In 2018 MOJO found David Crosby on a roll – writing well, singing great and recording fine solo albums. It was a cornucopia of blessing he conceded he might not deserve. If only he could only have remembered to play nice with Graham, with Roger and with Neil, to name but three. “I don’t see any need to be gentle…” he told Dave DiMartino. One year on from Crosby's death, we revisit the interview in full...

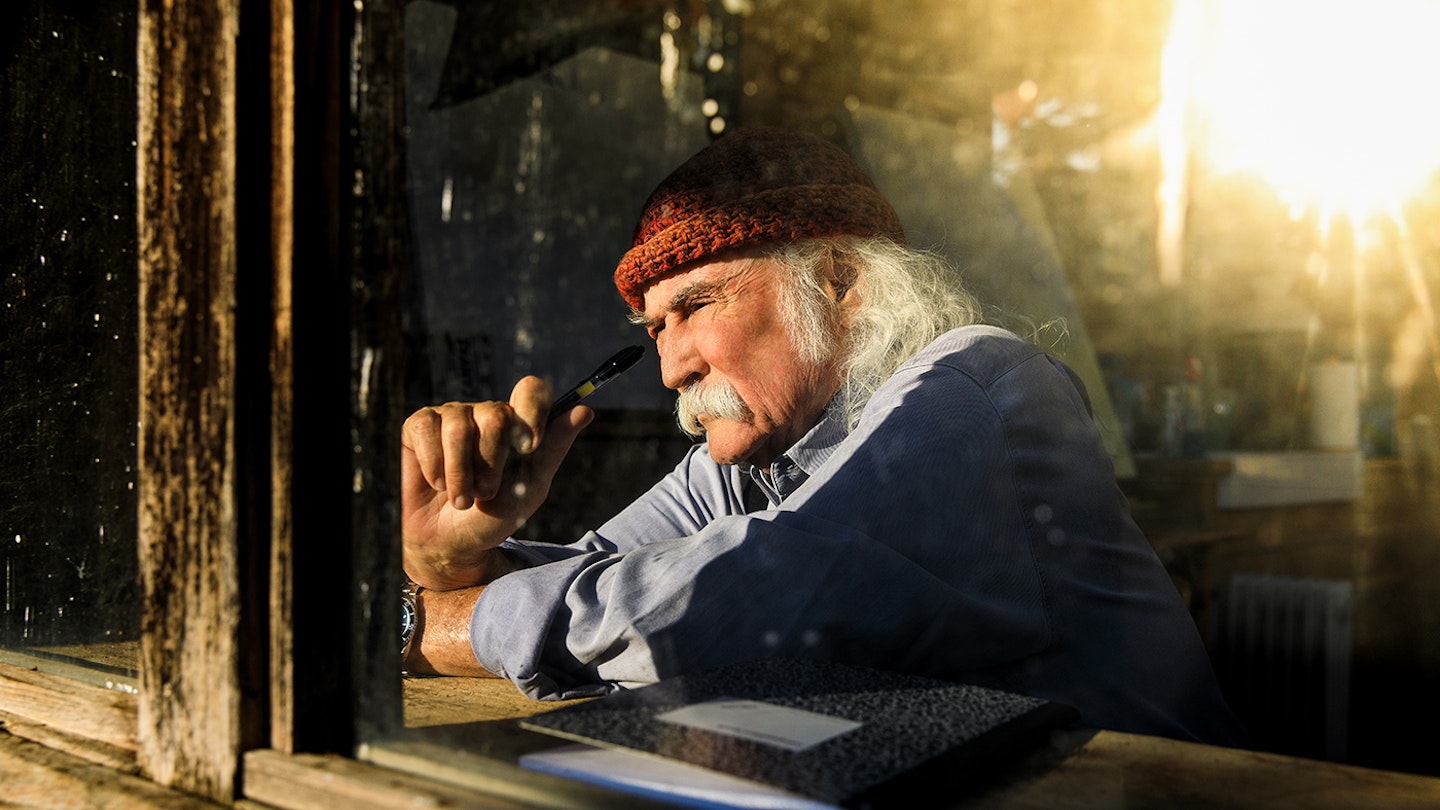

Portrait: Anna Webber

THERE ARE WAR STORIES AND THEN THERE ARE WAR STORIES...

