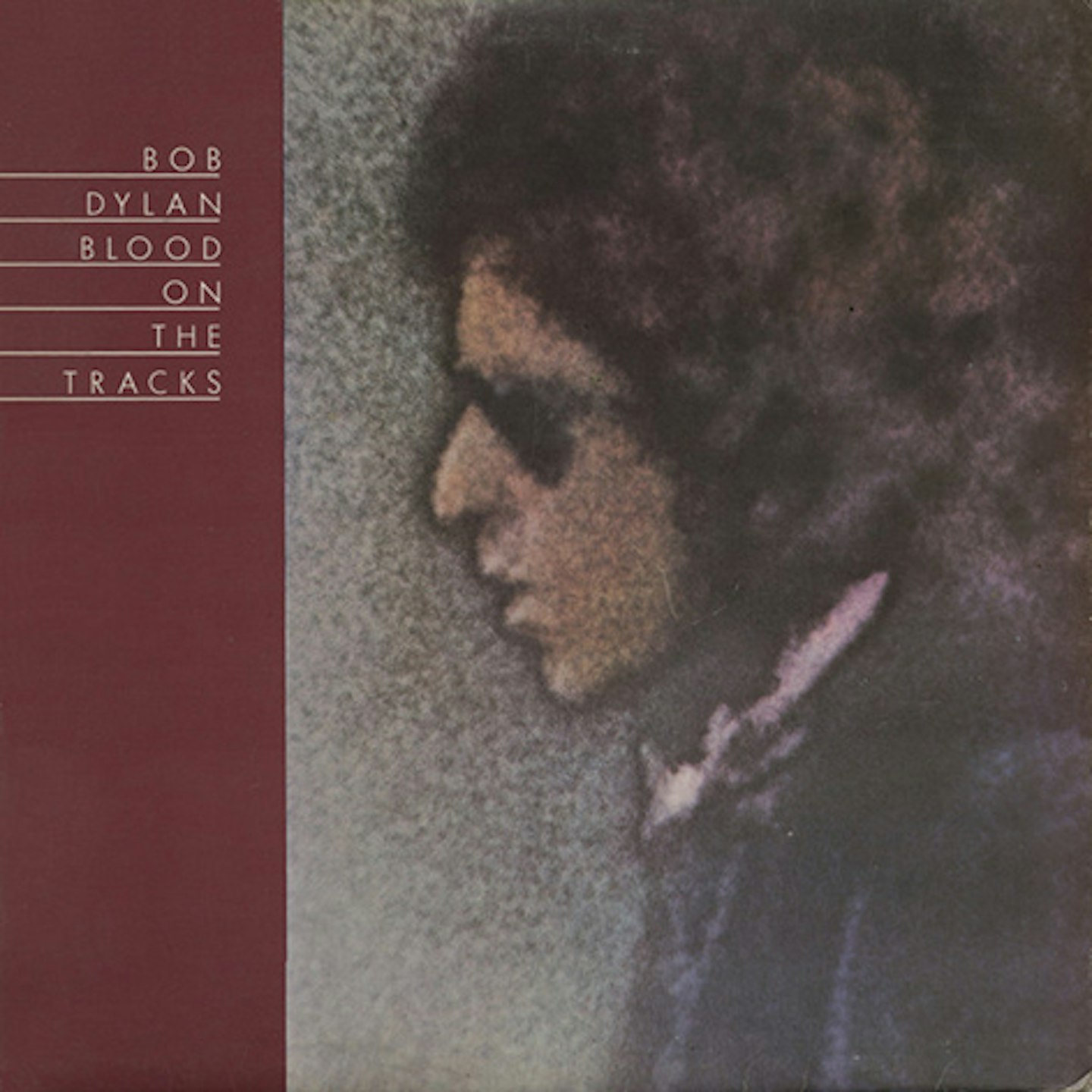

A decade on from Blonde On Blonde, Bob Dylan made another timeless artistic statement, spurred by the agony of a disintegrating marriage. Or was he just reading Chekov? 50 years on from its release, MOJO’s Victoria Segal traces the anatomy his 1970s masterpiece, Blood On The Tracks…

-

READ MORE: Bob Dylan's 60 Greatest Songs, as chosen by Paul McCartney, Nick Cave, Patti Smith, Bono and more...

Eric Weissman was bewildered. It was September 16, 1974, and the guitarist in ace session band Deliverance had found himself in an unexpected situation after encountering engineer Phil Ramone outside New York’s A&R Recording Studios. Bob Dylan was coming down to start recording his 15th album but with no band booked, could Weissman and his colleagues step in? It was a wild hand to be dealt – wild, bordering on the impossible. As the sessions swept onward in a wave of new songs, “Dylan couldn’t have cared less about the sound of what we had just done,” Weissman recalled. “We were totally confused because he was trying to teach us a new song with another one playing in the background. I was thinking to myself, Just remember, Eric, this guy’s a genius. Maybe this is the way geniuses operate.”

