Today, Kate Bush is a revered figure of the choicest sort. With Elton John, Peter Gabriel, Elizabeth Fraser, Stevie Nicks, John Lydon and more among her heavy admirers, she could, you suspect, summon music’s highest and best to the studio at a moment’s notice and they’d be fighting each other to get in. Certainly, few would show disrespect, or dare to ridicule her.

-

READ MORE: Kate Bush's 50 Greatest Songs Ranked!

It wasn’t always the case. It’s curious to reflect on how much her first few years were greeted with irreverence and even mockery. In July 1978, she appeared on Kenny Everett’s TV show, answering interview questions in the wrong order. The same year there were irreverent knock-offs of Wuthering Heights: a budget cover by the Top Of The Poppers (sung, rumour has it, by a can-do session man on the clock singing falsetto), a ‘drink-up-thy-zoider’ yokel reggae version by Jah Wurzel, aka Morgan Fisher from Mott The Hoople, and a full-on arm-waving parody by TV impressionist Faith Brown. It didn’t let up: in November 1980 ‘alternative-comedy’ TV ensemble Not The Nine O’Clock News went in hard with England, My Leotard, an acrid lampoon of Them Heavy People with future celeb sexologist and Mrs Billy Connelly Pamela Stephenson pastiching every “kooky” Bush move she could (we won’t mention comedians Little and Large’s cover of Babooshka).

Inevitably, Kate showed herself to be the consummate good sport, calling Brown’s wind-up “incredible” and adding, “I think she’s a genius.” In 1986, she duetted with Not The Nine O’Clock alumnus Rowan Atkinson on an anti-romance ditty called Do Bears… for the Comic Relief charity. Then, as now, she seemed above it all.

Of course, it seems unlikely that anyone too concerned with other people’s opinions could have made The Kick Inside. The fortuitous story of how her first album came into being - the precocious talent born to create in a home full of music, the patronage of Dave Gilmour, its extended gestation punctuated with dance lessons with Lindsay Kemp and Arlene Phillips, and playing rock’n’roll covers in the capital’s pubs with The KT Bush Band - still seems somehow unreal. Through it all she had, it seems, a clarity of intent that rendered her immune to outside influences and distractions, and remained preternaturally attuned to her own creative visions.

Recorded in AIR studios above Oxford Circus in central London, work on her first long-player began when she was still in her teens, with two tracks – The Man With The Child In His Eyes and The Saxophone Song - dating from June 1975 sessions when Bush was just 16 and yet to do her A-levels. The rest were recorded in summer 1977 with a band featuring members of Pilot, Cockney Rebel and The Alan Parsons Project, whose multi-instrumentalist arranger Andrew Powell would produce. Though Kate wanted to use The KT Bush Band, the assembled players gelled quickly: cutting three songs on the first day, performances were taped fast and live.

