In 2012 The Kinks’ well-respected man of British song Ray Davies spoke to MOJO about battles with his brother, booze, bad luck and the art of songwriting. “Writing is like running a marathon,” Davies told Pat Gilbert. “The important part is finishing.”

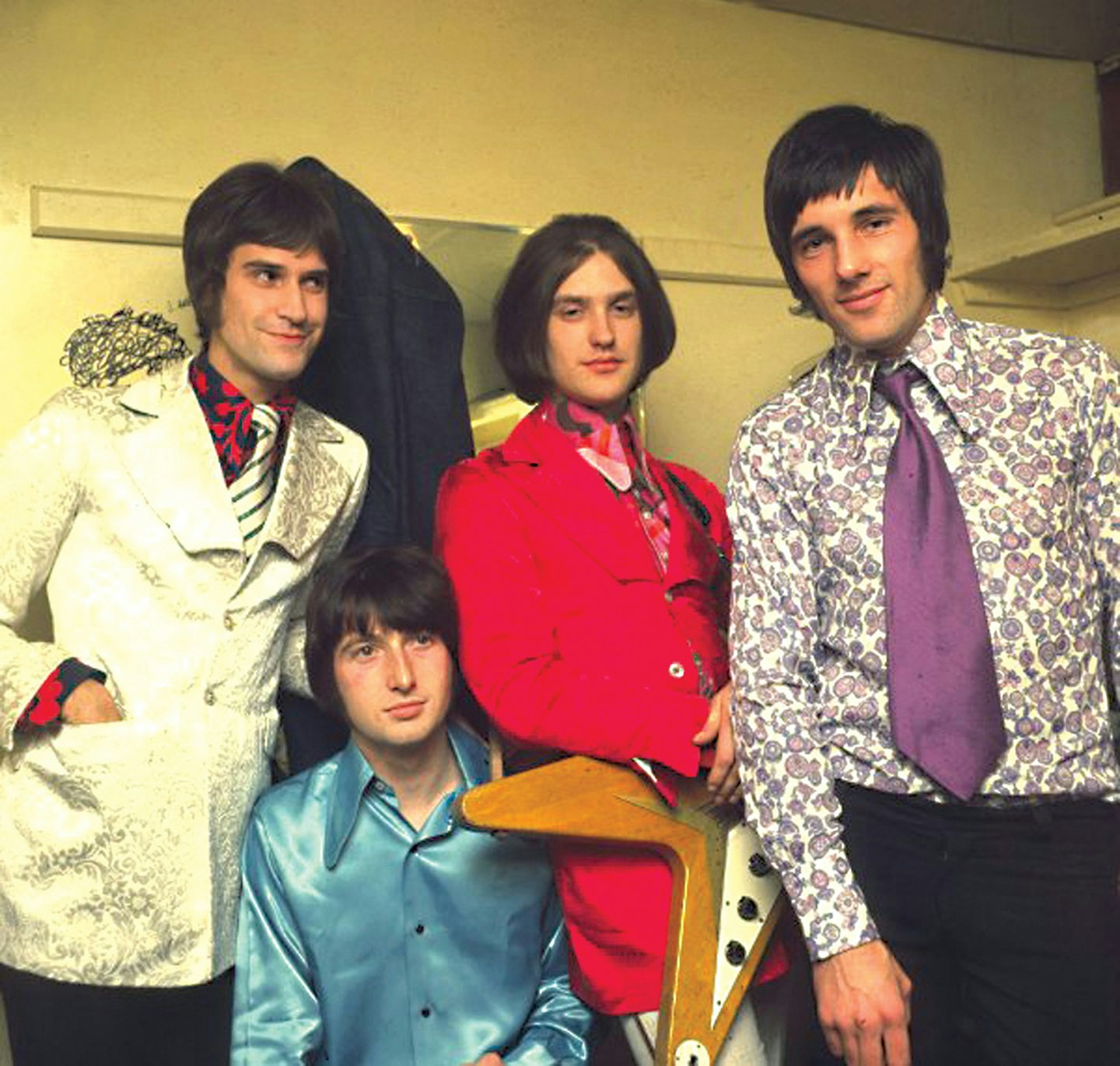

Picture: Ian Broudie

In the stalls of a dimly lit upstairs theatre at The Gatehouse in leafy Hampstead Village. Once a music hall, it transpires that almost everything here that looks Victorian actually dates from a more modern makeover. A gnawing feeling of not-quite-rightness is emboldened when, just 15 minutes into our interview, Ray Davies – chief Kink, peerless musical chronicler of post-war, working-class England, ’60s survivor, arch ironist – becomes noticeably distracted. Then, after saying he needs to “sort something out that’s happening later”, he gets up and leaves.

