A Complete Unknown

★★★★

Dir. James Mangold

In A Complete Unknown, James Mangold’s surprisingly sharp film about Bob Dylan’s ascent to fame, music is a weapon. Woody Guthrie (Scoot McNairy), whom Dylan (Timothée Chalamet) seeks out as soon as he arrives in New York in January 1961, famously slapped “This Machine Kills Fascists” on his guitar, but there are other means for a song to draw blood. Take the way Joan Baez (Monica Barbaro) falls for Dylan when she sees him perform the homicidal disgust of Masters of War in the heat of the Cuban Missile Crisis, or how the two of them tussle on stage in April 1965 over the opening chords of Blowin’ in the Wind — a symbol of what he no longer wants to be. Every performance is a flag in the ground or a shot to the heart. In fact, the whole movie feels like a bomb waiting to go off. The fuse is lit when Dylan first meets Pete Seeger (Edward Norton) at Woody’s bedside, timed to detonate four-and-a-half years later at the Newport Folk Festival.

Mangold and Scorsese collaborator Jay Cocks have wisely stuck to the narrative arc of Elijah Wald’s 2015 book Dylan Goes Electric! The director’s 2005 Johnny Cash movie Walk The Line was a sturdily conventional biopic: rise, fall, resurrection. But for Dylan the period covered here was all rise. It was the folk scene, as Seeger imagined it, that fell. Arguably this is not really a Dylan biopic at all. Citing Robert Altman’s busy ensemble dramas, the director is telling the story of a milieu rather than an individual.

Our hero (or anti-hero) materialises out of nowhere, with his Huck Finn cap and tall tales about working in the carnival, as mysterious to the viewer as he was to the denizens of Greenwich Village — the clue’s in the title. A Complete Unknown would make a great double bill with the Coen brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis, which ends pretty much where this begins, with Dylan sweeping into town like a coming storm: the 19-year-old It Boy who inspires wary fascination whenever he opens his mouth. “He was electric,” recalls folk musician Jim Kweskin in Wald’s book. “You couldn’t take your eyes off him.”

As Dylan, Chalamet’s eyes are shrewd and hooded, constantly working the angles and searching for the exits.

While most biopics are an attempt to understand and explain immense talent, this one is more about how it feels to be in the vicinity of a talent that defies such attempts. So instead of trying to unravel Dylan’s motivations (a fool’s errand), Mangold shows us him through the eyes of his contemporaries: Baez’s cool, regal scepticism, Seeger’s twinkly pride, manager Albert Grossman’s (Dan Fogler) flashing dollar signs. As Seeger’s wife Toshi, Eriko Hatsune barely speaks a word, but her face suggests that she’s the only person who can clearly track the shifting dynamics.

Being watched like that can mess with a man’s head. As Dylan, Chalamet’s eyes are shrewd and hooded, constantly working the angles and searching for the exits. He’s the smartest person in any room, and he knows it. When he tartly compares Baez’s lyrics to “an oil painting at the dentist’s office,” she snaps back, “You’re kind of an asshole, Bob.” He doesn’t reject the diagnosis, and nor does the film. As in the Dune movies, Chalamet plays the chosen one with an underrated capacity for destruction. At times he has the air of a dangerous child, easier to love than to like.

On a date with Sylvie Russo (Elle Fanning), Dylan sees Now, Voyager and says of Bette Davis’ character, “She didn’t find herself. She just made herself into something different.” Sly and wiry, Chalamet is playing a man whose whole life in New York was an evolving performance. As the clothes darken and the sunglasses come on, he grows increasingly mannered and alone, trapped by his own pathological contrarianism and dedication to inscrutability. He is often seen in long shot, standing apart from his supposed peers.

Beyond the tremendous core trio of Chalamet, Norton and Barbaro, all of whom learned to sing and play their songs remarkably well, lies an outer ring of vibrant performances. Will Harrison is a suitably Mephistophelean Bobby Neuwirth and Boyd Holbrook superb as Johnny Cash, the blazingly charismatic cheerleader and shit-stirrer. Norbert Leo Butz’s portrayal of Alan Lomax as a bullnecked reactionary may be somewhat unfair on Lomax but does give us some hilarious lines. “It’s the Newport Folk Festival,” he roars. “Not the Teen Dream, Brill Building, Top 40, British Invasion Festival!” This machine kills purists.