“Let me swap with you,” says David Crosby as we choose our seats at the restaurant table, “because my left ear is my best one.”

Mine too, I tell him, switching seats. Filling a car tyre with air in the ’90s, it exploded, and there went my right ear, I explain.

“I know the deal,” says Crosby as we sit. “Mine’s Neil, Neil got me.”

Feedback?

“Well, just 130dB.” He smiles, thinly. “Him and Stephen. ‘I can play louder than you can.’”

We are having lunch at the Four Seasons Biltmore Resort in Santa Barbara, California, our table offering a splendid view of the Pacific at high noon: sun blazing, waves lazily rolling in. Crosby has learned to take the rough – shot ears, drug addiction, jail time – with this kind of smooth. Besides, he may just be having the time of his life right now. The 76-year-old has released four albums, each better than the last, in the last five years. He made them with two distinct, youngish bands, respectively dubbed the Lighthouse and Sky Trails bands. His latest album, Here If You Listen, arrives in October and is polished, timely, and politically challenging.

Most remarkable of all: his singing voice remains an object of wonder.

“Look, man, I did everything wrong,” Crosby says. “I did it all wrong. So there’s no excuse for me to be singing the way I am right now. I know that. My partners? My current partners that are so good I have to paddle faster to keep up? Those ones? They all tell me that I’m singing as good as I’ve ever sang in my life. And I don’t think they’re buttering my toast; they’re not that kind of people.”

But doesn’t age take a toll on every singer?

“Mostly what you hear, man, is hearing issues,” says Crosby. “Pitch is a feedback mechanism. In order to sing in pitch, you have to be able to hear yourself.” He starts warbling, deliberately off-key. “So when you can’t hear very well, you can’t sing in parts with other people very well.” He pauses for a beat. “Does that sound like anybody you know?” He smiles, a bit of mischief in the air. “I didn’t say any names.”

No, Crosby did not mention Stephen Stills, a man whose reliance on hearing aids is public knowledge, and, along with Graham Nash and Neil Young, his partner in the astronomically successful Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. Nor did he mention Roger McGuinn, whose hearing – we will hope – remains just fine, and who with Crosby was a founding member of the celebrated Byrds. But both performers and both groups came into David Crosby’s life early in his career, in the ’60s, when untold adventure, riches, fame and commercial success beckoned, and every arrow on every relevant graph was pointing upward to the right at sharp angles. For almost everyone.

For David Crosby? Not so much. Not everything came to a pleasant end. Despite his invaluable contributions to that golden stretch of Byrds albums from 1965’s Mr. Tambourine Man to 1968’s _The Notorious Byrd Brother_s, Crosby was booted from the band by McGuinn and Chris Hillman midway through the making of the latter – ostensibly for his insistence that the album include his song Triad rather than the Goffin-King penned Goin’ Back. It didn’t make it, and neither did he.

That was close to 50 years ago. Does it still disturb him?

“No, I gave up on that a long time ago,” he says. “It’s just egos. I was a very egotistical kid, and I was trying to get all the attention I possibly could, and I wanted to be more than just the rhythm guitar player and harmony singer, I wanted to sing lead, I wanted to play my songs. And there was ego friction, between me and Chris, me and Roger, and me and Gene [Clark]. It’s just the same thing that happens in all the bands.”

If Crosby was looking for a smoother ride or more indulgence of his songwriting, he could barely have chosen a more problematic vehicle than CSN or CSNY. Although the internal rivalry fueled some of Crosby’s greatest songs: Guinnevere (later covered by Miles Davis, no less), Long Time Gone, Almost Cut My Hair…

“It was an intensely competitiveenvironment,” Crosby recalls. “Intensely competitive. When it got to CSNY, fully competitive, all the time. We liked each other a lot at first, we transcended our egos for quite a while there, and made some very good art. But like all bands, it goes downhill after a while.”

