In 1993, aged only 35, Paul Weller was already regarded as something of an elder statesman in the UK music scene, even written off as yesterday’s man in some corners of the press. Yet, drawing inspiration from the green spaces of his childhood in Woking, he began work on a second solo LP that would redefine him as an artist. On the anniversary of Wild Wood’s release, Weller, producer Brendan Lynch and The Blow Monkey’s Dr Robert, who played on the album, speak to MOJO’s Tom Doyle about the making of his first solo masterpiece…

In the early ’90s, after more than a decade spent living in London, Paul Weller began returning to his native Woking, drawn to many of his childhood and teenage haunts in the surrounding Surrey countryside.

“I don’t know what drove me to do that,” he reflects today, sipping a coffee and puffing on a fag at a table outside a Maida Vale café. “I just reconnected with a lot of places around there. I realised how long it’d been since I’d thought about those days. I’d been on this fucking mad journey and gone totally somewhere else.”

-

READ MORE: Every Paul Weller Album Ranked!

Weller had only turned 35 in the spring of 1993, but he was already regarded as something of an elder statesman of rock, or even written off by some as yesterday’s man. “I felt old because I’d already done so much,” he reasons. “I’d gone through that whole experience with The Jam, and then The Style Council. And then nothing. And then I was almost starting again and trying to build this thing back up and find my mojo, y’know. Get it back on track, man. Enjoy writing again. Enjoy playing again.”

It was a process that had begun with his self-titled 1992 solo debut, with its blend of modishly looped-groove rock songs (Into Tomorrow) and trippy, soulful ballads (Above The Clouds). Wandering back through the green spaces of his past, he found bucolic inspiration for what was to become his landmark second solo album, Wild Wood.

“There was kind of an Englishness and a folkiness about some of Paul’s writing at that time,” says his friend since the ’80s, The Blow Monkeys’ singer Robert Howard – aka Dr. Robert – who remembers Weller giving him a copy of Donovan’s 1967 double album, A Gift From A Flower To A Garden. “The acoustics came out again and we would play those songs together, like Wear Your Love Like Heaven, and analyse them a little bit. I think that was the beginning of what turned out to be Wild Wood, for him.”

One particular field just outside the Surrey village of Ripley – with “a view to this copse, quite far away,” as Weller details – provided the lyrical impetus for Shadow Of The Sun, a song which found its writer looking back at his boyhood dreaming, taking stock and determining to “have it all while I’m still young.” It was a track demoed, like many of the others, at the nearby Black Barn Studios, a facility Weller ended up buying in the late ’90s, which he still uses as his recording base today.

“I was only thinking of this in recent months actually,” he says. “I was looking at it and thinking, ‘That’s that same field I wrote that tune about.’ Now it sort of makes sense because that’s where the studio is. Whether that was a sign, I don’t know.”

“Sometimes, after years of going through all the music business machinations,” reasons Dr. Robert, who ended up contributing guitar to Wild Wood, “you need to reconnect with the child inside you, and what it was that was first kind of lit. I think there was a lot of that in what Paul was doing. He was feeling energetic and ambitious again.”

Back in 1993, by looking to music’s past and connecting the threads to music’s present (an approach to which MOJO magazine also committed upon its launch), Weller discovered a future for himself, with the folky shades and fiery rock of Wild Wood as its blueprint.

“It’s quite an inspired record,” he states. “There was an excitement going on. It felt like it was building up and going somewhere.”

It was like a fucking wonderland...

Paul Weller

Wild Wood was in fact recorded in a different rural location, 64 miles northwest of Ripley and Black Barn, at The Manor in the Oxfordshire village of Shipton-on-Cherwell. The fabled residential studio, owned by Richard Branson and inhabited down the years by such disparate characters as Sandy Denny, Gong, Tangerine Dream, PiL and XTC, was housed in a Grade II Listed 16th century country pile set within sprawling gardens. Its laidback, pastoral atmosphere was to lend itself to the beatific vibe of the record.

“It was the first time we’d been there,” Weller says, “and it was just like a fucking wonderland or something. There was a room in the house where the grand piano was, and we had a [drum] kit and some little amps in there. So, even after the sessions, we’d go on and have a jam.”

“We’d be in the dining room, or we’d go on the lawn,” remembers Dr. Robert. “Wherever we were, there’d be guitars about, and people would be playing. So it was that pure music vibe. It was a totally immersive experience. You’re not going home… you’re not breaking the spell.”

Elsewhere, in The Manor’s living-cum-listening room, records were spun, and cassette mixtapes played into the wee small hours, shaping the contours of the album. Traffic are often cited as the chief source of inspiration for Wild Wood. “Definitely an influence,” Weller nods, “but I mean people were probably saying that because it had a flute on it!

“From the ‘90s onwards, I was listening to so much different music which I’d cut myself off from in the past. I was sort of blinkered when I was younger. To the point of not buying records because someone had long hair or a beard. I dropped any sort of barriers at all and so it was a real learning curve as well.”

