In 2004, 17 years after The Smiths spilt up, MOJO’s Paul Stokes met Andy Rourke in a Manchester bar to discuss the highs and lows of The Smiths’ career and its troubled aftermath. In memory of Rourke, who passed away in 2023 following a battle with pancreatic cancer, here is an extended version of the interview in which he talks about first meeting Johnny Marr at school, his brief expulsion from the band, working with Morrissey, the infamous court case and more…

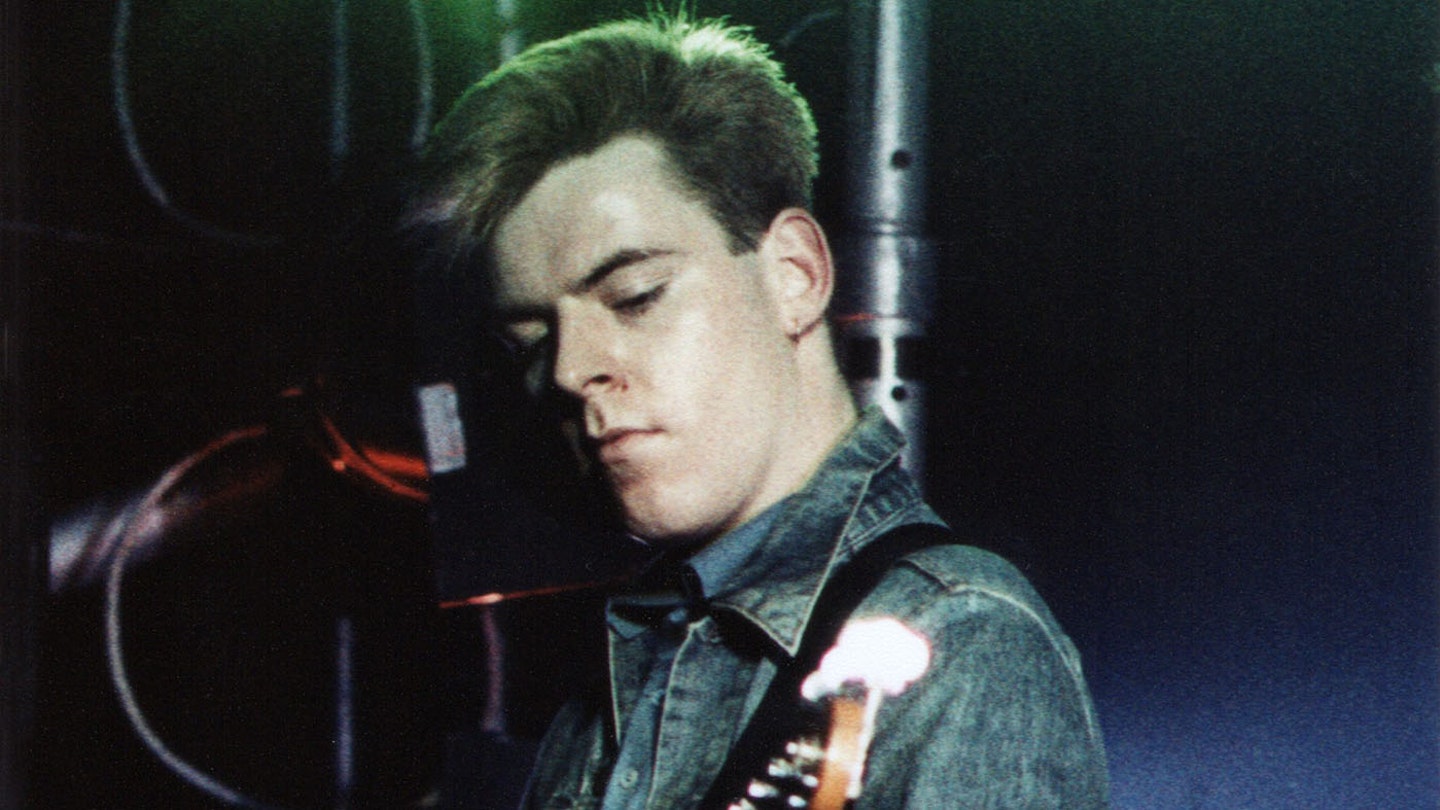

Picture: Getty/Pete Still

You and Johnny Marr knew each other the longest of all The Smiths. You met at school?