It had all been going so well. Twenty minutes earlier, Davies had arrived in a genial and upbeat mood. Tall and slim, with keen, watchful eyes, his subtly rusty movements and sedate, posh-Cockney speech nevertheless underscore the fact that the gap-toothed dandy of those colourful ’60s EP sleeves will turn 68 in the week of our meeting. As we shake hands, it strikes MOJO that it’s the very same hand that first picked out the chords to Waterloo Sunset, Sunny Afternoon, Dead End Street, Autumn Almanac, plus once forgotten, now revered late-’60s concept albums The Village Green Preservation Society and Arthur (Or The Decline And Fall Of The British Empire), through the band’s difficult “theatrical” works of the ’70s, including Preservation Acts 1 & 2 and Soap Opera, to late-’70s power-rockers Sleepwalker and Low Budget and a low-key millennial solo career.

According to Ray’s younger brother and fellow Kink Dave Davies, it’s also a hand whose unusual softness was considered by their working-class father to be indicative of an over-sensitive soul. It was a prophecy borne out in Ray’s subsequent life: special schooling; a nervous breakdown in 1966; constant wars with his brother; an infamous overdose during and after a 1973 White City show (following his split with first wife Rasa); retreats from the music business; occasional submersions in booze; even being shot during a mugging in New Orleans in 2004. Much of this, it seems, essential nourishment for an extraordinary songwriting journey.

MOJO is fully conversant with Davies’ semi-fictitious autobiography, X-Ray, in which a young investigator from “The Corporation” interviews Ray, who, in the fiction, is 70 years old. Their first meeting finds Davies testing the ingenue with a game of “emotional chess”. And in the first quarter of our interview, Davies will, unsettlingly, ask me to repeat two lengthy questions, and then claim not to understand a third at all.

But returned from his walk-out, he warms into a wry, humorous interviewee even giving MOJO advice on songwriting. “If after two weeks you still can’t write your middle-eight,” he says, “the best course of action is to see a psychiatrist. That will sort you out.”

During your childhood in a working-class terraced house in Muswell Hill, when did it strike you, as you would sing in a Kinks song, “I’m not like everybody else”?

I always felt that way. But you also have to say to yourself that you’re not going to be like other people. My daughter, who’s 13, said to me, “I’m not going to be like that. When I’m 18, I’m free.” So maybe a lot of young people feel like that, but you have to search for the thing that will put you on a different journey. Which for me was music, which I was performing in the local pub from my early teens.

You’ve said that you deliberately failed the 11-plus exam by leaving the paper blank.

A powerful statement for a 10-year-old?

Well, it could have been destructive if I’d taken it. The backstory is that, because I was seen as a loner and had health issues, I’d missed a lot of conventional schooling and had to go to a special needs place [in Notting Hill] when I was about 10. It’s not that I wouldn’t have passed the 11-plus, but maybe if I had then I would have been like everybody else. I had heard that the local secondary school was really good for people like me and it was a new era when the divisions between the different kinds of schools was diminishing and being de-stigmatised. I think I had something else on my mind that day and thought, Why bother, it’s ridiculous.

Dave Davies, your little brother, once said that people assume it’s the older sibling’s responsibility to look after the younger one, but it often turns out to be the other way around. Is that true in your case?

I always felt Dave was more mature than I was, in a strange way, more worldly, more adventurous. When I was at art college [in 1962], I did my art. I went to the clubs, but I was not hanging out or involved with all the excess Dave was, getting out of his brain at Jimmy Deuchar concerts. Jimmy was a jazz trumpeter, completely off his head. People used to go to his shows not just to see his excellent playing but to score their drugs. Dave hung out at more edgy clubs, while I stayed in a more R&B circuit. He was more intelligent, his attitude was just “do it”. My attitude was: give me time to think about it first. Dave was always the catalyst for things.

