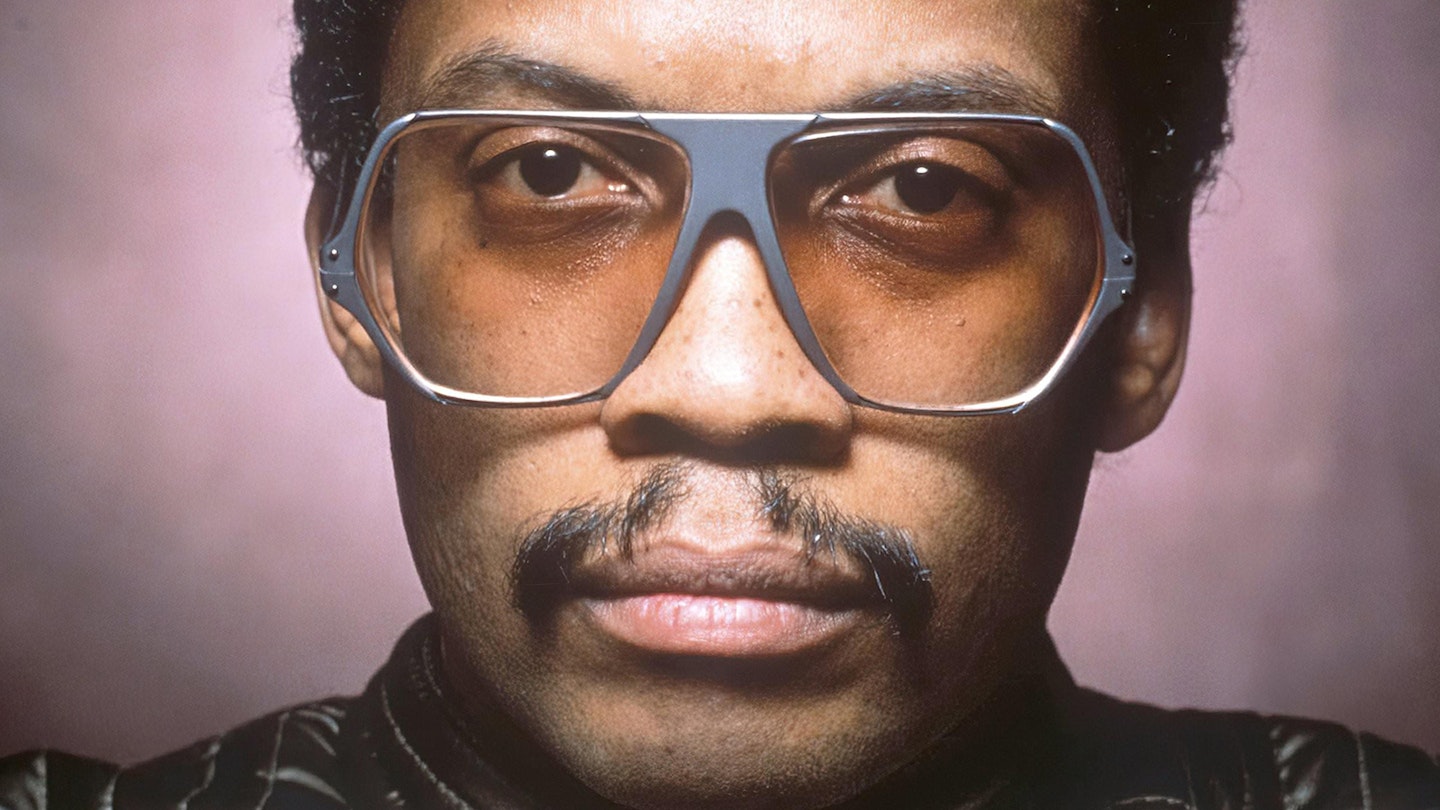

A scientist’s innate curiosity led him to Miles Davis, great ’60s jazz, ’70s fusion and funk, ’80s hits and a 2008 Grammy. In 2010, MOJO's Geoff Brown sat down with Herbie Hancock to trace the career path of one of the most important musicians of the 20th Century...

Friday, mid-June. New York simmers, but up in his Essex House hotel suite on Central Park South Herbie Hancock looks extraordinarily cool for a man about to celebrate his 70th birthday with a concert at Carnegie Hall. Red hues dominate a subtly striped shirt loosely tucked into black slacks. As if to dispel the aura of sleek, he looks down. “Every time I eat,” he says, scrubbing away at spots of food, “my trousers become a tablecloth.”