Deliverance lasted two days in the studio (though Dylan would hang on to bassist Tony Brown). Weissman’s instincts were right, however: Blood On The Tracks very much feels like the way geniuses operate. Within three verses of opening track Tangled Up In Blue, Dylan has hit every point on the geographical compass – “Heading out for the East Coast” to pay his dues; abandoning a car out West; “working as a cook for a spell” in the Great North Woods; finding employment on a fishing boat “right outside of Delacroix”. Yet he’s also striking out for a pole-to-pole trip through love and its emotional stations: fury, joy, despair, beauty.

Tangled Up In Blue’s pile-up of different lives suggests he’s unhooked from the constraints of time and space, the starting place for a record that has no fixed point except Dylan, the world’s least reliable narrator. “All the people we used to know/They’re an illusion to me now,” he sings, dismissing those who belong to a world of straight lines and Newtonian laws, the “mathematicians”, the “carpenters’ wives”. Instead, he’s “still on the road/Heading for another joint”, still seeking, still rolling. How does it feel? On Blood On The Tracks, the answer is clear. Not good at all.

Born from the strife of his disintegrating marriage to Sara Lownds – or, if you choose to believe the memoirist Dylan of Chronicles Volume One, his reading of Chekhov short stories – Blood On The Tracks is full of pain so deep Dylan later declared himself mystified that anyone could enjoy these songs. If the delirium of classically dictated romance is extolled in Tangled Up In Blue’s “book of poems… written by an Italian poet from the 13th century”, by the spectacular gothic spite of Idiot Wind love has gone entirely off-script, its source material toxic: “I can’t even touch the books you’ve read,” he spits. This is his own origin story, full of tarot-card archetypes and wood-carved tableaux. It’s one of one-eyed undertakers and hanging judges, howling beasts and new-born babies. One of Lily, Rosemary And The Jack Of Hearts, playing out their folkloric fates as Dylan moves them about like shadow puppets. One where, as on the Love Minus Zero/No Limit lilt of Shelter From The Storm, he was “a creature void of form” before a woman offered him a home. As Ramone recalled, when he witnessed the first sessions for Blood On The Tracks – later usurped by re-recordings in Minnesota with Dylan’s brother David Zimmerman – he saw “a soul being revealed directly to tape”.

In 1974, Dylan was once again out to paint his masterpiece, and not just because he was looking back to his looming ’60s peaks, picking up the cosmic threads of Blonde On Blonde and Highway 61 Revisited. Moving on from the derided cover of 1970’s Self Portrait, he had taken a class with the artist Norman Raeben, a decision that would lead to one of the most dramatic “my wife doesn’t understand me” excuses ever. There were, inevitably, other reasons for the disintegration of his marriage – strife over their home-building project in Malibu, the infidelity that informs the false-dawn euphoria of You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go – but Raeben’s radical vision would shake the scales from Dylan’s eyes. “I learned to see things from multiple angles,” he said in 1978. “I went home after that and my wife never did understand me ever since that day… She never knew what I was talking about, what I was thinking about. And I couldn’t possibly explain it.”

Being understood wasn’t everything, though. Dylan embedded a warning to listeners in Idiot Wind: “People see me all the time/And they just can’t remember how to act,” he sings, still burned by the white-hot attention of his voice-of-a-generation pomp. “Their minds are filled with big ideas/Images and distorted facts.” Blood On The Tracks demands those big ideas – how else to approach Simple Twist Of Fate reanimating ancient ideas of soulmates and destiny, the woman dropping “a coin into the cup/Of a blind man at the gate” to activate another cycle of love and loss in an uncanny, purgatorial landscape of hotels and bedrooms? The intimate lullaby of Buckets Of Rain, meanwhile, switches to gentle In-The-Summertime comedy to capture the innate flaws of the human heart: “Like your smile/And your fingertips/Like the way that you move your lips/I like the cool way you look at me,” sings Dylan, before scything, “Everything about you is bringing me misery.”

Yet it’s the pleading You’re A Big Girl Now where nerves run closest to the surface, everything coming down to a pain “like a corkscrew in my heart”, a bird on a fence “singin’ just for you”. All those mysteries, boiling down to this. “It doesn’t stop. It wouldn’t stop. Where do you end?” said Dylan of Idiot Wind’s self-perpetuating rage, but he could have been talking about Blood On The Tracks as whole. “You could still be writing it, really. It’s something that could be a work continually in progress.

This article originally featured in MOJO The Collectors’ Series: Bob Dylan Essentials, the definitive guide to Bob Dylan’s albums, songs, films and books. More information and to order a copy HERE.