In 2007 Led Zeppelin played what is widely regarded as the gig of the century. Five years later, as the band prepared to release Celebration Day, a document of that legendary night in London, MOJO invited Jimmy Page, Robert Plant and John Paul Jones to take us backstage at the O2 and to lay bare the truth behind what happened next. As part of MOJO’s own celebrations to mark 30 years of the world’s finest music magazine, we’ve revisited the interview in full…

December 10, 2007, The O2 Arena, London

The lights go down and, as the arena fades to black, a television screen above the stage crackles into life to reveal a clean-cut, bespectacled American newscaster, hair parted to the left, wearing a blue-grey suit and a long-collared shirt. He is Scott Shuster and he transports us back to May 5, 1973 – the day Led Zeppelin drew “the biggest crowd ever assembled for a single performance in one place in the entire history of the world” at the Tampa Stadium, breaking the record set previously by The Beatles. Up flash the numbers: 56,000 tickets for the Tampa show, yielding $309,000 versus $306,000 grossed by The Beatles at Shea Stadium eight years earlier in front of a slightly smaller crowd. In the summer of ’73, Led Zeppelin truly were the biggest band in the world. Tonight in London, with Paul McCartney watching on from the gods, they are once again.

I HEARD there were 20 million fans that applied,” says a disbelieving Jimmy Page speaking to MOJO a few weeks before the O2 show, referring to the online registration and lottery system used to distribute the £125-per-head tickets. Held as a tribute to Atlantic Records boss and Zep acolyte Ahmet Ertegun, who died at the age of 83 following a backstage fall at a Rolling Stones concert at New York’s Beacon Theatre in 2006, tonight’s show is nominally a multi-artist bill. But the 18,000 ticket holders packed into the venue formerly known as the Millennium Dome are only here to see one act.

To say that the level of excitement is palpable is an understatement. The air is alive with fan-chatter, a sense of uncertainty and a raft of questions: with his fractured finger, leading to the show being postponed from November to December, how well will Jimmy be able to play? Will Jason Bonham cut it compared to his late father John? Will he be able to recreate that vital rhythmic chemistry with John Paul Jones? Can Robert Plant still hit those high notes? Will the show rise above previous ill-fated reunions like the debacle of 1985’s Live Aid and the rusty Atlantic Records 40th Anniversary? And, simplest of all, what the devil will they start with?

In a pitch black arena, Jimmy Page provides the answer to the latter via two trenchant barre chords, underpinned by rhythmic strikes from Jones and Bonham as the stage slams into life with Good Times Bad Times – a surprise opener which Zeppelin never actually played live in its entirety in their 1969-77 heyday.

“In the days of my youth, I was told what it means to be a man! Now I’ve reached that age, I’ve tried to do all those things the best I can!” wails Robert Plant. His vocals are noticeably lower than on the recorded version on the band’s debut album, adding nobility and gravitas to the lyric’s reflective sentiments.

The track ends with a modicum of uncertainty, Page, Plant and Jones triangulating around the drum kit and looking at Bonham for their final cue. The nervous energy that spreads from the musicians into the audience during the thunderous first track is becalmed by Page’s strum of the opening chords to Ramble On – another track previously unaired in full until now, and where tonight the intimacy of the ensemble playing is matched by Plant’s measured, emotional vocal. The celebratory romp of Black Dog follows, with a beaming Page dancing in time to the groove and Plant sharing his call-and-response vocal with the audience.

Jones straps on his fretless bass and Page turns to a Gibson semi-acoustic to deliver a brutal In My Time Of Dying, Plant’s vocalising combining with Jimmy’s slide work as Bonham adds to the music’s heft. “This is our first adventure with this song in public,” announces Robert Plant as Page strikes up the riff to For Your Life, the band’s lyrically scalding commentary on the LA coke scene. Another tune previously unaired on-stage, its inclusion is startling bearing in mind that the track was recorded in late 1975 and included on Presence – an LP made when Plant was convalescing from a near-fatal car accident on Rhodes and Page, by his own admission, was in the grip of addiction. Tonight, however, the past is almost rendered irrelevant by a heroic, urgent, utterly transfixing performance. Material such as Dazed And Confused (wherein Page retreats, bow-in-hand, into a laser-generated green pyramid to create a tenebrous atmosphere) and a richly textured Stairway To Heaven which moves with both grace and increasing power) is undoubtedly classic, yet is delivered with an inventiveness and authority that brushes aside any sense of nostalgia. Nowhere is this more evident than on the monolithic reading of Kashmir in which Plant finally appears to lose his inhibitions. “Phenomenal!” is how Page will later describe it.

The encores are emotional high points: a frenetic A Whole Lotta Love is followed by the victory procession of Rock And Roll, after which a drenched Page, his white shirt sticking to his torso, seems to kiss his guitar before gathering round with Jones and Plant to applaud a beaming Jason in front of an ecstatic crowd that in places appear emotionally overwhelmed. To MOJO’s right a couple are weeping. The gigantic Led Zeppelin logo that illuminates the stage appears to announce the return of the most formidable rock’n’roll band of all time. Few would guess that it could signal the end…

Robert Plant: "When it finished I got out of there and ended up in The Marathon Bar in Chalk Farm."

I didn’t think anything of it right after the event, but we actually put right all the kind of fuck-ups along the way. Live Aid, Atlantic 40th…” begins Robert Plant, eschewing small talk to launch straight into a discussion about the O2 show.

Holding court on a warm day in late September 2012 in the top-floor dining room of a pub in Primrose Hill, the 64-year-old singer is the first of the three surviving members of Led Zeppelin MOJO will quiz about the events of five years ago.

According to his publicist, Robert has put an inglorious 20 minutes aside for our discussion, suggesting Plant is a less than willing participant. As it transpires, our time will over-run with ease and without interference, the singer talking with enthusiasm and peppering his conversation with riddles of his own making and the odd moment of obfuscation.

Over the past five years, Plant has concentrated on his solo career. In the wake of Zeppelin’s return he scooped a raft of Grammys for Raising Sand, the 2007 album he recorded with Alison Krauss. Despite that success, a second album with Krauss never materialised. “With the people I was playing with there was maturity and workmanship that was totally different,” he explains. “That said, you could go mad if you got stuck in that for too long because it’s workaday.” Instead of resurrecting his partnership with Krauss he formed the Band Of Joy (confusingly named after his original ’60s outfit) with Americana veteran Buddy Miller and Patty Griffin, and he has emerged latterly fronting the “totally wild” Sensational Space Shifters.