Crosby is thankful for those early days, but it’s interesting that he describes them in terms of an apprenticeship rather than a pinnacle.

“They gave me a platform to get good,” he says. “The Byrds and CSN and CSNY gave me a shot at having the tools to work with. And in Nash, an incredible harmony singer; in Stills and Young, incredible writers and incredible guitar players. They had a lot to give. Roger McGuinn was at least half of what happened with The Byrds. Credit where it’s due, man. Those guys gave me music to work on that was spectacular. Stills’s songs? Are you kidding me? Those rock‘n’roll hits that we had? A great platform to learn on, great bands to be in.”

So is there anything he wished he’d done differently?

“What could we do better? Lose our egos. The same thing happens to all bands – if you’re in a marriage with somebody and you’re not in love with them, they irritate you. And I’m sure I irritated the shit out of them. I became a junkie. That let them down pretty badly. But we’ve all done horrible stuff to each other – Neil leaving Stephen on tours, like three times, in the middle of a tour, that’s pretty grim. You don’t do that. We’ve all done horrible stuff to each other. Really horrible stuff.”

If I Could Only Remember My Name: David Crosby's masterpiece revisited.

“Music pinned me to the map…” David Crosby reflects on his life in music.

The horrible stuff would get worse, not better, for David Crosby in the years that followed. Most, but not all, was drug related, In 1982, he spent nine months in a Texas state prison for possession of heroin and cocaine; in 1985, he drove into a fence in Marin County and was arrested for drunk driving, possession of cocaine, drug paraphernalia and a concealed pistol; in 2004, hotel employees searching his suitcase for identification found pot, rolling papers, two knives and a gun, for which he spent 12 hours in jail before being bailed out and, ultimately, fined $5,000.

If I had the choice of going on as a junkie or going back to prison, I’d go back to prison in a second.

David Crosby

Today, Crosby harbours no romanticillusions about this part of his life, and recounts it matter-of-factly.

“I made every mistake possible, all of it,” he says. "I went right down the tubes until I was a junkie. It doesn’t get any worse. Freebaser and junkie. I was as bad as it gets.”

Was there anything he might have done to avoid going down that route?

“No,” he says emphatically. “It only goes four ways. You die, you go to prison, you go crazy and you’re incarcerated, or you quit. Those are the four options. There are no other options. So I lucked out. I went to prison. That changed it all. All of a sudden I was no longer destroying myself, I was rebuilding myself.”

So jail was a positive?

“Absolutely. If I had the choice of going on as a junkie or going back to prison, I’d go back to prison in a second.”

Did you have a hard time in there?

He nods.

Being the rock star?

“It’s not a vacation spot, man. They mean it to be hard. And they’re assholes. And it was Texas.”

Did you reach the point, when you were at your worst, where you thought, I’ve lost it, I can’t make music any more – that’s it?

“It’s a plottable curve.” He draws an imaginary graph in the air. “You take my drug use – as it increased, writing went down. Same rate, same curve. Ovular. Drug use peaked, stopped writing. You can only draw one conclusion from that. When I quit, when I went to prison and was forced to quit, the writing came back.”

He looks out at the Pacific in front of us. “I lucked out, man.I just lucked out.”

In many ways, David Crosby did indeed luck out. First and foremost, there has been a constant in his personal life for an unusually long time: his wife, Jan Dance.

“We’re very close,” he says. “We’ve been together 41 years. She’s very patient and very strong, and our love for each other is very strong. We are, neither of us, perfect at all. But she’s a wonderful girl and I wouldn’t be alive without her. I would not have made it through the junkie part of it if I did not have what the French call a raison d’être, a reason forbeing. And for a time there, she was my reason for being.”

