Picture: Kevin Cumins

In 1994 Suede were British pop saviours, poised for greatness. But sex, paranoia and an epic Orwellian concept album about drugs, porn and madness soon put paid to that. On the 30thanniversary of its release, MOJO’s Martin Aston looks back at the “monumental fuck-up” of Dog Man Star.

At the end of 1993, after Suede’s first tour of America, their frontman, Brett Anderson, changed his answerphone message. Gone was David Bowie’s 1969 acoustic ramble, Letter To Hermione, replaced by dialogue from Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s 1970 psychosexual gangland saga, Performance, Mick Jagger’s voice intoning, “The only performance that makes it, that makes it all the way, is the one that achieves madness.”

“I used to watch Performance every day,” Anderson says today. “I was very into the idea of musician-as-magus, a powerful, mystical lunatic running around. That’s how I saw myself.”

Yet the lunacy that filled the spring and summer of 1994, as Suede toiled to emulate the success of their self-titled 1993 debut (the fastest-selling UK album debut since Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s Welcome To The Pleasuredrome in 1984), did not quite produce the result Anderson imagined. With its tortured torch ballads, highly wrought rockers and labyrinthine epics embellished by 40-piece orchestra, Suede’s second album, should have established them as an unassailable musical force. Instead, with the band’s guitar prodigy Bernard Butler recording by day and singer/lyricist Anderson only singing at night – “like Nosferatu, rising from his coffin” – the album, Dog Man Star, became a site of creative chaos that would lead to furious arguments, mental torture, and death threats, that dismantled one of the most powerful creative partnerships in British music. “It was all a monumental fuck-up,” says Butler today.

In an early ’90s indie scene dominated by grunge, shoegazing and Madchester, Suede’s embryonic indie-dance made little impact. Formed in 1989 by Anderson, the same year his mother died of cancer, Suede Mk1 comprised Brett’s then girlfriend, Justine Frischmann, his teenage best friend Mat Osman, and the 19-year-old Butler, found via a Melody Maker ad that October. The drum machine that powered early shows was replaced in 1991 by Warwickshire-born Simon Gilbert. But after Frischmann left (she soon formed Elastica), the core four re-imagined themselves as louche, glam-tipped rockers, holding a torch for classic British guitar pop. Melody Maker’s “Best New Band in Britain” cover of April 25, 1992 validated the transition and Suede’s second and third singles, the slovenly, stomping Metal Mickey and the illicit electric declamation of Animal Nitrate went Top 20 and 10 respectively. Butler’s fluid, piercing riffs tied to Anderson’s lyrical hooks and provocative agenda (Animal Nitrate, like first single The Drowners, had an undertow of gay sex) suggested a band that could reach the same parts and inspire the same loyalties as The Smiths. Hysterical crowd reactions at shows throughout 1992 and 1993 agreed.

Sitting in the attic room of his Notting Hill house, mere streets from where Performance was filmed, Anderson, looksback on the rush and chaos of that era with mixed emotions: Pride first, then regret. “The kind of media exposure we had meant people didn’t like us without even seeing us,” he says. “But the whole point of Suede was to provoke a reaction. It was really exciting, not some grey, little boring life but the one I’d always wanted. And the things I wanted to write about – a threatening sexuality, darkness, sadness – well, no one else was doing that.”

Brett’s home is a long way from Hayward’s Heath in Sussex, the “suburban grave” he grew up in, which fuelled him – alongside his Sex Pistols and Crass records – with the impetus to escape. By 1988, he was embracing a new world of studies (Town and Country Planning!), love and dreams of stardom. But the shyer, prickly Butler, born to an Irish-Catholic family in London’s East End and working as a clerk in London’s West End, felt like an outsider right from the start. “Brett, Justine and Mat were posh middle-class kids to me,” he says, sitting on a sofa in Edwyn Collins’ London studio, a space he rents in his current job as a producer. “I was from a different background. They asked me for my favourite book and film, and I didn’t have one. I remember asking, ‘What’s androgyny?’ It wasn’t my world.”

Instead, the two bonded over music, especially The Smiths and Bowie, with Butler using his guitar skills to craft Ziggy-type drama for Anderson’s tales. “I desperately wanted to impress him,” Butler recalls. “I wanted him to become my Morrissey.” Once Frischmann left, the two moved closer creatively. “That’s where those early Suede songs came from,” Butler says. But once Suede started to appear on magazine covers (19 before the debut album came out), Anderson started to slip away. “The more people wrote about Brett, the more he seemed to want to shape his life around that image,” says Butler. “He took loads of drugs, and shagged everyone he could. I had my cosy little life with my girlfriend – now my wife – and we saw each other less.”