For all his current endeavours, Plant admits he enjoyed watching Celebration Day and he smiles broadly when MOJO offers our approbation, having been treated to a special screening at London’s Soho Hotel with director Dick Carruthers the day before.

“The great thing for the three of us and Jason – and probably because of Jason – was that it really did work,” he smiles. “We were able to creep up through the undergrowth of all the ensuing years and peek through and get back into it.”

Did Jason bring the three of you closer together?

Yes. There was nothing prickly or spiky about Jason. His enthusiasm has always been phenomenal… about almost anything! (Laughs) Sometimes it was artificially inspired, but not now. I’ve known him since he was about 18 months old when John and Pat [Bonham] were living in a caravan behind her mum’s shop in Redditch. We go back a long way.

I’ve got used to Jason’s fantastic bludgeoning of my senses all the time about one thing or another, but he’s brilliant. He came to the rehearsals without any of the trappings, except for the fact that he’s historically obsessive which to me is such a yawn. I mean, who cares what the fuck the difference is [in the set] between Night One somewhere and Night Two somewhere else? You just play it and then you go away.

Zeppelin fans can be trainspotters…

Yes. And if you’re musical, then that’s fine but I’m not. I’m a singer. My adventures with Led Zeppelin are pretty interesting because I’m kind of like a… or I was… like a glider pilot, or a moth. I just kind of land in the middle of something very pretty and then take off again because most of it, construction-wise, is built on a musicality. To make songs in the middle of it all was wonderfully challenging, and so it was on that night. There were songs where my appearance was important but it had to be right. It wasn’t about “bare-chested, flaxen-haired marauder arrives on the scene in bar 99”. It was more like, “Get in there, Planty! Quick!” Jason’s point of view is microscopic which, in its own way, is brilliant. He brought in lots of anecdotal bits and pieces that softened the environment as we worked together.

There’s always been tension between the members of Led Zeppelin. Why?

Yeah, well, I think it’s because we’re really good. Being really good means that nobody should dominate and everybody wants to get their point across, or everybody wants it to go in a particular direction. That’s probably one of the reasons why I’m very happy moseying along heading for Brazil next with the Space Shifters, because it’s a big ask to be part of something like that, especially when you’re in your sixties or even your forties. It’s a magnificent beast that was because the musical options were so amazing. There was so much… not knowledge… that’s not the right word… but derring-do in those days. It was interesting because when Lydon and the guys appeared in ’77 or ’76, we were proclaimed obsolete, but what had actually happened was that we were spreading ourselves thinly all over the place, and then actually also wanting a life because we were that much older… but not that much older, in reality.

You were 32 when Zeppelin split…

Yeah. So, we were always capable of interesting things but we had to interest ourselves primarily. There was no great need for it to be anything more than that. That’s why the O2 thing was such a… I mean, when it finished I quickly got out of there and I ended up in [late-night kebab shop] the Marathon Bar in Chalk Farm.

What were you running away from?

I just wanted to go somewhere and have six bottles of Keo, half a bottle of vodka and wake up in another world because the patronising and the momentum that was gathering around – the speculative stuff – was getting in the way. Jimmy said, “It’s just getting in the way of what we’re doing.” It was never like that when you played the Fillmore in a matinée on a Saturday afternoon.

The great thing now, later on in my time, is that it’s about a different energy. It’s just as creative but the expectations are different and it allows me to be dignified in what I do for myself, and within myself. But [the O2] was quite a thing for us to experience because our primary objective was to say: Ahmet fell over at a Stones gig, what a fucking drag. I got to know him more and more but in the Zeppelin years we had so much fun with that guy – all the way through our time Ahmet had been there or thereabouts.

There had never been some kind of crusty moment where it felt that you were dealing with a potentate who had whistled the solo into the ear of the tenor player on Little Egypt during one of The Coasters sessions, or been mouthing into Ray Charles’ ear during Mess Around. You could just talk to him about music the whole time.

When I was doing The Honeydrippers stuff he said, “We’ll get [Louisiana musician] Tommy Ridgley and Charles Brown is still playing great piano in Chicago.” I said, “No, no, no! This is a white kid – who is overtly white – who’s just trying to meet Wynonie Harris halfway so don’t bring all this shit in!” So instead [of prolonging the conversation] we went out to some club with Phil Spector to see Barney Kessel. The three of us were standing at the back of the club – I think it was the Bitter End, or the Blue Note – and we were talking about the outro to Gene Pitney B-sides, Town Without Pity and shit like that. Everybody was looking at us going, “Shhhh! Shhhh!” Barney Kessel was up there just playing with his little dickie bow on. Ahmet was just arguing about music and using these mannerisms that I noticed in 1969 when I didn’t know him very well. He had these droopy eye-lids, and a look that told you he was up to no good. Of course, there are people who saw the other side of Ahmet, but to me he was unique.

So, the many great moments that led up to the O2 from many years before, the moments that really inspired the O2, flashed through my mind on the night and it was very emotional.

"That was the whole thing about Led Zeppelin. There were fantastic musical interludes where I had no part to play. "

Robert Plant

Were you nervous before you went on-stage?

Oh, yeah. Of course I was.

What were you doing just before you went on?

Actually, I was trying to be in a room on my own but I was going to John’s mum, Joan… (laughs to himself with glee) and to Pat and [daughter] Zoe and that, and I was saying, “Now look, the boy [Jason] is going to be fine. Leave him to me.” I had this abject semi-uncle role I’d taken on ages ago. I gave them all a hug and I sat alone for a few minutes and I thought about what it took to get there, and how getting there was such a different place from the one I’d wanted it to be.

Did you feel you were leading a double life at the time?

Yeah…

From promoting Raising Sand, suddenly you had to unleash the Golden God…

Yeah, but I wanted to do it right for my time. I knew about that other guy but I’d had to wave him goodbye. The last pair of leather trousers went to Oxfam a long time ago. So I had to take on the idea of a guy at the front of the stage for several minutes, looking interested, but not singing. That’s the whole thing about Led Zep; there were fantastic musical interludes – when the wind was with us – where I had no part to play. It seemed that with the momentum of the old times, the expectations were different. The crowd was a different crowd, there was a different animal in front of us. So it was a different place for me to be in during the moments when I wasn’t involved.