If a life can indeed be plotted like a curve on a graph, let’s acknowledge that Crosby’s has been on the rise since the mid-’90s. In fact, pencil in February of 1995 as one especially noteworthy co-ordinate; that’s when Crosby, for the first time, met his son James Raymond, who’d been given up for adoption by his mother in the early ’60s. Raymond had heard Crosby was recuperating from liver failure, and had received a transplant months earlier. So son came in to meet father at the UCLA Medical Center.

“Normally,” Crosby says, “when you meet up with a kid that was put up for adoption by his mom like that – that you’ve never met – it doesn’t go well. Normally, everybody coming to that meeting brings too much baggage. Too much, Why did you leave me and mom? We weren’t good enough for you? Attitude, baggage. He didn’t do that.”

That initial meeting took root and affected both Crosby and Raymond profoundly. Raymond, then 35, was already a skilled musician – he played keyboards and favoured funk then – and with the addition of session guitarist Jeff Pevar they would become Crosby, Pevar & Raymond, or CPR. In 1998, CPR released the first of four albums. The music was strong, the new bandmates impressive, and David Crosby’s career was on the upswing.

“James gave me a chance to earn my way in, be his friend, and I’ve written a lot of the best music of my life with him,” says Crosby. “He’s a much better musician than I am. But when we butt heads musically, I submit to him – because he knows way more than I do. We have a good relationship here. We’re working on the next record. There’s going to be five in five years. We are writing another one as we speak.”

Crosby’s musical enthusiasm doesn’t stop with his son. A 2015 appearance on Family Dinner Volume Two, a benefit record put together by US jazz rock band Snarky Puppy, led him to a productive union with an entire cast of skilled players and friends, in which several members of his two current bands have roots. Among them, producer/player Michael League, keyboardist Michelle Willis and guitarist Becca Stevens comprise the Lighthouse Band, who recorded the upcoming Here If You Listen; Willis, Raymond, Pevar, bassist Mai Leisz and drummer Steve DiStanislao are among those in the Sky Trails Band, who accompany Crosby on his European Tour this month.

“These people got me so excited,” Crosby notes. “They’re such a joy to work with – these are people who are young, and thrilled, still, with music. They’re not jaded at all. It’s encouraged me so much. That’s the only explanation I can come up with for four records in five years.”

Of course, David Crosby’s visibility has been further enhanced lately by his presence on Twitter – which is biting, hilarious and candid. The cliché is that as people get older, they don’t care so much about what people think about them. Crosby appears to have passed that point long ago.

“A long time ago, yeah. Well, if you have to live your life in front of the entire world, and then you fuck up a bunch, in front of the entire world, and then you have to put it back together again, in front of the entire world, you become desensitised to the approval factor of the entire world. It no longer has the same punch.”

There would appear to be few sacred cows in David Crosby’s world. He’s criticised his CSNY bandmates Neil Young and Graham Nash when both left their wives of many years for younger women, leading to serious fallout. Then there was Kanye West. “He did that really awful Bohemian Rhapsody [at Glastonbury, 2015] and came off afterward and said he was the ‘greatest living rock star’. So I said, ‘Listen, if he thinks he’s the greatest living rock star, would somebody please drive him over to Stevie Wonder’s house so he can see what the greatest living rock star actually looks like?’ And while you’re at it, could you buy him some Ray Charles records so he can learn how to fucking sing, because he can’t sing, write or play. He’s a fucking poser.”

People are sometimes too careful; they don’t want to say the wrong thing, I note. “I don’t buy that. I talk about people who can really do it. I applaud Joni Mitchell – I know she’s crazy, I know better than anybody else, she was my old lady. But man, she was the best – she was the best of us. And I’m not going to shut up when somebody says… somebody was trying to say that Yoko Ono was a legitimate artist, and I said, ‘You’re out of your fucking mind – I’ve heard better music out of an air raid siren.’

