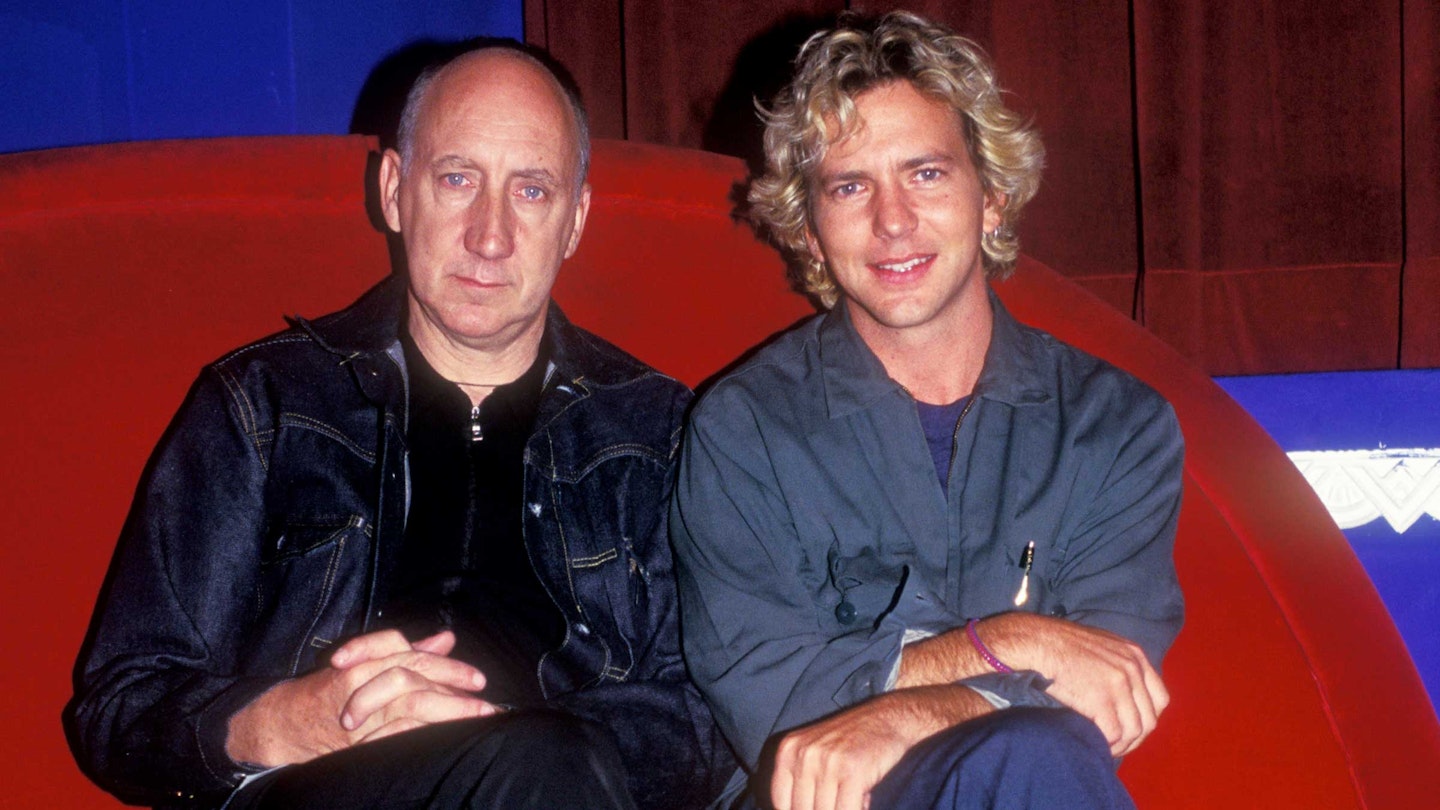

IN THE LATEST ISSUE OF MOJO magazine (MOJO 340 – on UK newsstands now) the subject of the in-depth MOJO Interview is Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder, looking back on his career so far and delivering the latest on his upcoming solo album, Earthling. Helping contextualise Vedder and his work is friend and admirer Pete Townshend; the Who man supplies a pithy quote to the magazine feature, but it’s only a few words out of the many that tumbled out of him when he spoke to MOJO shortly before Christmas 2021.

In the director’s cut posted here, Townshend is at his eloquent best, going deep into the connections between himself and Vedder and the advice he’s given the Pearl Jam singer over the years.