I’ll be in Rio in two weeks’ time with the Space Shifters with Juldeh [Camara] playing a one-string ritti and Johnny Baggot from Massive Attack creating loops and maybe a bit of dubstep in the middle of it all. I’ll be having a great time because there I am occupied. I’m playing bendir or doing whatever. But, there, on that night, I had to go back into it in a different way, whereas Jimmy played spectacularly, in another world, another time. But those guys are moving the thing and I am kinda landing on it, which is a strange and different role for me now. So how could I go there on that night? Because I want to do lots of different things.

On the night you adapted your singing style. It didn’t feel as if you were singing the songs the way you had in the ’70s…

It can’t be that way. It had to be an appointment you made with your past…

The past appears to weigh heavily on Robert Plant, more specifically his past with Led Zeppelin. “It asks so much, it expects so much of you,” he says of the band, before admitting that he is fixated with the idea of constantly making new music. “It’s about trying to move in and out of different zones,” says Plant. “Then you can say you truly have a life in music.”

“I’ve just written 13 new songs with Buddy Miller and Marco Giovino which sound like Amadou & Mariam go and see fucking Public Image Limited!” he declares later during our conversation. When MOJO says that this sounds scary, Plant looks slightly hurt and counters, “It’s great!”

The day after our conversation, at a press conference held to launch Celebration Day in London in front of 200 members of the European press, Plant will return to his uneasy relationship with the past, stating “we come from a different time”.

What bothers you about your past? Is it the clichés associated with the band…

…Yeah, absolutely…

…Because people seem to have taken what Zeppelin did and…

…And they missed the point. They totally missed the point. Page and I were in Bombay in whatever it was, ’71 or ’72. We’d made our way through Thailand. We’d been up to no good and that was our job: to get up to no good and gradually make our way home from wherever we were. Through George Harrison and the government of India Film Department we got this crew of Indian musicians and we recorded versions of Friends and Four Sticks, and it’s a great bootleg. What’s great about it is that we’re giving it some from another angle, and that’s how everybody’s got to be, because there’s more gifts in the work of a pattern-maker or, you know, a guy in a body shop than there is in a guy who fronts a rock’n’roll band if that guy does the same thing all the time. It’s so mind-numbingly dull, the expectation that anybody should do that in character forever. When Zep was creative, it was worthy of everybody’s time. That has to be a code of practice for everybody that’s a musician. You have to do something that people don’t expect.

Is Zeppelin not a vehicle that is so free that you can express yourself in any way that you want?

I would think so, yeah.

Then why not continue to do it?

Well, where does it begin? That night there, at the O2, I was amazed at how great it was and how strong it felt. I thought it was amazing, but it wasn’t kind of me. It was an adaptation of me… It was me going somewhere else and going, “Yeah, this is great! What we need is some new shit!” But old blokes making new shit needs to be – woah! – way over there.

You tried new things at the O2, songs that you hadn’t done live before, like For Your Life – a song that you recorded when you weren’t in the great shape, to be honest…

No, I was in a wheelchair but I was in better shape than everybody else.

So why choose that song?

Because it was important. It was important lyrically to me, believe it or not. It was important for us to do something new. I was willowing on saying, “Can’t we end the show with ‘Goodnight– I was walking in Jerusalem just like John’” [from The Incredible String Band’s A Very Cellular Song] because Jimmy and I had always said, “Can’t we put everything down at the end of Kashmir or whatever and pick up some instruments and play this la-dee-dah?” And, of course, we couldn’t because the forces that be, the expectation is that you can’t veer off too much left or right.

Who are those forces? Managerial? Or…

No, no, no. It’s just [people who say] “What the fuck is that for?” We used to used to lie down and do the dying fly on-stage from Monty Python [UK TV show Tiswas, surely? – Ed.]. We did that when we did Earls Court in 1975, and once we started the Forum [in Inglewood, California] with an instrumental, Perfidia by The Ventures (sings the guitar line). You know how quickly 18,000 people can really be not very happy (laughs)? It was fantastic! But then there was bottle. We had bottle, we didn’t give a flying fuck. It was great!

I think that later that night I stood in a tree and declared I was the Golden God because Moonie and Roy Harper had driven a car between two palm trees and couldn’t open the fucking doors to get out. George Harrison had karate chopped Bonzo’s wedding cake or 30th birthday cake or 25th birthday cake at some party and Bonzo decided it was time for George Harrison to go into the swimming pool. We were children! And there was some vaginal relaxant for cows somewhere being inhaled by somebody. You want to know about what it was like? It was fantastic! Insanely gorgeous! There’s a headline: It was insanely gorgeous! But what now hovers over London like a sort of I-Married-A-Monster-From-Out-Of-Space is not the same thing, neither can it be.

The legacy seems to weigh on you all

Listen, in the Labour clubs in the Black Country ’round Wolverhampton on a Saturday night when I was bit younger (coughs ironically), I used to play in a group and after about half an hour they’d start shouting, “Fuck off! Go and get a hair cut and a proper job!” and then they’d have [music hall-styled sing-along known as ] a free- and-easy and somebody would play the piano and sing He’ll Be Coming ’Round The Mountain. You’ve got be careful that the whole thing doesn’t become a free-and-easy. You can’t keep going back and tugging at the old tunes in the same way with the same shoulders. It’s the shoulders. If so much is expected, we did what we had to do.

The lean of your conversation is like, “Why not keep doing it?” The thing is that everything that we did back in those days and everything that I’ve done since has been based on a fresh approach. What’s going on? What can I be as a singer that doesn’t play much? That’s how I see everything: what can I be a part of that’s exciting? And if anybody’s got any ideas I’m always up for it.

I sang a bit on the [new] Primals stuff because I think their references on looking back on the glorious past and the way they bring them into the contemporary world is great. I know Jonesy has got some great ideas and I believe Jimmy has too, but we’re here talking about a film we didn’t even believe was going to be much good, and didn’t want to see. “Oh, it was filmed too?!” I didn’t remember it. I just know the repeat on No Quarter didn’t come in on time (sings) “The dogs of doom are howling more-more-more” Oh, it’s wrong. That’s why I went away to The Marathon Bar and went “That fucking echo!” And that’s all I thought about for two years, “Oh, yeah, the echo was wrong.