'[There was] huge bags of coke, piles of dollars and contracts strewn across the floor…'

Simon Gilbert

When Suede first toured America in 1993, Butler’s father had just been diagnosed with an advanced stage of cancer. Arriving in Los Angeles on June 11, drummer Gilbert recalls, “huge bags of coke, piles of dollars and contracts strewn across the floor, Evan Dando, Rodney Bingenheimer and Rastas in hats.” Butler stayed in his hotel room, furiously writing, just as he’d done at home, “every single day for 18 months.”

A stopgap single, Stay Together, in February 1994 was titled with perfect irony – it was built on growing tensions between Butler and Anderson. “We wanted something a lot stranger,” the latter notes, “out on our own tangent.” His lyric was inspired by vivid childhood fears of nuclear war while Butler conceived a tumultuous and multi-tiered ballad lasting over seven minutes. “I was desperate to do something emotional and strung out,” says Butler, who admits he was constantly stoned on weed during that period. “I’d seen all these tragic characters around the band, and I felt the world had become a nasty place. Brett had retreated. Probably because of what happened to his mum, he didn’t want to connect to me.”

“I didn’t have the emotional tools to console Bernard when his father died,” says Anderson. “Our relationship had broken down to such an extent that I was frightened of engaging with Bernard in case it damaged the relationship further.” Instead, Anderson became a passive bystander.

Butler’s father died in September 1993, during the recording of Stay Together. Eleven days later, Suede returned to America, co-headlining with The Cranberries, who’d sold 300,000 albums in the US with a more palatably sweet sound. The Irish band were on first but kept drawing the bigger crowds. In Atlanta, Suede were forced to go on first. “We were seen as doomed failures,” Butler admits. By then he was travelling on The Cranberries’ tour bus, not seeing his bandmates until stage time. They cut the tour short and returned home.

“Suede was a very British band,” says Osman. “You didn’t talk about feelings. You fought and made up through the songs. It was about control of the band and the idea of the band. The last show we played, in New York, was violent and insane, with Brett and Bernard upstaging each other. Proper theatre.”

As Anderson’s best mate and, for six months, Butler’s flatmate, Osman watched the drama unfold. “I thought that if Bernard wasn’t around us on that tour, things might work out. I can’t believe our naivety. But I couldn’t comprehend his attitude. You’re doing the greatest thing a human being can; you’ve made an incredibly successful debut album, the world is waiting for your next record…”

That record wasn’t only inspired by Anderson’s ambition but also by the movement Suede had unwittingly kickstarted – Britpop. “I was desperately embarrassed by flag-waving,” says Butler.

“To see Suede as jingoistic was completely misreading us,” says Anderson. “We’d never moved with the herd.”

In addition, Frischmann was now dating the frontman of the band’s arch-enemies, Blur’s Damon Albarn. “After three years of no one wanting us in their club,” says Osman, “it was time to say, no one can join our club and make a record that set us aside from our peers.”

Anderson moved from West London, which he now associated with “this horrible, trendy Britpop scene”. He ended up in the garden flat of a sprawling gothic edifice in Highgate, the north London HQ for Christian sect, the Mennonites: “That amplified the strangeness. But they were remarkably tolerant. I was either playing insanely loud music or completely off my head.”

Osman recalls evenings, “wrecked at each other’s houses, listening to records. We were listening to Pink Floyd and Kate Bush’s Hounds Of Love, especially side two. The songs flowed into each other and a story runs through it. The greatest thing we could do would be the same.”

Anderson had discovered Scott Walker, as had Butler, who says he was also consumed by Joy Division’s Closer, The Smiths’ The Queen is Dead, Marc And The Mambas’ Torment And Toreros and The Righteous Brothers’ You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’. “The most highly-strung kinds of music,” says Butler.

The two were still not talking, however, so demos were swapped via post or third parties. “I was looking for something with depth and gravity,” says Anderson. “The first album was my reality up ’til then. But touring exposed me to a broader world that I wanted to write about. Dog Man Star is about that ambition.” The album title (inspired by Stan Brakhage’s ’60s film Dog Star Man) was, says Anderson, a slogan for empowerment, “dragging myself from a council estate in Hayward’s Heath… an anthem to meritocracy.”

