In 1990, World Party’s Goodbye Jumbo heralded a restoration of ’60s pop values and promised the big time for its eccentric auteur, Karl Wallinger. But the obsessiveness that made a masterpiece could have cost him his life, and a “horribly clandestine” flit by his band didn’t help. In 2021, MOJO wondered whether we could detect new, faint strains of genius at work? “It’s useless to try and find out what I’m up to,” he warned James McNair. In memory of Wallinger, who has passed away aged 66, MOJO revisits the interview in full…

“Pay, you will pay tomorrow”, warned World Party’s debut single Ship Of Fools. Its soulful, perfect pop was a Trojan Horse for a stark environmental message, and in April 1987, it was the minor US hit no-one saw coming. Industry suitors were quick to react, though, and high-tailed it to Bedfordshire, England. It was there, in a dilapidated rectory, that Karl Wallinger had made World Party’s Private Revolution almost single-handedly, pseudonymously crediting his guitars to “Rufus Dove”, and his harp-playing to “Martin Finnucane”, a character in Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman.

“They’d heard there was a dumb kid in Woburn writing hits,” says Wallinger today. “There was this beauty-parade of visiting managers.” Among them was Steve Fargnoli, then already employed by another, rather more famous multi-instrumentalist. “I was a sucker for Prince”, says Wallinger. “I was like, ‘Take me to Minneapolis. Take me to your leader…’”

Wallinger had already witnessed The Purple One’s genius first-hand. In December 1984, he was still playing keyboards in The Waterboys when they opened for U2 on The Unforgettable Fire Tour. In Chicago the support act “nabbed Bono’s limo”, sidestepped U2’s set, and went to see Prince instead.

“It was incredible, but having listened to Purple Rain smashed one night me and Mike [Scott; Waterboys frontman] had already concluded that Prince was the Messiah. You know: I Would Die 4 U and all that…”

Better yet, with Fargnoli now his manager, Wallinger could touch the hem of Prince’s garment. He recalls a New Year’s Eve dinner at Paisley Park with Prince and Miles Davis jamming inches from his food. And a Mercedes ride across Paris to the Bois Du Boulogne apartment that was once home to Edward and Mrs Simpson – and was at that time rented by Prince.

Prince disappeared into the bedroom in a brown polka-dot number and came out in a blue polka-dot number. Meanwhile, I was playing the piano very drunk.

Karl Wallinger

“He disappeared into the bedroom in a brown polka-dot number and came out in a blue polka-dot number. There was a beautiful young Moroccan woman with him and he romanced her by the window. Meanwhile, I was playing the piano very drunk and ended up falling on the floor.

“Like most mere mortals, I was a little in awe of him,” Wallinger concludes, smiling. “I think the only thing Prince assimilated from me was those little hexagonal glasses he wore on the cover of Sign O’ The Times.”

READ MORE: Prince interviewed: “I am a giver by nature. I like people, but I test people in many ways.”

June 16, 2021. Wallinger is talking to MOJO in his garden in Hastings, house martins darting behind him. “Pandemic?” he says. “My life hasn’t changed. I’ve been out three times in 15 months, and one of those was to the chiropodist.”

Together with sculptor wife Susie Zamit, the singer moved to the town he’s dubbed ‘Nashville-on-Sea’ some four years ago. “I put the bird-feeders out, then get into my music head,” he smiles.

As Wallinger moves indoors, MOJO spies the inner sanctum of Seaview Studios, named for earlier incarnations in Woburn, then Islington, but this time actually affording an ocean vista. As he skins up and MOJO mentions the new World Party LP Wallinger hopes to release early in 2022, there’s a playful caveat: “It’s useless to try and find out what I’m up to.” Wallinger also reveals that nobody else - not even his family - has heard the new material he’s been writing.

Even before the February 2001 brain aneurysm that almost ended him in a Center Parcs resort in Suffolk, Wallinger was a ruminant creator, forever chewing the cud. Five years of rehabilitation slowed him further as he painstakingly re-learned guitar and piano. Then, eventually, after acclaimed World Party live shows in 2007 and 2011, came 2012’s Arkeology, a typically eclectic and playful 5-CD clear-out of his ever-congested sock drawer.

