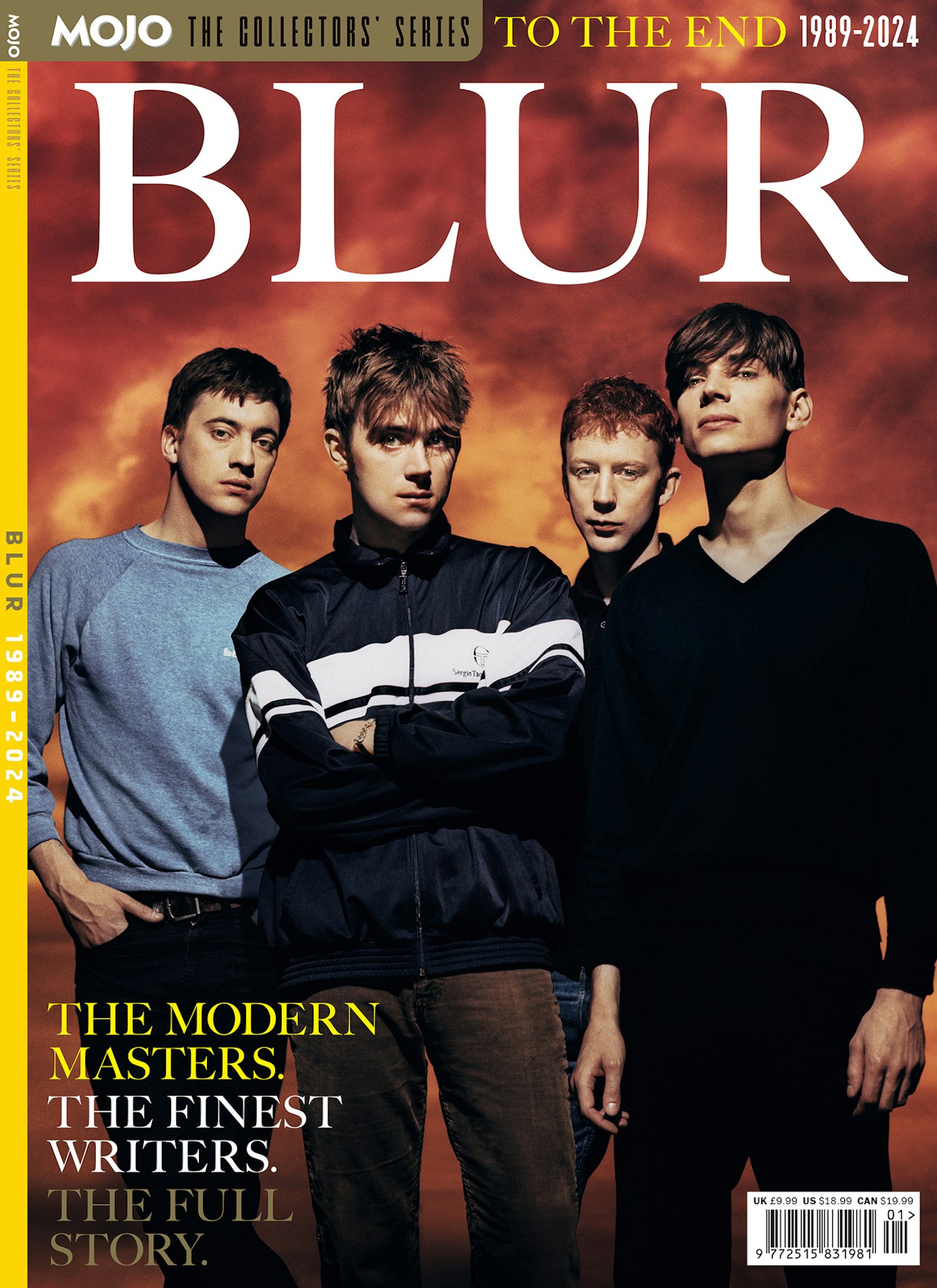

Photo: Kevin Westenberg

On April 25, 1994, Blur cemented their reputation as Britain’s most important group with their third album Parklife, a record that celebrated and satirised British life with a soundtrack that veered from Euro-pop, musical hall and John Barry to punk and classic songsmithery. MOJO’s review by the legendary music writer David Cavanagh looked back at just how Blur arrived there…

Damon Albarn in 1990: “When our third album comes out, our position as the quintessential English band of the ’90s will be assured. That is a simple statement of fact.”