Even so, Mr Hancock, looking good… “Well, granted I dye my hair,” he laughs. “You know what started me? When I did the film Round Midnight [1986] I had to play a character younger than myself and a character older than myself. My hair was already like salt-and-pepper so they dyed it. I remember sitting in front of the mirror and as it’s getting blacker and blacker I’m seeing the years fall away, and I say, I think I like this! So ever since I’ve been dying my hair, because to play the older character they made it more grey, and somehow that didn’t really take with me,” he laughs again.

What has been unquestionably immaculate is the career commemorated by 7 Decades: The Birthday Celebration, which would reunite Hancock with fellow Miles Davis alumni Wayne Shorter (sax) and Ron Carter (bass), as well as with musicians who’ve worked on his very latest album, The Imagine Project. Perhaps even more than Miles, Herbie has combined a career of questing, innovative and satisfying post-bop jazz with one of a more openly, sometimes defiantly commercial aim. Consider this: He began his solo recording career as a jazz pianist by writing a Number 10 US pop hit just as The Beatles first broke into that chart. In an extraordinarily prolific ’60s he combined his own ever-evolving recording career with groundbreaking music in Miles Davis’ band from 1963’s Seven Steps To Heaven to 1972’s On The Corner, in a quintet that took jazz from post-bop to the threshold of jazz-rock and funk. “Herbie was the step after Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk,” Davis wrote in his 1989 autobiography, “and I haven’t heard anybody yet who has come after him.”

After more jazz-funk explorations, he invoked the indignation and fury of purists with dance-pop confections such as I Thought It Was You (1978) and Rockit (1983), all the while seeking out new innovations in keyboard instrumentation and technology.

“I’m adventurous anyway,” he explained early in our interview. “It comes from my innate curiosity, which led to me being interested in science. It’s a scientist’s attitude to be curious. I was an engineering major in college, so I was always curious about stuff, but it’s expanded from being curious about how things worked to also about humanity and people, and that’s due to my practice of Buddhism.”

For the open-minded the rewards in Hancock’s long and varied career have been frequent and immense, be it his VSOP recordings, which reunited that legendary Miles Davis band, or the acoustic piano duet LPs with Chick Corea, a separate catalogue of work as a sideman, the composition of a portfolio of jazz classics and a recent clutch of guest-filled concepts. To squeeze this astonishing career into the allotted 60 minutes was going to be a challenge…

Clearly, you must have started young. Was getting a proper music education important?

I had been playing music since I was seven. I played classical music but also listened to rhythm and blues because I lived in a black neighbourhood so that was the music that was happening there. And I’m from Chicago so I heard the real blues, Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf and a bunch of others.

At just 11 you performed Mozart with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Tell me about your classical music teachers.

The first one [Mrs Whalum] taught me to read,

I could read pretty good, but there was no feeling. The second one [Mrs Jordan] was about feel and she taught me how to play Chopin and Debussy and things that are more sensitive.

And for harmonics I read you taught yourself from vocal groups?

It was The Four Freshmen first, that was during high school. By the time I got to college The Hi-Lo’s were like an extension of that, harmonically much more advanced. I used to listen to this radio station in Chicago to this guy named Al Benson. It was basically an R&B station but once in a while he would play something of jazz. I remember hearing The Hi-Lo’s on that station and their harmony was different than barbershop harmony, which was the only kind of vocal harmony I had heard before. So that’s when I learned about major sevenths. But I learned harmony in theory, the basics of it, by hanging out with other musicians and asking them questions. They taught me how to read chord changes. So by the time I got to college and studied harmony I knew all the stuff… I would just show up for the exams, get an A (laughs) and walk out of the class. I knew that stuff from learning from the streets.

Your interest was piqued by West Coast cool but you switched to hard bop. Good move.

