Starring Timothée Chalamet as Bob Dylan, director James Mangold’s new biopic A Complete Unknown is rightfully gaining plaudits for its portrayal of Dylan’s rise to fame and his schism with the folk scene that nurtured him. A few weeks prior to Dylan’s seismic appearance at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 depicted in Mangold’s film, Oscar-winning filmmaker D.A. Pennebaker followed the singer on his European tour, shooting footage that would emerge in 1967 as Don’t Look Back in. Now regarded as a milestone in filmmaking, Don't Look Back revolutionised the way music documentaries were made and showed Dylan in an entirely new - and not always complimentary - light. Before his death in 2019, Pennebaker spoke to MOJO’s Michael Simmons about the making of the film and its follow up, Eat The Document…

-

READ MORE: The Making of A Complete Unknown: “Bob liked what I was doing and saw that I didn’t have an agenda…”

“I didn’t know much about Dylan at the time,” says filmmaker D.A. Pennebaker as he recalls the birth of Dont Look Back and, later, the tale of its missing apostrophe. “But there was a story there – I could feel it in my bones.”

The master American documentarian has been revered for six decades of fly-on-the-wall cinema, from early editing work on the 1960 Direct Cinema documentary Primary, to rock landmarks like Monterey Pop and (with wife Chris Hegedus) more recent award-winning films such as The War Room and Kings Of Pastry. He is gratified that he’s still asked about his classic 1967 account of Bob Dylan’s ’65 English tour.

“It had a much greater effect than I imagined,” admits the loquacious 87-year-old Oscar-winner. “I’ve had many people say that it didn’t change their life so much as fix it, that maybe what they’d toyed with they now had a definite sense of.”

Music was inspirational for Pennebaker, and he credits a lifelong love of jazz for his improvisational documentary technique. “[Jazz] is how I learned to edit film ’cos I never went to film school. The way in which fantastic musicians could reduce a song to three minutes and do it in a marvellously musical way, that it had an arc to it – that’s the way I edit films. You learn the wonder of making up stuff as you go along.”

By the early ’60s, Pennebaker was one of the pioneers of the cinéma vérité movement that emphasised naturalism, lack of narration, and improvisation in the pursuit of a new form of cinematic realism. He also helped develop a new system for shooting, with a battery-operated 16mm camera on a shoulder-mounted cradle, camera and tape recorder synched without cables via a speed-regulating crystal oscillator, allowing the camera operator and sound recordist to move about independently.

In early 1965, Pennebaker received an invitation from Bob Dylan’s manager. “Albert Grossman asked me if I wanted to go with Bob on a tour they were gonna do through England. [They’d let me] make the film I wanted to make and it was a hand-shake deal with Albert. At that point the camera pretty much worked as it should. I had a couple of people working with me. Jones Alk – who was doing sound – was married to [second] cameraman Howard Alk. But I didn’t really need anybody else – you could do it by yourself. That was the most important aspect of this kind of filmmaking; one person could do it, like one person could paint a picture or write a book. It made [filmmaking] expand in all different kinds of ways. Nowadays you can see where it’s gone – everybody’s making a film of their butcher and their father and their mother.”

While he had no idea of what he might encounter as the director, Pennebaker had strong feelings about what to avoid. “I wanted it to be a film about a musician, but I made sure no song plays its full length. It was about a person confronted by having to deliver music. His audiences were there to hear what he said – what the songs were about.”

Pennebaker began filming at the end of April 1965. Dylan’s entourage consisted of Grossman, tour manager Bobby Neuwirth, and companion and Queen Bee folkie Joan Baez, with walk-on appearances from Allen Ginsberg, ex-Animal Alan Price, Marianne Faithfull, Derroll Adams, and Dylan’s alleged UK counterpart Donovan. “[The film] had people in it,” explains Pennebaker, matter-of-factly, “and wherever there’s people there’s likely to be drama. If you get admitted to the family, you get to be in the kitchen when the shit hits the wall.”

Shit and wall repeatedly connect in Dont Look Back, a result of Dylan’s confrontational disposition, the colourful co-stars and cameo characters, and the manic demands made on a popular young performer on the road. No small example of the inherent drama is that Dylan’s relationship with Joan Baez was drawing to an end. We see him pointedly ignoring her, while she gamely reminds him of great songs he’s written and discarded (Percy’s Song, Love Is Just A Four Letter Word), singing them off-stage and showing her dignity and obvious affection for him. Neuwirth, however, appears outright cruel, saying about Baez, in front of her, “She has one of those see-through blouses that you don’t even wanna” – a line lifted from a Lenny Bruce routine.

