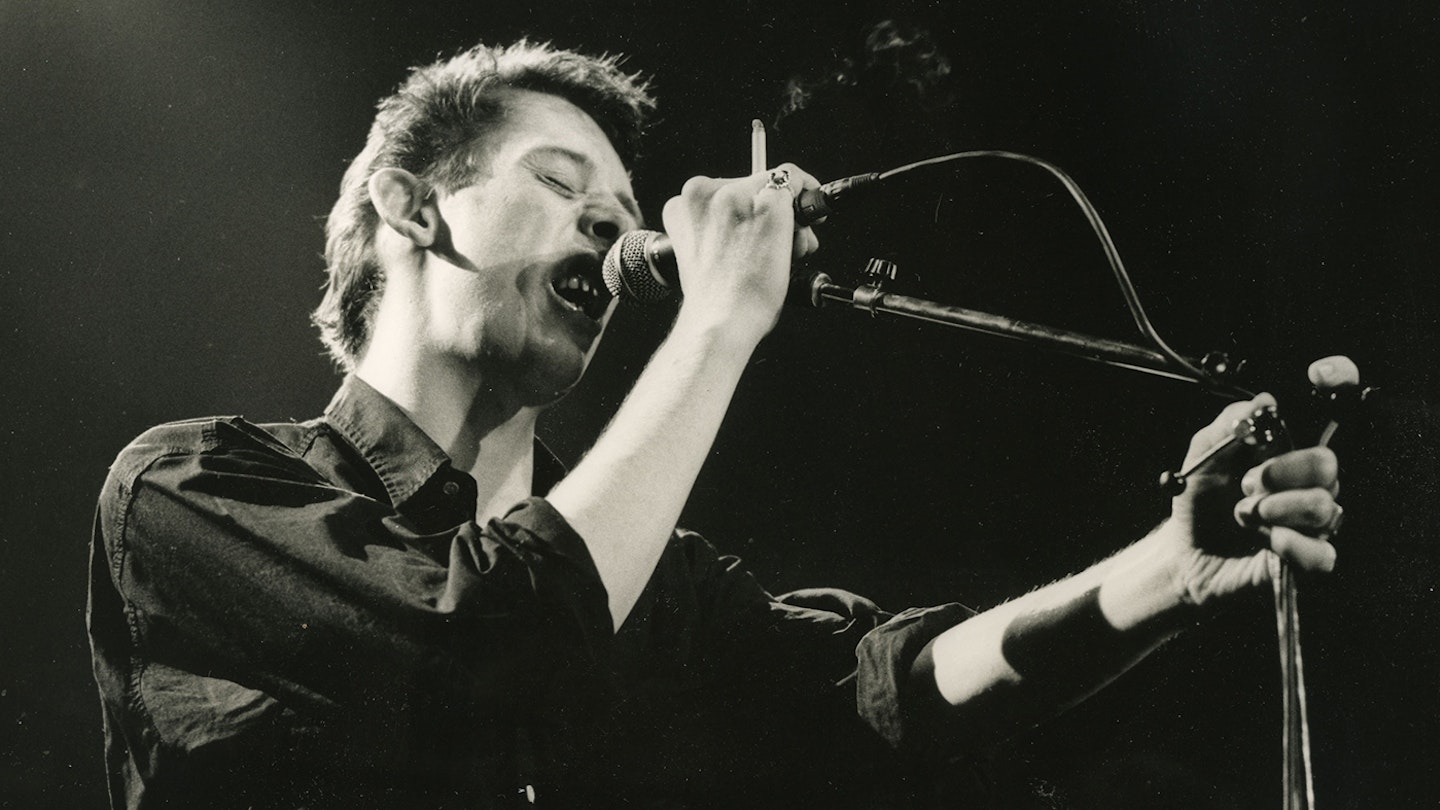

Shane MacGowan, singer-songwriter and leader of The Pogues sadly passed away in 2023, aged 65. In tribute to MacGowan, MOJO revisits our 2010 encounter with the legendary songwriter. After a wild goose chase around London, Liverpool and Dublin, MOJO’s Will Hodgkinson finally sat down in the wee small hours at MacGowan’s home in Tipperary. On the agenda: Irish nationalism, faith, the meaning of life, MacGowan’s unique cure for baldness and a 6am trip the “fairy fort” at the bottom of the singer's garden...