Honestly, no one gave a toss about that…

I did.

So what did the entire experience teach you about yourself?

Well, doctor… (laughs) What did it teach me about myself? I think it meant that I had fortitude and could fit in without going into panto because, as I said earlier, it is instrumentation that primarily moves everything. It is about the dynamism of those guys, what they can play and how they play it. It taught me… (pause) I wasn’t waiting for a bus, I was having a great time! (laughs and pauses)… and I was admiring!

I’m not going to ask you if you’re going to do it again – I think you’ve answered the question…

Well, you know, everything’s in the air, isn’t it? Five years later a film comes out. Ten years later there might be a book of the film of the T-shirt. I love what we did. I also have to say let’s not forget Carruthers’ work and diligence. There’s nothing cut out of that film. It’s the set from start to finish, you know. Maybe the vocal was flat on

a couple of songs and he tuned them up, I don’t know. When it gets to Since I’ve Been Loving You or No Quarter or something like that, [the film] moves with what the music would require. You can’t knock it, really.

MOJO’s audience with Plant ends with the man gripping our hand firmly. He offers a few chiding words about the mentions of the past before admitting “I did actually have a wonderful time at that show.”

John Paul Jones: "I seriously doubt we'll play together again. I’ve always said never say never but I can’t imagine it."

Five hours after sitting down with Robert Plant, MOJO arrives at the Connaught hotel in Mayfair to speak to Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones. The latter is housed in an airy suite on the fourth floor that seems overrun with books on contemporary design. As ever, there is nothing flash about Jones – the former session man who told MOJO in 2006 that he initially thought Zeppelin would last “two or three years” after which he would get back to “a serious career in the studio”.

Of all the members of Zeppelin, Jones is arguably the most active as well as the most discreet, playing with a myriad of musicians from varying genres ranging from blues (he played on Seasick Steve’s 2011 album, You Can’t Teach An Old Dog New Tricks) to hard rock (Them Crooked Vultures). Currently, he is preparing to tour the UK in November with Scandinavian jazz-noise outfit Supersilent and is working on an opera based on August Strindberg’s Ghost Sonata set for 2015.

“I’ve been quite busy recently,” he admits. “I did Africa Express the other day with people like Rokia Traoré and Fatoumata Diawara, and I did the Sunflower Jam as well with Alice Cooper, Brian May and Bruce Dickinson.”

MOJO admits to having seen photos from the latter charity show, most notably of Jones playing a cowbell. “Well, there were two bass players already on-stage so I got a cowbell instead,” he says. “For once, though, I did manage to get some light on me on-stage. Mind, you there’s another shot of me with Ian Paice, Brian Auger and Brian May, I’m in the middle and I’m in total darkness and they’re all in bright spotlights. So nothing has changed at all, except in the film where I’ve got light!”

It reminded everybody what we were. Obviously there’s no Bonzo, but it’s bloody close to what we did.

John Paul Jones

Back in 1994 Jimmy and Robert worked together as Page And Plant but you weren’t involved. You said you felt “betrayed”. In the wake of that, were there situations to work through before you re-joined Led Zeppelin?

(Pause) It’s the first time I’ve actually thought about this… but in the Zeppelin days, one of the reasons that it was always good was that we never brought anything personal on to the stage. Never. Even if we’d been screaming at each other all day we’d get on stage and you’d just get into the music and give it everything. And it was the same this time. I can’t say we’ve ever had a social relationship. It’s not like we see each other or lived with each other like bands like Traffic did. We always had a very professional relationship so it was easy to slip back into that without even having been as close as we were. It felt like, “It’s Zeppelin time again, let’s do it!”

You’ve played with Jason Bonham in more informal situations, but how was it sitting there this time comparing him directly to his father?

We weren’t comparing him directly at all because we were concentrating on the music. If he did something that was not right for the music we’d say so but he generally had a pretty good feel for it because he’s lived and breathed it! (Laughs) Plus, he had this great encyclopaedic knowledge of it. He was like the band Google, really. As our sets list changed over the years, songs would end differently or segue into something. We’d be playing something [in rehearsal] and go, “How do we end this?” and he’d go, “In 1971 you did it this way, but it ’73 it had changed to this.” It saved a lot of time.

So when you got to rehearsals what was the first song you played?

You know, I’m not sure. It might have been For Your Life. I do remember sitting there and saying “I don’t remember what I played on this.” Then I realised that was because we’d never played it live.

The set started with Good Times Bad Times – another song you hadn’t played live a lot…

No, we hadn’t. Only later did I realise how difficult it is to play! I was thinking, “Whose bright idea was it to start with this? Oh, it was mine!” (laughs).

So when you got up there and you were looking for a bit of comfort, it could have got either way.

Yeah, but the amount of work we put into it, no it couldn’t. We couldn’t turn up and go, “Well, we haven’t played this stuff for almost 30 years but we’ll do our best.” We couldn’t do that. It had to be not only good but also of the moment, as if we’d played it back in day but with the ongoing electricity and energy.

When it comes to No Quarter, your solo that night was completely different. How do you approach reinterpretation?

The only way to approach it is to never play anything the same way twice. Never. People used to say, “Stairway To Heaven? How many times have you played that? Don’t you get bored?”

I would say, “No, every time I approach it, I approach it as if I am playing it for the first time.” I try and find something new, something to keep it breathing. A different approach, different rhythm, different accents. The Song Remains [The Same] is a good example. I play a whole bunch of different stuff on there that I’ve never played before, even in rehearsal, because that’s how I do it for me.

I also go back to what I think the music is about in the first place. On the night I kept things relatively simple because towards the end of Zeppelin I was getting a bit too complicated. The weird thing was that you have this mental process that’s going on all the time where you make notes to yourself. It was in Kashmir or maybe No Quarter, I can’t quite remember, and I played something and thought to myself, “I won’t do that tomorrow night”! And then it was like, “Ah…” (laughs).

Does playing a track like Trampled Underfoot cast your mind back to when you wrote it?