Dragoon of flustered journalists: “Fine. One thing, though. Where is this album?”

Albarn: “I intend to write it in 1994.”

Parklife, Blur’s new album, is a triumph of arrogance over common sense. These boys are every bit as confident as the music suggests. Utterly convinced of their own importance, scathing of American rock and all its scaley talons, they have out-Davies’d the immortal Ray himself with this hugely satisfying, uniquely diverse, courageously tragicomic snapshot of buggered old England’s bank holidays, family units, lager hangovers, Quadrophenia and bloody awful weather. Bingo! Yer Blur classic.

-

READ MORE: Every Blur Album Ranked

When I first met them, which would have been January 1990, their singer Damon Albarn, whom I didn’t much like, had this peculiar interview technique of making as many extravagant predictions in Blur’s favour as possible, while giving no details away whatsoever. At something like their seventh ever gig he was comparing them seriously to The Beatles, announcing that he was “really looking forward to our Sgt. Pepper phase”.

Andy Ross, the man who signed them to Food Records and changed their name to Blur from Seymour, insisted they were all genius classical musicians, or some of them anyway, and Damon was in time going to redefine the very essence of the term ‘pop star’. Damon promptly refused to talk about Seymour, or being classically trained. “We are as good as The Who, though,” he said helpfully.

Influences were hard to pinpoint that night at the Camden Falcon as Blur tore through their set and Damon boinged around. One night soon he was to make himself so dizzy he was sick. On-stage. Also, considering how great he thought he was, Damon’s lyrics were festeringly self-abusive, moribund and tongue-tied. He drooled to unattainable women: “I love her/She doesn’t care if I live or die/And that is why/I love her.” It was a hymn to the pathetic.

They were really good, though. Graham Coxon was obviously a demon guitarist, even if he just rubbed his eyes angrily every time you tried to talk to him. They got immediate, good press, but still they made all these reckless guarantees – delivered as solemn assurances in their classless, almost-but-not-quite-Cockney accents. It was the first sign of Albarn’s magnificent Method Boasting, the Caesarean hard sell, everything premature. Even in pop music, arrogance is somehow deemed more seemly when it comes from the truly successful, which, of course, he wasn’t.

They had, yes, been called Seymour for a while. Seymour was supposed to be a person: disreputable, uncool, a bit mad. Their best tune was The Opening: indie band challenges Brecht over a spilt pint; good kicking results. It turned up on Blur’s second album, re-titled Intermission.

Before that, Damon and Graham had been friends in Colchester since about 12, antagonising teachers with their pitying stares and unshakeable self-belief, getting fired up to the point of apoplexy by Morrissey’s quote in The South Bank Show special about pop music being over because The Smiths were over. That year, 1987, Damon was one half of a synth duo called Two’s A Crowd. Photos show him heavily made up, trying much too hard. “That is the only thing I’m really too embarrassed to talk about,” he admits now.

We met next in April 1991. Blur were edgy. By now they’d had their big hit, There’s No Other Way. It was a homecoming gig, of sorts, at the University just outside Colchester. Damon was worried about being beaten up as he’d left the town in one of his not-if-I-see-you-first moods. It went brilliantly. I couldn’t believe Alex James could play bass so well, so drunk. Their parents came, including Keith Albarn, Damon’s father, mentioned in Michael King’s book on Robert Wyatt, Wrong Movements: in the summer of 1967 he built a discotheque for them to play in on Saint-Aygulf beach in the South of France.

In the spring of 1991, Blur were talking about Englishness a lot, although it seemed to revolve around a specifically suburban, affluent, dull, complacent, car-washing, Oxo-family state of mind, which they found intriguing. They made big claims to anyone who listened. Suede were not yet well-known, but one night Damon introduced me to his girlfriend Justine, who was then Suede’s rhythm guitarist.

