The first in Dylan’s trilogy of mid-’60s ‘electric’ albums, Bringing It All Back Home saw his wordplay reach dazzling new heights and his songs combine The Beatles, the Beat Poets and raw blues to seismic effect. On the anniversary of its release, MOJO’s Mat Snow revisits the album that would change everything for Dylan, and the world.

SO hallowed in the pantheon is the first of what turned out to be Dylan’s mid-’60s holy trinity of ‘electric’ albums that hindsight confers upon it a sense of awesome inevitability. At the time, of course, not so.

Though Dylan’s two 1964 albums had not sold quite as well as 1963’s The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, that year he was spinning in a vortex of fame whipped even faster by his association with the British Invasion. In August, he’d turned The Beatles onto weed in a New York hotel room – while The Animals, whose House Of The Rising Sun was a US Number 1 in September, both nodded to Dylan’s 1962 debut album version and rocked it up a few notches. This mutual admiration further inflamed the controversy surrounding Dylan as a folk-protest apostate, forsaking civil rights and peace for creative self-exploration and supercool celebrity. No American musician was more divisive.

READ MORE: Bob Dylan In The 60s, All The Albums Ranked

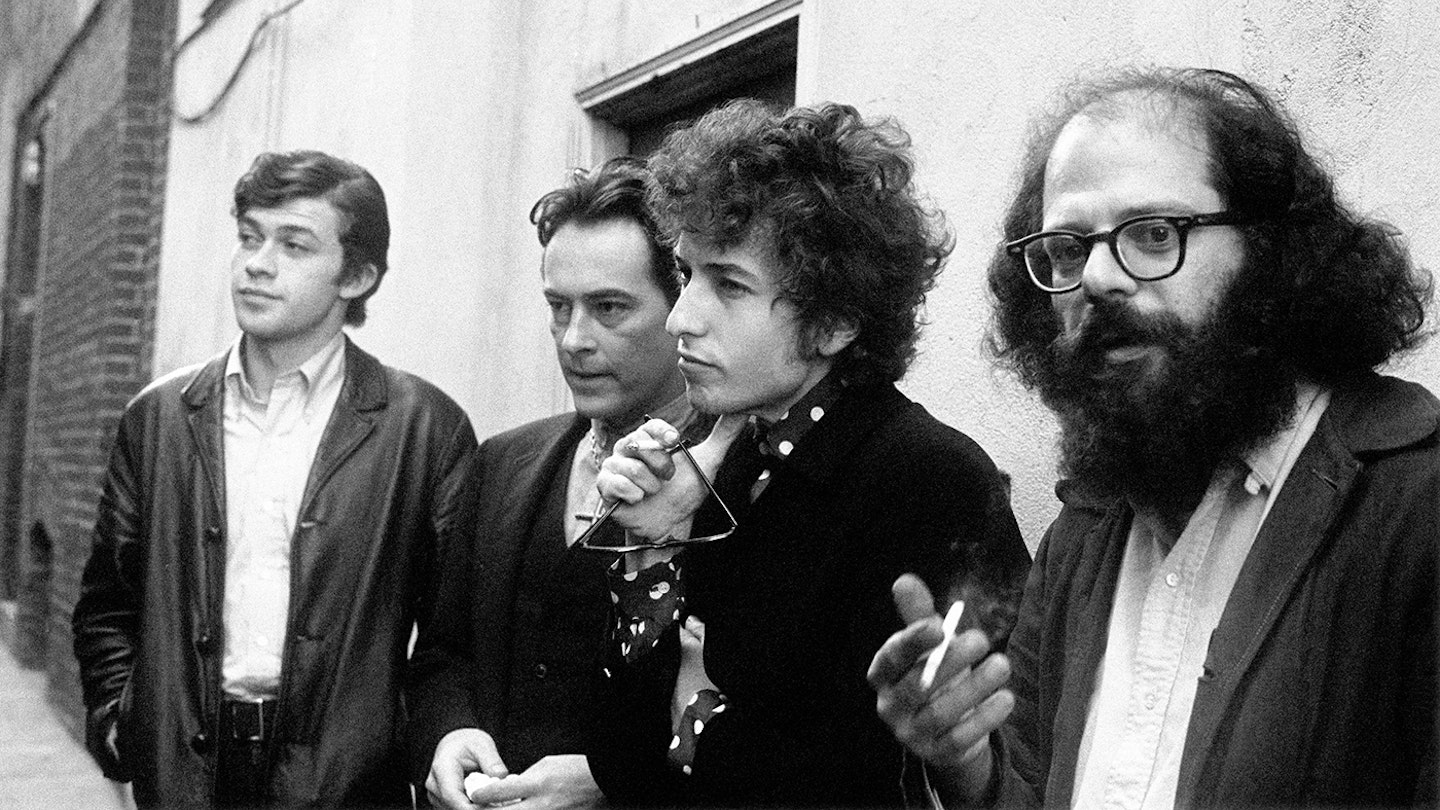

His folk-protest movement detractors were not wrong. No roundhead, Dylan was a footloose 23-year-old surrounded by acolytes and juggling girlfriends – publicly folk-protest queen Joan Baez and behind the scenes Sara Lownds, whom he’d marry in November 1965. Plus, there was a flirty friendship with his manager Albert Grossman’s wife Sally, to be pictured chic and mysterious on Bringing It All Back Home’s cover. Dylan was also hanging out with Allen Ginsberg and his fellow Beats [pictured above with Robbie Robertson and Michael McClure], his own poetic ambition further fired when John Lennon’s book of verse, In His Own Write, became an instant bestseller.

On January 13, 1965, Dylan returned to New York’s Columbia Studios with 18 songs written from within the whirlwind, energised by media overload and lubricated by red wine, weed, speed and acid, then still legal. What would become perhaps his most famous and beloved song, Mr Tambourine Man, had been awaiting its moment for 10 months. That moment was, for Dylan, the decision to change gears and light out for new territory. Here and throughout the album, images of movement (“swirling”, “wandering”, “dancing”, “spinning”, “swinging”, “skipping”, “waving”) contrast favourably with images of stasis (“weariness”, “fences”, “frozen”, “haunted”).

That personal moment exactly harmonised with a socio-cultural moment, a radical new mood being born where a critical mass of young Americans – now facing the draft to fight in Vietnam, while at home Southern reactionaries fought on to deny Black Americans equal rights – began to challenge the status quo of their parents’ flag-waving conservativism and materialism. As Dylan sang on Subterranean Homesick Blues, the album’s hilariously paranoid single and opening number inspired by Chuck Berry’s Too Much Monkey Business and foreshadowing rap, “You don’t need a weatherman/To know which way the wind blows.”