We went to St Augustine’s secondary school. Johnny was in the same year but a different class. I was in the bad boys’ class and was getting a bit out of hand, so the headmaster thought if he put me in Johnny’s class, which was the well-behaved class, that might pull me in line. Johnny and I got chatting because one of us was wearing a Neil Young badge, so we brought in our guitars and started jamming to Young and Springsteen songs together. I’d had classical lessons when I was eight, so for a brief moment in history I was a better guitarist then Johnny. But once he hit 13 he was away, there was no stopping him. He was like a racehorse.

So you switched to bass?

I started playing bass because of Curly Watts, of Coronation Street. Kevin Kenne-dy, the actor who played him, was in a band with me, Johnny and a guy called Bobby Durkin on drums. All Kevin could play on bass was Thin Lizzy’s Don’t Believe A Word. After 17 rehearsals it was wearing a bit thin, so one night I said, “Let me have a go.” I just got really into it. I started listen-ing to Stanley Clarke and, dare I say, Level 42 – though not for very long. I was just pushing the boundaries, seeing where I could take it.

Is that why you didn’t join The Smiths initially, despite being in bands with Johnny before?

We were in a band called The White Dice for a bit and did some recording, but then I got more into some other things. After a while I realised I didn’t want to be in a funk band, so I pulled back from that, it was around that time Johnny approached Mor-rissey to do some songwriting. They did a gig with another bass player called Dale, who wasn’t great, so they got me in for the next session. That was the first time I met Mike, but it all clicked. Literally six months later we were on Top Of The Pops.

What were your first impressions of Morrissey?

He was just a very private person. We used to rehearse at Joe Moss’s clothes shop Crazy Face, and Morrissey lived on my bus route home, so we got the bus together. He got off at Stretford, I got off at Sale. I sat on the bus with him for 20 minutes every night. It was always a struggle for both of us to find things to say. Invariably I’d talk rubbish just to make him laugh. He was a very hard nut to crack.

So you remained closer to Marr?

At least I knew somebody. Me and Mike hardly spoke for the first year, not until we went on tour. Mike and I would end up sharing a room, so that’s probably the only reason we got to know each other. I don’t think Mike even liked me as a person for the first year, but once we got to know each other we got on famously.

How did The Smiths’ rhythm section develop so uniquely if you weren’t speaking?

Maybe that’s why it developed. I had some-thing to prove to Mike and he had some-thing to prove back. It created quite a dynamic but aggressive sound. Even on the quiet ones there’s some kind of angst there between us, so not talking much probably helped us. There was nothing contrived about it. We were duelling off each other.

How close did you all eventually become?

We were a gang. A very tight band of brothers. When we were at our peak nobody could penetrate that, we were united in what we were doing. I think that got us through the pressures of getting famous, management, record companies. We were always tight and nobody could chip away at that.

Who was the gang’s leader?

Inevitably the singer is going to get talked about, but we didn’t mind because Morrissey was The Smiths’ mouthpiece. Maybe I didn’t agree with all the stuff Morrissey was on about, but I wasn’t going to say that at the time because we had to put on a united front.

What upset you in particular?

It was just stuff I was uneasy about. It sounds ridiculous now, but the cover of our first single, Hand In Glove, it’s a naked guy with his arse showing. I remember buzzing, thinking I’ll take this home and show my dad, then realising he’ll be, “What the fuck is that?” And some of lyrical content as well. I was fine with it, it was more my family I was concerned for.

To the outside world The Smiths were very clean-living, but inside we all liked to experiment, shall we say… I just happened to get caught.

But despite your reservations you kept quiet to keep Morrissey happy?

It was never a matter of keeping Morrissey happy. The only things I had problems about was my immediate family, because I knew they wouldn’t be able to understand it. But the way Morrissey writes is genius. It would be like telling Oscar Wilde, “Oh I’m not sure about that” – you just don’t do it.

It seems your relationship with Morrissey really developed from those bus rides.

We just hit a groove where I would be the court jester. I’d just make him laugh and he’d turn me onto books, play me tunes on his Walkman. We were together five years, and I doubt whether we had a deep con-versation about anything, but we’d mastered the art of chit-chat.