Summer 1991 came and now Damon was unstoppable: “We are a band who could completely and utterly change everything.” The Leisure album was about to come out, with its dancey pop sound and groovy bass playing. They roared with laughter as they watched themselves on Top Of The Pops in EMI’s office.

By now, you were either totally on Blur’s side or totally contemptuous. I was totally for them. Nowadays, it’s hard to get anyone to say a good word for Blur’s music in 1991 – too ironically baggy, too tight-arsed, too samey. But we have to salute the six-minute Sing, plus Graham and Damon’s cherub harmonies on Birthday.

In 1992 it was, “Oh, they’re too self-conscious and, er, where were the much-promised hit singles?” They became dispirited, drunken and ill. If they’d had more money one of them might have died. When their film Starshaped came out, their ex-manager had his eyes obscured by a black strip that moved when he did, international terrorist style.

Musically, they started to really impress, but it was mostly on B-sides, where you could find the impressive, Syd Barrett-inspired Badgeman Brown or the fabulous instrumental Garden Central. They kept this up well into ’93: fantastic songs like Young And Lovely, Beachcoma and Es Schmecht (German for “it tastes good”, slightly misspelt), just thrown away. Or When The Cows Come Home, Ray Davies wistfulness meeting a distressed oompah band, with whistling. They’d all be on the tape. “Oh, we’ll release an album’s worth some day,” Damon shrugged. “Eat up our option.”

Ray Davies was the new fetish. Cheesed off with America on their second US tour, Damon re-played Waterloo Sunset in each hotel room and wrote songs about England, most of them scathing, and wrapped them all up in an old Art slogan, Modern Life Is Rubbish. It was pop music about trash culture and Blur now had a terrific album.

Alex writes a song every two years and they’re all about planets.

Damon Albarn

It went through shaky times. First, Andy Partridge was going to produce it, then he wasn’t. A pity. XTC’s wondrous Skylarking album (1986) was like a less acidic version of what Blur did on Modern Life. Then Storm Thorgerson, who told them they had the spirit of early Pink Floyd (big compliment, went down very well), was going to do a film with them, but didn’t. They played The Jesus And Mary Chain’s Rollercoaster tour, flinching as their ace single Popscene quietly stiffed. What a chorus, though. “Hey hey, come out tonight/Popscene!/Alright.”

Everyone liked Modern Life. The days of the anti-lyric had gone. Damon began Chemical World, about a shop assistant who tires of London, with the extraordinarily fast line “the pay-me girl has had enough of the bleeps”. Sarcastically, they included all the chords of the songs on the lyric sheet. Now it was safe to admit they could all play. Damon, a classically trained pianist, had written for orchestras in his teens, winning his regional heat of Young Composer Of The Year. Coxon, who played guitar brilliantly, as well as saxophone and drums, was in point of fact a pocket jazz trio. Alex, ever more conversational as the months unfolded, upgraded to showcase bass and said things like “England’s all right, y’know? We discovered light-emitting plastics”. Dave is 100 per cent.

One of the many delights of Parklife is Alex’s song Far Out, son of Astronomy Domine, a proud, weird way of saying that Blur are not just about London. “Alex writes a song every two years and they’re all about planets,” sighs Damon. But moods change violently on Parklife. For two minutes the album is spacey and distant, then it swerves into John Barry swishiness on the luscious ballad To The End. You get Mod rock, thrilling harmonies, ingenious pop, that dreadful single Girls & Boys (but thank God it was a hit) and the actor Phil Daniels doing a righteous Cockney on the title track. The words are Damon’s: “I feed the pigeons… I sometimes feed the sparrows too… it gives me a sense of enormous well-being.”

Years ago, when albums were this funny and magical they had titles like Something Else By The Kinks and the Small Faces’ Autumn Stone. Blur are that good now.

This article appears in Blur: To The End 1989/2024. More info and to order a copy HERE.