In 2010, for the 200th edition of MOJO Magazine, singer-songwriter and producer Joe Henry sat down with Harry Belafonte to discuss one of the most remarkable lives of the 20th Century. From leaning from Leadbelly, giving Bob Dylan his first break, marching with Martin Luther King Jr and beyond…

I was a boy of seven living in Atlanta in 1968 when Dr Martin Luther King, Jr was shot dead in Memphis, Tennessee. He’d gone there to speak and show solidarity with the striking garbage workers of that inflamed city. But every city was aflame that year. And his death must have seemed as inevitable to him at that turbulent moment as it was to most of the nation, though so many of its citizens were hoping, praying otherwise. Dr King had crossed a line in Memphis, as he had exactly one year earlier at Riverside Church in New York City, where he’d defied many of his supporters and even some in his innermost circle by going ‘off topic’ from a strict civil rights agenda to include indictments against the United States of America for its conspiracies with poverty and violence – in particular, its prosecution of a war in Vietnam. Once King had equated the American soldiers in South-east Asia to the striking garbage workers – allowing that they were both doing the dirty work of the US government – it was, as they used to say, all over but the shouting.

Dr King was killed in Memphis, but he lived with his family and led a church in Atlanta. I remember not only being sent home from school early that fateful day, but remember too sitting around our flickering television set (they used to flicker) watching the funeral parade taking place a few days later and only a few miles away through the downtown streets of our enraged, heartbroken city.