It’s been 21 years, though, since World Party’s last new studio album Dumbing Up; 31 years since his masterpiece, Goodbye Jumbo. And though Wallinger has recently busied himself re-releasing his back catalogue on vinyl through his own label, you sense he’d sooner keep pottering than stick his head above the parapet.

“In World Party I thought I was writing songs for the next Live Aid, a kind of global unity thing,” he told this writer in 2000. “When I was young, the music of The Beatles and Motown and Sly [Stone] was such a unifying force, so I was singing about unity and about how, for me, the natural world is one of the few real truths, whereas human society is a fuck-up.”

A torch-carrier for the ’60s pop canon, Wallinger, like his Liverpool contemporaries The La’s and US counterparts Jellyfish, sought that special sauce that made The Fabs fab. The ’80s were not for him (“Spandau Ballet? Foghorn plus racket”), and Britpop and The Beatles’ Anthology were still half a decade in the future. “I was just trying to return to a musical place I liked,” he claimed. But World Party’s green message was prescient and heartfelt, a fervent post-script to ’80s consumerism.

“I still don’t think about much except music and current affairs”, says Wallinger today. “Meanwhile pop music has a whole different set of rules. I hear it, but I don’t get it, really.” He scratches at close-cropped grey hair, pulls on his spliff. “I guess I’m hoping that a 63-year-old Welshman can say something relevant, post-apocalypse. Who knows how close it is to a parting shot?”

Growing up in Prestatyn, Wales, Karl Edmond De Vere Wallinger spent many Sunday mornings dancing to Buddy Holly and Motown 45s with his elder sisters. He gained a more formal musical education in choir school at Eton – “Think Tom Brown’s Schooldays, with these awful, elitist people throwing pennies at us out the window” – and then at Charterhouse in Surrey, where he’d won a scholarship to study piano and oboe.

Having moved to London for a job at ATV Music Publishing in 1981, Wallinger also worked as musical director of The Rocky Horror Show and covered Shalamar and Sly & The Family Stone in short-lived band The Out before joining The Waterboys in 1983.

He contributed organ, piano and b.v.s to 1984’s A Pagan Place, but Waterboys leader Mike Scott promoted him somewhat on 1985’s This Is The Sea, for which Wallinger received a co-production credit, co-wrote Don’t Bang The Drum, and helped shape The Whole Of The Moon’s distinctive sonics.

“We definitely had some great times, and there’s still a part of me that thinks it would have been interesting to continue,” says Wallinger. “It was my first experience of record releases and going on big tours, but it wasn’t like I was going to take a lead vocal and by album six I’d be doing six tracks and replacing Mike, you know?”

“Karl was always there for me,” Mike Scott tells MOJO today. “He was a great engineer, got great sounds, [and] was very patient while I would play nine different guitars. Reefers may have been involved, and some all-nights. We had a lot of laughs and philosophical discussions.”

Was Wallinger’s departure inevitable?

“From the day I met him he was always writing his own songs, so yes. The label I was with, Ensign, gave him a record deal and he deserved it, of course, but it wasn’t the smartest move if they’d wanted to keep him in The Waterboys.”

READ MORE: "Bob Dylan heard The Whole Of The Moon and he liked it..." Mike Scott interviewed

In 1989, Private Revolution’s Ship Of Fools was a shoo-in for Greenpeace’s Rainbow Warriors compilation. It was World Party’s 1990 follow-up Goodbye Jumbo, though, which really chimed with green-leaning listeners. Its Eden-like vision of environmental stewardship and mutual tolerance was notably feel-good, as UK Top Ten single Message In The Box underlined.

“I wanted to personify the world and sing about her”, Wallinger told me in 2000, when I asked about his vision circa Jumbo. “I always thought it would have been great if Otis Redding’s Try A Little Tenderness had been about the planet. Plus, if I stand on top of a mountain Julie Andrews-style, the hills do seem to be alive with the sound of music. You can say whatever you like about eco whatever, but if you fuck up the environment you’re going to die.”