When did the ’60s start for you?

Maybe art college. Working-class people had access to areas they hadn’t before, which was good. It wasn’t a decade, it was just a magical few years. 1964 to… it was over by the time they made Blow-Up [1966]. It’s easier to determine with hindsight what an era meant. It was a golden age of creativity. When the classes mingled, it was full of possibilities.

In 1966, before you wrote Face To Face, the first all-originals Kinks LP, you suffered “nervous exhaustion”… Do songwriters have to go somewhere dark to create something extraordinary?

If writer friends are going through a bad patch emotionally, I always think, They’re on to something! (laughs). When you get a really big idea, sometimes those ideas are bigger than your abilities to express them. Sometimes I’m searching for a way to say something, but I only have songs to express it. With Sunny Afternoon, I knew something was going to happen. Then England won the World Cup and I thought, That was quite important. I wrote the song in the middle of quite a bad illness. People call it “nervous exhaustion”, but that is just an expression. It was a number of things. I had an injured back as a kid, which is why I sit a bit weird. That was giving me terrible pain. We were touring a lot, and the people who had problems on the road in those days were drug addicts, which I wasn’t. I was a young parent with a family and all the things attendant with that. It was the first time I began to think that the band wasn’t enough for me. Hence a lost few weeks… Yes, it bore fruit. But sometimes you have to ask yourself, Was it worth it?

It’s clear that the other Kinks – originally your brother, bassist Pete Quaife, drummer Mick Avory – were important to you. You never regarded yourself as a solo artist writing songs for ‘backing musicians’.

I think they felt sidelined sometimes when I did other projects, or wrote a song like I Bought A Hat Like Princess Marina that had nothing to do with jazz or R&B, which is what Mick wanted to play. But he followed along with it. That was true to the spirit of The Kinks. I think the overriding position was that, regardless of what I was writing, I always heard the band performing it. I always cast those players.

The story goes that you were forced into exploring Englishness in your songs because, after a ruckus with the American unions, you were banned from playing in the States between 1965 and 1969. Has that been taken too literally?

Yes, because I was writing English songs right from the start. My heroes were Chet Atkins, Big Bill Broonzy… So I wanted to make my own blues and I think I was heading in that direction anyway. But it was the American touring that pulled the plug on everything. Writing songs with English themes became a way of cocooning myself away. Protecting myself. We were due to play Monterey, Woodstock, one of those big festivals, where everyone was emulating our style. The only person who gave us credit for what we did was Jimi Hendrix. He Mitch [Mitchell] and Noel [Redding] all said the greatest band they ever saw was The Kinks. A lot of our peers said we were finished, but we were still making records. You had to tour the States to get on American TV shows. If you didn’t get a foot on that continent you couldn’t get promoted.

Did it irk you that Pete Townshend got there first with the rock opera? Tommy came out after the televisation of Arthur had fallen through…

The bits I’ve heard of Tommy and the Ken Russell film of it seem to be more of an impressionistic version of a rock opera. It’s not a rock opera, it’s its own art form, which is good. Arthur was designed as a TV musical. If it had been done it would have pushed the boundaries of TV and art. For a long time, everyone knows who did it first, but then everyone knows who got there first… (smiles).

Were you rivals with Townshend?

No. We were different. We weren’t in the same league (laughs). The High Numbers opened for The Kinks, on several occasions. I always knew they’d be outstanding someday. When I say “a different league” to The Who, I mean we were playing a totally different game. The Kinks were always in their own little world, while The Who, Led Zeppelin, Jimi all went off on that very American journey, very corporate. Pete and I are friends but we don’t push it. We respect each other, and part of that is respecting each other’s privacy.

Did that trouble you, that all the ’60s Brit rock bands made it in the US and you, at that time, didn’t?