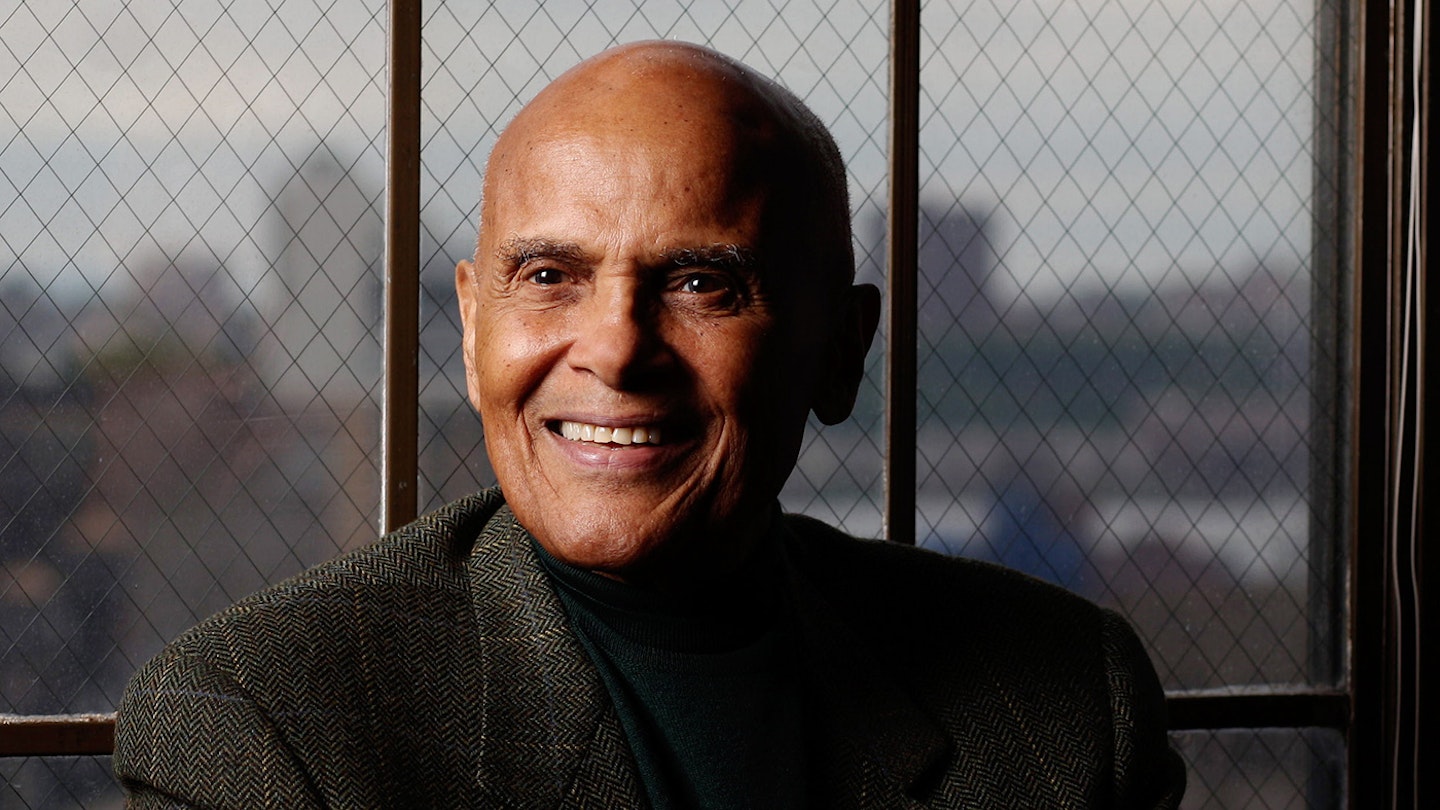

I remember the anger and the tears, the fear and confusion, and I remember a defiant man – a handsome African-American, with a pronounced widow’s peak – leading his friend’s casket through the streets, streaming tears but looking oddly serene, as if possessing some secret vision of things yet to unfold.

His head was high and thrown back.

He was singing.

-

READ MORE: Harry Belafonte's Greatest Albums

Harry Belafonte was born March 1, 1927 in New York City, to a teenage housekeeper. As a young boy he was sent back to his mother’s native Jamaica to be raised by his grandmother, though upon returning to New York at 13, he would never again call anywhere else home, even when maintaining houses around the world. He would become one of the biggest-selling recording stars in history, though he hadn’t originally aspired to be a singer at all. He was an actor, and a classmate of both Marlon Brando and Tony Curtis in 1946 at The New School’s acclaimed Dramatic Workshop.

Harry and Marlon capped many late evenings after class hanging out at The Royal Roost, a small but pivotal jazz club in midtown Manhattan, where they befriended elders like Lester Young and young upstarts like Dizzy Gillespie. At the end of one such night, Young asked the two students, “Well, you see what we do every night… what do you cats do?”

In response, Belafonte invited a group of the musicians to come see them in a staging of John Steinbeck’s play Of Mice And Men. Harry sang during the performance, and that inclined one of the musicians in attendance to goad the young actor into coming down to the Roost at dinner hour and singing a few standards for tips. Reluctant but broke, Harry agreed, and spent several days rehearsing three songs with pianist Al Haig. On the evening of his singing debut, as Harry and Haig mounted the stage, they were spotted by Charlie Parker, who would be playing with Haig later that evening. Upon seeing his piano player, Parker grabbed drummer Max Roach and spontaneously joined Haig and Belafonte. The resulting performance was, for Belafonte, a disastrous free-fall, as Pennies From

Heaven turned swiftly from a cocktail ballad into a bop manifesto.

It might have proved both the beginning and end of Belafonte’s foray into music, but not long afterwards he chanced upon the great folk/blues singer from Louisiana, Huddie Ledbetter (better known as Leadbelly), at the Village Vanguard. In the course of an hour’s performance, Belafonte was initiated into the power and immediacy of folk music – not just as entertainment, but as a vehicle for narrative, political thought and extended community. Next up came Leadbelly’s friend Woody Guthrie, with his wiry frame and knotty verses so keen to the moment that many were still unfinished when he sang them off the crumpled page.

Then, in the waning days of the 1940s, Paul Robeson entered Harry’s circle of influence. Robeson was a star not of the bohemian circuit, but a mountain fully formed on the mainstream horizon, who nonetheless radically insisted that his artistry, personal convictions and political consciousness were all one seamless piece of fabric…

And then in 1956 came Dr King. On his first meeting with Harry, around a card table in the basement of Adam Clayton Powell’s Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem (an encounter scheduled to last 30 minutes, and one that stretched into a summit of nearly five hours), King enlisted the rising young singer into a lifetime of non-violent activism, and into a friendship that is still palpable today, more than 40 years after the good reverend’s murder.

And time marched on. Harry Belafonte became a sensation, then a bona fide star. The star found his voice, the voice spoke and sang, enthralled audiences and confounded them. He confused entertainment with message, breaking colour lines, smiling warmly while singing out loud about ringing hammers and a coming revolution. He made movies. He marched and rallied, he fought dogs, fire, and violence, he lost friends and won battles. Introduced Bob Dylan on record. Stood with Mandela. Got drunk with Castro and García Márquez. Survived a brutal era that he helped define, then lived through another one. Then another.