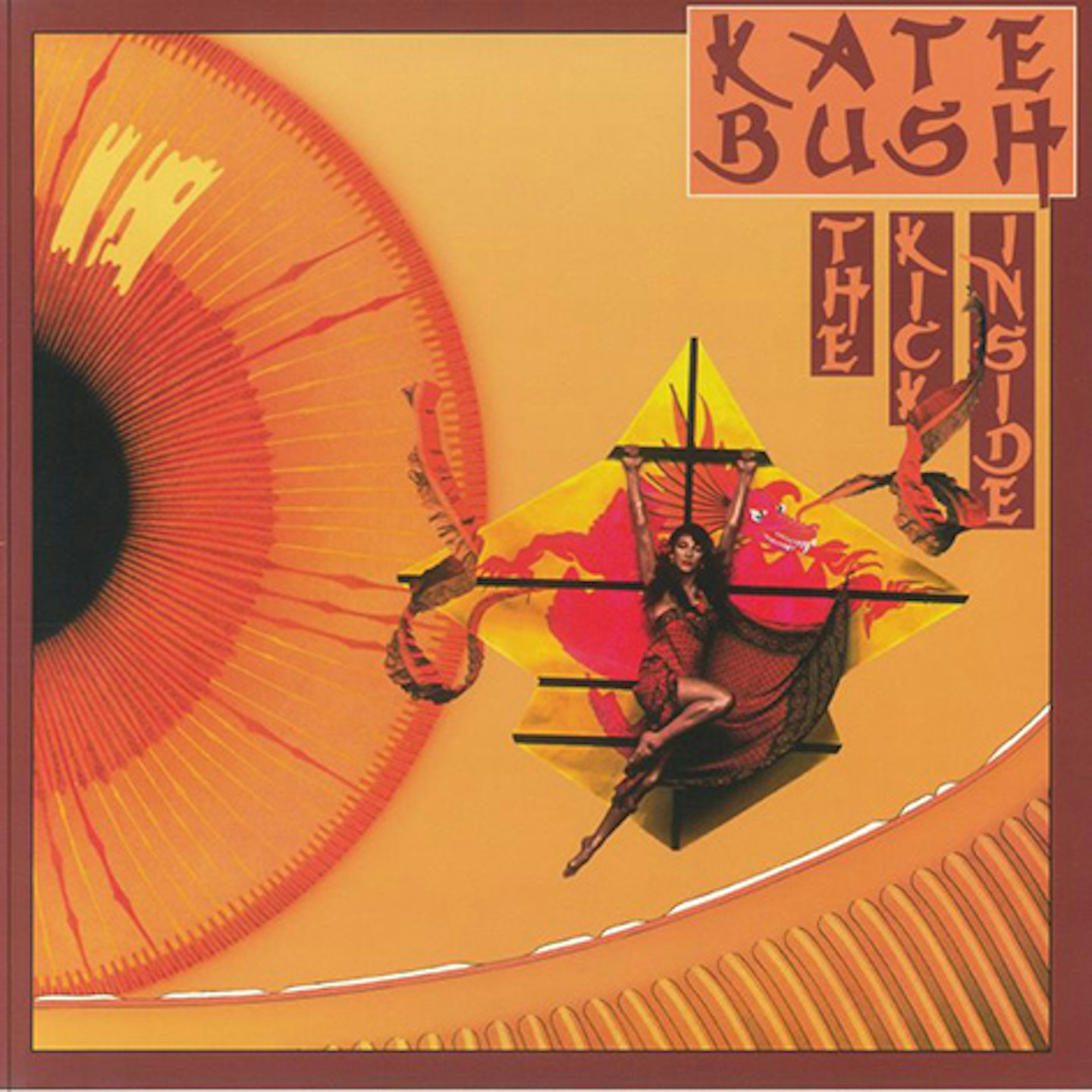

Released on February 17 when Wuthering Heights was at UK Number 27 – the single began its month at Number 1 on March 11 – The Kick Inside came clad in a chinoiserie-influenced design featuring Kate attached to a kite, covered in gold body paint. The sky she flies in is an enormous eye, an image apparently inspired by a scene in the 1940 animated film Pinocchio of Jiminy Cricket beside waking giant whale Monstro (there are another five international variants). Striking though this image is, the real flight begins when the record starts.

Guided by that extraordinary voice, in all its eldritch frequencies and modulations, a dream landscape rich in symbolism and feeling is revealed. The first sound heard is whale song, sampled from the 1970 The Song Of the Humpback Whale, recorded by pioneering bio-acoustician Roger Payne (excerpts were also included on the Voyager space probes’ Golden Records, both of which are now in interstellar space). Alien yet somehow familiar, they lead us into Moving. A rising, falling theatrical rock tribute to Lindsay Kemp – who didn’t know his pupil was a singer until she put a copy of the album under his door – it finds her soprano voice reaching out like lighthouse beams through the mist. Balletic and expressive, the suspicion that its lyrics could also be interpreted sexually are not assuaged by The Saxophone Song. Progressive pop with gutsy sax by British jazz ace Alan Skidmore, it’s earthy stuff, as she ladles on a fantasia of juxtaposed images that elude concrete interpretation: “It’s in me/And you know it’s for real/Tuning in on your saxophone… the stars that climb from her bowels/Those stars make towers on vowels”, before the static frenzy of the outro.

A vivid internal world made external, this is music which presents female experience and feeling to an intense degree (this writer was harshly informed by one female fan that not inhabiting the same biological reality as a woman means a man’s understanding of Bush’s oeuvre will remain incomplete). A feathery, hovering prog-pop question mark, Strange Phenomena contemplates menstruation, déjà vu, synchronicity, intuition and unconscious communications, and was portrayed by the singer dressed as a magician in a TV special filmed at the Efteling theme park in the Netherlands in May 1978.

The male gets a look-in on the next song, but the message is ambivalent. A Number 6 hit in July ’78, the orchestral, exquisite The Man With The Child In His Eyes was, it’s claimed, written for early boyfriend and future TV presenter Steve Blacknell, who was then working cleaning toilets at a Kent mental hospital. On that year’s US interview promo the Kate Bush Radio Special, she described the song as, “a theory that I had had for a while that I just observed in most of the men that I know: the fact that they just are little boys inside and how wonderful it is that they manage to retain this magic.”

Before offence can be taken by the liberated sensitive man of 2024 – does she actually mean me? - the ground zero of Wuthering Heights stops time, again. Sung in a morphing, trilling voice that straddles the world of the living and the dead, it’s quixotic, brilliant and utterly mesmeric. Surprisingly, it didn’t come from obsessive readings of Emily Bronte’s 1847 gothic romance, but was written in one night after watching a 1967 BBC TV adaption starring Ian McShane and Angela Scoular – later the wife of British screen cad Leslie Phillips – who died in 2011 after drinking drain cleaner. And this is just Side 1.

Side 2 continues its sophisto-rock explorations via a unique artistic sensibility, with reflections on firearms and masculinity (James And The Cold Gun), sex and intoxicating romance (a non-prurient triple-punch of Feel It, Oh To Be In Love and L’Amour Looks Something Like You), spiritual enlightenment (Them Heavy People) and childbirth (Room For The Life). The closing title song’s voice, piano and strings arrangement is lulling and sweet, but death and madness lurk at its heart. Adapted from Lizie Wan, an old British song collected by folklorist Francis James Child, with added references to the Olympian gods, it concerns a sister killing herself after becoming pregnant with her brother’s child. Few other singers could pull off this sleight of hand, of lightness and something genuinely unsettling, so convincingly.

An infamous review by Sandy Robertson in Sounds railed against “doom-laden, ‘meaningful’ songs… some of the worst lyrics ever… the most irritatingly yelping voice since Robert Plant.” Robertson later admitted just how wrong he was, but it was clear few record buyers agreed with his initial verdict. By March The Kick Inside was at Number 3, and would return to the Top 10 in summer, when work on its follow-up Lionheart was underway. When the laughter stopped, Kate Bush endured. And in 1978, this woman had much more work to do.