It was frustrating not being able to take your work to the world’s biggest and most important market. But when the ban was lifted we began playing, at first in little rooms supporting people we shouldn’t have done, just to get gigs. It’s part of the journey, you can’t wish it was different because that was the way it was. The Kinks weren’t afraid to fail, and without any disrespect to The Who and Led Zeppelin, everything about those bands was built to succeed. I remember in the late ’60s one American band [The Turtles] phoned me up after they had a Number 1 hit and said, “I want you to fly to America to produce an album for us.” I said, Why do you want me? I can’t tour in America and my records don’t get played in America. All I can bring you is failure. They said, “But there’s poetry in that failure.” So The Kinks were allowed to be more poetic because there were no expectations for record companies demanding a certain type of record. We were allowed to be experimental.

"It was like being bullied at school..." Ray Davies on being put down by John Lennon

Many documentaries on The Kinks fast-forward from Lola Vs. Powerman to Sleepwalker, missing out the band’s “theatrical” period in the mid-’70s.

Yes, in this country, certainly. But during that Preservation era [two albums, Act 1 and Act 2, appeared in 1973 and ’74] the band was really tight. I know The Kinks had a reputation of being unpredictable on-stage, but oddly enough, on the shows that had themes to them – Soap Opera, Schoolboys In Disgrace, Percy – the band was much tighter as they were playing to cues. There’s less space for improvisation, so it’s very tight. It showed a good evolution of a band that was born to make R&B evolving into making its own style of music.

As a famously guarded individual, was it difficult when the overdose of Valium you took during the White City show in July 1973 became big news?

(Pause) I come from a super-simplistic world where I thought people liked songs like [1968 single] Wonderboy because they were nice tunes. I had no idea that they saw inside it. They saw the depth; I thought that just belonged to me. But having your private life made public is difficult. I’m still protective of my privacy, particularly in this age of celebrity. I wouldn’t know how to play the celebrity game even if they paid me. I wouldn’t be very good on it.

Do you remember playing the White City gig?

Not very well. I know I wanted to stop playing music then. My brother persuaded me to carry on. He was totally manipulating me. Perhaps with good intentions.

You hadn’t done the drug thing in the ’60s…

(Interrupts) I did. I did all that at art college. I gave it all up when I became a rock musician. I’d already done it.

Alcohol didn’t ever fully get the better of you. Or did it?

(Pause) Yeah. Not many people know this, but I was living alone in 2000/2001. I was living in an isolated place and drinking heavily. I watched the same film over and over again for three weeks. It comforted me, because I knew every line. I’m not going to tell you what it is. It’s a foreign movie… But alcohol did get the better of me. I was having sleep problems. But drink doesn’t cure sleep.

Did you feel threatened by punk’s arrival?

It was one of the happiest times of my career. Some of the funniest gigs I ever went to were down at the King’s Head. If you look at the backdrop of austerity and strikes… people were finding art in a naïve way of playing. All that spitting and self-harm were indicative of a generation that quite literally had no future. But the people who articulated that – with the Sex Pistols it was Malcolm McLaren – they were a class above that. It was like the kitchen-sink era, people like Tony Richardson and Ken Loach were white middle-class people. Music was already being taken over by clever entrepreneurs who were above the people they were writing about. When you saw through that it was a fun, chaotic time.

Did you feed off its energy for the “rock” albums that you made for Arista?

It brought out the vaudeville in me. Low Budget [1979] was overtly in the London vernacular. It was a curious time because we were starting to make it in America, which was still Styx and big hair and perfect guitar phrases. It was a fine balancing act between something that was affected by punk and being British and doing something suitable for US stadium shows. When we were touring Low Budget some people came up to us in Dallas and said “You’ve written something that’s affected us all.” So something that was a reaction to an English situation became one of my biggest albums, and still to this day much loved in America.

In the late ’70s, were you flattered when Paul Weller overtly took on aspects of your songwriting and sound in The Jam?

I was very honoured to give him a MOJO Award [in 2005] because he started in that era but evolved his own style of music over time and many of his contemporaries didn’t. They released a couple of angry singles and disappeared. I still call people like him “kid”. I don’t mean to put them down.

Did you feel a bit old when on Top Of The Pops with Come Dancing in 1983?

I didn’t have to wait that long. I was 26 years old and performing Autumn Almanac on TV and I said, “I’m too old for all this.” The feeling of coming from an older generation happened 15 years before that. With Come Dancing, it was justified. We were vindicated, because we showed we were still making good records.