By now he had moved his Seaview operation to Islington, London, renting “a grotty old paint shop that made effects pedal boards for people like Steve Howe.” There, with “Abbey Road aspirations”, and with help from Joe Blaney, engineer on Prince’s Lovesexy at Paisley Park – “his settings for vocals are still crayoned on my mixing desk” - Wallinger was able to craft an eclectic landmark with beatboxes and slide guitar, Lennon-like piano ballads, uptempo party-funk and languorous, falsetto-driven soul.

Better yet, World Party was now a ‘proper’ band, its members including former Icicle Works and La’s man Chris Sharrock (more recently drummer in Liam Gallagher’s Beady Eye and in Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds), and, more crucially, keyboardist Guy Chambers, future writer-producer to the stars. “It was fun to have a band”, says Wallinger. “We came back from the pub one night and did a version of Good Vibrations. It’s still unfinished, but still.”

“The sessions for Jumbo were during the night”, says Chambers today. “So we’d get there about 5pm, have breakfast, then work until dawn. We smoked copious amounts of dope all through the night, every night.”

Even at the time, Chambers found Wallinger’s a challenging regime. “If you worked with Karl you had to get into his headspace. Everything was very slow and you had to be extremely patient. I was one of Karl’s principal cheerleaders at that point. We laughed a lot and I learned a lot from him, particularly about lyrics, but he was a terrible procrastinator and still is now.”

Wallinger concedes that, from start to finish, Goodbye Jumbo took “two or three years”. All the same, he knew it was something special. “I basically just enjoyed making music in a way that would never be so easy again,” he says. “All my stress dissipated to neutral, and I had this January where I slept like a baby.”

The 1990 Q Magazine Awards saw Goodbye Jumbo win Album Of The Year. Wallinger melted when Paul McCartney approached his table and said, “Show Me To The Top! That’s the hit on that album!”

“It was like getting a letter from Santa”, he says. “Just the fact that Macca had heard my stuff meant so much.”

The near-unanimous acclaim for Jumbo should have been a powerful springboard, but gremlins meddled. A live broadcast of album closer Thank You World from the Kilburn National on Channel 4’s Live From The Dome was potentially Wallinger’s All You Need Is Love moment, but a catastrophic mix meant viewers heard little more than Guy Chambers’ backing vocals. Wallinger was devastated: “I watched thirty seconds on video at home then got into a warm bath and slit my wrists.”

But the more lasting damage, he says, came from Ensign’s insistence that he begin work on Jumbo’s follow-up immediately: “Nowadays you would tour the fuck out of the Q Award thing, but [late Ensign Chief] Nigel Grainge was like, ‘No, you can’t go and support Neil Young in America – get back in the studio,” and for me that meant three more years out of sight.”

Still, 1993’s Bang! arrived with a useful tailwind, and with David Catlin-Birch, sometime bassist for The Bootleg Beatles, now on board, it charted at Number 2 in the UK on the back of breezy single Is It Like Today, described by Wallinger as “a précis of Bertrand Russell’s A History Of Western Philosophy in four verses.”

The Bang! era also had other consolations, not least a chance meeting with Sir George Martin at Air studios in Hampstead.

“I was there in 1994 doing music for the film Reality Bites”, recalls Wallinger. “Me and Chris Sharrock came in late one morning and George happened to be standing in the foyer. He said, ‘What time do you call this? I’ve already done two tracks with Elton John.’ It was so lovely to be told off by him. We went giggling up the stairs like naughty schoolboys thinking, ‘So that’s what it was like to be a Beatle!’”

It wasn’t Wallinger’s first encounter with Martin. Three or four years previously, sitting at the keyboard in Martin’s office at Chrysalis Records, the Beatles producer had given the singer a one-to-one masterclass on melody and harmony, Wallinger taking notes and not letting on that he had his own version of Strawberry Fields Forever on a cassette in his pocket. The impact of this summit was considerable. Having canoed down the Nile of Beatles veneration for years, Wallinger had reached its source.