“I do go off on people sometimes when it’s an extreme case. What I try not to do is for some kid who’s saying, ‘Will you listen to my brother’s band?’ or, ‘I just wrote this song, it’s really emotional for me. Could you, like, tell me if it’s any good?’ Well, I try not to rip their heart out, because you need to be a little gentle there. But I don’t see any need to be gentle with, what’s his name, the really right-wing guitar player?”

Ted Nugent?

“Ted Nugent. I don’t see any need to be gentle with Ted Nugent.” He laughs. “He’s an asshole! It’s a slippery slope.”

If there is one area where some sensitivity is noticeable on Crosby’s part, it might be the event which took place in nearby Los Angeles the previous night and will again later tonight: The Sweetheart Of The Rodeo 50th Anniversary performance starring Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman. Released in 1968, Sweetheart… was the first Byrds album on which David Crosby did not appear. And he wasn’t invited to this event, either.

I assume he felt a twinge?

“Yeah, of course. I’ve been trying to get Roger to get The Byrds together for years. I ask him about once a year, and he still says no.”

It seems like you have a friendly relationship with himon Twitter. “We are friendly,” he says. “But he doesn’t want to work with me, so that’s a shame. I think Roger is an amazingly talented human being. He seems on the face of it to be kind of stuck in a folk singer thing, but when it came to translating Bob Dylan’s songs into records, he was a freakin’ genius. And I would work with him again in a minute, if he would.”

I have apologised to Neil for slagging his girlfriend. I don’t think that’s what’s really going on.”

David Crosby

From which an inevitable question arises. With McGuinn, with The Byrds, with his bandmates in CSNY, does he notice a pattern in his behaviour? In their behaviour? Has it been a process of people coming back and apologising? Of asking to be forgiven?

“We all have, many times,” he says. “And I have apologised to Neil for slagging his girlfriend [Daryl Hannah]. I don’t think that’s what’s really going on. Neil has only really worked with us when he thought he needed us. We’re part of a plan. Neil has a plan. And when he needs us, he’ll call us up. Now, he doesn’t need us. He’s filling big places by himself. He’s got a band that he’s got on salary. That’s a good band. I’ve seen a tape of him playing with that band where he’s playing as good as I’ve ever seen him play, ever. Doing Cortez The Killer and fucking nailing it. Put all those things together man in your head and ask yourself is he going to call us up and get into a bundle of… I mean, it’s like a fucking… therapy

session, trying to get us to talk to each other. Why would he bother?”

That said, how things worked out with Graham Nash – “I don’t want anything to do with Crosby at all,” Nash told a Dutch magazine in 2016 – did seem unimaginable, considering the pair’s long friendship. I felt bad about that, I tell Crosby.

“Me too,” is his only reply.

But David Crosby doesn’t want to wait. “If they’re mad at me, they’re mad at me – I’m sorry,” he says. “But I still can’t sit around praying for them to change their mind. I have to make music now, while I can. I don’t have any bad feelings in my heart about any of those guys. I would work with any of them at any point. Roger McGuinn, Neil Young, Stephen Stills, Graham Nash, I would work with any of them.”

Meanwhile, Crosby’s current run of solo albums reveal him as the one – of all the icons of the Woodstock generation – who’s nearest the top of his game. How unlikely is that?

“I was supposed to be dead 20 years ago, and I’m not,” he says. “I was supposed to be dead from being a junkie. I was supposed to be dead from Hepatitis C. All that stuff was supposed to kill me I was supposed to die in prison. And I’m here. So I’ve got this opportunity. I have this thing I can do where I can actually make a contribution. I’m not just sitting on my butt, I can actually make things a little bit better by making music. It’s the only thing I can do that does that.

“And it matters to me, a lot. Because I’ve spent a lot of my life just being a wastrel, just trying to see how much pleasure I can cram in. So to now feel that I can make a contribution? If I feel I can, I think I absolutely should. So that’s what I’m doing.”

This article originally appeared in MOJO 299.