For all its raw power and apparent simplicity, Definitely Maybe was a hellishly tricky album for Oasis to nail. Attempting to recapture the abrasiveness and energy of the band’s 1993 demos – the fuzzy wonder of Rock’n’Roll Star, the Stones-go-baggy Columbia, the sneery, T.Rex-cribbing Cigarettes & Alcohol – was to result in three attempts to realise on tape what was set to become a landmark debut album.

The problem was that Oasis’s sound was utterly feral and (rightly) resisted being tamed. After signing to Creation Records in October ’93, the band entered Monnow Valley Studio in Monmouthshire, Wales, in January 1994 for sessions with producer David Batchelor. Noel Gallagher had met Batchelor during his days as a roadie for the Inspiral Carpets and believed that the seasoned soundman – who in the 1970s had overseen key albums by The Sensational Alex Harvey Band, including 1974’s The Impossible Dream and ’76’s SAHB Stories – was the right man to translate the band’s energetic performances to record.

Noel was to be proved wrong. In the studio, the band hammered through the songs, but then were utterly deflated when Batchelor called them through to the control room to listen to the results. Bonehead remembered the tracks sounding “thin… weak… too clean”. “He broke all the sound down… the guitar over there, the bass over there,” Creation boss Alan McGee later bemoaned. “It cost us £45,000.”

Only one track was to survive from this first, failed endeavour: the heavy, chiming yet starrily romantic Slide Away. Engineer Anjali Dutt was subsequently brought into Olympic Studios in London to see if there was anything else that could be salvaged. “I put the faders up, but to be quite frank, they had already decided on the outcome,” she recalled. “I was just there for confirmation. So I sort of went, Yeah, start it again, be bold.”

The other recordings were duly binned, and Oasis were forced back to the drawing board. Aware that they sounded consistently great on-stage, it seemed the best solution was to enlist the band’s live sound engineer, Mark Coyle, to record them in a studio setting. In February 1994, time was booked at Sawmills Studio in Cornwall, where Coyle taped Oasis as if they were playing a gig: close together in one room, no soundproofing between the amps, noise and spill everywhere. Afterwards, Noel piled on numerous guitar overdubs.

Dutt remembered that the group were like a bunch of kids: “They liked sausage and chips and pudding, and they liked to watch telly. And like kids, they were also incredibly hard to get in the same place at the same time, all at once, ready to go. There’d be this brief window of 20 minutes which just about everything happened in. You had to literally slam everything into record.”

I remember Noel pointing to Liam and saying, ‘Look, you’re not fucking John Lennon.’

Owen Morris

This approach was far more successful and foregrounded the band’s inimitable character. The verses of Shakermaker may have brazenly nicked the melody of The New Seekers’ I’d Like To Teach The World To Sing, but that was soon forgotten due to the sheer verve of their collective performance. Similarly, Live Forever may have started life as a Neil Young-echoing acoustic guitar song, but the thumping attitude to the recorded version rendered it unmistakable as anyone other than Oasis.

Still, another problem immediately presented itself. These new recordings brilliantly reproduced Oasis’s thrilling live sound, but Coyle’s mixes weren’t sounding great (due, he admits, to his inexperience in the studio). Enter Owen Morris, who had worked as a studio engineer on Johnny Marr and Bernard Sumner’s Electronic project. Morris had a reputation as a maverick – which clearly appealed to the Gallaghers and the others – and so was given a last shot at salvaging the tracks.

“It was all a bit of a mess really,” Morris remembered. “I was just doing my own thing in the studio, to be honest. I was just ripping off a load of Phil Spector and Tony Visconti moves. As it turned out, it fitted in. But the wall-of-sound was hiding what was there – the drums and the bass were all over the shop. So I had to try to make a record out of it.”

Morris first insisted that Liam Gallager re-record several of his vocals, starting with Rock’n’Roll Star. By this point, with the others sick of the studio process, only Noel and Liam turned up for the lively, capering mixing sessions. “I remember [Noel] pointing to Liam and saying, ‘Look, you’re not fucking John Lennon,’” Morris laughed. “Then pointing to me and saying, ‘And you’re not fucking Phil Spector.’”

The last track in the can was Cigarettes & Alcohol, which was a vivid illustration of Morris’s wayward methods. Where other mixers would have erased all of the noise and sonic crap at the start of the track, he purposely left it in. The result was that it sounded like Oasis were playing in your living room.

“I’d had a few bottles of wine and stuff,” he recalled. “But it kind of works, thank God. It was more luck than judgement that it sounded like that. It was just, ‘Get it down and let’s get out of here and down the pub.’ You could never get away with that kind of stuff now.”

Noel’s only problem with Morris’s final mixes was the solo on Live Forever, which he’d muted halfway through when, to the engineer’s mind, it began sounding like “Slash in leather keks with a wind machine on the Grand Canyon”. Gallagher duly requested the excised bars were reinstated. Thus was preserved one of the most memorable guitar solos in rock.

