Carrier of Coltrane’s torch, architect of “spiritual jazz”, life for Pharoah Sanders was as hardscrabble as his voice was transcendent. But as Dave Di Martino discovered in 2021, at 80, as it was at 20, the aim was still the same.

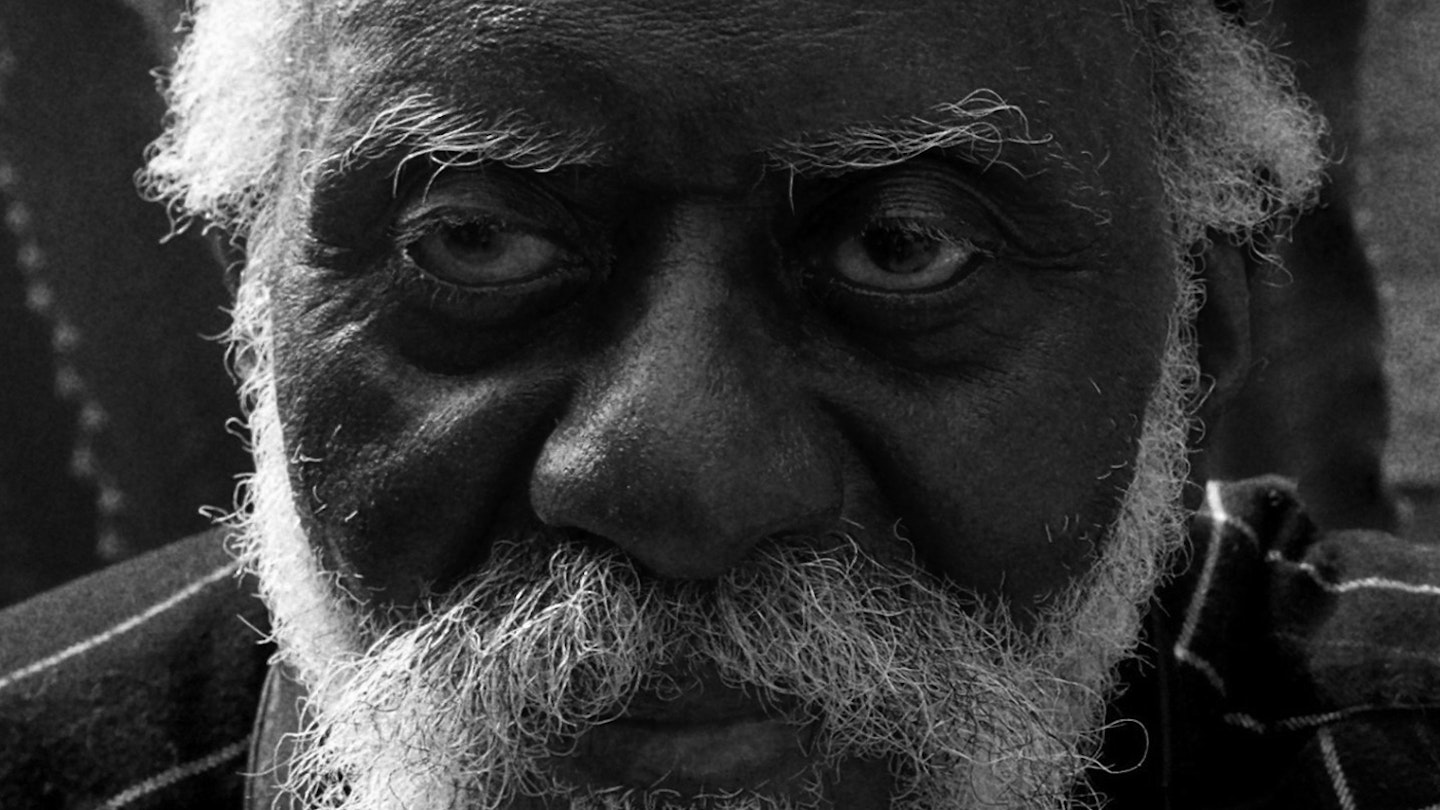

Pharoah Sanders does not consent to a great many interviews. In fact MOJO has lost count of the number of times it has asked for an audience with the legendary saxophonist and been turned down. Sitting in Los Angeles’ otherwise deserted Zebulon club in unseasonable 100-degree heat, wearing a straw hat and with his silver beard gathered in a tuft, he explains his elusiveness in soft tones. “Talking, that’s very hard to do,” he says. “I don’t know how to talk about the music. Just let it play.”