For the first track, Anderson conceived a Sgt. Pepper/Diamond Dogs-style prelude, Introducing The Band. “I’d heard this amazing chanting in this Buddhist temple in Kyoto that I wanted to approximate. The crushing, metallic drone to Bernard’s music reminded me of that phrase from Orwell’s 1984, ‘If you want a vision of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face forever,’ so I wrote a fantasy about the unstoppable force a band could become.”

Anderson admits he was taking large amounts of Ecstasy at this point. The very first line of Introducing The Band runs, “Dog man star took a suck on a pill...” The singer was enjoying his Turneresque slide into debauchery, but, like Turner, was no stranger to isolation and paranoia. “Brett was obsessed with being acknowledged and successful, but Bernard was the chink in his armour,” band PR Phill Savidge thinks. “Oasis had begun selling loads, and Brett saw his throne usurped, and was concerned that without that songwriting partnership, what was there? I think he was scared.”

Future single We Are The Pigs, written by Anderson in comedown mode, described, “a cloud of fear I saw over life, realising this grotesque house of cards we’d built could come tumbling down.” Another track, Heroine, was, according to Anderson not about smack but, “pornography and being unable to form relationships.” The 2 Of Us and Still Life were further odes to isolation, starring the “housewives on Valium” eulogised on the first album.

Immersed in lyric writing, Anderson spent hours in Highgate library, looking through biographies of old film stars. James Dean’s car crash inspired Daddy’s Speeding, while snarling rocker This Holly-wood Life applied the casting couch syndrome to the seedier side of the music business. Named after the Brando film, The Wild Ones was inspired by Anderson’s then girlfriend, 17-year-old Anick. “Our relationship was fiery and fractured,” he says, “the kind you have when you’re young.” Their relationship also fed into the album’s nine-minute centrepiece The Asphalt World, whose lyric referenced Anick’s female lover. “I wasn’t interested in monogamy at that point,” says Anderson. “Sexual jealousy can be a stimulant too.”

Before the March ’94 album sessions, four live dates were booked to promote Stay Together. A bootleg from Blackpool’s Tower Ballroom on February 11, 1994, reveals a band feeding off the violent energy of the Anderson-Butler relationship. But the next night’s show, at Queens Hall, Edinburgh, proved to be Butler’s live Suede swansong.

“It started off amazingly,” Anderson recalls, “and then suddenly Bernard had technical problems and we totally lost our momentum. I was frustrated. I suspected he was deliberately sabotaging the gig. It was all such a shame.”

Suede took this mood of profound resentment into north-west London studio Master Rock, working with Ed Buller, who’d produced the first album. “I said to [co-producer] Flood beforehand, I’ve a horrible feeling they’ll split up making this record,” Buller recalls. “Flood replied, ‘It’ll probably be a great record then.’ He’d been there before, with bands like Depeche Mode.”

Butler and Gilbert recorded all the backing tracks. The fighting had already begun. “I’d be directing Simon,” Butler explains. “A fill here or roll there, referring to [Blondie’s] Clem Burke, who we both liked. But he got increasingly pissed off at me telling him what to do. I thought I was doing the right thing. I was obsessed.”

“I only remember one time when Bernard ‘asked me’ to play something,” says Gilbert. “It didn’t happen again! It’s been said I threw my drums at him down the stairs, but I actually threw my sticks at his favourite red guitar – I always handled my anger by destroying things. I think we understood each other after that.”

Buller recalls Butler resisted interference. The biggest stumbling block was The Asphalt World, 18 minutes long in demo form. Butler maintains he always intended to whittle it down but Buller remembers otherwise. “I told him the guitar solo was too long. ‘No it’s not.’ Let’s just try. It took over three weeks to get it the right length.”

Buller says the final straw was Butler giving a rare interview to Vox magazine at the end of May in which the guitarist raged, “I’m desperate to do things outside of Suede. Brett’s so fucking slow, it’s driving me insane.” That night, Anderson recorded his vocal for The Asphalt World: “I took all of the pain I was feeling and channelled it into my delivery,” he says. “Bernard later apologised, but it wasn’t nice.”

A summit meeting in the studio, where Anderson pleaded that they channel their energy into work was only a brief ceasefire. Butler went AWOL for two weeks before issuing an ultimatum: either Ed Buller was sacked or the guitarist himself would walk. “Being an arrogant little shit,” Butler says, “I thought I could say, Ed’s out of order, let’s get someone else to mix the album. I made a really childish stand-off, to see how much they really wanted me, and I deserved everything I got.”

