Released on this day in 1966, The Rolling Stones’ first album of purely Jagger-Richards originals established the band’s identity forever: nasty, jaded, uncaring, misogynistic… but also darkly charismatic and musically brilliant.

“Mick and Keith write about things that are happening,” The Rolling Stones’ manager Andrew Loog Oldham told Disc magazine in April 1966. “Everyday things. Their songs reflect the world around them. I think it’s better than anything they’ve done before.”

-

READ MORE: The Rolling Stones Lost, Rare And Unseen!

Oldham’s summary of the Stones’ fourth UK album hit on the fundamental element that made it such a momentous departure from its predecessors, and the equal of their best records to come. Musically, Aftermath will be remembered for its thoughtfully crafted pop songs, fleshed out with exotic instruments including sitar, dulcimer, harpsichord, marimbas and bells. But as the first long-player to consist exclusively of Jagger-Richards originals, it also gave the world the first tantalising reports of what “the world around” the group was like in the aftermath of Satisfaction topping the US charts in June 1965.

At that time, life as a Rolling Stone had become a flickering carousel of screaming fans, hotel rooms, airport lounges and interminable bus rides, the “everyday things” of an 18-month tour-of-duty in 1964 and ’65 designed to make them as big as The Beatles in Europe and America. Inevitably, perhaps, the world that Mick Jagger and Keith Richards would write about was bound to reflect road-fatigue – yet the songs on Aftermath exhibited a hard-bitten cynicism that would be alarming in musicians twice their age.

The Stones could not, it seemed, get any satisfaction anymore, however exciting their lives appeared from the outside: after the girls, the drugs, the adulation, everything now was just one big drag. Across 14 tracks, they spat out their disdain for submissive women (Under My Thumb), women they happened not to like (Stupid Girl), rich women (High And Dry), touring (Goin’ Home), hangers-on (Doncha Bother Me), travel (Flight 505) and suburban housewives (Mother’s Little Helper). Virtually every song contained a vivid flash of anger, spite, frustration, boredom, homesickness, paranoia, or any other of the dark emotions that would consume the band as the ’60s progressed.

Recording began at RCA Studios in Hollywood on December 8, 1965, two days after the group had wound up their fourth major US tour in LA. With the success of Satisfaction and Get Off Of My Cloud, the 4-track facility – with engineer Dave Hassinger at the controls – was now the group’s studio of choice. When the Stones assembled for the first session, they were tired and tetchy, the 31-date tour having taken its toll with its unrelenting see-saw of wild adulation and bitter hostility.

Legend has it that Andrew Oldham locked the group in the studio during the day, concerned they might flake out for good if they were allowed the respite of a hotel bed. Thus ensued three marathon sessions that went on from midday to long into the night. Brian Jones was reported to have played some of his guitar parts lying on his back. One day he didn’t turn up at all. It was the first real sign of the problems which would lead to his departure from the group.

-

READ MORE: Brian Jones: It was murder

During the American tour, Mick and Keith’s relationship with Brian had curdled into an uncomfortable mixture of mutual tolerance and open irritation. In Munich a few weeks before they’d left for the States, Jones – the blues and R&B purist – had once again showed his contempt for their latest pop hit by playing Popeye The Sailor Man during Satisfaction. A blazing row followed in the dressing room; Jones saw it as another attempt to undermine his confidence and what remained of his band-leader status. With Andrew Oldham encouraging Mick and Keith to write more originals together – during snatched moments in hotel rooms, on planes, on buses – Brian suddenly felt a chill wind freezing him out.

Perversely, Jones’ gradual relegation to jobbing musician and band hedonist was to bring out the best in him as a multi-instrumentalist. His acquisition of a mountain dulcimer in North Carolina, in mid-November, was to ultimately result in the resplendent, Tudor-ish backing to one of Aftermath’s greatest triumphs, Lady Jane. Dropping in and out of the sessions in December, he would rouse from his exhausted state to bring Mick and Keith’s creations to life with inspired splashes of sitar (Mother’s Little Helper) or dirty, ambient fuzz-guitar (Think).

After taping the poppy Mother’s Little Helper, the band returned to their R&B roots for the chugging Chicago blues of Doncha Bother Me and the epic Goin’ Home, an 11-minute blues monster featuring road manager Ian Stewart on piano and Charlie Watts on brushes, wigging out into a doomy, thrillingly unpredictable jam. Once the track was in the can, the group did indeed go home, via various pre-Christmas holiday destinations.

-

READ MORE: "He was the rock the rest of it was built around..." The Rolling Stones pay tribute to Charlie Watts

In January, while the group rested, Oldham announced that the new record would be called ‘Can You Walk On Water?’, only to be promptly reprimanded by an outraged Decca. He could already sense that the follow-up to Out Of Our Heads was going to secure the Stones messiah-like status, and the second batch of sessions, again at RCA in Hollywood, on March 6-9, 1966, would prove his instincts correct.

Perhaps given new spirit by his relationship with German model Anita Pallenberg, Jones came into his own as a musician, lifting a fresh batch of Jagger-Richard compositions with thoughtful dustings of organ, sitar, bells and dulcimer. (The awesome Paint It Black, which made the US version of the album, was also cut at these sessions.)