No, I’m always present when we’re doing that sort of stuff. Actually, I was thinking, “Don’t screw it up, and try to remember where you are, John. This is Trampled Underfoot, let’s get this right!”

Did you make any actual mistakes on the night?

Er, no! (coughs sarcastically). I can hear the odd mistake go by but if you worry about making mistakes you’ll never take any chances and we are about those chances.

You joked about there being a next night, and there was speculation that you would carry on. It didn’t happen. How did you feel about that?

Robert plainly didn’t want to do that sort of thing any more, which was fine. We did the right thing rather than press-gang him into something that he didn’t want to do. It would have affected the music. It would have affected everything. Having worked quite that hard with Jason and Jimmy I just thought, “Let’s get another band together.” We would have had to do some Zeppelin songs because of who was in the band, but we did have a lot of new material too. We went into rehearsal and we wrote stuff in rehearsal and we started getting certain singers in. There was one singer I liked, largely because he had the range to sing Zeppelin songs although he sounded nothing like Robert. As he wasn’t a replacement for Robert it didn’t matter. He sang the new stuff really well.

Was that Myles Kennedy from Alter Bridge?

Yes, a really nice bloke too, but I don’t think Jimmy’s heart was in it. I might have press-ganged him into it, but I did feel that we should do something, anything, but it fell apart. Then, of course, Dave Grohl called me and said, “Do you want to come over and play with Josh [Homme]?” And that became Them Crooked Vultures.

So you’ve got all this post-Zeppelin material written. What are you going to do with it?

It will never be heard.

While Robert Plant struggles with the Zeppelin legacy still, Jones wears it lightly, using it as an entrée to work with other musicians but refusing to be drawn into the dramas that have engulfed the group at various stages. “Don’t ask me, I’m just the bass player,” he jokes at one point when asked whether he has ever had to act as the conduit between Jimmy Page and Robert Plant. His patience is evident when it comes to the Celebration Day release. “Somebody asked me the other day, ‘Why did it take you so long to get this live DVD out? It’s taken five years.’ I said Five years? That’s like five minutes in Zeppelin time.” For all his pragmatic qualities, Jones’s lack of time in the spotlight during his Zeppelin days is something that he often returns to during our conversation.

The legacy of Zeppelin seems to weigh lightest on you. Why is that?

I don’t know. So many things have happened… I’m happy playing music and if one thing doesn’t happen, then another thing will. I’ve said before that I only had two ambitions: one was to never have a proper job and the other was to spend my time playing music all day if possible, and I’ve managed both. As long as I’m playing and making music, I don’t care.

So how do you view Zeppelin’s legacy?

I’m hugely proud of Zeppelin, you know, and I won’t have anybody say anything against it because I know what we were and I know what we did. We did great work and we influenced a lot of people, a lot of musicians and music generally. We introduced people to music that they never knew about or wouldn’t have listened to through things like the acoustic set [played on the 1970, ’71, ’72 and ’77 tours], which introduced folk music. Then there’s Middle Eastern music, blues and soul, it’s all in there. But it got bigger and bigger and bigger and I can’t say that I enjoyed those later concerts as much, the really big ones, because Zeppelin was much more subtle than that, and in the end all those big places are all about broad gestures. That said, it was better than it is nowadays where it’s all karaoke! (Laughs) Band turns up, audience sings.

The O2 was completely the opposite of that.

Yeah. People were back listening to music again. And, of course, the other thing that Led Zeppelin means to me is I can get good tables in restaurants.

I appreciate your honesty…

…And it bought me the freedom to do whatever I like. I can make whatever music I want to without having to worry about it.

When you look back at the O2 show, was there anything that you realised you hadn’t noticed before about the band?

I can’t say that there was except the fact that we were bloody hard workers. That, and how much we actually care about presenting the music and the show. We all put everything into it. We had our finger on everything. All of us did.

I worried about seeing the film...

(Interrupting) What if the show wasn’t as good as you remembered it? We felt the same way. Robert and I went to see a bit of it because we were talking about it. When we saw a bit of it we went, “Bloody hell! That’s really good isn’t it?” That’s when we went round to Jimmy’s and said, “You’ve really got to see this.” Jimmy saw it and said, “It’s good, let’s put it out.” But getting any decisions in this band is really difficult. I don’t know why, but it’s always been that way. Then again, there was no point in cobbling something together and sticking it out. It had to be up to the standard that we’re all happy with, and it is. I’m really pleased with it. Plus I got some light on me this time!

It’s funny you should mention not getting enough of spotlight – this morning Robert was worried about getting too much of it. He also said that he found it hard to fit in musically because of the musicality in the group.

I do appreciate that he is in a difficult-ish position because there are times when it’s just instrumental. What does he actually do when it’s just instrumental? He never had a problem before because he used to prance around, and occasionally he would join in with vocalising. But there are times when he’s not singing at all and sometimes it’s for an extended section. So I can understand that but to put it in those terms, that he doesn’t fit in musically, I don’t know what he’s thinking sometimes because he’s every bit as integral as any of us. That’s the whole thing about the band. It was four members all the time.

So, bearing in mind Robert’s reservations, do you think will Zeppelin ever play again?

I doubt it. I seriously doubt it. I’ve always said never say never but I can’t imagine it. (Pause) I shouldn’t think so. I must admit that I don’t think I’d like to tour like we did all over again.

Presumably it wouldn’t work like that. It would be a handful of dates…

We’d have to do quite a large tour. You couldn’t do just a couple of shows because of the amount it would cost you. And then everybody would want you. The other thing about those big tours is that you can’t do anything else at all and I’ve got an opera to do.

From a personal point of view, what did the O2 represent?

I think it reminded everybody what we were. Obviously, it’s not what we were because there’s no Bonzo there, but it’s bloody close to what we did. The way he [Dick Carruthers] has filmed it means that you can see the inner workings. It’s pretty authentic in terms of how we used to operate and I hope they get an insight into what it was like. And I’m glad that they get to see the rhythm section with some light on them after all this time!

I’m glad that hurt hasn’t stayed with you.

I don’t know what you’re talking about…(laughs)

Jimmy Page: "Things can be achieved even under impossible odds."

