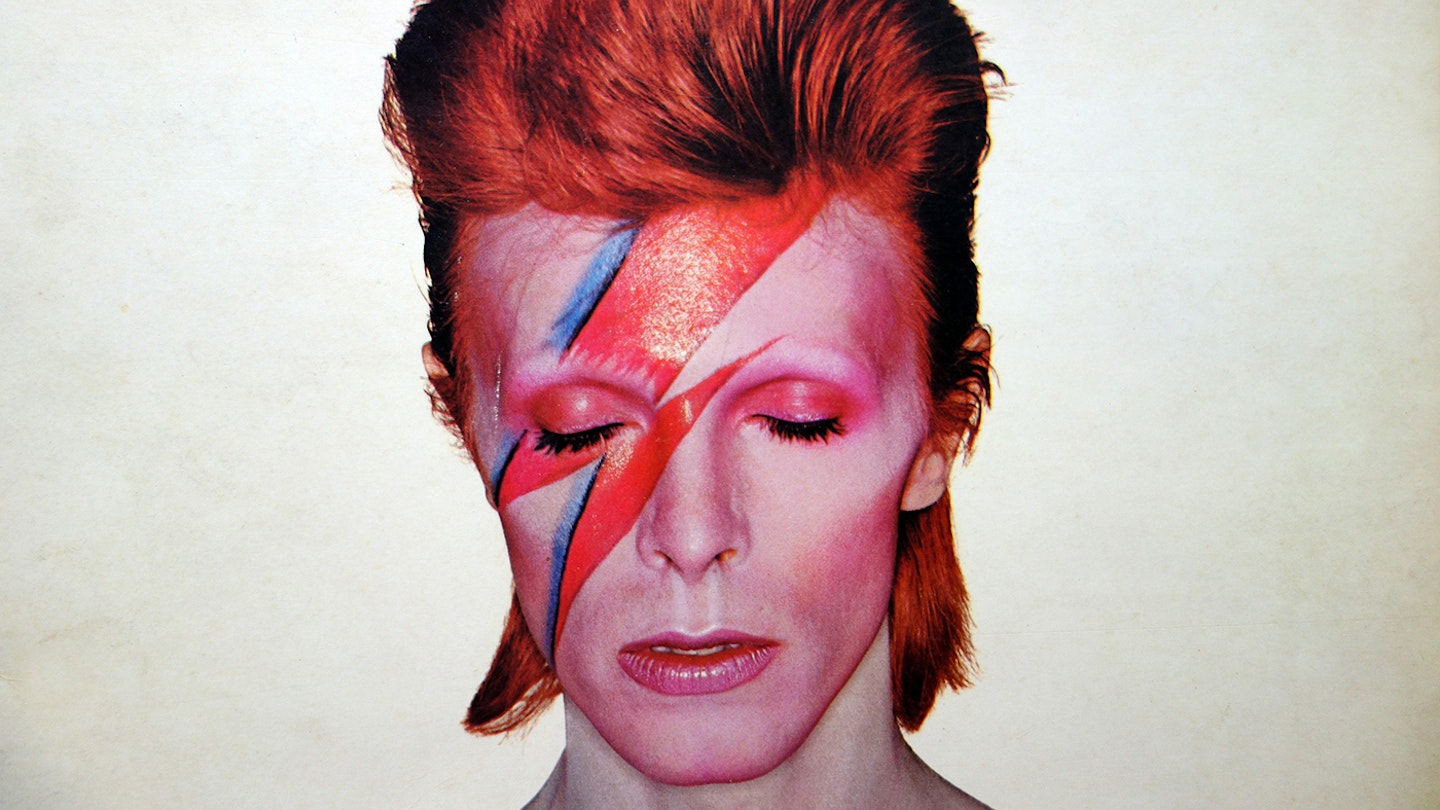

It can’t be common for an album artwork brief to begin with a demand for the most expensive treatment available. But these were David Bowie’s manager Tony Defries’s exact instructions to Aladdin Sane cover photographer Brian ‘Duffy’ Duffy.