Ultimately, Oasis, Coyle and Morris worked wonders and the huge public response to Definitely Maybe was near-instant: hitting Number 1, going gold in its first four days of release and becoming the fastest-selling British debut album up to that point. As proof of its mainstream popularity, it beat The Three Tenors (Luciano Pavarotti, Plácido Domingo and José Carreras) to the top spot. Recognising that it was incredible for one of their indie bands to have trounced such a high-profile opera act, Creation put out a statement declaring that Oasis weren’t afraid of “three fat blokes shouting”.

Picture: Michael Linssen/Redferns

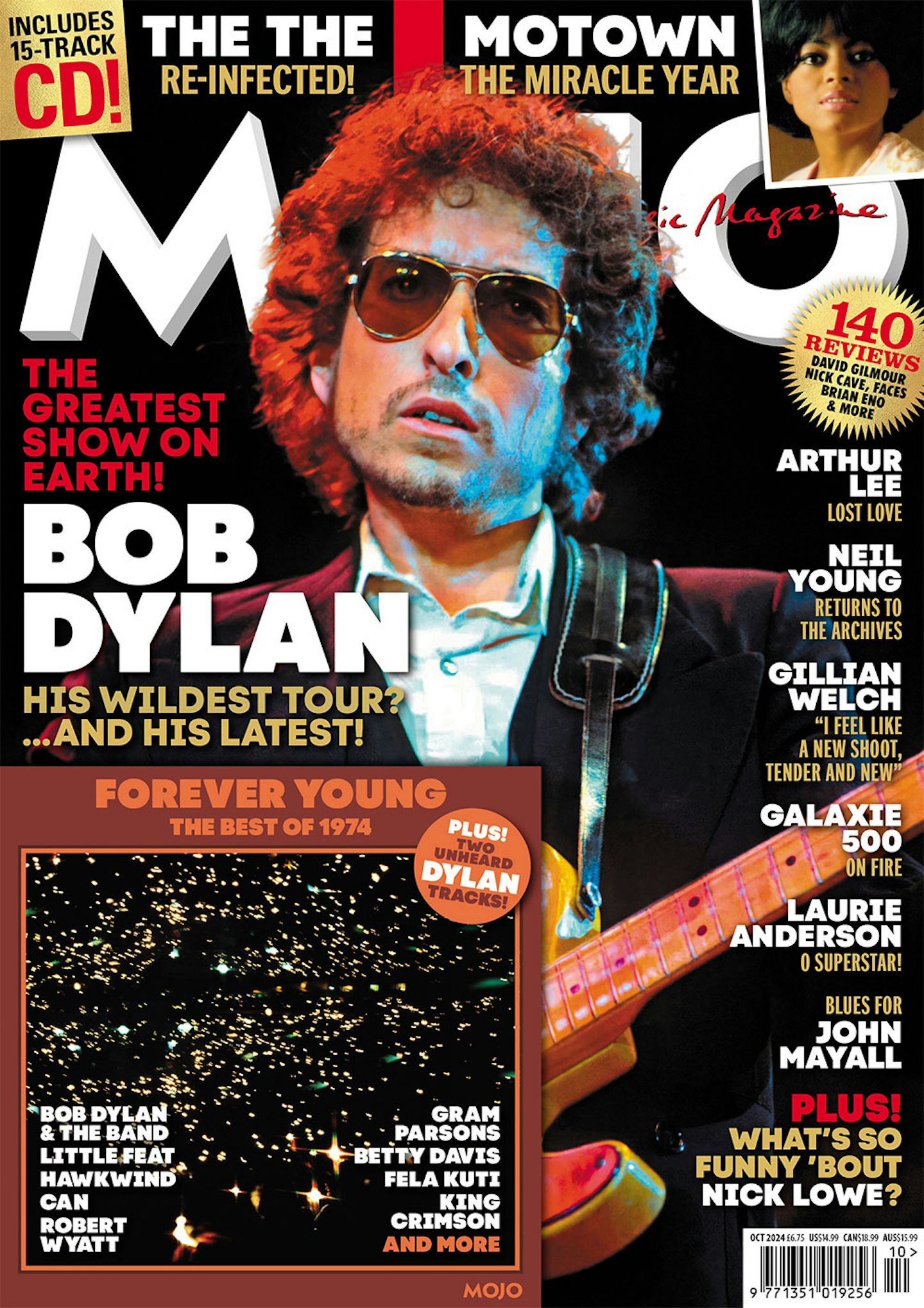

The latest issue of MOJO is on sale now! Featuring Bob Dylan, Motown, The The, Neil Young, Arthur Lee, Nick Lowe, Gillian Welch, Galaxie 500, Laurie Anderson, John Mayall and more. More info and to order a copy HERE!