“Why did I choose Ed over Bernard?,” says Brett. “It wasn’t that simple. It was about being pushed into that decision. Where would Bernard’s demands end?”

“Bernard wanted out, that was clear,” says Osman. “And you don’t want to be in a band if someone feels like that. I think he was always going to be unhappy in Suede.”

Anderson agrees. “I was documenting a lifestyle Bernard didn’t want to be part of, the fringes of society, people who took lots of drugs and had casual sex. That was the world I saw around me. To change that to reflect Bernard’s sensitivities would have been dishonest. I wanted to push it as far as it would go. ‘The only performance that makes it…’ etc. That’s why I didn’t do everything in my power to make him stay. Which I massively regret now.”

Gilbert’s diary reveals June 14, 1994 as the last day he saw Butler. By the month’s end, under legal obligation, Butler was completing overdubs in another studio and sending over tapes with veiled threats (“I’m going to kill you!”) whispered through his guitar pick-ups. On July 8, he officially left Suede. With session horn players in that day, all present performed an impromptu version of The Girl From Ipanema. “My major memory was relief,” recalls Osman.

Post-Butler, The Wild Ones was given a shorter coda. The original seven-minute version is available on the new 30th Anniversary Edition of Dog Man Star, alongside a 12-minute version of The Asphalt World. In both cases, the decision to, “drag things back from Bernard,” feels justified. However, Buller admits Butler was right about the production: “I had to go to America to learn how to do bottom end,” he admits. “Anything that falls into the category of over-production was me!”

On September 12, 1994, Dog Man Star’s lead single, the stomping, intense We Are The Pigs, was released. “It summed up the album’s paranoid, tortured, neurotic, violent side in a way that New Generation, which Sony wanted, didn’t,” maintains Anderson. The single peaked at 18. Stay Together had made Top 3. Dog Man Star briefly topped the charts but was knocked off by the Oasis debut, Definitely Maybe.

'The idea of us as Byronic opium-smoking fops was a dead end.'

Mat Osman

However, Suede survived. Richard Oakes, a 17-year-old fan, replaced Butler and began to write songs, as did Anderson and new keyboard recruit (and Gilbert’s cousin) Neil Codling. The resulting, poppier Coming Up sold a million, but later albums were derailed by Anderson’s drug intake and diminishing quality control. It took the band years to view Dog Man Star as anything but an albatross around their necks.

“We disowned Dog Man Star for ages,” says Osman. “One show in Germany, I saw a ‘Coming Up is going down’ banner. Fans felt betrayed. We’d made this shiny pop record instead of something brooding and gothic… but the idea of us as Byronic opium-smoking fops – which we’d played up to – was a dead end. I wanted that part of my life locked up and left.”

“I’d have to be in a strange mood to listen to Dog Man Star now,” says Anderson. “I love it but the tension makes me restless and I’m sad, too, wondering what we’d have done if Bernard had stayed. It’s like seeing the picture of someone that you love, who then died.”

“My twenties were a nightmare,” says Butler, “so Dog Man Star is not a comfortable, pleasurable listen for me. But it’s still fantastic.”

In September 2003, after Anderson decided to fold Suede, the band performed all five albums in their entirety over five nights. A week later, Anderson called Butler. They decided to work together, recording an album as The Tears. But Dog Man Star wouldn’t let go. The Oakes-model Suede played it again in May 2010, a year after their Teenage Cancer Trust reunion at the Royal Albert Hall.

Anderson admits it felt “slightly unprincipled” to play Dog Man Star without the original line-up. “Part of me would love to play those songs with Bernard again,” he says, “but a part knows it probably won’t ever happen. Anyway, it’s too complex, emotionally, to orchestrate. And Bernard hates the idea of reunions.”

“It’s not on the cards,” says Butler. “I’ve always told Johnny [Marr], Don’t reform The Smiths. Morrissey would do it at the drop of a hat, and he’d have Rick and Bruce, as he calls them, in cages at the back.”

Revisiting Dog Man Star has clearly affected Anderson. Two days after we meet, he sends a lengthy e-mail in which he says: “It was my cowardice that led to the split… if I’d had the guts to just pick up the phone the inevitable fracture could have been avoided… but drugs, managers, press distortion, a soul-sapping US tour, money, celebrity etc [meant] we were both unable to see beyond the mental caricatures we’d drawn of each other.”

Thirty years after its release, what happened on Dog Man Star still hurts. It is, says Anderson, “Still too raw for me and Bernard to sit down together and talk about what happened.”