But also, in the wake of the Instagram videos that Townshend posted on November 14, 2021, where he revealed he’d spent three late nights working on a demo of an unreleased song dating from the Lifehouse/Who’s Next period, it would have been remiss of MOJO not to enquire further, and Townshend reveals his latest thinking around reissues, the long-threatened Lifehouse graphic novel and more.

Pete Townshend interviews rarely end up where you expect, and this was no exception, as the conversation whirled around Quadrophenia, the Cincinnati concert tragedy, and journeyed still further out there, embracing neotericism, telematics, computer love and further intellectual spitballing with this ever-enquiring mind.

“Journalism, for me, has always been a part of the feedback process,” Townshend told MOJO. “I think a lot of ideas and positions that I’ve been able to kind of work with... it’s been like therapy, and sometimes just to be able to do an interview and read it back and think, ‘Oh, fuck! Oh, fuck, I told the truth!’ And be shocked by what it is that has been revealed.”

When did you and Eddie Vedder first meet?

I met him in 1993, I remember it very well. I was at the Berkeley Community Centre, doing my solo show Psychoderelict. And it was a good night, that night. There were some good nights and some bad nights on that tour. But that was a good night. And Eddie was in the audience. I recognised him standing up in his sort of German military jacket. And he stood up through the show, while a lot of people were sitting down, so he was very visible. I remember him looking a bit lost.

Anyway, after the gig, I had about 30 visitors, because San Francisco is a place where I spent a lot of time over the years. And my manager Bill Curbishley said, “Before you see your guests, I want you to meet this young guy, Eddie Vedder, who’s the singer in Pearl Jam.” And I said, “OK.”

So he walked in and sat down and we started to make small talk. And he said, “I fucking hate this. I just hate it. I don’t want to be famous. I don’t want to be in a band. I’m feeling like I just want to run away. I grew up on the beach in La Jolla surfing. And that’s really what I want to do for the rest of my life.” And he said, “I’ve heard that you’ve been through similar stuff” – because, 10 years before, I had left The Who.

I remember saying to him, “I’m afraid it’s too late.” And he said, “What do you mean?” And I said, “This isn’t like politics, you know, you don’t put yourself up for election, get your seat, fuck up the country and then retire. What you actually do is get railroaded. You just get grabbed and put on the stage, and told to keep doing what you’re doing until you’re allowed to stop. And you have absolutely no choice. You’ve been elected without standing. And you just might as well enjoy it, because it’s not going to go away.”

Anyway. We both sometimes speak about that conversation. And I think it did help him because I think it’s true. I think that’s what happens.

But with Eddie, I think the thing we have never talked about is his loyalty and his commitment to his band. Because he also wants to express himself as a solo artist and as a collaborator. And he’s a writer, he’s one of the key writers for Pearl Jam. So it must be overwhelming, but he stuck to it. He seems vigorous to this day. You know, he’s well past the kind of 34-year-old fuckwit that I became, when I was done dangling big record deals with The Who and playing stadiums and trying to do solo albums all at the same time. He seems to be managing really well.

So that’s when we met. And since then, we’ve been very good friends, but it goes further than that. He’s also very good friends with my brothers. My two brothers are much younger than me. Simon is 14 years younger and my brother Paul is 12 years younger. And they still live in the same street that I grew up in. And often I’ll hear from, you know, somebody in Ealing Common: “Oh, we saw Eddie Vedder and your brother Paul in the pub the other day.” I’m like, “I didn’t even know he was here.” “Oh, he was just passing through but he bought a few rounds.” In other words, people in Paul’s local pub in Ealing know Eddie Vedder probably as well as anybody.

Eddie loves The Who, but he also gets The Who. You can hear it in his Who cover versions or when he joins you on-stage. For instance, he does a version of Blue, Red And Grey [from The Who By Numbers] on the ukulele that really helped me rediscover the song. It must be gratifying to have someone really understand what it is you’ve been trying to do...

You’re absolutely right, but there’s another angle on that. When you have fans who are working musicians, and if there’s at least a 10 to 15 year gap, the relationship becomes respectful, and even exalting. I’ve been through it myself on occasions, when I’ve finally got to meet people like Little Richard or The Everly Brothers or Brian Wilson. But the punk movement in the UK changed things. It created a particularly British mechanism (chuckles), which is: ‘We love you, but you’re a complete and utter c**t! And we think everything that you did up until the point that we were born was really really great. But since we’ve been born, you’ve just turned into a big pile of rubbish.’ And this is you know, Britpop, it’s The Jam and it’s Oasis...