Sanders has earned the right to approach the media any way he likes. Days away from turning 80, he is still performing with the same passion and spirituality that has marked his career. Just a few days earlier, with a band including fellow saxophonist Azar Lawrence, he filmed a 90-minute live performance in this very venue – to be livestreamed on his October 13 birthday. The actual day of filming, September 23, would have been John Coltrane’s 94th. For Sanders, it is a lifelong connection.

After the shoot, Sanders’ band and management had gathered around the saxophonist’s table and presented him with a birthday cake celebrating “Another Trip Around The Sun”. It was a show of warmth and respect for a celebrated jazzman whose dignity off-stage suggests a sternness that doesn’t quite materialise, one-on-one.

In later conversation, Pharoah Sanders is reserved but surprisingly wry, a contrast with the squealing, exclamatory blasts that punctuate the heartfelt excursions of his horn.

Born Ferrell Sanders, he grew up in a religious household in Little Rock, Arkansas, musically inspired but seeking more. In 1959, he moved to Oakland, California, where he would play blues and R&B, and significantly, just across the bay in San Francisco, he would meet John Coltrane. Later, in New York, he’d join the latter for a string of historic recordings including 1965’s bold Ascension, before a series of groundbreaking albums as bandleader on the Impulse! label. Sanders’ 1969 album Karma, specifically the 32-minute track The Creator Has A Master Plan, is revered among today’s crop of young guns – including UK combos Maisha and SEED Ensemble (who gathered for a celebration of Sanders’ music at London’s Barbican Centre earlier this month) – and is often said to have laid the foundation for what is called, for better or for worse, “spiritual jazz”.

Post-Impulse!, Sanders made albums fascinating for their cultural diversity, embracing African music, R&B (1977’s quiet stormish Love Will Find A Way with Phyllis Hyman), and three Bill Laswell-produced collaborations: two for Verve and one in Morocco (see panel). He won a Grammy in 1988 for his work on a Coltrane tribute album, went to Africa in the 1990s as part of a US cultural exchange program, and won an NEA Jazz Masters Fellowship in 2016.

He keeps on, but, as we’ll learn, a living has been hard to maintain.

And so MOJO is brought to a corner table at the Zebulon, air conditioner now thankfully up and running, to settle down with Sanders and Azar Lawrence – the latter to prompt Pharoah stories as needed. The seated Sanders, a cane in his lap, chooses his words carefully. “I don’t have nothing I can say too much about what’s going on right now,” he declares. That he is speaking through a face-covering – as we all are today – makes this encounter even more surreal than expected.

What drew you to music as a child?

Well, really, at that time, it was in church. I tried to go along with singing in church. My mother, she would sing around the house all the time while she was working. I always was really into painting. Music came later on.

What kind of stuff did you paint?

Anything. If someone asked me to do it. I haven’t painted in many, many years, in fact.

So, did you start out playing clarinet?

I started playing drums. But I wanted to play an instrument, like a reed, like a saxophone or a clarinet. I wanted to try them all out, somehow. At school, I would mess around with all of them. Trombone, trumpet, all of them. But it was easier for me to play the clarinet. I used to play the drums and sit around in class beating on the desk all the time. They were about to put me out.

What sort of jazz were you hearing when you were a child?

I wasn’t hearing nothing like that when I was a child, a small child. I wasn’t hearing anything. In Arkansas, we didn’t have too many jazz stations, we didn’t buy records. We didn’t have the money to buy records.

You moved out to Oakland when you were a bit older. Why?

To get out of Arkansas. It was too racist back there for me. I decided to make a move and come to California.

You started playing professionally in Oakland. What sort of music did you play? R&B, jazz, blues?