Pennebaker also captures the liquid revelry typical of a pressure-cooker tour, notably the ‘Who Threw The Glass In The Street?’ sequence in a crowded hotel suite where a drunk Bob demands that the other drunk who threw the glass identify himself. Fans may have heard rumours of their favourites acting up, but they’d never seen it on screen.

Some of the most compelling scenes star Albert Grossman – the master control-freak – conniving for cash with concert promoter Tito Burns or calling an irate hotelier a “fop” and “dumb asshole”.

One wonders if Grossman was comfortable being filmed, but Pennebaker believes as cameraman, he became invisible: “We found that when people were doing something they cared about, [we] just dropped out of [their] sight because they didn’t have time for somebody with a silly camera watching them.”

The film is also punctuated by a series of press conferences and interviews, in which Dylan gives absurdist or angry answers to what he believes are simplistic or limited questions. Most unsettling is his takedown of Horace Judson of Time magazine. Judson was no hack – he was also a historian of molecular biology – but when he asks Bob if he cares about what he sings, he comes across as a quintessential Mr. Jones, aware something’s happening, but clueless about its meaning.

“It didn’t occur to the papers that a particular kind of person should do the interview,” explains Pennebaker. “The guys came with no idea about Dylan at all – nor did it matter to them. What always bothered [Dylan] was throwing pearls to swine; that people who don’t understand how things work on the street – that they’d want a quick, easy answer. It bothered him that they expected him to do it. I saw him as a Kerouac kid. Kerouac got down on his hands and knees and saw things from the view that most people didn’t.”

Though truncated by Pennebaker’s intention not to show them in entirety, the concert scenes are sublime: even Dylan walking to the stage is exciting – the director’s new system allowed him to follow Bob through narrow backstage halls – a shot later brilliantly parodied in This Is Spinal Tap. The live footage also reveals Dylan at an historical point of transition. Singing his earlier finger-pointin’ songs like The Lonesome Death Of Hattie Carroll and The Times They Are A-Changin’, he sounds disengaged, bored, rushed – as if he’s eager to finish, be done with them.

His first so-called “electric” album Bringing It All Back Home had been released a month before and – while he’s still performing solo with an acoustic here – he’s already a rocker in look and attitude, most affectingly during a scene where he’s staring in a Newcastle guitar shop window. “They don’t have those guitars in the States, man,” he laments.

When he sings the newer songs – It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding), Gates Of Eden, Love Minus Zero/No Limit, It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue – Dylan becomes electric, and, of course, the film begins with the landmark Subterranean Homesick Blues sequence in which Bob holds and discards the lyrics written on boards while Ginsberg and Neuwirth kibitz off to the side. It was done in one take on the last day of the tour, although the idea was conceived while they were still in the States: “We brought all these shirt cardboards from America.” Donovan, Jones Alk and others wrote the words on the cards.

At the end of the tour, Pennebaker returned to New York and examined the footage. He decided to edit it all chronologically, the two exceptions being the Subterranean opener and the segment that follows a BBC African correspondent asking Dylan, “How did it all begin for you, Bob?” At that point Pennebaker cut to a snippet from two years earlier, where a work-shirted Bob performs Only A Pawn In Their Game for civil rights workers in Mississippi. It’s the only scene in the film not from the ’65 English tour and its powerful presence was pure serendipity.

“The guy that shot it was a friend [Ed Emshwiller],” explains Pennebaker. “He’d been down there doing a film on Civil Rights and they’d filmed Dylan. He said, ‘I can’t use it,’ so he gave me this roll of film. I was working on [Dont Look Back] and didn’t even look at it – I stuck it overhead on a rack. When I got to the moment where the guy asks, ‘How did it all begin?’ I thought, That’s an interesting question. So I pulled that film down and ran it. It just seemed perfect to me.”