The difference with Pearl Jam and I think also with Nirvana – who were also Who fans – is that they were able to kind of roll with it, I suppose, and live with it. You see it in a huge way in country & western music, in particular in America, and maybe in folk music, where the older artists are not just respected and lauded but also allowed to continue, not to just roll over and die. A lot of my midlife shit was about the idea that I too felt that I should roll over and die. And I think that is very much a British thing. That you mustn’t outstay your welcome. And you must also embrace new ideas. They call it neotericism. It’s when you value the new more than the old, whether or not the new or the old is better. With Eddie, there’s no question. He doesn’t feel he has to be embarrassed for being a Who fan.

Back in 2019, when he supported The Who at Wembley, Eddie came on-stage with you and sang The Punk And The Godfather [from Quadrophenia]. His connection with that song is interesting, because it goes back to his dilemma in 1993, and yours at the end of the ’60s. You’d both been associated with these youth movements – him with grunge, you with Mod. It gave you this extra wattage, but it brought an extra burden.

I think that’s interesting and you’re right. Eddie’s often stood in on Quadrophenia concerts, and when my wife [composer/arranger Rachel Fuller] and I did the Classic Quad tour [Pete Townshend’s Classic Quadrophenia, 2015], he did a couple of walk-ons there. But you know, when I wrote the Quadrophenia album, I was already looking back at an era. If there’s anything truly strange and fascinating and weird about the Mod movement, it was that it was the old stealing from the young.

I did a thing for Sadie Frost talking about Mary Quant the other day, and it was very difficult for me not to tell the story about the fact that my first girlfriend at Ealing [Art College] was making mini dresses long before Mary Quant even thought of them. There was sort of a vampirism at work. And it was weird, because at the same time you had this rediscovery of old ideas, old music, old legends, you know, whether it was Woody Guthrie, whether it was Leadbelly, whether it was Miles Davis, whether it was Coltrane or Charlie Parker or Louis Armstrong, or Bill Haley or, you know, any of the country stars that preceded them all. And we processed them all quite quickly and off we ran with them.

I’ve gone off sideways a bit, but I do think there’s something there – a sort of a mirroring between the grunge bands of America and the early kind of pop-rock bands like The Who and The Kinks in Britain who were just sort of writing from the hip.

Youth movements always have this experience of co-option, where the marketeers move in. That was definitely something that plagued the grunge bands, something that they kicked against almost immediately.

Well in ’93, I was mainly hanging out in New York, supporting the theatrical version of Tommy and I remember there being this incredible concern, among the journalists I came across, for what was happening with the grunge bands. A concern for their mental health. There was no sense of Schadenfreude. And it felt to me as though there was an echo of what happened in the ’67 to ’69 period in America, where there was a sense that the music business was a reflection of what was happening on the streets and in society. And the journalism was entirely supportive.

In a sense, what Eddie went through at the beginning was really just a crisis of freedom. You know, that sense that, as a young man... I’m not quite sure about the family background, you may know more than I do. But I met one of his brothers quite a few times. He was really, really wild, and I don’t know whether he ever came back down onto the planet. And when they were kids they literally lived on the beach.

A more obvious thing Pearl Jam and The Who share are the concert tragedies. They had Roskilde [June 30, 2000, where nine people died during Pearl Jam’s set] and you had Cincinnati [December 3, 1979, when 11 people died in a crush at Riverfront Coliseum]. Both were devastating for the fans and their families. But I also think that people struggle to understand the impact on the groups...

For us, it came close on the heels of the death of Keith Moon. So it was a double blow. I was definitely still really pretty fucked up from that. When Roskilde happened, I just sent Eddie a two-word message: “Don’t leave.” And they did stay. And I think it was very important that they did.

Your advice was to stay in Roskilde? And talk to people and deal with it?

Yeah. Because what we did [after Cincinnati] is we left, we left the next day, we went to Buffalo. And I remember going on the stage, and Roger saying – and I should really make it clear I was perfectly behind what Roger said at the time – “Let’s play this gig for rock’n’roll and the kids of Cincinnati!” It was just entirely inappropriate. I mean, just wrong. You know, we shouldn’t have gone on, we shouldn’t have performed.

But yes, it’s something that we have in common, and I think it was... How was it disturbing? It’s disturbing because one ends up carrying a tainted flag. I was such a flag-waver for the rock’n’roll ethos; I believed something magical happened when great music took place in public. And I think it’s something that still happens. But I think I exalted it perhaps too much. And I think, therefore, when the moment came that everything went wrong, you look and you think, “Is this our fault?” And although you don’t, you know, want to live with that for the rest of your life, the answer has to be yes. There can’t be any other answer. Whether or not that responsibility extends to huge insurance suits is another story.