Blues. I had to learn to play the blues in all the keys. Sometimes you’d be playing with a guitar player, and a lot of times they don’t know what key they’re in. They’d play a note, and I’d ask them what key or what scale, and they’d tell me, “This one right here.” And I’d say, “OK, what is ‘this one right here?’” I knew how to play blues scales and stuff like that, the elements of music. So I started playing, I started practising in every key, and I’d play the blues. Sometimes, if you didn’t know, you’d be lost and you wouldn’t know where to start.

Did those lessons you learned back then stay with you? Do they come into the way you play now?

Yeah, it does a whole lot. I just have to make sure that whatever I play, I mean every note.

I think the first time I ever heard your playing was on the Live At The Village Vanguard Again album [1966] with John Coltrane, and I remember your sound being so incredibly fierce and energetic. Was that raw emotionalism always present in your playing from the beginning? How did that develop?

I don’t know – I’m still going through mouthpieces; they all have a different sound, the mouthpiece and reed combined. I started playing all kinds of mouthpieces, until I felt better. It wasn’t easy, because you had to get a good reed to play – and that wasn’t easy, especially when I was much younger, because I didn’t have the money to buy a reed, so I sometimes had to play the same reed all the time.

You left the West Coast in 1961 and moved to New York. Why did you do that?

Because people were telling me that I should leave and go to New York. They said my sound was “not like” California. “You should go play in New York, learn all the standard songs, get your tuxedo and learn how to work – learn how to live this kind of life.”

I understand it was rough financially for you when you first hit New York. How did you make ends meet?

Well, I did all kinds of things. I was homeless for about two-and-a-half years. I used to give blood. I found out you could give blood and make a little change, five dollars or 10 dollars. In New York, you’d try to buy something like a Snickers or a Baby Ruth, a candy bar, and in New York City it wasn’t just a nickel – you had to add another penny. Six cents. So like I said, I started going to places where I could give blood, and make some little change money.

I know you got some early work in New York from Sun Ra. Did he suggest you change your name from Ferrell to Pharoah?

No, he never did. He never even mentioned it. I read some interviews, somebody said Sun Ra gave me my name (chuckles a little), or something like that. He didn’t give me my name. I used that name before we ever even met, before I’d ever even known about who Sun Ra was. My grandmother, she named me from the Bible. At first, she named me “Pharoah”, then she decided that might be a little hard, getting along with the system, I guess, so she decided to name me Ferrell. So when I moved to New York, later on, I had to join the musicians’ union, and they give you documents to fill out. And one thing I read is that you could have an artist’s name, so I decided to put “Pharoah”, and that’s how that got started. A lot of people used to call me “Rock” or “Little Rock”, until I started recording. They found out what my real name was, but they didn’t spell it right either – they called me “Pharaoh”. They never did know my real name, my real first name.

I listen to everything. Car horns, the squeaking of a door… I listen to sounds, lightning and thunder.

Pharoah Sanders

Tell me a bit about what music you liked when you started out, who you liked, who inspired you, who maybe you wouldn’t mind emulating.

I was listening to Sonny Rollins a lot – I always liked the way he popped the notes out of his horns. He had a good punch. I would go home and study just that. How to use my tongue, how to use my lips, breath control.

You have a very intense, emotional sound. What goes on inside when you’re playing? Are you angry, are you happy, neither? What’s your internal mood?

I don’t know. I listen to everything. (At that moment, a car outside Zebulon honks its horn) Car horns, the squeaking of a door, I listen to everything. I listen to sounds, lightning and thunder.

Back in the early ’60s you were playing with Sun Ra and Don Cherry, people doing avant-garde stuff as opposed to the post-bop coming up at the same time. What sort of feedback did you get from audiences and other musicians?

I was trying to play everything at that time. I hadn’t had no choice – sometimes you have to do things just to make a little money to put in your pocket to buy some potato chips or some nuts. But I always kept a jar of whole wheatgerm in my suitcase.

When you were starting out, did you pay any attention to what critics were writing about your music? Did you care?