“The key was to make something that was different and astonishing and important,” Defries tells MOJO today of the genesis for the iconic sleeve for David Bowie’s sixth LP. “Which we managed to do with Hunky Dory and Ziggy. But this needed to, in a sense, go up a step.”

Defries’s logic, explains Duffy’s son Chris – the man behind a new book containing the full story and shoot – was cunning. “He wanted to commit RCA, to make them spend as much as possible on Bowie, on the basis that they couldn’t then drop him. There was too much to write off.”

Duffy brought the luxe production values he’d already applied to the 1973 Pirelli calendar, where he’d collaborated with airbrush artist Philip Castle.

“For the reproduction, Duffy opted for this Kodak process called dye transfer, which produced a fantastic depth of colour,” the photographer’s son continues. “It also gave the right kind of surface for airbrushing. Then he had the plates made up in Switzerland. These were all the most expensive options you could choose.”

Bowie’s end of the brief was simple – he wanted a flash: something like the Taking Care Of Business logo used by Elvis since his return to gigging in 1969. And the record was to be called A Lad Insane (Chris Duffy claims the re-spelling was his father’s idea).

Preparing for the January 13 shoot at Duffy’s studio in London’s Primrose Hill, make-up artist Pierre Laroche started drawing a small flash on Bowie’s cheek. Duffy stopped him and sketched another across half of Bowie’s face: “Now fill that in.”

Chris Duffy has had 50 years to ponder its power.

“A flash by its nature makes you jump – so it’s got the drama,” he says. “The image is androgynous – it works for men and women – and it kind of poses more questions than answers. It left a lot for conjecture and speculation.”

One of the most fertile sources of speculation is the blob of reflective liquid that collects in the hollow of Bowie’s collarbone. Inspired by John Pasche’s ‘lips’ logo for The Rolling Stones, Duffy saw it as a merchandising opportunity. “He had a half a mind that the droplet could be a piece of jewellery,” says Chris Duffy. “That didn’t go anywhere in the end.”

-

READ MORE: David Bowie's 100 Greatest Songs Ranked!

For nearly 40 years after the April ’73 release of the album, Aladdin Sane’s eyes-closed image was pretty much the only frame from the shoot the public would see. Then, in 2010, Bowie approved the use of the colour, eyes-open alternate for the cover of Kevin Cann’s book, Any Day Now – the same shot subsequently employed by the V&A to publicise their blockbuster 2013 exhibition, David Bowie Is… Then, in mid-2020, the Duffy archive authorised the use of another outtake for the cover of MOJO. At last, Duffy’s new book delivers the shoot in its entirety, along with essays by Kevin Cann, Paul Morley, Charles Shaar Murray and others. The images also play a part in an Aladdin Sane: 50 Years exhibition at London’s South Bank Centre in April-May and a wider-ranging show, covering all five of Duffy’s Bowie shoots, debuting in Madrid this month. “I thought it was time fans saw all of it,” says Chris Duffy.

Bowie’s Aladdin Sane cover brought the values of ad-land to a cultural product, and delivered everything its clients had hoped for. RCA had paid through the nose, but weren’t complaining.

“Defries had a master plan to make David a world superstar,” says Chris Duffy. “But it’s funny: Bowie only ever had the flash on his face once, that one day.”

In Duffy’s book, Geoffrey Marsh describes the Aladdin Sane flash as exemplifying “all of David’s remarkable artistry but also the impact his career had on social values, freedom of expression and the potential for everybody to choose who they want to be.” Chris Duffy puts it more succinctly: “It’s the Mona Lisa of pop.”

Aladdin Sane: 50 Years by Chris Duffy is out now via Welbeck, £40. Aladdin Sane: 50 Years is also an exhibition at London’s South Bank, April 6-May 28. Bowie Taken By Duffy is now showing at COAM, Madrid.