Pennebaker also discovered something else – he had enough to release the film as a feature. “I didn’t set out to make that. It was only after I edited it and looked at it and realised what it was that I wanted to go into theatres with it. But it was hard because we weren’t connected to theatre distribution and distributors looked at it and said it’s too ratty-looking! [Finally] a guy came to us who said, ‘Somebody told me you had a film I should look at.’ Afterwards he said, ‘It’s just what I’m looking for – it looks like a porn film but it’s not’

“He had a string of porn theatres all over the West and he said, ‘I’m gonna give you this fantastic theatre in San Francisco.’ It ran there for a year and from then on it was a feature film. You didn’t have to say it was a documentary – you didn’t have to use that terrible word. That word absolutely assured you of relapse of any theatre’s interest.”

By 1965, Dylan was a beguiling movie star: mysterious, charismatic, a natural performer on- and off-stage, a complete original. “Even when Bob talked, he’d mix things around in a funny way. He was messing around with language and he didn’t understand what he was doing sometimes, but the lines that would come out would be amazing. He had the ability that a good poet has, of turning you on to meaning within words that you hadn’t bothered with before.”

By focusing on the human vagaries and bad behaviour of Dylan and his entourage, refusing to mimic the three-minute song formula of a musical variety show, Pennebaker devised a template that would be built on by countless later music films.

As to the film’s title, Pennebaker acknowledges the Dylan lines “She’s got everything she needs/She’s an artist/She don’t look back”, but maintains he got the title from Negro Leagues’ baseball great Satchel Paige, who famously said, “Don’t look back – they may be gaining on you.” Dont Look Back would be his first feature film and the first using the improved 16mm sync sound system. Pennebaker captured Dylan revolutionising music while he revolutionised film.

When asked why there’s no apostrophe in the first word of Dont Look Back, he says, “I got tired of everything looking like everything else. And I thought, Fuck it.”

In 1966, when Dylan went out on a world tour with The Hawks he came back to Pennebaker with an offer of another film. “Bob said, ‘I’m gonna direct it, but I want you to shoot it.’ I was just the cameraman. I was curious to see what he’d do, directing a film.”

The ABC television network had commissioned the film and what they saw is the stuff of legend, bootlegs, and, on occasion, YouTube. Shot in colour by Pennebaker and Howard Alk, with Jones Alk and Neuwirth recording the sound, the result was Eat The Document, an idiosyncratic mix of Dylan and The Hawks’ live UK rampage, cut up with Dadaist set pieces from Bob and the boys.

However, the ABC execs declined to air it and it’s not difficult to see why. In the first scene, Richard Manuel snorts something off a hotel dining-room table as Dylan laughs hysterically. Later, the two go for a stroll and Manuel tries to “trade my jacket, a can-opener and my cigarettes” for a young man’s girlfriend. Again there are backstage guest stars such as Johnny Cash, but both he and Bob are visibly trashed as they sing I Still Miss Someone.

The famous brief encounter in the back of a limousine between John Lennon and a severely under-the-weather Dylan reveals the Beatle at his most nervous and unsympathetic, and Dylan at his most “unwell”. This time, there’s little that is remotely charming, and the concert footage is presented as conflict. There is, of course, the slow hand-clapping and the infamous cry of “Judas!” at the Manchester Free Trade Hall but Eat The Document is complicit in the attack, with the loud, distorted footage of Dylan and The Hawks constantly interrupted by clips of British fans muttering their enraged verdicts (“He wants shooting. He’s a traitor”).

Perhaps understandably, the film has been criticised as an incoherent mess and yet it remains fascinating, capturing the quintessential Blonde On Blonde Dylan, all cheekbones, heavy lids, snake-hair and Carnaby Street threads. Dylan and – let’s call them The Band – are transcendent, and the narrative, while for some non-existent, actually tells a story.

Edited by Dylan and Alk – with rumoured help from Robbie Robertson – it is the ’66 tour through Dylan’s wired, paranoid eyes, an attempted journey, by train and coach, fractured by images of death and confusion, from the flat-capped evangelist carrying a sandwich-board quoting from Hebrews 9:27 (“It is appointed unto men once to die”) to a series of the same random images, repeated throughout the film: a beautiful woman staring, transfixed, at a hotel press conference; a decrepit old man smiling; a sandalled freak saying, “You’ve already asked me that.” The repetition’s effect is, as the film’s title suggests, that of the Ouroboros – the snake eating its own tail. If the first film warns us to not look back, Eat The Document tells us what will happen if we do – we will repeat ourselves.