It didn’t bother me at all. I’d look at it, and read, and went on from there. I kept on playing and I kept on practising. I wasn’t into somebody talking about the way I play or what I do. I knew what I needed to learn, so I kept to doing that.

Pharoah [1965], your very first record for ESP Records, was once very rare. Now it can be heard by almost anyone who streams music. I understand you weren’t exactly thrilled with the album at the time. What are your thoughts about it now?

Well, at that time, you’re using your talent, and [the label] felt like they liked it, so that’s all it meant to me. If they liked it, they liked it. They never paid me no money, but they liked it. So I was still trying to find some jobs around town. One time I played piano at a club and nobody showed up, but I had to play in order to make 10 dollars.

How did you come to join forces with John Coltrane?

I don’t know. I don’t think I was ready to be playing with John Coltrane. I always loved his music and I loved his style of playing. I never felt like I should play more than he played when he hired me – I’d always stand back and let him play more than me. I always wanted to get my own band together, but it was hard to do; it was hard to keep a band together. I did many other things. I worked for Macy’s for a while, for Macy’s warehouse.

After Coltrane died, you made some fascinating records with his widow, Alice. What was that like, what was she like?

Alice? She wanted to keep the music going, you know, and her husband left a whole lot for her to do – it was for her, for whatever she wanted to do. They had three kids, I think, and she had to take care of them, so I’d never talk to her that much. I didn’t know her like I knew John. She had called me sometimes for a record date, once in a while ask me would I do something with her.

You released a very impressive and diverse string of albums on Impulse! on your own, starting with Tauhid. What was the strategy there, what was the intent?

I was trying to let people know what I can do. I never did get credit on that particular record [Tauhid] – because I played alto and tenor [it’s credited on the CD release]. I guess it sounded like I was playing tenor – they didn’t know the difference in pitch or whatever.

How did you select the musicians that appeared on your albums? Were they a working band, or

did they come in specifically for the session?

They’d heard me and always had said, “I’d like to play with you sometime, if you need a drummer, a bassist, a piano player, a conga player, I’d love to play.” I didn’t have no jobs for anybody. But I think they heard me play, and they might’ve liked something I was doing.

Tell me a bit about working with Leon Thomas [vocalist on The Creator Has A Master Plan].

When I first heard Leon Thomas, there was a place in Manhattan, downtown, called St. Mark’s, I think – a jazz club, classical, whatever they’d play. I met [Coltrane drummer] Elvin Jones, he was just sitting there, and Leon Thomas was there, singing, And I asked [Thomas], “Would you mind playing with me on a job?” I was looking to get a job at a club on the East Side called Slugs’. He reminded me so much like an instrument, with his voice, and I wanted to use him. And it seemed like everything went well; he decided to work with me for a while.

I was homeless for about two-and-a-half years.

Pharoah Sanders

Artistically, how appreciated did you feel? Were people listening?

For me myself, I always felt like I wasn’t really good enough with what I was doing. So I kept trying to find out information – what I needed to learn. Do I still feel that way? Yeah. Gotta learn. Every time I listen to somebody, they do things that I wish I could do. Everybody’s got something different to say. So it kind of messed me around – I started feeling, maybe I should’ve started playing piano first, instead of sax.

Do you hear your influence in other players? I’m sure Azar here can.

I like the way Azar sounds, I love that kind of sound. I used to ask him why he’s around here in LA – I didn’t think it was too good to be playing and working here in LA. Because sometimes you have to find your personality, at some point, what you’re going to do. When I was in Oakland there were many players, good players – like Smiley Winters, he used to play with Charlie Parker – they told me, “You should go to New York.” I didn’t know what they meant by “go to New York”, I was still trying to study and play music.

You spent some time overseas. Was your international appeal different than it was in the States?