This article originally appeared in MOJO 211. Dog Man Star 30th Anniversary Edition is out now on Demon.

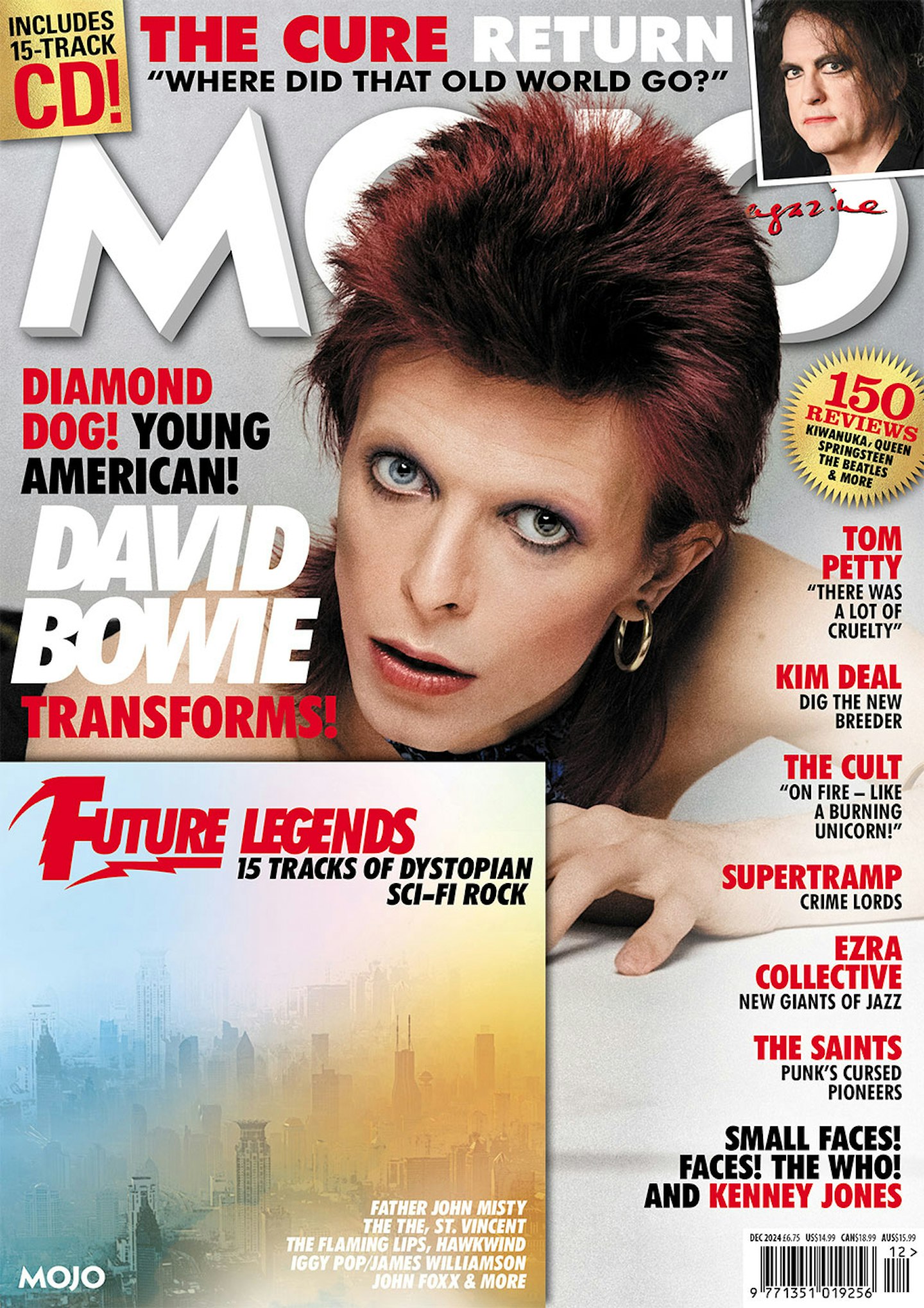

Diamond Dog! Young American! David Bowie Transforms! Get the latest MOJO to read the full story of David Bowie's unbelievable 1974 metamorphosis. Also in the issue, The Cure's new album unveiled, Queen reviewed, Tom Petty's crisis year remembered, Supertramp’s Crime Of The Century retried, the Small Faces, Faces and The Who relived by Kenney Jones, King Crimson, Tina Turner and much, much more. More information and to order a copy HERE!