Jimmy Page opens the door to his hotel suite looking tanned after a two-week holiday in Thailand from which he has just returned. “I needed a bit of a break after working to get this thing done,” he puffs, referring to his hands-on approach to Celebration Day, the second film project he’s been involved with in the space of four years following on from 2008’s It Might Get Loud – Davis Guggenheim’s love letter to the art of guitar playing in which Page starred alongside The Edge and Jack White.

As Led Zeppelin’s leader and producer, Page has always taken meticulous care over every project that bears the band’s name. “Things have to be right, otherwise why do them at all?” he says when discussing the lengthy process that has led to the release of Led Zeppelin’s O2 show.

For Page, the band’s reunion show was also marred by the injury to his finger. “Fuck! That wasn’t much fun!” he winces when reminded of the episode. “But even a broken leg or a broken finger wasn’t going to get in the way of that gig. If I’d broken my leg I would have sat down and played the show! I don’t want to tempt fate, though,” he says with his customary sense of reserve coupled with justifiable pride. It is these two qualities – wariness and an overriding desire to explain the detail – that animate his conversation, and today there is a fair bit of detail to talk through.

In 2010 you told me that you didn’t think the O2 show was going to come out. What changed?

Yeah, well, I wasn’t sure at first about putting it out but the fact was that the show was bootlegged within hours. There was somebody from Japan who recorded it and who had it out in, it was said, 36 hours, although that may be an exaggeration. Including the flight [back to Japan], I can’t see how that could happen but that’s how quick bootleggers were to respond to it. When I saw the rough cut of it which I believe was from the in-house mix, it was pretty exciting but that was pretty much what was already out there on bootleg so I wasn’t sure about what to do. Basically, we had to improve upon that so that it would satisfy all areas, really. If it is even the last bit of Led Zeppelin live product or whatever, just as we had to go there and stand up and be counted on that night, we had to make sure that we were able to do the same thing with the film, and that took a while. I think we got there and it’s certainly got its moments, hasn’t it?

It has. People appear to have forgotten that it would have been easy for you to have fallen flat on your arses at that show…

You’re right. You only need a trainwreck in the first number and then another one two numbers later and you’ve got a disaster on your hands.

So when did you feel comfortable on-stage?

It wasn’t that I felt comfortable, but I felt it was going well pretty quickly. It was also this feeling of wom-wom-wom (makes surfing movement with hand) movement.

It was pretty intense even before we went on-stage to be honest. I was getting nervous, getting pumped up way before I went on. It was just this adrenaline that was really going. “Let’s get on there. We know we’ve put a lot of time and a lot of planning into the set so let’s see if we can get on there and go Bang! Bang! Bang! with those first numbers.” I think people were shocked that we’d put so much effort into it because they could tell straight away and there was this sense of ‘What’s coming next?!’ But we had to put everything into it because we only had that one shot. There wasn’t a warm-up gig. That was, that was… unique because no one does that. Everyone who does this kind of thing has a warm-up, we didn’t. We had a production rehearsal [at Shepperton] four days before. Then we had a soundcheck at the gig. But in the run up to we’d put a lot of work into it over the weeks. It wasn’t every day of every week but we were really were investing our time and our passion and our dedication into what we were doing.

The first song was Good Times Bad Times – a song you’ve never played in its entirety. Why start with that?

Because it’s the first track on the first album. First track, side one…

Were the opening lines to the song significant?

Yes. Well, you could think that and it would be really pertinent to think that because there is

a narrative there. But there was also the intensity of taking it on as the opening number which simply said: They’re not messing about.

The second song you played was Ramble On from Led Zeppelin III – another song you hadn’t really played live. Why?

Well, it wasn’t like we were going to do the first track of the first album and the second track off the second. It was more of a case of us thinking that after the whole attack of Good Times Bad Times we should take it down to this sort of lyrical guitar playing of the introduction, although I’m not sure people even recognised it until Robert started singing it! But it was a total contrast to the first number and taking us through there were the power choruses of that song which took us on to Black Dog – which people are fully aware of. It was a case of, “Take that and there’s more coming!”

For Your Life was the fifth song in the set. Robert said that despite the fact that he recorded that track while in a wheelchair, he was in better shape than everyone else. Is that song a symbol of a turbulent time?

As far as the Presence album? Yeah, but regardless of what anyone thinks, what’s important? It’s the music, not the myth that goes around it. The music is what’s important. The whole of that album was done in three weeks, and that’s it.

Anyway, For Your Life is a pretty complex song when you listen to it and it’s one that we’d done in the rehearsals [leading up to the O2] which was almost like a challenge. It was a case of, “Let’s see if we can do this” We were playing the record to just reconnect. We thought, “If we can pull it off and put that in most people will probably never know what it was, apart from people who really love Led Zeppelin.” And, sure enough, there were a few reviews that said, “They did a new song!” They were obviously referring to For Your Life. The song came just at the right time. Before that we did In My Time Of Dying, for heaven’s sake! That’s not messing around either!

It isn’t. So how did you arrive at the final set?

OK. You don’t end with Stairway, that’s for sure but you certainly should end with Kashmir or at least have that towards the end of the set. As I said, we’d worked out the first three and then the set started to shape itself.

The improvisational element in Zep has always been close to your heart. How much room did you leave for that?

Well, for the first three numbers the only room for manoeuvre was in the guitar solos. On that first solo I wanted to keep it fairly close to the original of Good Times Bad Times, but by the time it gets to In My Time Of Dying, I’m taking chances there which I’m sure people will see when they see the rehearsal on the DVD edition.

Basically, we’ve included the production rehearsal as a second disc. This is really radical stuff because who would actually do that? We took a chance doing one show, so we’ll take a chance of also giving people the rehearsal so that you get two different shades of the band.

The rehearsal is a one-camera thing so you can’t muck about with it and it doesn’t have the dynamics of the live show, but you can see how the music moves and it has a lot of relevance in that sense. There’s a noticeable difference between our approach and you can see the back screen coming into play as the production elements come in. I think the production rehearsal also shows how ready we were to do the O2, but it presents an intimate view of how we work and it makes a statement about that.

The intimacy of the live show is also evident on the DVD. It is like almost watching you in a rehearsal room because even if there are 18,000 people there you get this real sense of the performance almost from within…

Yeah. You get the sense that everyone is listening to each other and we’re attentive. It gets into another sort of zone, really.

I remember the sound being a bit muddy for the first three songs. Did you have to clean it up?