While you wouldn’t expect an interview with Shane MacGowan to be straightforward, nothing quite prepares you for the actual experience — when it finally happens. Various attempts to meet up with MacGowan in London come to nothing. When Paul McGuinness, the muscle-bound, ex-jailbird, thoroughly charming leader of MacGowan’s second band The Popes gets on board, things look more hopeful. A time is set —11pm, the night before MacGowan is performing with The Pogues in London — and a failsafe venue found: the bar of the hotel he is staying in. But half an hour before we’re due to start a call comes from McGuinness. MacGowan is in Liverpool. He hasn’t quite managed to get into the tour bus yet.

If the mountain won’t come to Muhammad, there’s only one thing for it: to meet MacGowan in Dublin, where he shares a house in the smart residential neighbourhood of Donnybrook with his girlfriend, the writer Victoria Mary Clarke. But on arrival in Dublin on a Monday afternoon, the ever-patient McGuinness announces that MacGowan wants to meet at Philly Ryan’s, his favourite pub — in Nenagh, Tipperary, which is four hours’ drive away.

We enter the door of Philly O’ Ryans, a womb-like living room of a pub, at 8pm. MacGowan is at the bar, pale, bloated and smiling, pulling out fistfuls of crumpled notes from his pockets and buying rounds. He has a shock of upright hair and a permanently surprised expression, as if amazed at the mind-altering effects alcohol can have. An unending flow of regulars crowd around MacGowan, variously wishing to sing with him, sing for him, tell him a story and buy him a drink. “He’s certainly a gentleman, whatever that is,” says an old man by the bar, as a biker with an accordion squeezes out a rendition of Fairytale Of New York. MacGowan leans into his spot at the bar, a cider and ice, a triple vodka, a whisky and Canadian Club and a mug of an unidentified but probably alcoholic liquid before him.

MacGowan is nothing less than a living saint in County Tipperary, where he grew up when his family wasn’t undergoing one of its periodic moves to southeast England. It seems only a matter of time before he’s honoured with a statue in Nenagh’s town square, which will serve as a resting place and occasional convenience for visiting toucans. It’s impossible to get him alone. Finally, at 2pm, the bar shuts. Paul McGuinness suggests we do the interview back at MacGowan’s stone cottage, deep in the Tipperary countryside, which has been in the family for 200 years. MacGowan seems obliging. The only problem is that he insists whoever is left in the pub join us. And it takes him half an hour to get from the door of Philly O’Ryans into the taxi waiting outside, which is exactly two and a half feet away. “Time slows down around Shane,” explains McGuinness.

The cottage is a traditional Irish byre dwelling, featuring a main room with an open hearth, an outside toilet, and two smaller rooms that were once used for housing animals. Today humans and animals in Tipperary live separately. This will come as a huge relief for any nearby pigs and cows. Bottles and glasses, many of them broken, cover the long table at the centre of the room alongside ashtrays, teabags and scraps of food. A television hums in the background. A wooden cross hangs on the uneven wall over the hearth. The cottage is cosy, but phenomenally chaotic.

MacGowan is a genial host and a reluctant interview. He loves to talk — just not about himself. His laugh sounds like a lawnmower running over a stone. We get the tape rolling at around four in the morning, with McGuinness doing everything in his power to encourage MacGowan to answer questions and to stop the two other drunken Irishmen in the room from singing and shouting. And there’s another problem. In May 2009 Shane MacGowan travelled to Spain to have a set of false teeth fitted. Tonight, he appears to have forgotten to put them in.

I’d like to start by asking how you’re feeling about your place in music today. You’re getting back with The Pogues, you’re working occasionally with The Popes… are you ready to play an active role in being in bands and writing songs once more?

[Interrupting as he watches a television debate about Ireland’s economic situation] Can we watch this for a minute, yeah? This is the political background, yeah? Yes, this is serious. There are a lot of property developers that have gone bust. But we’re not getting surveillance all the time in Ireland like you do in England. There are about 60 cameras on the main roads over there, yeah?

Are you living here in County Tipperary now?

Yes, I’m spending most of my time here, and it’s only a short spell up to Dublin. Donnybrook used to be a really pukka area — you’ve heard of Dublin 4, haven’t you?

How are you feeling about writing songs at the moment?

