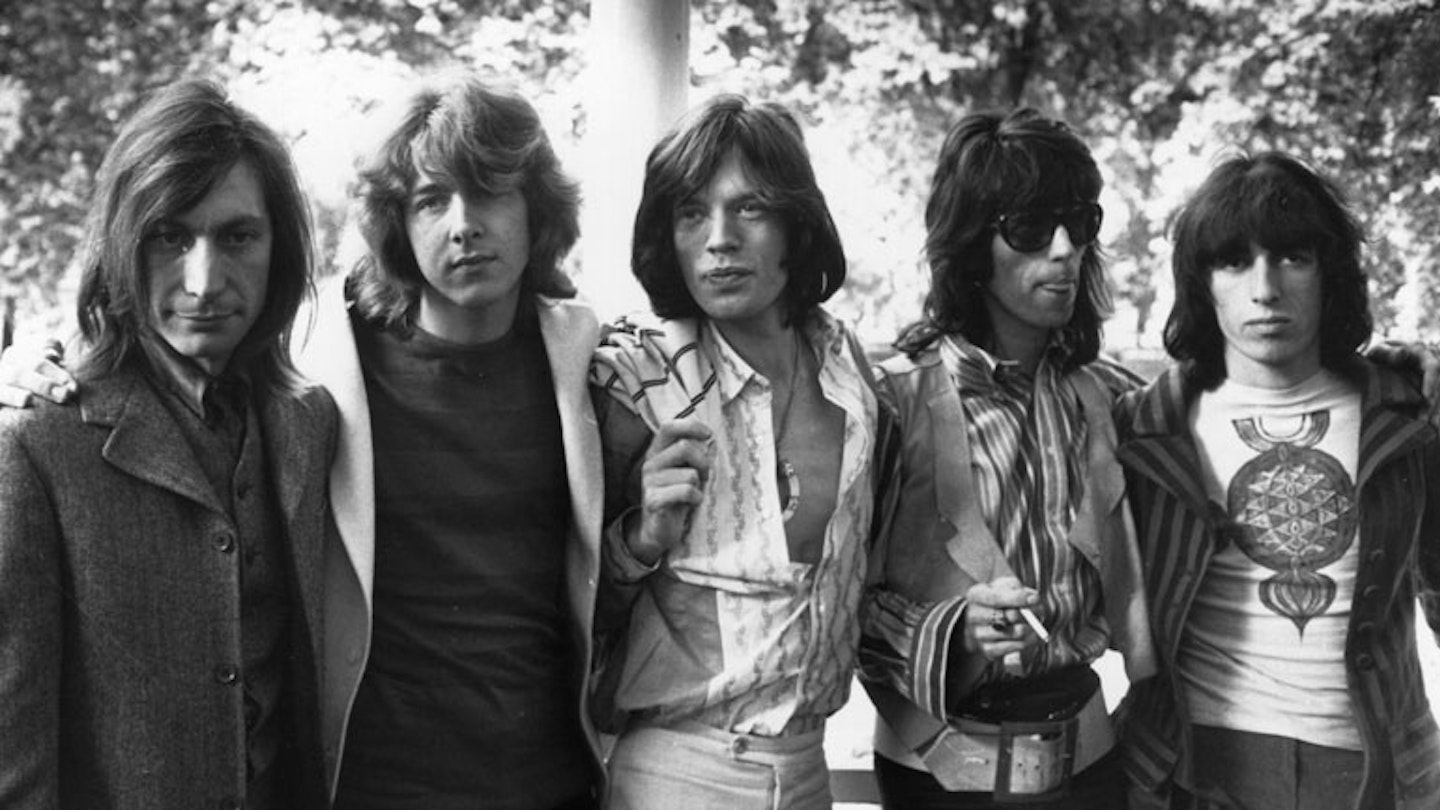

During Jagger and Richards’ writing of Let It Bleed (in England and on holiday in Brazil and Positano near Naples) and for almost all its making (in London and LA), Brian Jones was no more than nominally a Stone. He was fired towards the end of the recording and drowned on July 3. His replacement, Mick Taylor from John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, played one of the few British cameos on an album drawling and twanging with American accents, among them Leon Russell’s and Al Kooper’s.

Mick and Keith’s obsession with Americana had now spread from the Delta and Southside to the honky tonks thanks to another new American friend, Gram Parsons. He had met the Stones en route to play South African with The Byrds, quitting to stay with Keith when told of the segregated audiences the band would be performing to. Parsons introduced Keith to the music of country’s rebel spirits – George Jones, Merle Haggard, Jimmie Rodgers – and encouraged him to play piano.

The songs Country Honk (on which Nashville legend Byron Berline played fiddle), You Got The Silver (Keith’s first lead vocal) and the title track would have sat comfortably on The Gilded Palace Of Sin by Gram’s new band The Flying Burrito Brothers.

-

“A self-aware, historically mindful party” The Rolling Stones Hackney Diamonds reviewed

-

The Rolling Stones On Working With Paul McCartney: “Macca wanted to put the dirt on it.”

The Stones’ near-complete immersion in the roots America gene pool can be measured by what little remained of their anti-establishment Regency Buck phase. In Live With Me, the juke-joint sax solo by Delaney & Bonnie sideman Bobby Keys (his first of many appearances with the band) Americanises a song whose hilarious lyrics were calculated to wind up Disgusted of Tunbridge Wells. But the London Bach Choir’s massed voices provided a settling of Anglican respectability to be mocked by Jagger’s louche anti-moralising in You Can’t Always Get What You Want, the pay-off song whose resignation to taking the world as you find it rather than as you would wish it to be offers modest grounds for optimism.

“Get real” was not a message you’d expect or wish to hear from The Rolling Stones. Yet their blend of cynicism and hedonism chimed with an era that had lost its innocence. Even when they pooped the party, the Stones were indeed the Greatest Rock’n’Roll Band In The World.