READ MORE: "If you take it too seriously you're fucked..." Keith Richards Interviewed

Perhaps his finest contribution was the lilting, baleful marimbas on Mick’s undulating temple to misogyny, Under My Thumb – a song rendered virtually perfect by Keith’s slick, jabbing guitar licks and Bill Wyman’s grooving bass pattern.

As the musical brilliance flourished (the elegant Lady Jane, the soulful Out Of Time), so the lyrical snottiness swelled. Stupid Girl described its subject – reportedly Jagger’s squeeze Chrissie Shrimpton – as the “sickest thing in this world”; High And Dry, a song about being ditched by a rich girl, smart-assed “lucky that I didn’t have any love towards her”; the booming Think begins, “I’m giving you a piece of my mind…”

Pop music had rarely sounded so mean and nasty; indeed, The Beatles’ elevated, avant-garde Revolver, released a few months later, seemed like music for intellectuals and old people in comparison.On its release in April 1966, Aftermath climbed to Number 1 in the UK and 2 in the US. It had captured an astonishing burst of creativity. More importantly, it cemented Mick and Keith’s reputation as stellar songsmiths who could now stand toe-to-toe with anyone.

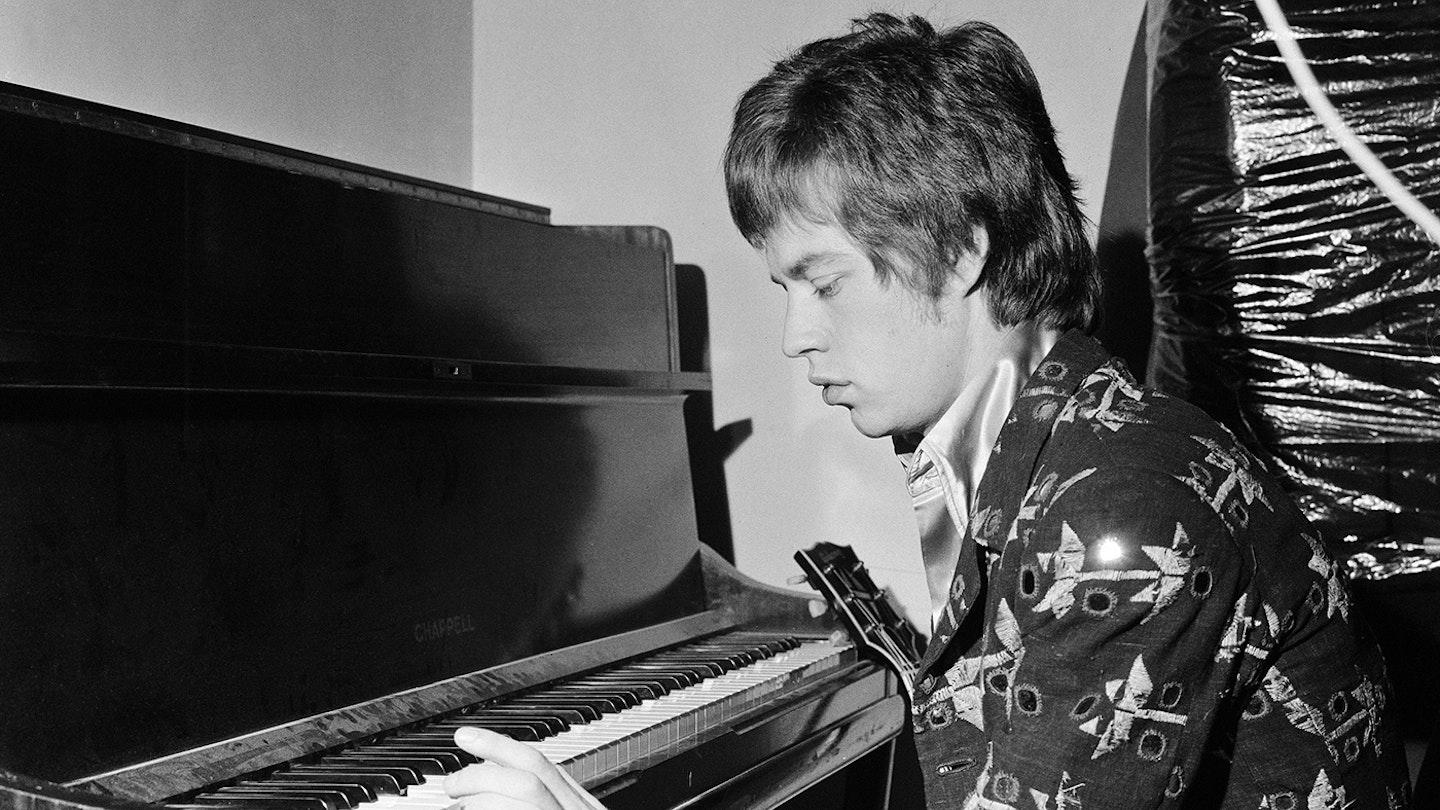

Photo: Alamy