Well, the school I went to, at that time, 10 per cent of the students were black, some Hispanics too, so it was primarily white students and it was some of the white guys that turned me on to jazz, and they were listening to West Coast jazz. Although the first person I listened to was George Shearing, because the guy that actually stimulated my curiosity [about jazz] was a piano player. I heard him improvise and I didn’t know anything about improvising. So I wanted to learn how to do that and he was listening to George Shearing. Then I also listened to Erroll Garner, and Oscar Peterson. Then I met some other guys in high school who were listening to West Coast jazz, there were maybe three or four guys. Jazz was almost underground because everybody else was listening to either R&B or the Hit Parade, which was the white pop music. So that’s kind of what I heard first, Stan Kenton and Pete Rugolo and Shelly Manne, Chet Baker, Shorty Rogers. I remember one of the guys saying, “Yeah, the cool West Coast jazz, this is great stuff to listen to, not that hard bop stuff.” I remember him saying that. Then one day I saw a record and the name of the record was Hard Bop. “Oh! Maybe this is what he’s talking about, let’s see what it is.” I listened to it and, “Wait a minute! I like this!” (Laughs) It was Bill Hardman and Horace Silver, musicians from Philadelphia and New York, and I liked it more than I liked the West Coast jazz so I started pursuing that. All this happened in a two, two-and-a-half year period and that’s how I got into Count Basie and big bands.

With all that going on before you got to college, why choose engineering?

When I was 14 I started playing jazz [high school] and then I went to college when I was 16, I was young. The reason I decided to do engineering was because I was interested in both science and music and I decided to be practical. Could I get a job as a musician? Mmm, I don’t know. Could I get a job as an engineer? Definitely yes, back then.

Did your parents have an input?

No. My parents told my older brother and my younger sister and I, whatever we wanted to be they would support us. We decide what we want to be, which is great. They wanted to be real progressive parents. So my choice of engineering, they were very happy about that (laughs).

You were always interested in technology, physics, engineering. How did you come to give up that ‘security’ and switch to music?

At the end of my second year of college, jazz was pulling me in like a really strong magnet. [It] was occupying the time I should’ve been spending studying physics and math and stuff, which I still love. At the end of the second semester of my second year I decided, I wanna put on a jazz concert with a big band. (Laughs) I went to school in Iowa [Grinnell College]. Where you gonna find a jazz musician in Iowa!? They’re farmers! It’s corn! Some had played in a dance band in high school, some played in a marching band in high school (laughs). Anyway, I got together five saxes, I think four trombones and five trumpets. There were two guys that could actually play trumpet and improvise. Two. The rest of them were, like, total beginners. I took a Neal Hefti arrangement for Count Basie (hums Cute), something like that, and I tried to figure out what all the musicians played. I had no idea that what I was doing was amazing ear training. So I wasn’t going to classes, was flunking everything and knew that to pass I had to ace all my finals. So the jazz concert was a big success and then I went into cram mode. I got three As and a B, so I passed. But then I remember going into my room and looking in the mirror and saying to myself, Who are you trying to kid? The next day I changed my major to music composition.

“I was flabbergasted when Miles Davis called me.”

Contrary to your earlier fears, you found work as a musician fairly quickly.

During the summers I [had worked as] a postman, so when I graduated I went back and delivered mail until I got a call from a drummer, Louis Taylor, “Coleman Hawkins, he’s coming to Chicago next week and Jody Foster [the number one pick for jazz pianists in Chicago] is busy so I recommended you.” So I got to play with Coleman Hawkins, every night for 14 straight nights. We worked from nine in the evening until four in the morning and I had to be at the Post Office at eight in the morning. Saturdays we worked to five in the morning. It was crazy. I lasted three days. I was getting fever, I was sick, the drummer came over and said, “Hey man, quit the Post Office, it’s interfering with the music, I know you can do better.” So the third day I quit the Post Office. That was a big decision. After those two weeks were over I was sitting waiting for the phone to ring. I was living with my parents so it wasn’t a dire emergency but I was out of college and didn’t want to depend on them. Then a few months later Donald Byrd came through Chicago with his band and wanted somebody for the weekend. That weekend extended to me moving to New York with him (laughs) and I played with him for two years. And then I joined Miles Davis.

Donald Byrd was a renowned teacher/mentor.

I was 20 when I joined Donald’s band. He was still in his twenties, ’cos I remember when he turned 30. I told him, “Can’t trust you any more, you’re 30!” He just laughed. He was like an uncle to me, I think he was working on his Masters degree already. Donald studied music education so it’s really part of his DNA to be a teacher and the idea of him kind of raising young people is natural to him. He kind of took me under his wing.

You were only 22 when you started making jazz albums for Blue Note as a leader. How did that come about?