Actually, it’s interesting because on-stage we were almost playing blind – or deaf – because of the monitoring. But we were rehearsed and we knew what we were doing, then it started to shape up and there was more clarity on stage. When I went to see the rough cut the sound of the night, yeah, it was a bit muddy but it was still pretty exciting so it was a question of giving it more clarity but still giving it that emphasis of the power. And I must say that Alan Moulder, who did the mix on it, was brilliant.

Did you overdub anything on it?

No, there were a few fixes to do but I didn’t do any guitar overdubbing. Maybe I should have done, but it is what it is. There are a few things that don’t work, but there is a lot that does and, unless something is really howlingly wrong, then we haven’t replaced it. It wasn’t overtly sexed up, if you see what I mean. Or under-sexed or castrated in a way! Sexed down, in that respect.

Back to the set, Robert said that on the night there were “thousands of emotions” running through you all, playing, say, Kashmir…

(Interrupting)…You could feel that! You could really feel that! It really was quite something. It was really powerful on-stage.

So, when you were playing Kashmir, what was going through your mind?

If it’s evocative musically, it’s not just a series of pictures going on it’s an emotional thing for me.

I can’t say anything more because that’s how it is. It’s a damn fine piece of music, Kashmir. To be part of playing that on-stage and to know that it’s really got it’s intent and it’s moving is overwhelming because it’s quite a majestic piece. On the night it was really elevating, it was buoyant. Robert was flying on vocals and Jason was playing some amazing stuff. Suddenly, the whole thing really took on another dimension. Not that it hadn’t either on other numbers, but for Kashmir it was all-important that it went like

that and it just did, you know. The spirit was there! (laughs)

When you played Rock And Roll, the final song of the set, you didn’t know if there’d be any more shows at that stage. What did you feel emotionally? Thank God, we’ve got it done?

No. It’s quite clear from everyone’s expressions at the end that it had been a personal triumph for all of us. Collectively, too, it was a triumph that we took this on and that we pulled it off big time. In retrospect, if we’d been in the Boston Garden or the Marquee, at that point we would have carried on playing for quite a long time, probably doing requests, because why would we want to stop?

The following day, because I’d paced myself towards an evening performance, I started to get a bit fidgety and I would certainly have enjoyed a second show. I’d like to think that we all would have done because it would have been interesting to see the differences that would have gone on the following night, even if I don’t think that we would have adjusted the set.

But that was the thing that we didn’t know. At these warm-up gigs you see whether the set works. We didn’t have that. So for all the planning of it, and the various moods of the songs and the intensity of certain songs in relation to others, we didn’t know whether it would work until we got up there and played the set to an audience. That was what was so great.

Despite the fact that the band split in 1980, you get the sense that Jimmy Page never left Led Zeppelin. Rather, the death of John Bonham forced the band to leave him. Like Plant and Jones, Page has subsequently struggled to find another vehicle that can match the sheer scale and power of the band he founded in the summer of 1968. His renewed alliance with Plant in the ’90s came close, the Unledded project yielding fine reinterpretations of key Zeppelin tunes, but the following studio album of all new material, Walking Into Clarksdale, failed to hit the anticipated creative heights. Since then, Plant has run in the opposite direction from Zeppelin while Jones has played for fun. Page, however, has no problem admitting his love for his former group, viewing its entire experience as a sensual adventure where experiences fuelled the music and vice versa. “Playing in Led Zeppelin was a musician’s dream,” he says. Now, however, Page appears to have reconciled himself to the fact that the dream is over.

“Right now, five years ago, we would have been rehearsing for the show,” he says, casting his mind back and opening up on his decision to release Celebration Day. “I could see the time ticking by and there hasn’t been a hint of us doing anything again so, while we can still be in control of this, we should do it and present it properly because that’s probably going to be it.”

You do realise that releasing Celebration Day means you are going to be asked when are you going to play together again, don’t you?

Yes, and my answer to that will be very simple. And very truthful. That, coming up to five years – it will be five years in December. (Speaking emphatically and slowly) That. Is. A Long. Time. The gig, as you can see, was really infectious. We were enjoying it for all the right reasons. But there hasn’t been a whisper since then about doing anything and so I can’t really see that anything will happen. If it was going to happen, it would have happened by now.

I was talking to Robert today and he said he felt he struggled to fit in in Led Zeppelin – he saw himself as a singer in a band of musicians…

It’s unfortunate he thinks that way, but the testament of Led Zeppelin material just disproves that theory altogether.

During the course of today I’ve realised that it’s about the different ways in which you all approach the Led Zeppelin legacy...

Yeah, but, hold on a second, the legacy would weigh down upon us but to focus on that one thing that was the O2, as far as I’m concerned, we could shed any demons or whatever because we proved just how good we could be. If that’s the last testament of what we did, then that’s fine. That’s really good. I’m really glad that we’ve done it and that you’ve actually seen it and other people are going to get a chance to see it. I’m happier that it’s out than not out. Absolutely.

So can you understand why Robert didn’t want to continue playing shows with Led Zeppelin after the O2?

Yes, I can understand why he might. It’s his decision, after all. And now it’s five years on so I can’t imagine anything is going to trigger a change in him. To be honest, it’s been five years and we’ve moved on. I think, back then, there were other things that he wanted to do so he did them. He wasn’t keen to do Zeppelin so we had to respect that. That said, his decision not to do more shows wasn’t based on the strength of that one show because I think we all agree that we really played well.

“To be playing Kashmir on stage and to know that it’s really got its intent and it’s moving, is overwhelming.”

Jimmy Page

And you were keen to carry on…

Well, if Jason, John Paul Jones and I were playing afterwards then, sure, we were willing to go beyond the element of the O2. But we couldn’t do anything that was a Led Zeppelin reunion unless the singer was there. Quite clearly we’re there, but he’s not so what’s the point of playing games with it?

Equally, you could do Zep numbers with you guys in the band, even with another singer…

Hey, listen, if I was going out on my own I’d do Led Zeppelin material, but I’d do Yardbirds too. But if we had come up with some kind of concoction with the three remaining members, we wouldn’t call it Led Zeppelin would we? We would play new material but of course we would do material from the past, not least of all because I enjoy playing it and I can probably play Led Zeppelin guitar better than most! (Laughs) I’ve had a good schooling it in. People love that music and I would play it because I’d have fun doing it. Without having fun there’s no point doing it. You wouldn’t go through the motions would you? Well, I wouldn’t. To be honest, I’d rather go and play with a samba school.