But the emotional impact is carried differently by every individual. I think, for me, I sort of buried it for a long time. I’m not very good with grief, and I’m not very good with drama. So what actually happens is that I tend to internalise it and it pops up later. In fact, Eddie and I have never talked about it since. A few people have said to me, “Are you gonna reach out to Travis Scott [after eight fans died at the rapper’s concert in Houston in November 2021].” And I thought, “You know, what could I say? What could I say that would help?”

So anyway, it does unite [Eddie and me] I suppose. It does. In fact, if next year we do get back to America, and I think we will, we’re doing a really big event for a Cincinnati foundation. It’s taken a long time for us to get to a place where we can talk about it in public.

One of Eddie’s favourite Who songs is Naked Eye. And I suppose that makes me think about Lifehouse, and the developments you hinted at on the internet the other day. Is there anything more you’d like to say about your plans for Lifehouse this year?

No, I actually don’t have any. I mean, 2021 would have been the 50th anniversary of the Who’s Next album and a good opportunity to do a box set and to have conversations about it. But we missed it for obvious reasons. And so in 2022, there is a box set and the box set is to some extent being perfumed by the fact that I’ve been working with a guy called Jeff Krelitz on a Lifehouse graphic novel, and we’re hoping that that will come out around the same time. There’s talk of a documentary, all of this stuff. It makes me want to run away (laughs).

What’s interesting about the Instagram post is I was obviously having a lot of fun. I watched it again the other day, and somebody said to me that I looked like I hadn’t slept for six weeks, let alone three days. But what happened was this – the record company had found a track they said was from the Lifehouse sessions. This track, called Ambition, had Keith Moon, John Entwistle and me playing on it. And then I found a demo that I had done at home with a vocal. So they were like, “Well, let’s just get Roger to do a vocal on the version that the other guys in the band did, and we can add it to the record and it will be brand new.” So I spent a week reconstituting or finishing off the demo, sent it to the record company, and they said, “Ahhhh, no... Maybe you could put it on a solo album?” So I said, “Well, you know, there’s reason it’s never been released before. It’s because it’s crap!”

But Naked Eye itself has got nothing to do with Lifehouse at all. It’s been associated with it because it was played, I think, at the Young Vic [a run of London shows in early 1971; a version from April 26 was a bonus track on the 2003 deluxe edition of Who’s Next]. But the thing about Lifehouse, which I think goes way, way, way beyond ideas that men like Bowie... and possibly well into the kind of grandiose, sweeping, techno-thinking of Brian Eno or someone, is this idea of there being a possibility of a technological breakthrough which is part of a music album. And that’s what I still yearn to see happen, you know, whether I pull it off or whether somebody else pulls it off.

I often think back to when I was a kid, I must have been between maybe 12 and 13. And my dad, despite the fact that he was a musician, didn’t have any record playing equipment. But he had a friend that did, and I remember going over and listening to the two records he had: Songs For Swingin’ Lovers by Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald Sings The Cole Porter Song Book. And they were ‘pseudo stereo’; they were recorded with one mike in front of a band and an orchestra, which is how they used to record in the ’50s, but with a nod of the head towards stereo. And it felt to me as though technology and art and popular music had made this huge step forward together and I suppose that’s what I’ve always dreamed would happen again: that one day we would get something through the letterbox and inside would be this magical thing.

And your dream would be that Lifehouse would come out, and embrace or be embraced by this radical new technology?

No, no, I don’t think it’s possible now. No, I think it was just the way I was thinking at the time. A lot of that was post-art school thinking. I’ve actually been reunited with Roy Ascott, who was my lecturer at Ealing, who was really big on cybernetics and computer technology and, you know, the singularity and all of that stuff, way back in 1961. And he’s now a professor at Shanghai University, teaching something he calls telematics. And telematics is just electronic communication technology, but with the AI principle written into it. And one idea is that if machine learning grows quickly enough and elegantly enough, it will mean that love is introduced into computer machinery in such a way that much of what the human race does to destroy itself will be happily impeded (laughs). And in a sense, that was running behind Lifehouse, this absurdly huge idea which I wasn’t even able to get properly on paper. And, you know, for fuck’s sake, I was in a fucking rock band that used to throw televisions out of the window! (laughs)”

FIND OUT MORE ABOUT MOJO 340, AND/OR PURCHASE A COPY

Photo: Getty Images