Released on this day in 1989, The Stone Roses’ self-titled debut album injected the free-spirited attitude of the previous year’s acid house movement into a set of chiming, 60’s influenced songs of freedom and optimism. Striking a chord with indie kids and terrace scallies alike, the album paved the way for Britpop acts to come the following decade, most notably Oasis, whose frontman Liam Gallaghercites seeing the group perform as the moment he realised he wanted to be in a band. Here, the album’s producer John Leckie speaks to MOJO about getting the call to record a group from Manchester who would soon prove to be exactly what the world was waiting for, and why he walked away from the sessions for their much delayed follow up, Second Coming.

“BEFORE THE ROSES, I’d produced The Woodentops, The La’s, and XTC as The Dukes Of Stratosphear… To be honest, my motivation was, The Woodentops hadn’t made it yet, nor The La’s, so it better be the Roses! [Rough Trade boss] Geoff Travis had sent me their original demos, but by the time I replied, they’d signed to Zomba. Ian Brown mentioned the Dukes’ album? One thing I didn’t realise for years is that Made Of Stone’s vocal melody is the same as the Dukes’ 25 O’Clock, I think Ian nicked it. Maybe that’s why they chose me, but I think it was because Geoff suggested me.

My first impression of the demos was, “Oh, another indie band.” It was badly recorded, everything was too fast and the vocals were over-drenched in reverb. I knew it would be a challenge. I had to rehearse them and rearrange songs, giving them intros and outros, and steady tempos. For I Am The Resurrection, they wanted to jam the second half, all feedback and noise like they did on-stage. I said, ‘That’s boring on record; do something melodic that people will remember.’

John [Squire] could be critical, less making suggestions and more, ‘Why can’t that bit sound as good as that bit?’ He wanted to explore different amps and guitars, but he made most of the first album with a Stratocaster, a Fender Twin Reverb amp and JBL speakers. He was always quiet, and when he did speak, it was usually profound. He’d set up his 16-track Fostex recorder in a little space in the studio, or his bedroom at Rockfield, and spend days in there, working out parts.

Mani was always great. I don’t remember difficulties recording Ian. Reni was a fantastic drummer, and a great harmoniser, but he wanted to sing on everything! Ian would say, “Can we turn Reni down?” Ian thought the harmonies sounded too ’60s.

I get so engrossed in recording that I never project in terms of an audience or the impact a record will make; you just want to make something that you’d listen to at home. We always knew I Wanna Be Adored would start and I Am The Resurrection would end it, but once we had the whole running order we realised, ‘Fuck, that’s good.’ Of course, John and Ian hated the record. They said the drums and bass weren’t loud enough, and the guitar needed to be more devastating: they’d been playing Public Enemy in the studio all the time, full blast.

After the album became successful, Zomba said, “Do whatever you want.” Ian and John had the Fools Gold demo with the breakbeat loop from [James Brown's] Funky Drummer and we spent three weeks at Sawmills in Cornwall recording it and What The World Is Waiting For. It took four days alone just doing the wah-wah guitar. There was no Pro Tools then to do it for you, but limitations made you try harder.