Other names on the Wild Wood sessions playlists included CSNY, Nick Drake, Free, Donald Byrd, Shuggie Otis and A Tribe Called Quest, whose Luck Of Lucien from their 1990 debut _People’s Instinctive Travels And The Path_s Of Rhythm led Weller, via their sample usage, back to jazz-funk trumpeter Billy Brooks’ 1974 album Windows Of The Mind.

“They were sampling music that was made in the early ’70s,” reflects Wild Wood co-producer Brendan Lynch. “We were trying to get the same feeling.”

If The Beatles had been a Weller staple since his childhood, their chief influence on Wild Wood was in his guitar choices, mirroring those used on Revolver: John Lennon’s Epiphone Casino, George Harrison’s Gibson SG, Paul McCartney’s Höfner bass.

“The Casino was used on Sunflower,” Lynch recalls. “As soon as Paul played that intro guitar and the drums came in, it just immediately sounded amazing to me in the studio. Once we got that, we really knew we were onto something. Basically, what I heard in the studio when they were playing was the record.”

Weller and his band – the core of which comprised time-served Style Council drummer Steve White, Young Disciples bassist Marco Nelson and flute/horn player Jacko Peake – were audibly on cracking form. “Paul wanted [the album] to be upfront,” says Lynch. “Folky, acoustic, but powerful… really in your face. It was great to see him creatively hitting a new high.”

In its Black Barn demo form, the title track of Wild Wood, which Weller had envisaged as a “modern-day folk song”, was more electric guitar- and beats-driven. At The Manor, it was stripped down into its final form as a slow-burning acoustic ballad.

“It wasn’t really working for us,” Weller says of the original, “and it might have been Brendan’s idea to simplify the whole thing.”

“It really worked out,” says Lynch. “We tried recording outside first of all, with Paul in the yard at the studio. We had a couple of umbrellas over him to try and stop the wind. It sounded good, but it was unusable because of the elements. So, then it was, ‘Let’s put him inside,’ and we got it in a few takes.”

On Wild Wood, there was an assurance to the performances that was sometimes at odds with the doubt and questioning apparent in the songs’ lyrics. Lynch recalls one day when Weller picked up a magazine in the studio and read a blisteringly dismissive piece about himself.

“Basically it was one of those articles: ‘Paul Weller, where did it all go wrong?’” the producer recalls. “He put it down and he went, ‘That was a bit harsh.’ That’s all he said. But quite soon after that, he’d written Has My Fire Really Gone Out? I thought that was kind of an answer to that… those naysayers who thought he was finished.”

“It was me just taking the piss really,” Weller says now. “Because I was written off, especially from the late Style Council onwards. And on that first album, there were some shocking reviews. Y’know, saying, ‘He’s over… he’s finished.’ It was like, ‘Really? We’ll fucking see about that.’ That always puts the fight in me, which is a good thing.”

One other standout track was raw and personal in a different way. All The Pictures On The Wall was a vivid depiction of the ennui and sadness of a romantic breakup. “I was not happy in my marriage [to singer and Style Council member Dee C. Lee], and I felt it was breaking down,” says Weller. “I thought we’d lost whatever it was.”

However, thinks Weller, he may not have been aware of the song’s full implications. “’Cos I remember playing it to Dee, on the guitar. Just saying, ‘Oh, I’ve got this new tune.’ And she was really sad. On reflection, I suppose it is personal because our marriage broke down a couple of years after that. Some of these things become more apparent with time.”

Lullaby-like album closer Moon On Your Pyjamas was meanwhile a song of fatherly devotion written for the couple’s then-five-year-old son, Natt. “I was away on Natty’s fifth birthday,” Weller recalls. “I was on tour in America somewhere and I was really gutted, and I remember writing that song for him. But I’ve never asked him what he thought about it. Not for years anyway.”

Taken altogether, these very adult themes only served to enhance the appeal of Wild Wood for Weller’s returning, and expanding, fan base. Many of those who had followed the singer through The Jam and The Style Council were now likely going through similar experiences or challenges. Upon its release, the album went straight into the UK chart at Number 2.

“I think there’s a lot of themes on there that probably people did connect with,” he says, “’cos we were all in the same boat really. We were doing this parenting and couples thing and just trying to make it up as we go along, as you do.

“One couple said to me, ‘Oh, you helped us get our love life back together. We listened to that album, and we reconnected.’ I thought, ‘Ah, good. Quite a lot of information, but good.’”

As an addendum to Wild Wood, Weller and the band returned to The Manor in January ’94 to record a standalone single: the beautiful, aching Hung Up. A Number 11 hit in April, it was his biggest solo single up to this point and immediately tacked onto the track list for the album’s re-pressings.

“I think it was me realising that you’ve just got to drop some of your hang-ups and move on from them,” Weller says of the song. Capturing the dreamy-headed mood of the times, the success of Hung Up was aided by its striking video featuring the ensemble – now joined by Weller’s soon-to-be trusty sidekick, Ocean Colour Scene guitarist Steve Cradock – looking ’66 Beatles cool while performing on the lawn at The Manor.

“We were all on Es, man,” Weller laughs. “It was in them days. Fucking Es and whizz. Not Whitey, but me and Cradock definitely.”