How important was image to you?

I was never a pretty boy, I was never a teen idol. It never affected me. People who like me are interested in what I’m writing, not what I look like. ’Cos I look like shit at the moment!

The Kinks carried on ’til the mid ’90s. You called it a day after Phobia when your relationship with Dave broke down, but it had always been a fractious one.

Yes, but we are brothers, which is a complicated relationship. He was more receptive to the rest of humanity than I was, I was an insider and he was “of the world”. I haven’t seen him for a while, but it’s always been like that. Should I be more like him? When I try to be more receptive to the outside world, that’s when I get in trouble. I’m gullible. I take people’s word for things. Where Dave is more grown up.

In 1993, when you weren’t yet 50, you wrote X-Ray, your own “unauthorised biography”. A future version of you is interviewed. Did that help you to discuss personal things?

People think X-Ray is fiction, but the bits that appear to be fiction are actually the most truthful parts of the book. I read other rock stars’ books and it was just names, dates and places. With some people you want to understand the psychology of what they did. I wanted it to become surrealist. My life has been surreal. That idea of the 19-year-old confronting the 70-year-old man put a perspective on what I did. And it certainly helped me.

Do you see your “classics” as a body of work you can’t top? You’ve revisited them twice this decade, with the Crouch End Festival Chorus, then See My Friends’ collaborations.

The See My Friends project was a very frustrating time. It’s great having Bruce Springsteen wanting to sing one of your songs but it was much better when he said, “What’s that you’re playing?”, and it was a new song. So it’s good that doing that album brought out some new stuff in me.

To wit, 2007’s Working Man’s Café, a good album, redolent of the style of your ’60s Kinks work. But it made no impact.

The reason is simple: the record company got into trouble, then it was given away with The Sunday Times. That killed off any ability to promote it properly. Timewise, emotionally, it was a very big gift, because you’re giving away your work for free. It’s over, it’s transient; that’s why I admire real art, paintings. You can’t hang a record on the wall. It was a bittersweet time.

You conduct songwriting seminars. Can you really teach people how to write songs?

No, you can’t teach people, but I say to them I can guide and help them. It’s about sharing. What is your take on the importance of songwriting? Why do we need it? It’s a form of self-help. It’s like counselling. The song Wonderboy [1968 single] – I was expecting my second daughter, Victoria, and in that song is all the layers, the cathartic feelings, the problems, the images, my thoughts on my position in the world, why I should be a parent… I called it Wonderboy because I didn’t know it would be a girl. It wasn’t a great hit but that doesn’t matter. That work is out there. Writing songs is like running a marathon; the important part is finishing.

There are echoes of Wonderboy in Oasis’s song She’s Electric. Do people revisiting your melodies bother you? It happens a lot.

Well, I was rehearsing with my new band yesterday and we ended up playing with some old Chuck Berry licks. It’s inevitable. The funniest thing was when my publisher came to me on tour and said The Doors had used the riff for All Day And All Of The Night for Hello, I Love You. I said, Rather than sue them, can’t we just get them to own up? My publisher said, “They have, that’s why we should sue them!” (Laughs) Jim Morrison admitted it, which to me was the most important thing. The most important thing, actually, is to take [the idea] somewhere else.

When you were shot in New Orleans in 2004, chasing after a mugger who had stolen your girlfriend’s purse, what goes through your mind? It seemed a brave thing to do.

Foolish might be a better word. (Pause) I don’t like to talk about it. I’m quite determined. I’m quite mild-mannered, but when I get cross I don’t care what I do. Does it happen often? I try not to let it happen. But things happen.

You could have a lucrative sideline writing pop hits for people. Why don’t you?

I never get asked. I rarely get commissioned to write anything, with the possible exception of the choral piece. Maybe I’m too exacting – as opposed to difficult to work with (smiles). If you don’t have a deadline you tend to get into murky waters and drift. You need a deadline.

What do you think will be your legacy?

I think I’ll be like my character in my book, X-Ray. I’ll leave a box of tapes in a treasure chest you can go through and try to work out the real me.

This article originally featured in MOJO 226