That’s basically what I knew, a year and some months ago, as I walked against a wet, blowing, ear-numbing snowfall in Manhattan, cutting across the grounds of the Museum Of Natural History, making my way from 81st Street and Central Park West to the low 70s and Broadway. I had been invited for coffee to the apartment of Harry Belafonte, a man I had never met but for whom I have long held a great admiration, both musically and socially. The impetus was a documentary film about his life that he was working on and that he wanted some music help with. In truth, we talked very little about music that day. Barack Obama had only two weeks before been sworn in as the country’s 44th president, and talk quickly turned to his inauguration: what it meant and didn’t, shouldn’t, wouldn’t, and might.

I sat with Harry in his living room and watched a rough assembly of his documentary-in-progress. When the grainy black-and-white footage of Dr King’s funeral march through the streets of Atlanta in 1968 arrived, it inspired a Billy Pilgrim “unstuck-in-time” sensation: I saw what I first took to be the dark and ancient past, then realised that the archival footage was not only a moment from my own lifetime but, shockingly, one for which I had been physically present. The handsome singer with widow’s peak whom I had glimpsed so long ago walking with his friend’s coffin, head held defiantly high through song and tears, now extended his comforting hand to me as I faltered and wept, unexpectedly reliving that terrible ‘ancient’ history – his, mine and ours – as if it were yesterday. Or, more accurately, as if it might be tomorrow.

“Are you all right?”

By gently asking me if I was all right, Harry Belafonte told me that I was, such is his abiding presence and authority. He hasn’t the power to ensure that anything will be as we might prefer it, I don’t mean that. But it’s never been about preferences, and won’t be. Harry Belafonte’s music, acting, producing, philanthropy, social presence and political activism have become indistinguishable, each from the others: a seamless whole piece of fabric stretching across decades, speaking always and only to forward motion. As an artist Belafonte is using his humanity to bear witness, to illuminate and magnify, to do what all artists are called to do, I believe: to place his beating heart next to another’s…

To walk and sing. To speak and rally, fight, win, lose and wonder. To survive. And then to continue.

Harry Belafonte and I have climbed into deeper water since that first meeting, having now recorded together (a duet between Harry and the great Baaba Maal, for which I played producer, intended for Harry’s documentary film) and having travelled in tandem through Berlin, Paris and London earlier this year, researching yet another film project the man is developing (tentatively titled Another Night In The Free World). But having seen his day-to-day person, I live no less in awe of his history, no less enamoured with his journey and the future he spies off the front of his ship. I jumped at the chance, then, when asked to inter-view him for these pages, and do so here with all due respect and a fair amount of bafflement. He is, after all, like his true mentor Paul Robeson before him, a mountain. And whether you know it or not, he has changed things for all of us.

Everybody’s grandmother loves Harry Belafonte, everybody’s wife and mother, and nearly everyone I know grew up with your records in their house. For many of us, you’ve always been part of the cultural tapestry and, as such, people feel entitled – even invited – to make assumptions about who you are, and to have opinions about what you do. What has it meant to you, to have to balance personal ambition against all manner of public perception and scrutiny?

When I first played for audiences that were large enough for me to get a sense of possibly having some longevity in the pursuit of my artistic interests, what I was immediately aware of was the question of what to do with that kind of opportunity. What does one do with the power of public loyalty, and what is your responsibility to it? And in the wake of those questions, I remembered Paul Robeson saying to me early on, “Get them to sing your song, and they’ll want to know who you are.” And I realised one might be able to inspire people. And if I could, then I could give validity to causes in which I truly believed. Never in my wildest dreams did I imagine standing in front of, say, 50,000 Japanese people singing “Day-O” back to me. But it was much deeper than just having a hit record and then cranking out another – which was the thinking of the commercial machine at the time. It was about communion. My point being that I never allowed myself to view my personal artistry as separate from my social responsibilities.

Dylan pulled a harmonica out of the bag, dipped it in water and played through a single take. Then he headed for the door.

Folk music derives much of its power from its grassroots authenticity. Was it difficult to articulate that to a mass, mainstream audience when you began? How much of the process involved adapting the music for them, and how much of it was just teaching a broader audience how to hear it?