[Getting agitated] Look, tonight was a Monday night in the lounge of Philly’s and there was an accordion player, right? He wasn’t on his best form but that was just a typical Monday night. Tipperary was never a cut off place. That’s my sister’s Jesus And Mary Chain album right there, which she bought in the fucking town when it came out in nineteen eighty whatever it is.

Paul McGuinness [after MacGowan falls into silence and watches television]: As long as I’ve known Shane, most of his inspiration comes back to his roots. A lot of people don’t want to take the music out of Tipperary. Shane sucks it all up and gets it out there.

Would you be listening to The Jesus And Mary Chain concurrently with, say, a traditional singer like Joe Heaney? Would these be the things that fed into your own vision?

Of course! And there was John Coltrane, and what they call heavy blues. These are young bands, a lot of American bands and some European, and it’s what I call 1970 rock. It’s psychedelic, it’s heavy, it’s mad, it’s crazy, and it has an acoustic side to it too. There were no clear lines. We were skinheads for a while, and then we became freaks and listened to Hawkwind. It was a natural progression. Ireland goes round and round. It’s a circular tree. It’s one big acid house.

Wouldn’t you have to go to Dublin to discover the counterculture?

Out here in the country, right, people have been wise to drugs and stuff for hundreds of years. They take magic mushrooms. Marijuana grows wild here. People have been cultivating it for as long as forever. We were an alternative society. The whole community was an alternative society!

Was your family part of this alternative society?

Fuck, yeah! If you think I’m… you should meet my mum and dad. My mum’s 80 but she don’t look or act it. My dad’s getting… what’s the word? Odd. And there’s my uncle Sean. He was a rocker, into motorbikes and all that. When rock’n’roll was dying everywhere in the early 60s we were rocking on in Ireland. There was a lot of immigration over to England and people were bringing the records back. Actually, we were ahead of the game in the Swinging Sixties. The farmers would play the latest records to milk the cows to. You get a bigger yield that way.

Did you feel much connection with England?

We never followed England. Our influences were American. We didn’t get Top Of The Pops over here. We weren’t connected to England at all.

But you have grew up in England intermittently. You were even at London’s Westminster School for a brief period.

Yeah, but what it really came down to was hip music. If it was English or American or Irish it didn’t matter. Hip is not the same as cool. Hip is always hip, you know what I mean? We had show bands over here in the 50s that picked up hot American R&B records and learnt to play them. The Irish charts were a mixture of every kind of style. Then [folk rock pioneers] Sweeney’s Men came along in 1965 and sounded like The Pogues. Their second album in late 66 was bloomin’ psychedelic. Amazing band… There was a massive influence from Sweeney’s Men on us. People forget that Phil Lynott, Rory Gallagher and Taste were doing things here way before anywhere else, yeah? They were all from the same area. Yeah? Yeah? Yeah? And by the 70s, let’s face it, music was getting pretty uncool everywhere. The show bands were kind of creaking a bit by then.

Did you have a clear idea for what you wanted with The Pogues, and later The Popes?

When The Pogues started the only philosophy was: anything goes. But Irish music is world music. You can hear it in Jamaica. Reggae and all that. You know what I mean? It’s not a generalisation to say that when the West Indies broke free from England the West Indians said: ‘what the fuck are we doing, working for the English, slaving for these people, yeah?’ They’re into dancing and drinking and partying and the whole thing, so they’ve got more in common with the Irish than they have with the English. West Indians have got the similar culture to us, the positive and negative things – the guns and the Rastafarianism and all that.

How did The Pogues go down in Ireland? Your raucous take on traditional music must have ruffled a few feathers.

[Irish language poet] Seán O’Riordáin started it, slinging out all these rules in a column in The Irish Times that had been decided on by the musical mind police people. The folk music was destroyed all over Ireland as a result.

There does seem to be a looser, more rebellious tradition that you are a part of. Alongside The Dubliners there was Eddie and Finbar Furey…

The mind police set up rules for music and the Fureys broke all that down. They broke every bloody rule. Finbar Furey was the first born to an old travelling family. His father, Ted Furey, was a famous fiddle player. There were loads of travelling musicians and bards and all that all over Ireland. The real point is that we’re all in this shit together, yeah? Unless you’re a landowner or a particularly spineless bastard you’re a part of this stream of thought that includes people like Yates and Joyce and Finbar Furey and fucking, you know… they all agreed on one thing: that we should decide what went on here, that the Irish people should decide.