Donald Byrd said, “OK it’s time for you to do your own record.” I said, “No, I’m not ready.” He had already called Alfred Lion and Frank Wolff, who owned Blue Note, and alerted them. So he talked to me, “Call them up and say you want to make your record now because you’re being drafted –we had conscription then – and you want to make your record before you go off to join the army.” They were known for really supporting young musicians. Donald told me, “Here’s the secret to making a record on Blue Note – half the record is for yourself, and half the record is for the company.” What does that mean? He said, “Well, half the record is your compositions, and the other half is to help sell the record.” The implication is, what’s gonna help sell the record is something that’s familiar to the listeners. It could be a blues tune, a cover of an old standard. So I took his advice. I wrote three compositions to play for them to get their approval first. But in the meantime I thought, Horace Silver writes original songs, and they sell his records. So what is it about Horace’s songs that makes them appealing? They’re funky. Well, maybe I can write something funky. I came up from rhythm and blues, it’s my background. So I’ll try to write something, you know, ethnic. Funkiness really comes from the African American heritage. So I said OK, I don’t wanna write a, quote, commercial tune just for the heck of it. I want it to be real. I’ve heard songs about chain gangs and, you know, working in the fields. I’m from Chicago, I never did any of that (laughs). What can I find that’s accurate from my own experience that I could write about? And the thing that kept hitting me was the watermelon man. Because he used to go through the cobblestone alleys of Chicago with a horse-drawn carriage on wagonwheels, not tyres, and that rhythm came from me thinking about that (voice and finger-clicks create the riff’s rhythm and melody) and ladies would yell out from the back porch, “Hey! Watermelon man!” And he had a little song he sang. I decided to write something to try to capture that essence in a song, because that was true.

You must have thought, Hey this is easy!

It took 15 minutes to write. So that was one of the three pieces I presented to Blue Note. OK tomorrow I’ll bring three other pieces, a blues, a cover of a standard and something else. They said, “No, why don’t you bring three more of your compositions.” That was really unusual [for Blue Note] for a brand new artist to have all their own compositions. The record [Takin’ Off, 1962] came out, at that time they only had one chart so it got up to like 84 on the charts that had, like, pop, country, everything was on the one chart which, in a way, I wish it were like that now. I think it came out in September of ’62, and in December of ’62 I worked with Mongo Santamaria over a weekend, and it was there, thanks to Donald Byrd again, that I played the tune for Mongo during a break in the gig I had with him. He got up on the conga drums, and it just fit. The band got up one by one, they joined in. It was a supper club and very few people had danced. When we got into Watermelon Man, they all got on the floor and everybody was dancin’. So Mongo asked, “Can I record this?” I said, “Absolutely!” It got to Number 10 in the charts, 1963, that was the year The Beatles was on the charts. It’s funny I saw Paul McCartney, (puts on official voice) ‘Sir Paul’, about two weeks ago and we were talking about the old days being in the charts in America at the same time. It was a first for them and a first for me.

You mentioned earlier another defining moment, joining Miles. What impact did Birth Of The Cool have on you?

Oh man. I had never heard anything like that before. It fascinated me because here we have a mixture of instruments that were traditionally classical instruments and jazz instruments, and I loved the sound of them. But what really did it for me was when I heard the first record of Miles Davis with Gil Evans, Miles Ahead [1957]. When Miles Ahead first came out, I cried because it was so beautiful. Even to this day I can’t help but well up inside listening to it. Only two records did that for me, Miles Ahead and Stravinsky’s Rite Of Spring. Either one of them, I well up. They both touch me deeply.

So you got the call to work on Miles’ Seven Steps To Heaven in 1963?

The music was demanding, but it wasn’t like Miles was some strict taskmaster. I was just excited about playing at that level. Even when I was in Chicago, Miles came and I met John Coltrane, [pianist] Wynton Kelly and [drummer] Jimmy Cobb. When I went to New York with Donald Byrd’s band, after a few months Donald Byrd took me in to be his room-mate in the Bronx, and Jimmy Cobb lived a few doors down from us. So I saw Jimmy a lot.

Seven Steps was half finished with another line-up when Miles called you in…

Yeah but I didn’t know about it at that time. Ron [Carter, bass] had already been in that kind of interim band and George Coleman had been, but the new people were [drummer] Tony Williams and myself and we were invited to Miles’s house the same day. Tony, actually, we already had bonded, we had been doing a few gigs with Jackie McLean and a few other people before we joined Miles. Tony was a phenomenon. The number one drummer at that time was, er, um, [Elvin Jones?] Elvin! Right. But Tony had something that was even beyond what Elvin was doing. And so I understood Miles wanting Tony. Everybody wanted Tony. Plus Elvin was with Trane and Trane’s band was like a match made in heaven (chuckles). I knew that Tony was the thing Miles would want. I was flabbergasted when Miles called me. But I knew I was working in some areas that were fresh and new too, it wasn’t well-formed, I was still getting it together.