You ended up writing with him at the beginning of his solo career?

I did Yes, I Am Blind and Girl Least Likely To, among others. I’m really proud of Yes, I Am Blind, I think he’s been playing it live. I suppose I stayed with him the longest out of all The Smiths because we both dug what we did. I thought he was an amazing lyricist and I think he dug my bass playing, but it didn’t go much further than that.

How did you cope in 1986 when you were briefly kicked out of the band because of your heroin problems?

I was devastated. I remember going round to Johnny’s in tears, going, “What the fuck am I going to do?” Luckily, I was out of The Smiths for about two weeks, and during that time The Smiths didn’t actually do anything. It was a wake-up call for me to get my head together, my last chance. At the time, though, it was probably the most horrible moment in my life.

You were dismissed by a note left on your car’s windscreen? Some have doubted that story…

Well, if it wasn’t true then I wouldn’t have left the band. I definitely got the note. It said: “Andy, you have left The Smiths – goodbye, good luck, Morrissey.” I thought it was a royalty cheque at first. It was on the windscreen of my car and I thought, “Ah great,” because it was in Morrissey’s hand-writing. Little did I know.

How did you get involved in heroin, it’s not very Smiths?

It was because of my surroundings. I lived on the edge of a pretty heavy council estate in Ashton Upon Mersey called the Race-course Estate. All my friends were doing it, I had three brothers, they were all doing it, you get a bit of money, what are you going to do? It just happened to be where I lived at the time and it was a habit that stuck.

So you were using before the band started?

I was, but because I didn’t have any money at that time I was just playing around with it. All of a sudden, you’ve got a lot of your money in your pocket, you give way to temptation.

Shortly after the sacking, you got busted. Did that do you a favour?

I didn’t think so at the time, but it brought things to a head. The others rallied round, Johnny especially was a great help. I don’t think Morrissey knew how to deal with it, so he kept away and hoped it would get better. It all worked out in the end. It’s not a big deal when it happens in bands now, but I suppose The Smiths were the last band you’d expect that to happen to.

Did The Smiths have a drug culture? How easy was it to go straight?

That’s a difficult one. To the outside world we were very clean, inside we all liked to experiment, shall we say. I just happened to get caught. To be honest, though, the easiest way for me to give up was to go on the road. The biggest lie in rock music is that everywhere you go there’s people offering you drugs. I can honestly say in five years in The Smiths nobody ever offered me drugs on the road, so that was my medicine.

A year later it was Marr’s turn to leave The Smiths, this time for good…

I knew he wasn’t coping. He had too much on his shoulders and it was putting stress on his marriage, so he had to make a choice between his family life or his professional life. I don’t blame him, he took the family route because that’s most important. It was a big body blow to everybody, him included. That decision must have been a massive stress. It’s a lot to carry on your shoulders, isn’t it? “I broke up The Smiths.”

Do you think if you had taken a break after Strangeways, Here We Come that might have kept you together?

I’d put money on it. If we’d have all took a month out, gone on holiday and emptied our heads of all the shit, I’m not saying we’d still be going now, but things would have lasted a lot longer and wouldn’t have turned out the way they did, so horrible.

The post-Smiths era has been bad…

It’s awful. It’s like a nightmare. None of us are able to speak to each other. I personally don’t feel like I’ve been the cause of any of it.

Yet you didn’t sue, like Joyce?

I was made to settle, basically. When we split up, all the assets were frozen, so I didn’t get paid for two years. I was on my arse, about to lose my house and I could either get paid and agree to this 10 per cent shit or go the same route as Mike. It’s taken him 10 years, by which point I’d have lost my house and would be selling The Big Issue, so I didn’t really have a choice.

What did you think of Morrissey’s “Bruce and Rick” insults aimed at you and Joyce?

Morrissey is a very humorous person, he can be very witty and very cutting. I was offended for a minute and then a minute later I was laughing at it, because I thought it was hilarious that he used that analogy. Good choice of words, Mozzer!

Tell us a nice story about Morrissey?

He did once visit my house when I was married and he brought my then wife a massive bunch of flowers, which I thought was really nice. I think they were lilies. That was a nice touch.

Copyright: Paul Stokes, reprinted with kind permission.