When did you first make an impact in Ireland? The Pogues came over here and appeared on The Late Late Show…

That goes to a cross-section of the community. Everybody stayed in on Saturday night to watch it. It was the highest show in the land.

What did you perform? The Sick Bed Of Cúchulainn?

People around here saw it and they knew what we were doing.

Didn’t the concertina player Noel Hill call The Pogues “an abortion of Irish music?”

Noel Hill had a radio show and all kinds of stuff. In the 60s he worked for Zeppelin, the Stones, The Beatles. The summer of love happened in Ireland, yeah? It happened earlier, probably, at fairs all over the country. And we were smart. Everybody in Ireland, even if they’re dumb, is smart. You know what I mean? In the 60s it was the civil rights thing all over the world and we were connected with that. We weren’t hiding in bushes or anything, but the point was that there was terrorism coming in at the early 60s and things changed very quickly. Not in a bad way, yeah? We weren’t an African tribe, yeah? Our peacekeeping forces have been out in the Congo and that’s just one example. It was the people that are fitting up surveillance all over England at the moment that exploited the situation. There was a lot of Orange Lodges that started making lots of noise. Nobody was expecting or wanting what happened at the end of the 60s, but it wasn’t much fun for anyone at the end of the 60s. It went to fuck everywhere.

I think what you’re saying is that Ireland in the 60s was a more sophisticated place than is generally perceived.

There was constant free speech and dialogue. The citizens of Derry, backed up by everyone in Ireland, refused to allow the Royal Ulster Constabulary to quash their right to protest. (This led to the killing of 13 unarmed civilians by British Paratroopers in 1972 called Bloody Sunday). From then on the RUC told the people in England one thing (about the Troubles), but they couldn’t tell the people in Ireland that what was going on wasn’t going on. And because we were all over the world the word got out.

[Tom Creagh sings more rebel songs. An argument breaks out when he sings a song about taking his place in Heaven next to Bobby Sands and Shane Macgowan, understandably so given that MacGowan is still very much on Earth.]

MacGowan: The greatest comrades of the Irish republican movement were the English working people, the miners and so on. And of course all that goes into what we did with The Pogues. It goes into what anyone anywhere does. We’re entertainers first and foremost, yeah? And we’ll sing rebel songs, love songs, and the songs of Finbar Furey, who broke the mould at 17 years of age when he won a piping competition. The English people as a general rule, yeah? They were the ones that had the wool pulled over their eyes by the Unionists in England. The Unionists were holding onto an England that had crumbled all around them.

Do you see yourself as part of the tradition of Irish genius madmen, like Brendan Behan and WB Yeats?

[Ignoring the question] When we came over here as a band Noel Hill just happened to be a guy that disagreed violently with what we did. We didn’t mind. Noel Hill has every right to his opinions, yeah? We’d already had all this bollocks from the BBC who thought we were rubbish.

What happened with the BBC? Pogue Mahone (Gaelic slang for “kiss my arse”) is a very soft insult, the sort of thing your mother teaches you.

The BBC found out because an Irish lorry driver rang up John Peel when we were doing a session and asked him if he knew what Pogue Mahone means. When Peel found out, he announced it on the radio. And when the old guard got wind of this, they felt that one lot had just had a massive hit, and that’s Frankie Goes To Hollywood, and they couldn’t let it happen again. They tried to ban Relax but it was too late, so they thought they’d better ban us. But people were calling us The Pogues anyway by then so the BBC said: “we won’t ban you. We’ll just pretend you don’t exist.” They actually did ban The Dubliners years before.

In other words, there was an attempt at censorship that failed.

Well, they tried. But it’s always been like that, with these people that put surveillance cameras everywhere. They tried to get The Rolling Stones out of the way, but they couldn’t. It was all too much, too late. That reminds me. I’m meant to be doing a lottery. A fairy said I have to do it.

Is this all material for songwriting?

I don’t write songs!

Where do they come from when you do?

I don’t know, man!

Is there a time that’s good for songwriting? Before you go to bed, for example?

Maybe if I went to bed! [laughs] I generally stay awake for about a week. I get catnaps, and then when I’m really exhausted I crash out for a good long while and carry on, you know what I mean?