Martin Scorsese used outtakes from Eat the Document for his No Direction Home film and the final question has to be, What haven’t we seen yet? Pennebaker describes a scene that’s not in the current edit he’s been working on or in Dylan or Scorsese’s films.

“I sat up one night with Bob and Robbie,” he says. “And in the course of that night they wrote 10, maybe 20, songs. They were just things that happened. They never became songs officially, as far as I know. And I still remember them and I recorded some of them.”

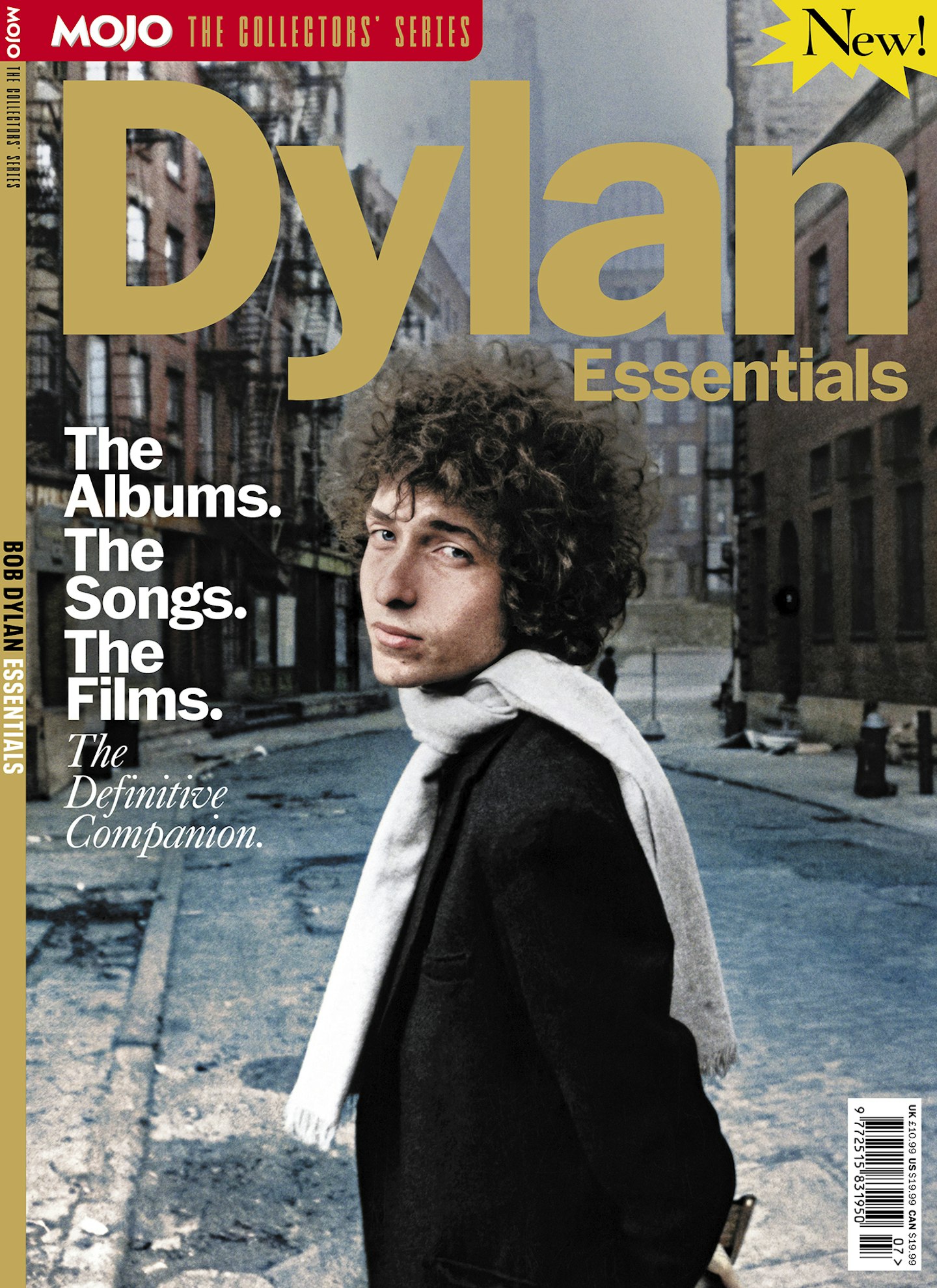

This article appeared MOJO The Collectors Series: Bob Dylan Essentials.