I’ll tell you, the audiences were the least of my problems. The real problems for me existed among the practitioners of the art. They were such purists, and there was not a lot of generosity out here for anybody if you didn’t come down a dusty road with a banjo over your shoulder, a piece of hay stuck between your teeth, and a plaid work shirt. The way I chose to interpret a lot of those songs was aimed at an audience I felt was being completely overlooked. I took a lot of the great folk songs and I gave them certain dramatic twists and turns, which was the privilege of the folk artist as I understood it. But the purists never saw it as a privilege granted to someone they regarded as coming from outside their community. I don’t retell this any longer to batter Joan Baez – my love and respect for her is immense, you need to understand – but in her first big interview, when she was on the cover of Time magazine [in 1962], she referred to me as “Harry Bela-phony.” That really cut me deeply, and I realised how narrow these people truly were, and how difficult it was to gain any approval from them if you weren’t presenting yourself as they sanctioned you to appear.

In the same way, when Bob Dylan really found his very singular voice as a writer, the folk community branded him a traitor to their cause, because he was basically saying “I am not working for a cause, I am writing these songs for myself.”

Yeah, and I am singing the songs that I need to sing, and for the audience that has a passion to hear them. I recorded many songs in my day that were being interpreted by others, and there were times when I ran farther ahead with the versions I sang than even the artists who had originated them. And rather than looking at this as a wonderful testament to the power of their song, I was treated as though I were somehow stealing their platform. Even when the text of those songs was addressing our unity, our common humanity! The folk artists of the era weren’t quite so generous with their territory as their songs suggested.

In the beginning, you had no aspirations for becoming a singer at all, but had studied seriously to be an actor. How do you think your drama training prepared you for a life in music?

It not only prepared me, but instructed me all along the way. It never left me. When I looked at a song, I saw beyond the structure of it and tried to see deeply into the nuances of the text… asking, if I change a word or phrase here or there, might I shift the song in some meaningful way? Like any actor does when creating a character from dialogue.

Well, given that you began as an actor and was a reluctant singer on-stage, when did you develop your very distinctive style as a singer? I mean, your earliest recordings evidence a fully formed, very stylised musician at work, so when did that happen?

Unbeknownst to me, it really happened the first times I stood on-stage singing the Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly songs I was asked to sing in a play called Of Mice And Men, in a production at The New School For Social Research. When the director decided to use a balladeer to sing and reflect the changing moods of the play, to fill in while sets were being changed, he spent as much time with me working on the delivery of the songs as he did with the other actors, to make sure the nuance of the songs was fulfilled by the character that I was as I sang them. So it all came out of an acting perspective.

And when later I found that my livelihood depended on singing, I struggled with the identity. I was extremely uncomfortable trying to be another Billy Eckstine. I mean, those clothes just didn’t fit me. I was ill-placed. Then I stumbled into the Village Vanguard and saw Leadbelly perform and thought, Oh my God, here it all is. And then I went down to the Library Of Congress and dug out all those old chain-gang things, and learned all those great songs that John and Alan Lomax had recorded, and I just sang these songs the best I could. I was hungry for them.

But I decided early on not to let my repertoire be so limited, because it wasn’t just about folk music. I sang the songs of the Caribbean, I sang the songs of the musical theatre, of the Jew, of the Spaniard, and the Greek. And I went to those audiences and sang their songs to them in their tongue, and in ways that not only pleased them, but in ways they found quite revealing – about who I was, and who they were.

Did you at some point stop seeing distinctions between musical genres altogether?

Absolutely. Again, it was all theatrical text, in a way, and I was an actor giving voice to it.

Your seminal live album Belafonte At Carnegie Hall from 1959 – the first stereo live recording ever released, we should note – was a benefit performance done on behalf of Eleanor Roosevelt for The Wiltwyck School [for emotionally disturbed boys], and she was present.

You opened with a version of the folk song Darlin’ Cora, which is sung from the point of view of a slave on the run for having beaten down his master. The song contains the lines, “I beat that man, Darlin’ Cora/and he fell down where he stood/don’t know if it was wrong, Darlin’ Cora/but Lord it sure felt good.” How conscious were you, being a black performer in the earliest days of the civil rights movement, on that particular stage, and in front of that audience, of what it meant to sing out those words?

Oh, very conscious. Fully. I started the evening that way very deliberately, because I didn’t have that much time for the audience to discover my purpose on that stage. I began with my purpose. You must remember that my mentor was Paul Robeson. And we all, every time we stepped on a stage in that day, did so thinking it might be our last opportunity. The fates were kind to me – it wasn’t my last opportunity. But I approached it as if it were.

Dr King called you into his service, and your friendship with him became and remains one of the most meaningful of your life. How did you meet?