Mangold and Cocks tailor the facts to tell a very specific story. Fans might grumble about omissions, like the March on Washington (only glimpsed on TV) or Dylan’s UK adventures, but the movie’s world is a closed loop of New York and Newport and cameos of Martin Luther King or The Beatles would not have improved it. It’s not particularly interested in the politics of the time, but then nor, despite initial pretences, was Dylan. Setlists and recording dates are tweaked to tighten the narrative and sharpen the themes. “People make up their past,” says Dylan, as if to forestall viewer complaints. “They remember what they want to and forget the rest.”

Reportedly, the real Dylan introduced some of his own inaccuracies when he gave Mangold notes on the screenplay. He was the one who requested that his ex-girlfriend Suze Rotolo be replaced by the fictional Sylvie Russo, who gets to stay in the picture all the way to 1965, an increasingly exasperated ambassador from the realm of the normal. In a biopic that rations its cliches, only the decision to relocate the infamous cry of “Judas!” from Manchester ’66 to Newport ’65 feels like an intruder from a cheaper, sloppier movie.

The most significant fabrications involve Dylan’s relationship with Seeger. In reality, the two men didn’t meet in Guthrie’s hospital room but months later, when Seeger had already heard the buzz about the newcomer. One of the film’s juiciest scenes, when Dylan gatecrashes Seeger’s TV show Rainbow Quest, is also complete fiction. Seeger is made out to be Dylan’s patron from day one so as to set up the patricidal drama of the journey from Song to Woody to Like a Rolling Stone.

Some critics have referenced Mozart and Salieri in Amadeus but that doesn’t feel right. Seeger doesn’t envy Dylan’s uncanny talent, he just wants him to use it in the service of peace, justice and folk music. When Dylan plays The Times They Are a-Changin’ at Newport ’64 (another deft invention), Seeger listens delightedly to the line “Your sons and your daughters are beyond your command,” without realising that Dylan means him, too. “You’re pushing candles,” Grossman tells Seeger later, “and he’s selling lightbulbs.”

With his cosy knitwear and a folksy manner that’s a mere banjo string away from that of a children’s TV presenter, Seeger could have been a figure of fun, but Norton and Mangold take him seriously as an idealistic champion of communal endeavour and the golden thread of tradition. He’s the gentle warrior who tended the folk scene’s flame throughout the winter of McCarthyism and heralded the spring. Dylan publicly called the older man “so human I could cry”. So when their relationship curdles into that of an embarrassing dad and an eye-rolling teenager (Cash is the hip, indulgent stepdad), the film refuses to take sides.

This even-handedness is sustained through to the final showdown at Newport ’65. As Wald’s book illustrates, there’s no consensus on how that chaotic, seismic three-song set was received by the 17,000 spectators, so Mangold stages it as a mythic spectacle, midway between the premiere of The Rite of Spring, a 1985 Jesus And Mary Chain gig and the Battle of Gettysburg, with Seeger and Dylan’s more belligerent proxies, Lomax and Grossman, actually coming to blows. The real Lomax complained that Dylan “more or less killed the festival”. It’s not the amplification that causes uproar, it’s the attitude. Here is the final victory of I over we; individual liberty over the greater good; the singer over the song. “Freedom from us and all our shit,” says Baez. “Isn’t that what you wanted?”

-

READ MORE: Bob Dylan’s Greatest Songs, as chosen by Paul McCartney, Patti Smith, Nick Cave and more…

But what does that freedom cost him? When Dylan is coaxed back onstage to perform a solo acoustic song and he chooses It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue, you realise that what you’ve been watching all along is a break-up movie. Afterwards, we see him brooding alone in his motel room — no longer unknown but forever unknowable. Triumphant he is not. I was reminded of producer Joe Boyd’s ambivalent account of Newport: “The rebels were like children who had been looking for something to break and realised, as they looked at the pieces, what a beautiful thing it had been.”

Of course, we know how this played out — the book isn’t called Does Dylan Go Electric? — but we’re still riveted because Mangold puts us in the shoes of those who had no idea. He invites us to listen like them, too, so that these 60-year-old songs sound like the future, crackling and volatile. This urgent freshness is the movie’s greatest achievement. As Sylvie says of folk music, every old song was new once.