How did the band that recorded Mwandishi come together in 1969?

That was a combination of the influence of the avant-garde, which then was getting further and further out from the band that originally started off playing very gentle things like Speak Like A Child and Maiden Voyage. The instrumentation remained the same, that was an influence from Gil Evans and Miles, but the exploratory nature was getting further and further out, more spacey and intuitive, and at the same time the civil rights movement was happening and we were affected by that, and by John Coltrane too, his spiritual kind of compositions, Love Supreme, but also the anger at oppression and discrimination. So that kind of lasted to Mwandishi. The name meant The Composer [in Swahili]. I wanted to show some kind of solidarity with my roots as an African-American. And, of course, James Brown had come up with Say It Loud, I’m Black And I’m Proud, it was a whole new thing for African-Americans.

And after three albums you reconfigured your style into the funkier Head Hunters.

Well, the band had gone further and further out. Even so we had a synthesizer the last year in the Mwandishi band so that was just starting to come in. That was just a new way to make new sounds, which fits in with avant-garde. But I got tired of that. There was something else I needed, that I was feeling was missing.

I mean, it hadn’t been missing until it was missing (laughs). It was fine, and then at a certain point it was just something else that I needed to do. I needed an earthiness. Also my taste was taken by Sly Stone, I wanted to

do something that was kinda funky and related to the R&B I was brought up with, and jazz too. And that’s when I did Head Hunters.

Later, you embraced synths and a more commercial approach ending in pop hits like I Thought It Was You and You Bet Your Love.

Well, everybody wants to reach more people. Even when we were avant-garde we wanted to reach more people. That’s why we added the synthesizers, because it was an instrument that had just entered the scene with rock, the MiniMoog had come in. You always want to reach more people, but with music that is motivating you at the time. So when Head Hunters became a hit all of a sudden there’s a whole new audience available to me in addition to the fans I had before from jazz. I might as well take advantage of this opportunity and so we continued to pursue that direction, it was evolving and expanding in a lot of different ways. To me it was a natural progression, again with the Vocoder and everything, with new technology which related to my science background. I got my first computer 1979, Alpha 2 Plus, and I encouraged other jazz musicians to get into computers and so forth, even when they were reluctant.

Alongside that you’ve always had acoustic things, like VSOP, the acoustic Miles rhythm section reunited, and duets with Chick Corea.

There was a concert in, I think, 1976 here in New York that was supposed to be a retrospective of my work divided into three periods. One was the Blue Note phase along with the Miles Davis period; one was the Mwandishi period; and the other was the Headhunters period. We put a band together to kind of represent the Blue Note and Miles [eras]. The concert was called VSOP and we made a record [of it], but there was such an interest in that combination of musicians [the Miles band] that we thought, Why don’t we go out and play, do a tour, just one, see what happens? That tour wound up not just one tour, but went on for several years. And I would do VSOP things and Headhunters things together.

The Imagine Project sounds of-a-piece with your more recent albums like River: The Joni Letters(2007) or Possibilities (2005).

Sonically, I understand what you mean. Motivationally it’s very different. The motivation started with me thinking, “Why do I wanna do a record?” Years ago I never used to do that, but I guess through getting older and hopefully wiser I think about purpose first. The answer should always be to address something that serves humanity somehow. Anyway, I decided to do something that addressed an issue of today. And the first thing that popped into my mind was the economic crisis – that was before the [BP] oil spill. That triggered globalisation, because the average American, I don’t think, ever had a concept about globalisation. Thing is, it’s already here. When they talked about the banks being too big to fail, it’s because they’re international. Globalisation is already here, but am I going to sit around and just complain about it, wait for the horrible inevitable or are we gonna get up off of our butts, be proactive and create the kind of future we want?

Can music do anything about these things?

Music is powerful. I remember this guy came up to me and thanked me for writing Maiden Voyage. I said, “Why?” He said, “If it wasn’t for Maiden Voyage I wouldn’t be born.” (Laughs) But look at We Shall Overcome, how powerful that was in the civil rights movement. We Are The World, how powerful that was. Hitler even used Wagner to energise the troops. I like Wagner, don’t like Hitler, but Wagner is great. So we know music is powerful. Celebrity is also powerful, but it has no value unless it’s used to serve humanity.

This article originally appeared in MOJO 203.