He called me and introduced himself over the phone. He said, “You don’t know me, we’ve never met, but my name is Martin Luther King, Jr.” And… I was waiting for the joke, because everybody knew who he was. But it wasn’t a joke. He said, “I am calling you because I think you might be of service to something I very much believe in.”

I went to see him speak at a church in Harlem. Afterwards we adjourned to the basement and sat at a little card table where the ladies used to play bingo, and he told me his mission. We talked for… well, it was supposed to be 30 minutes but it turned into nearly five hours. He would not release me and… I would not be released.

Malcolm X, who I learned about, read, and revered before really coming to Dr King as any kind of student, was always held up in the mainstream press of the day as Martin’s polar opposite. Yet the hindsight of history reveals how closely linked were their pursuits and focus. Were you aware at the time of how they might be influencing each other’s thinking and activities? Did Martin ever talk to you about Malcolm?

Oh, we spoke of Malcolm all the time. He and Martin had a tremendous respect for each other. Martin loved Malcolm’s power, his discipline, his self-education, his clarity. Martin said, “Only one thing stands between us. One issue, one word: violence.”

And of course, when Malcolm came back from Mecca and professed a new philosophy – that there was no such thing as ‘race’, that white was a state of mind – when he stood ready to embrace the one power most intolerable to his adversaries – that being non-violence – well, then his demise was assured.

I appreciate you illuminating some of that. I am always troubled by the lingering suggestion that Martin and Malcolm were adversaries. Can we talk a bit more about your musical history… Bob Dylan made his official recording debut in 1962 on the title song of your album Midnight Special, playing harmonica. How did that come about?

It was supposed to be Sonny Terry, but he got grounded by a thunderstorm in Memphis and couldn’t make the date. My guitarist Millard Thomas said, “Well, there’s this kid I see all the time down in the village, and he does that whole Sonny thing… he sleeps and dreams it.” So I said, “We don’t have a choice, I guess. Go find him.”

And this skinny kid appeared, and he had a paper sack with him full of harmonicas in different keys. I played the song for him and he pulled one out of the bag, dipped it in water, and played through a single take, and it was great. I loved it. I asked him if he wanted to try another take and he said, “No.” I asked him if he wanted to hear it back and he said, “No.” He just headed for the door, and threw the harmonica into the trashcan on his way out.

I remember thinking, Does he have that much disdain for what I’m doing? But I found out later that he bought his harps at the Woolworth drugstore. They were cheap ones, and once he’d gotten them wet and really played through them as hard as he did, they were finished. It wasn’t until decades later, when he wrote his book [Chronicles], that I read what he really felt about me, and I tell you, I got very, very choked up. I had admired him all along, and no matter what he did or said, I was just a stone, stone fan.

Speaking of the diversity of music you admire, you have been interested in rap and hip hop music from its inception, and you’ve talked to me quite a bit these past months about your disappointment with how the culture and the message have been co-opted. Can the empowering aspect and the language of that music be reclaimed?

Not only can it be reclaimed, but it can become the vanguard of a 21st-century statement. I think the world needs to hear the deeper heartbeat of that culture. No art has emerged from black life that has the capacity and power to reflect what we think, what we feel, and what we aspire to, as does the music that comes from the hip hop genre. That’s how it started out. But as soon as the merchants found commercial value in it, they stepped in and destroyed the harvest altogether. And the artists let it happen.

To touch on your current work, you are just finishing a film documentary about your life, and also you are writing a memoir. Have you had to shift your thinking at all, being someone with so much new work before you, but asking yourself to look back so intensely?

The two ideas are not in conflict with each other. So much that I have been forced to recall in the process has propelled me toward a lot of new thinking.

Makes sense to me, since all the great minds invariably regard the past, present and future as all keeping company in the same room together.

Oh God, yes.

One of your last leading film roles was as an underworld kingpin in Robert Altman’s Kansas City. How did people react to their Prince Harry playing such a nasty motherfucker?

(Laughing) Oh, they were absolutely shocked. But fortunately, people got caught up in the character and were distracted from my social persona.

For some reason, we can all accept actors disappearing into characters, but the public is frequently seduced into thinking singers are representing their true selves in song.

Well, as we discussed earlier, I’ve always sang to represent a character in a moment.

You recently turned 83, and yet it doesn’t seem as though you harbour many retirement fantasies.

(Laughing) I have them every day!

And yet?

It’s the demons that won’t let me go!

This article originally appeared in MOJO 200