It seemed like people in other countries were far advanced, listening to what they wanted to hear – young, old and all ages. It surprised me, you know? And I’d come back over here and it was very different. Plus, it really helped me because they paid me, and that really helped in my everyday. So I kept wanting to go back over. People like Archie Shepp, a lot of freelance people, they’d go there and were working many, many years before I went over there. I didn’t start going over there until maybe in the ’70s, late ’70s, I don’t know. I just didn’t know who to hook up with as far as the agencies. I didn’t know anything about the agencies. Ornette Coleman, I learned a lot from being around him. He’d be telling me, “You can go and they pay you a little bit more money.” I didn’t understand. I said, “Really, I’m ready if they want to send for me.” I didn’t have a passport or nothing – so I finally got a passport and I seen what they were talking about. And you know, they paid me pretty well, but at the time I had met Ornette Coleman, he told me, “You should be able to get a whole lot more than this,” and so I learned from him. That he wouldn’t never go over there unless he got what he wanted to get. So I had to learn to make them respect you, and the price that you say will get you over.

You reappeared on Verve Records in the 1990s in the States, at least briefly. How was that for you?

I didn’t actually sign with them. You know, a lot of things I kind of did wrong. I started out sort of late. Verve kept calling me, wanting to do something. They mentioned Bill Laswell – he could produce me or whatever that was. But he didn’t do it right. They had given him the money that was needed, but he waited a long time, I guess. Apparently they were a little bit angry with him.

You are considered one of the giants of what is now called “spiritual jazz”. What would you say “spiritual jazz” actually is

Well, I always look at music as a kind of very spiritual thing anyway. So I never have to go to it. It is all around me.

Has anyone new caught your ear recently? Anybody you’re especially impressed with?

Well, you know, a lot of people are doing a lot of things new. I love Azar, the way he plays. A lot of players around me, they play very different – Azar, he likes to express, and he seems to be a very inventive kind of person, and I listen to it and I say, “Yeah, that’s great.”

Are there any musical areas you haven’t explored yet that you’d like to?

Well, it comes and goes, you know. Me, I would like to go to India and study the music over there. Maybe, if possible, play with them. Learn the scales and whatever else I have to learn in order to play. I always like to do more of a cultural exchange, playing with some bands in other countries. I like to listen to them, but I never played with them. I played with [Indian percussionist-composer] Zakir Hussain, I love his playing. I never played with too many sitar players – I’d like to play with them. I always feel like I should get my soprano saxophone out and start playing. My soprano’s been in storage about 10 or 12 years. I remember when I couldn’t take my soprano on the airplane, they gave me problems and problems. I thought, Well, I’ll just leave it at home, and I’ll try to make my tenor sound like a soprano.

With the Covid-19 situation, how has life changed for jazz players?

I think we’ve all been at home, maybe writing more music, maybe practising more, staying healthy. But you can be trying to play some beautiful music, and you still have to go out and make a little money energy or something to help out. Because there don’t be too many places you can get food free.

I see you’re walking with a cane – how are you holding up physically?

I’m doing OK. In March, I was coming out to work with Joey DeFrancesco, and I fell on my right side and I broke my hip bone. I got up and I thought I was OK, but I tried to walk a few steps and I had to crawl back into the house.

I couldn’t make it. So ever since, I’ve gotten a whole lot better, and started healing, and then I got this cane stick, because you might fall again. I can’t be doing that.

What do you think is your greatest accomplishment as a musician? What are you proudest of?

I was brought up in a very, very religious way by my mother – I was the first one at church every Sunday – so I’ve stayed into the church, I’m that kind of person. And I’ve always loved the music, and I just went in that direction.

And when I heard jazz, I loved that, too. It was like another kind of a classical music, a very intelligent way to play music. In some ways you can play music that’s maybe not so intelligent – and keep digging, keep digging, and then feel something [deeper] that’s going to come through. So I decided to stick with what’s called jazz music – black classical music.

Think you’ll ever call it a day playing music?

That’s what we got now, unless they’re going to pay me enough money to come out of the house. I feel like I have retired… (his raised eyebrows suggest a grin beneath his mask) …from getting low pay!

This article originally appeared in MOJO 326. BECOME A MOJO MEMBERtoday and receive every new issue of MOJO on your smart phone or tablet to listen to or read. Enjoy access to an archive of previous issues, exclusive MOJO Filter emails with the key tracks you need to hear each week, plus a host of member-only rewards and discounts. The latest issue of MOJO is in shops and available to order online HERE.