“I came out of there like Billy Bunter leaving a sweet shop”, he says. “You have to remember that George was the steroids that made The Beatles go ‘Boom!’”

It was Guy Chambers, Wallinger said in 2000, who was “the pushy guy who would cue me into the corner pocket” circa Goodbye Jumbo. “I’ve got to thank him for that.”

But their relationship soured when, having bowed out on 1997’s Egyptology, World Party’s final major label release, Chambers recorded its Wallinger-penned piano ballad She’s The One with Robbie Williams, using World Party’s rhythm section, without Wallinger’s knowledge. Williams’s near-facsimile reached Number 1 in the UK in November 1999 and subsequently won a Brit Award for Single of The Year.

“Thank God they did record it”, says Wallinger today. “It kept me and the family in spaghetti when I was ill and couldn’t work. But at the time it seemed horribly clandestine and then Robbie stole my band and I was like, ‘What are you doing, guys?’ I’m obviously a cunt.”

“The only person we took was Chris Sharrock”, argues Chambers in partial mitigation. “So just the drummer. I did try to take Dave Catlin-Birch, but he didn’t want to leave. Rob [Williams] was so obviously heading towards stadiums and Chris saw which way the wind was blowing. You couldn’t blame him – it was better money.”

Chambers also says that “Karl’s been a bit tricky with She’s The One.” As its writer, he has exercised his right to block video of Williams performing the song, “and for years he wouldn’t acknowledge how useful [our version] has been for him. Karl’s version is great, of course. It’s the original. But when we recorded it I said to him, ‘This version’s a demo - let’s do it properly.’ Because, like so much of the World Party stuff, it was thrown together in the night. When I did it with Rob we put pop strings on it. If you want to make a hit record, sometimes putting out a demo isn’t the best thing…”

Williams’ version of She’s The One would become ubiquitous at weddings and funerals. Meanwhile, Wallinger’s major label career was ending, albeit at his own request. In 1998, frustrated by “a whole different regime that didn’t seem to know anything about music,” he extricated himself from EMI.

“I was originally signed to Ensign, then went through Chrysalis and Polygram before EMI bought up the whole world. I didn’t want to do another album for a joke-nose-and-glasses brigade, so I said ‘Just give me my back catalogue and I’ll walk.’”

Then in February 2001, just as World Party were gearing up for live dates that April, Wallinger’s brain aneurysm struck. The years of apparently endless studio prevarication, spent chainsmoking obsessively, appeared to have caught up with him.

“I had a very unhealthy lifestyle and doctors will tell you everybody who smokes deserves to die horribly,” he reflected, “but I think it had more to do with me playing oboe in my youth. There’s a lot of pressure build-up with woodwind…”

Wallinger says he never felt like he was going to die, “although I could have done. I expected to feel a bit dodgy after they’d sawed my head in half, but what pissed me off most was waking up with a catheter in. Christmas shopping was fun, too. I had no peripheral vision and people thought I was bumping into them deliberately.”

And today? Has the aneurysm changed his outlook on life?

“Well I save more donkeys than ever - let’s put it like that.”

Were peak-period World Party a band out of time? A truer, more sophisticated keeper of The Fabs’ Flame before Britpop, Oasis, and the sundry Beatles-ness that Guy Chambers and other producers have since sprinkled like fairy dust? Typically, Wallinger’s take is not so straightforward.

“I definitely think we were feeding that multicore and expanding it,” he says, “but it’s a strange one, World Party. Not recommended for you sanity. We never really got there”, he adds, exhaling spliff smoke and grinning. “Fate’s not letting me travel as the crow flies.”

So where does he fit in as a songwriter, as a musician? One of the Great British Eccentrics?

“That’s probably more accurate than I care to think”, he muses. “Karl Wallinger’s music - has it fucked his mind? But music is the greatest thing for me, because it takes me somewhere that it’s safe to be. Ultimately, I’m just a guy who makes noises in a room and plays them to as few people as possible (laughs). But I’m happy and I’ll be back after these messages…”

This article originally appeared in MOJO 337.