A Complete Unknown is in UK cinemas from January 17.

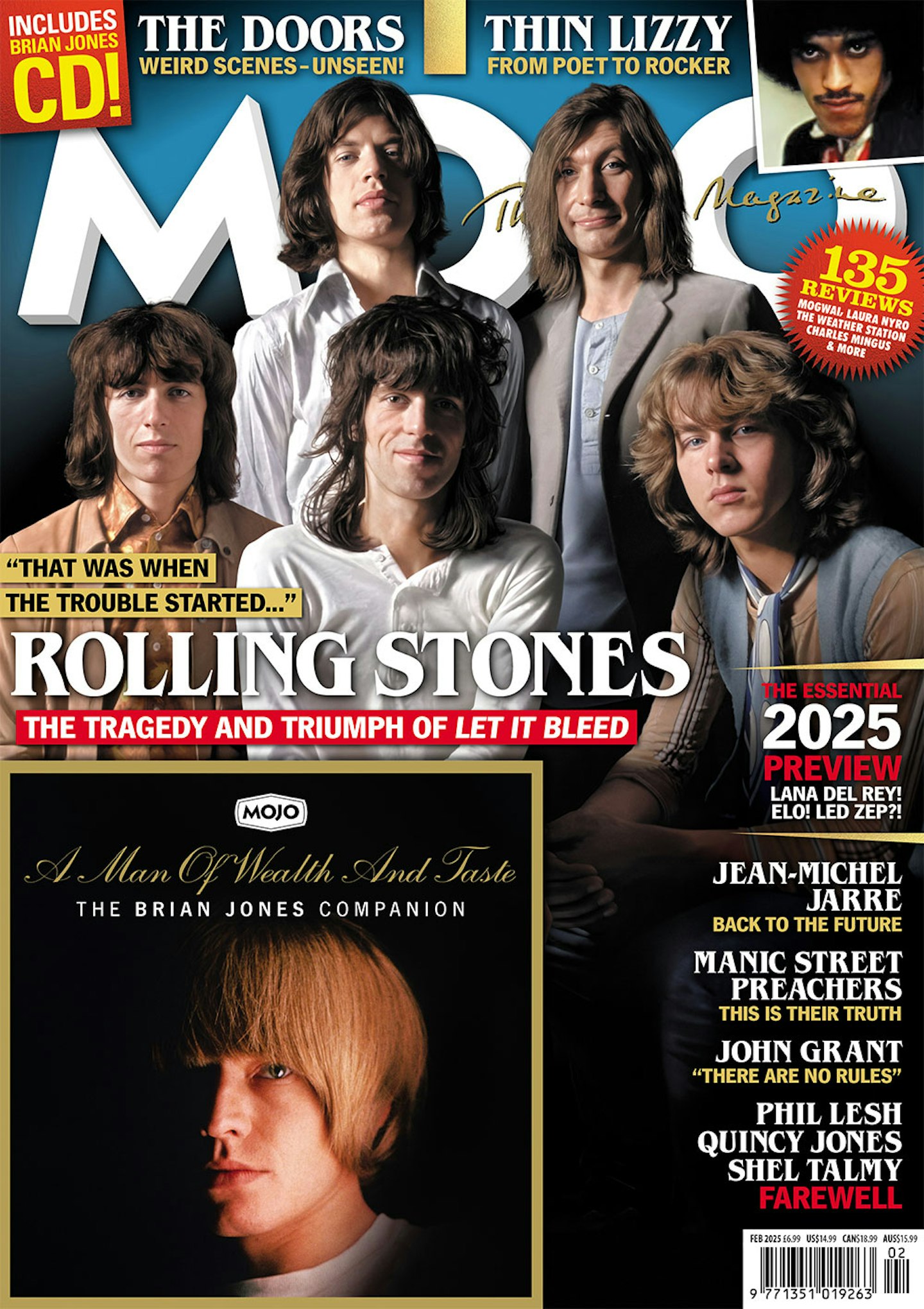

Get the latest issue of MOJO for the definitive verdict on the month's best new music, reissues, music books and films. More info and to order a copy HERE!