Another new high was reached in June ’94, when Weller and the group appeared on the Pyramid Stage at Glastonbury, powerfully upstaging headliner Elvis Costello. “We smashed it,” he grins. “He came into the dressing room and said, ‘Don’t give us too much of a hard time tonight, will you?’ And we were like, ‘Nah… don’t worry about that.’ But we won that day, definitely.

“A mate of ours, he’d just come up on his acid, and we started playing Wild Wood. He said he could see these beams of sun behind the stage, like God’s fingers. (laughs) It was fucking mega.”

Three decades on, Weller recognises that Wild Wood was a transformational record for him. “It restored a bit of faith in what I could do really, as a writer,” he concludes. “But it’s funny, isn’t it? When everyone just seems to connect with something… You can’t plan it. You don’t even know why it’s happened. It’s just happening.”

This article originally appeared in MOJO 360.

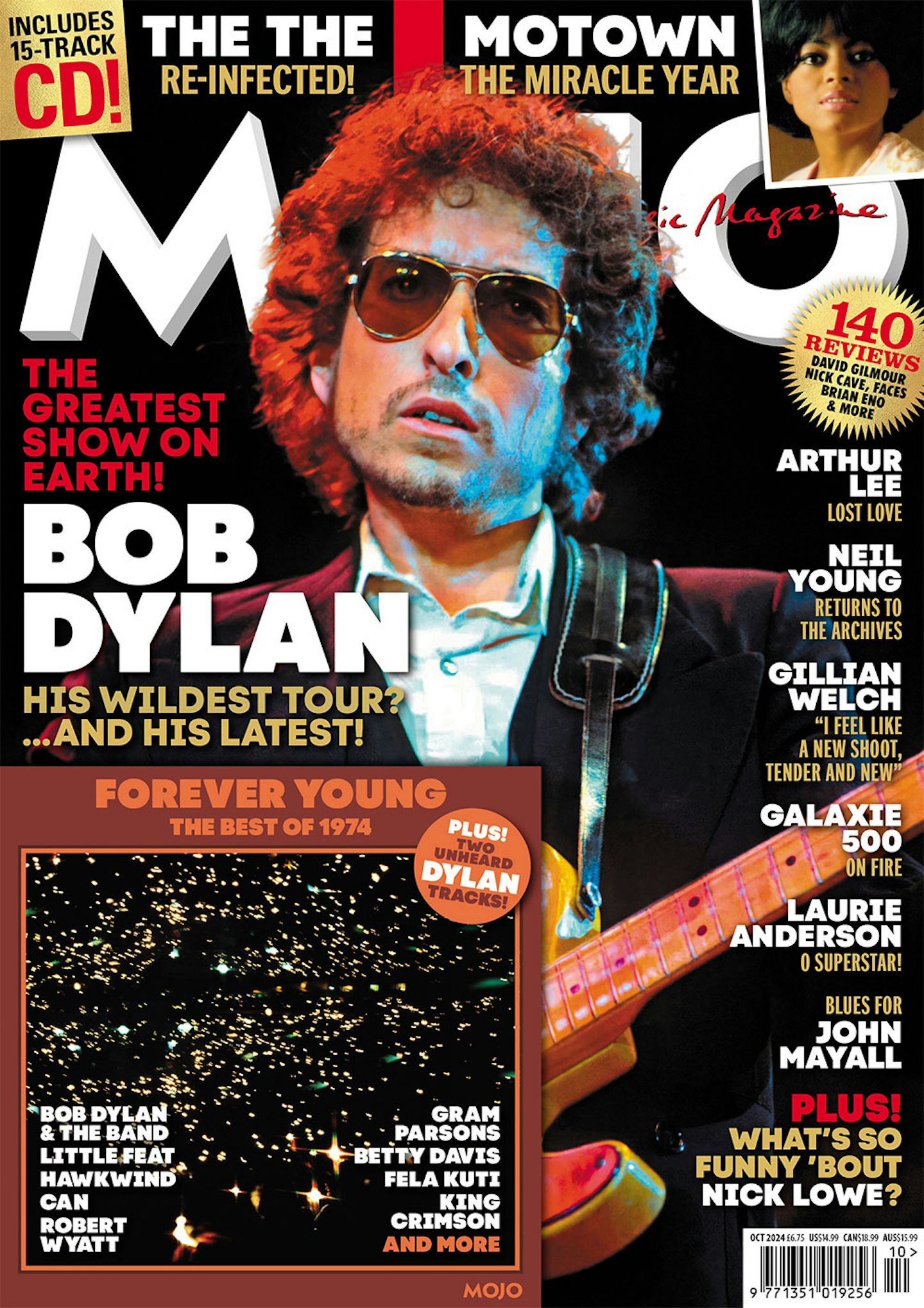

The latest issue of MOJO is on sale now! Featuring Bob Dylan, Motown, The The, Neil Young, Arthur Lee, Nick Lowe, Gillian Welch, Galaxie 500, Laurie Anderson, John Mayall and more. More info and to order a copy HERE!