Do you think it’s still in you to create new material? Do you still want to write?

[Looking depressed] You should ask Paul a few more things.

I’m just interested in what inspires your greatest songs. Fairytale Of New York for example, is already a standard.

It will be with us forever. I’m wasting a lot of breath here. You know what I mean? I’ve done so much bellyaching over the years about this, right? I don’t really have anything to say, more than anybody else. What I’m interested in doing is having a great time, and the audience having a great time, and living as long as I possibly can, and I’m as much in the dark about what happens after that as everybody else. Except I have a faith, which is, which is, which is, you know… it isn’t anything to do with any particular… like people who… I mean, what’s it all about? Why don’t you tell me? What do you believe? What do you think happens?

You mean the meaning of life?

Yeah! I do believe in freedom for living things, and in free speech, but that’s got absolutely bugger all to do with you being English and me being Irish. These days we get on fine. We always did. Take the piss out of each other, whatever. It’s the same as the animals and the trees. I’m into hugging trees and stuff. There’s nothing stupid about hugging trees, especially if they surround you like they do out here.

Do you believe in the spirits of the land alongside the Catholic faith?

There’s a fairy fort near here. There are a couple of fairies down there at the moment. Actually, you’ve just given me an idea for a song. We don’t know what it is really, but it’s to do with Irish… actually it’s all over the place, but we’re custodians of this country, yeah? And I believe in what the older people believe around here. Call me a hippy, call me a whatever, you know… do you want to see The Fairy Fort?

I would like to, actually.

[Getting excited] You want to see The Fairy Fort? Yeah? Yeah? Yeah?

MacGowan leads the way out of the gnarled wooden door of the cottage — and promptly falls into a ditch in the long grass outside. “Help me,” pleads a voice in the darkness, as a sweaty arm can just be seen sticking out of the ditch. MOJO utilises all of its strength to pull MacGowan upwards, then holds his hand as he struggles to take the ten-minute walk down a narrow road towards a wooden fence looking out into a field and, beyond that, a copse with a faint glow around it. The copse is The Fairy Fort. It is six am.

“The fairy fort is full of sidhe, which is a Gaelic word for ghost or spirit,” whispers MacGowan, as he leans on the fence. “Only two people have ever gone in there. The first one came out and had to be taken straight to the lunatic asylum. Another came out with totally white hair.” MOJO asks if he ever spoke about what he saw.

-

READ MORE: Shane MacGowan's 20 Greatest Songs

"When he had calmed down a hell of a lot, yeah,” replied MacGowan. “He said there were voices all around him. But he kept his cool as much as possible. The Fairy Fort definitely sends a message to you: leave us alone and we’ll leave you alone. Wise women and wise men around here know that when people get really ill it’s usually a result of trying to collect firewood from there. It’s got to be left alone. I’m not going past this gate, simply out of respect for… well… the people who live here, I suppose. They don’t want to be bothered in the middle of the night by an idiot like me and another guy who is a bit calmer.”

It’s now six in the morning and freezing cold. MOJO takes MacGowan’s hand as we stumble back to the house, intermittently attempting to prevent him from wandering into his neighbour’s farmyard. On the way, MacGowan explains the secret of his lustrous head of hair.

“I’m going to have hair until I die. I don’t wash it — only in Tipperary water. It keeps growing. I can’t stop it,” he says. “But you know they sell all those lotions to cure you of baldness, yeah? They don’t work. There is only one way to cure baldness. You pour Guinness over your head, collect it in a bucket, and drink it in the morning. That’s called hair of the dog. It’s proven to work.”

We arrive back at the house, where Tom Creagh has finally collapsed. Paul McGuinness has ordered a taxi back to Nenagh, from where we will take the morning bus to Dublin. MacGowan offers to pay for a taxi back to Dublin, even though it would cost in the region of 500 Euros. We explain that we’ll be fine on the bus.

“All I’m saying is that it’s not a problem,” says MacGowan. “I can get you back, one way or another. You don’t have to worry about ordering taxis.”

We leave at 7am, as MacGowan pulls Euros out of his pocket to pay the taxi driver, some of which catch a gust of wind and fly up in the air in the direction of The Fairy Fort. We can only hope the unintended gift from MacGowan to the sidhe might bestow on him the powers to engage his muse once more.

This article originally appeared in MOJO 195.