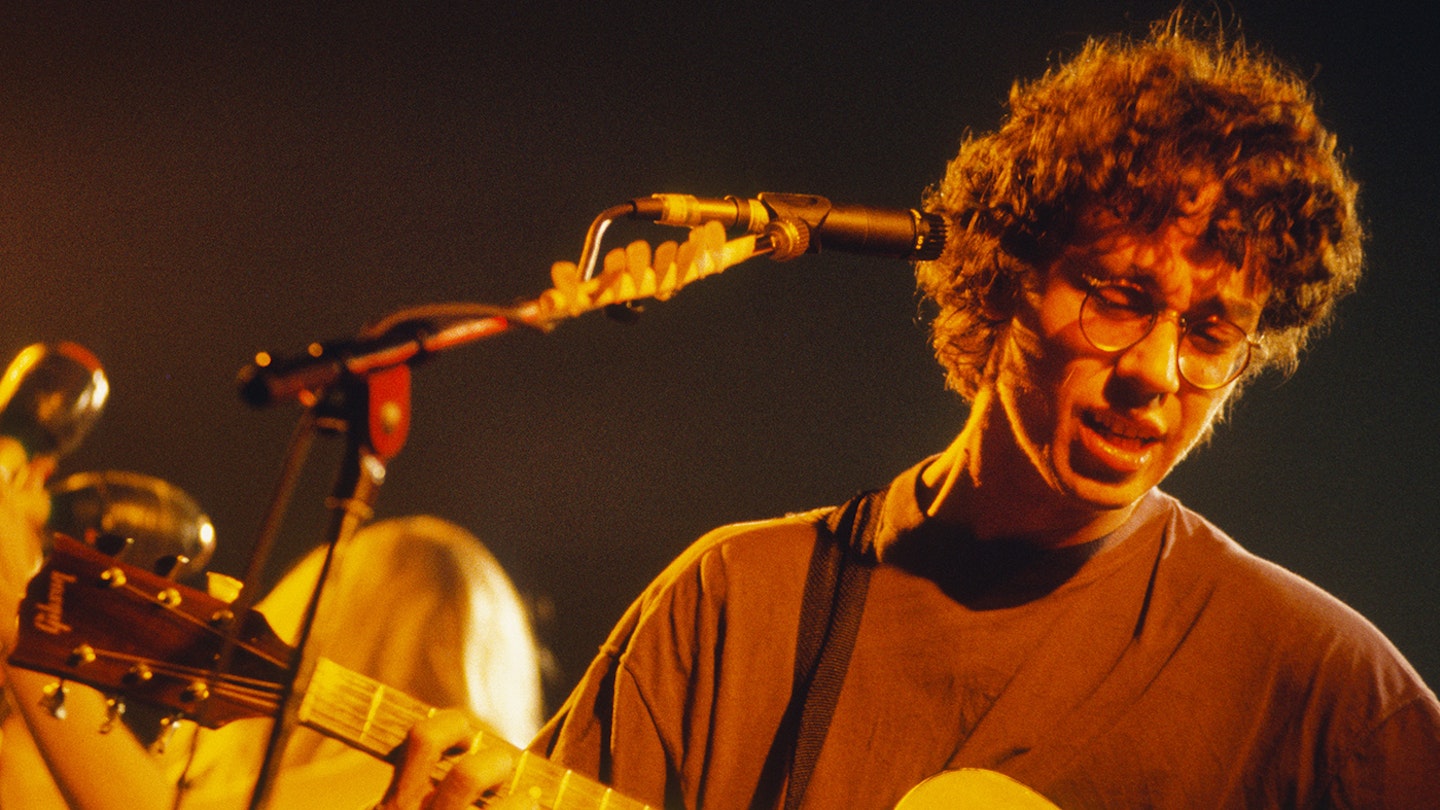

Picture: Gie Knaeps/Getty