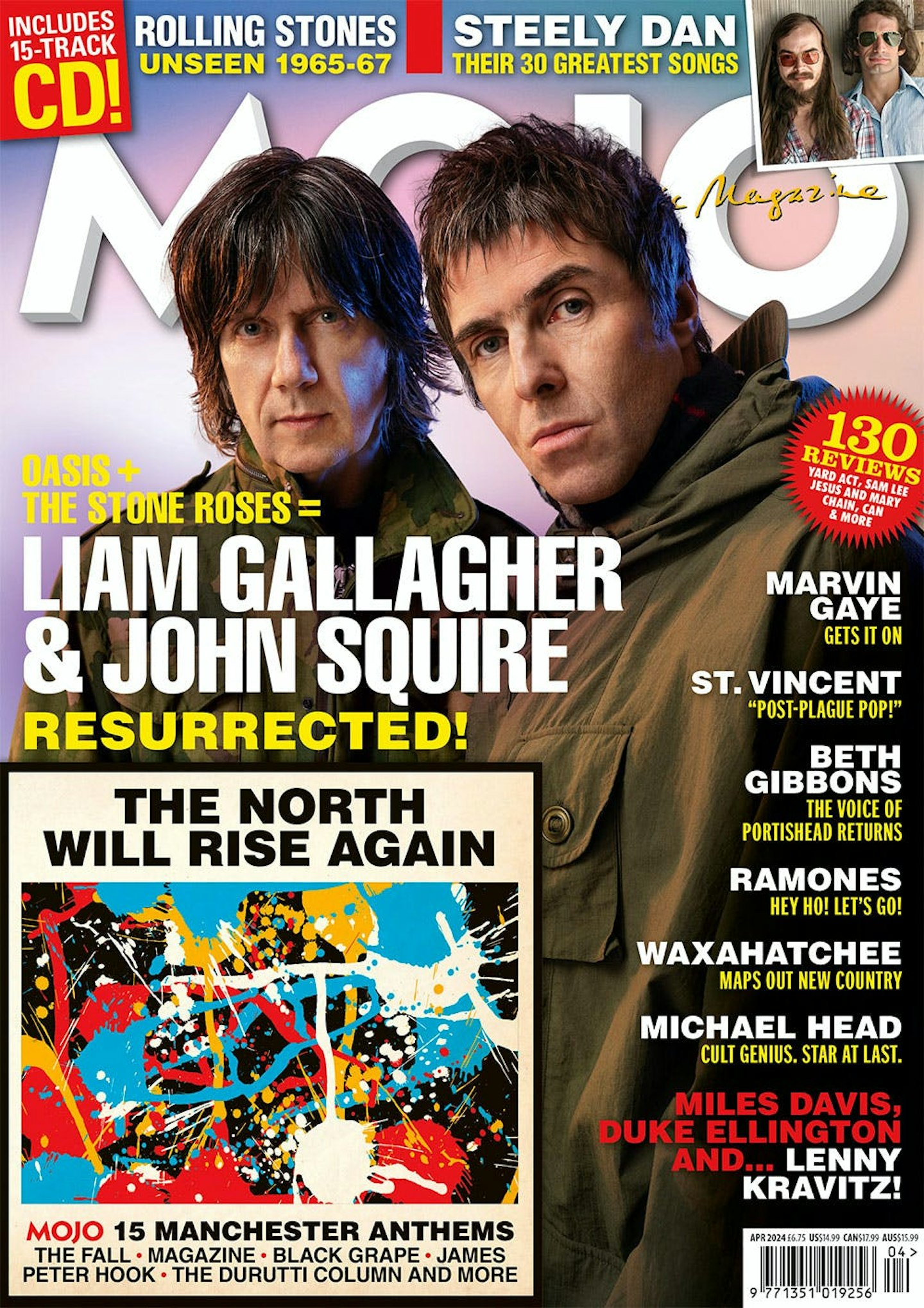

Thirty-five years on, my grandchildren listen to The Stone Roses. Not because of me, but their friends at school. ‘That record with the funny colour and splashes of paint, you did that didn’t you? Got any vinyl, any T-shirts?’

I knew the second album was a problem when they didn’t show up. Reni would go home for days, or John wouldn’t come out of his room. Or they’d endlessly play the same thing over and over. There was no A&R man around, no manager by then, it was just me and them. I told [A&R] Gary Gersh, ‘We’ve been here three weeks, and they’ve done nothing...’

He said, ‘No problem, just let them be creative, don’t worry about the budget.’ The studio cost £800 a day – and the programmer hired to do loops for £400 a day was just sitting there. They had the best drummer in the world, and they wanted to use drum machines! It was a nightmare. I left after three months and they finished Second Coming 14 months later.

When I worked with him, John was a great writer, a good arranger and between a good and a great guitarist. He was still ‘indie’; not like he is now, playing stadiums. By the second record, he was into the whole Jimmy Page, Led Zeppelin thing, but he’d never been to America, and that would have made a big difference. I was always disappointed that the Roses never expanded their horizons.”

This article originally appeared in MOJO 365. More information and to order a copy HERE.