Speaking of music away from Zeppelin, you’ve been releasing material through your website.

Yes, there’s been a couple of soundtracks which I released on vinyl via the website [jimmypage.com], Death Wish [II] and Lucifer Rising, but there are more releases to come too. There’s quite a bit of stuff from my personal archive that I’d like to get out there, but then the O2 project came into the picture and that really has been a massive thing to do and it had to be right. There are also a number of Led Zeppelin projects that will come out next year because there are different versions of tracks that we have that can be added to the albums so there will be box sets of material that will come out, starting next year. There will be one box set per album with extra music that will surface. But, really, the plan, as I’ve said before, is to make new music.

When will that be?

If you’d asked me a year ago I would have said that I wanted to be working by this time this year, and then all this stuff went on. The masterplan is to get it out late next year. The instrumental side is almost done and, while it’s too early to really talk about it, I’ve started on the preparation of how to present it. I think there will be vocals to be introduced but at the moment I am obviously concentrating on the stuff we have to do around the O2 release because it’s been all-consuming.

Final question: for you personally, what did the O2 show represent?

What did it represent? (Pauses) That things can be achieved even under impossible odds. And I’m glad we did that.

In October 9 Jimmy Page, Robert Plant and John Paul Jones are in New York City attending the US launch of Celebration Day at Museum Of Modern Art, after the UK press conference of two weeks earlier – the latter not the most satisfying experience for band or the audience.

“I think it went…OK,” says Page, hesitating. “But there was a point where I wondered whether we were at a coconut shy… with us as the three coconuts on-stage.”

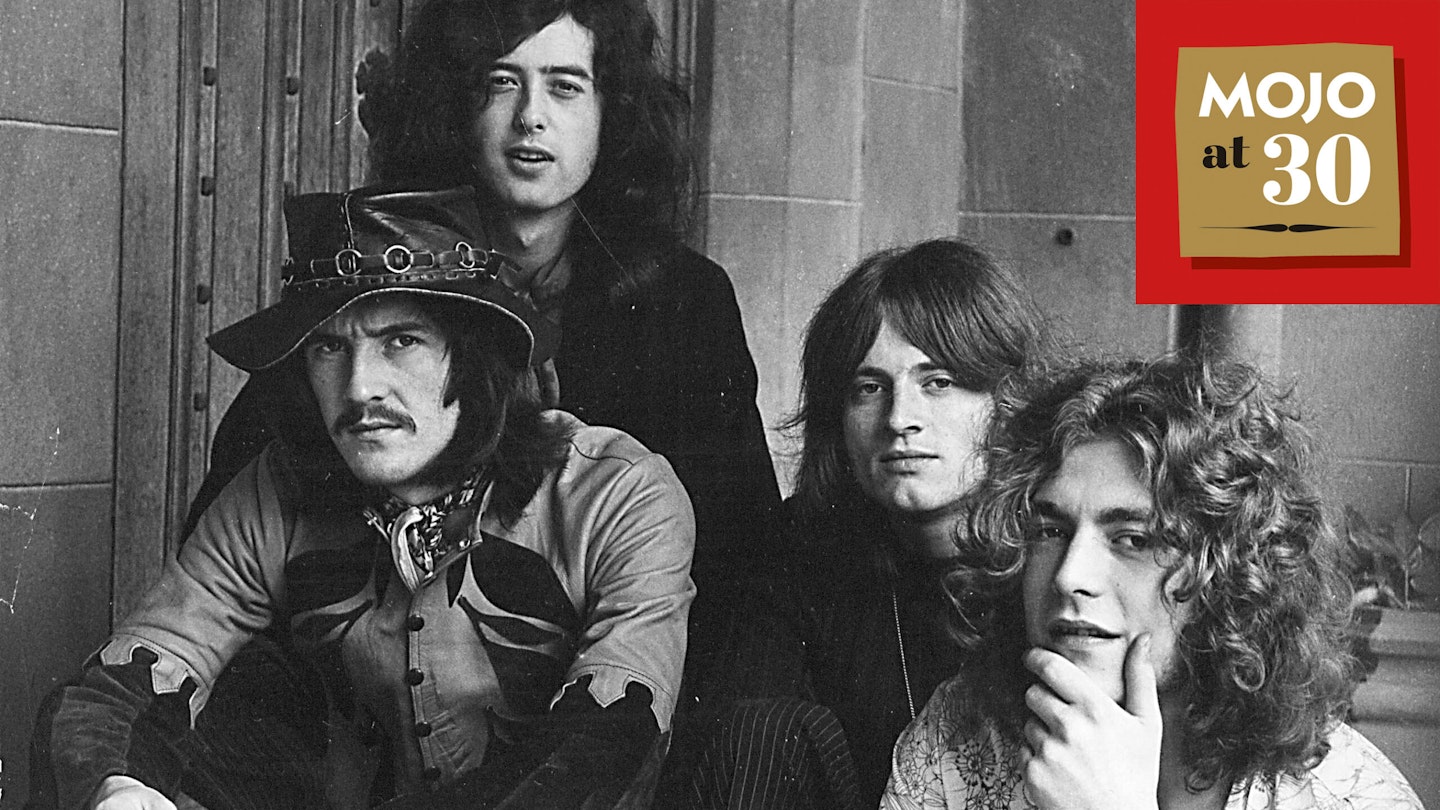

During their time in New York the trio also take time to undertake a photo session for MOJO with photographer Ross Halfin on the roof of the Riverton Hotel. The mood in the Zeppelin camp seems to have thawed considerably since the three sat down individually to conduct their interviews – a point reflected in the shots.

A further screening of Celebration Day at Hammersmith Odeon, London, on October 12 follows and is attended by band members and their families. Again, a sense of camaraderie seems to surface. Whether this rapprochement is significant is unclear. Page, Plant and Jones are due to reunite again on December 2 when they attend annual Kennedy Centre Honours at the Kennedy Centre Opera House, Washington DC. So, will Led Zeppelin be allowed one last hurrah beyond that? Right now, only three people know the answer.

This article originally appeared in MOJO 229.