Rock’n’roll, as radically rebooted by the British Invasion and soul explosion, soundtracked this generational change in appearance, lifestyle and attitude. Though the just-murdered Sam Cooke’s A Change Is Gonna Come and Martha And The Vandellas’ Dancing In The Street came close, no record had quite yet crystallised this moment as a clarion call; it just needed someone to hit the nail head-on.

For months his shrewd and savvy producer Tom Wilson had been coaxing Dylan to rock – with “some background,” he told Grossman, “you might have a white Ray Charles with a message” – and that summer of ’64 the bard had rented an electric guitar, as if still not quite yet decided to relive his teenage ambition to rock’n’roll. His friend John Hammond Jr’s album of Chicago electric blues covers So Many Roads nudged him further, and the leap finally came, after a day recording solo in Columbia’s New York Studios in January 1965, when Wilson recruits including guitarist Bruce Langhorne, pianist Paul Griffin and drummer Bobby Gregg – possessing, in Wilson’s words, “the skill of session musicians and the outlook of young rock’n’rollers” – set up and plugged in.

READ MORE: Bob Dylan's Blood On The Tracks Revisited

“Bob would launch into a song. No warning, no explanation, no nothing. We’d just leap in and try to keep up,” Langhorne remembered. “He didn’t try to arrange people’s performances. It was spontaneous, almost telepathic. We had to catch the moment.”

It worked, the moment often caught on the first take, and even the solo acoustic songs bunched on Side 2 ring with fierce conviction, particularly It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding), machine-gunning us with a critique of societal phoniness of such epigrammatic invention and intensity that its writer counts it among his supreme tours de force.

Elsewhere the songs are comic, romantic and, in the last song It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue, anti-romantic, its prettily bittersweet melody and manifest influence of such French Symbolist poets as Rimbaud and Verlaine perfuming a conclusive dumping.

Side 1 hosts the romances – She Belongs To Me, Love Minus Zero/No Limit (a cryptic conceit in the form of a mathematical equation where ‘no limit’ is ∞) – and, in addition to Subterranean Homesick Blues, the comedies Maggie’s Farm, Outlaw Blues, On The Road Again and Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream, picaresques that tumble our jester-minstrel through the preposterous grotesqueries of exploitative dead-end jobs, in-laws and, finally, mythic America itself.

In even the least quotable song, Outlaw Blues – the beautiful I’ll Keep It With Mine was one of several better songs he decided to hold back “for next time”, as Dylan told photographer Daniel Kramer, worrying, “How do I know I can do it again?” – there are ringing lines, and the whole album boasts zingers still funny after six decades and verse upon verse of poetic resonance and beauty; there can be few more gem-encrusted artefacts in the English language since Shakespeare. Plus, it rocks. Finding its moment, Bringing It All Back Home was not just a must-hear hit but an utter game-changer.

Picture: Dale Smith / Alamy Stock Photo