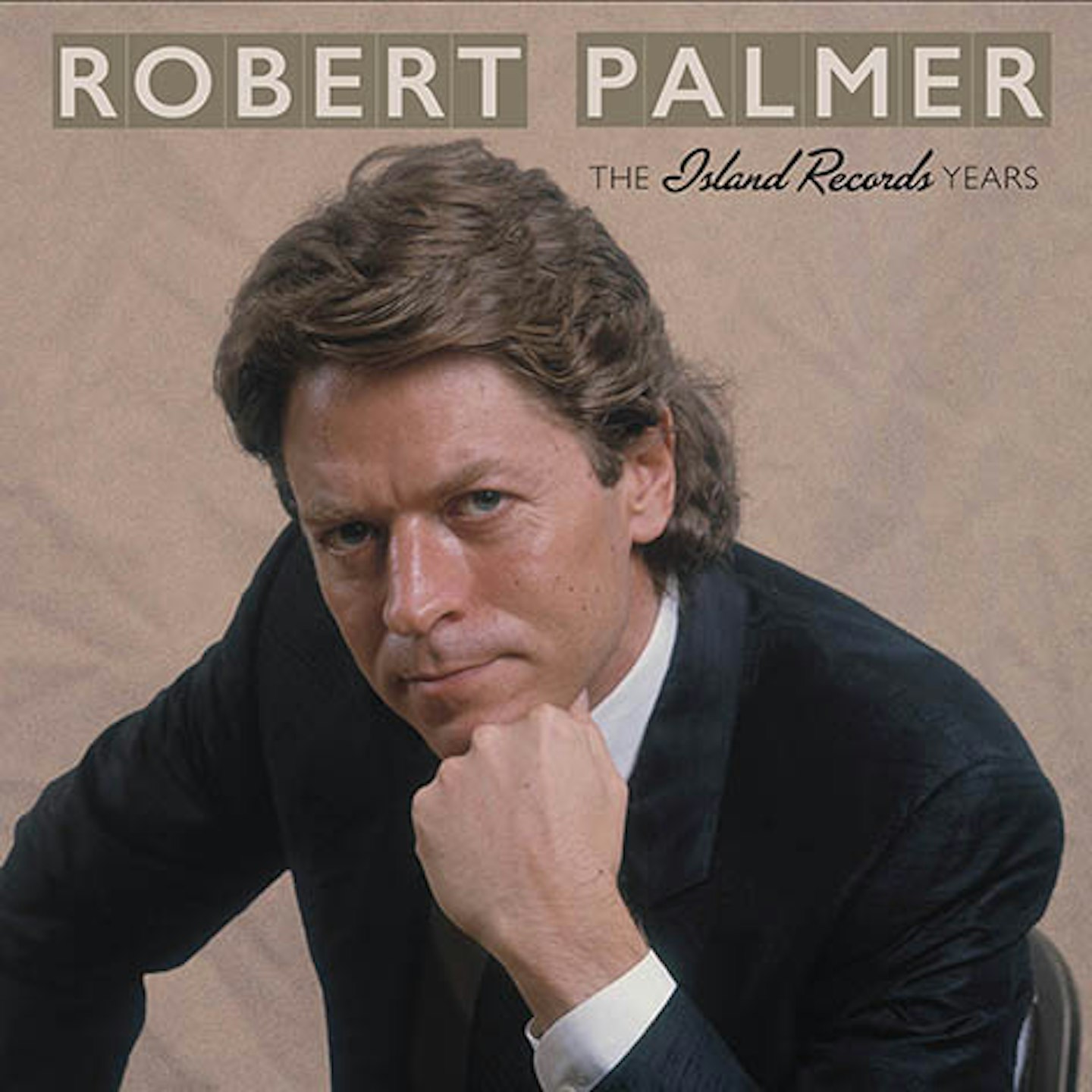

One of the finest pop creators his in plain sight behind the image of a singing gentlemen of leisure. But beneath the expensive tailoring lay a fiercely dedicated, eternally curious musical lifer.

Robert Palmer

★★★★

The Island Years 1974-1985

EDSEL/DEMON. CD/DL

In the summer of 1983, I worked in a record shop where one of our favourite things to blast on the stereo was a compilation cassette of lesser-known Robert Palmer tracks: from sexy early single Give Me An Inch – featuring an extraordinary bass performance by James Jamerson – the slinky You Overwhelm Me and woozy, Eastern-sounding Found You Now, to that year’s The Silver Gun, a strange, shape-shifting song sung entirely in Urdu. Every time we played this tape, customers would drift to the counter to ask what it was. When told it was Robert Palmer, they’d most likely say, “Who?”, or perhaps occasionally, “What?!” Whatever their foreknowledge of him they had no idea he sounded like this – and we could usually sell them an album.

It’s not surprising that someone’s personal distillation of his work showed it off well, as mixtapes were Palmer’s preferred medium for enjoying music. He’d stuff them with everything from Fred Astaire to African folk, and his albums ran a similar course. 1983’s Pride (his eighth), took in electro-calypso, reggae, proto-techno, disco pop and a yearning, eerie ballad, Want You More, regularly punctuated by the sound of someone diving into a swimming pool. It followed another fine album, Clues, that covered Gary Numan, sequencer-driven funk, the superb Johnny & Mary, boogie metal and powerpop. Previous records had expertly handled New Orleans funk and Philly soul and featured The Meters and Little Feat among the players. They’d won Palmer a large cult following that understood his thirst for all musics. Critics at the time, however, mistrusted him, crying ‘dilettante’ and ‘inauthentic’, while praising fellow changelings like Bowie and Ferry to the skies. Palmer could be their equal as a songwriter (Johnny & Mary? Come on! Ferry himself has covered it) but never received a tenth of their attention.

Essentially, he was a fan. Chris Blackwell ranked Palmer the most knowledgeable music nut he’d ever encountered.

However, three years after my record shop stint, everyone knew Robert Palmer. In early 1986, he’d just come out of supergroup The Power Station with members of Chic and Duran Duran, when he and Island founder Chris Blackwell sat down together to watch photographer Terence Donovan’s video for Addicted To Love, the third single from his ninth Island album Riptide. In his autobiography, Blackwell states Palmer wasn’t on set when the models shot their sequence, so didn’t know what they’d done until he saw the finished cut. (If that’s true, the combining of the two shots was ingeniously done for its time.) He was as riveted as anyone else by what Blackwell calls the models’ “glorious indifference”. The male gaze is Donovan’s; Palmer behaves like it’s another day at the office. When a TV interviewer called the video sexist, Palmer replied in a broad Yorkshire accent, “There’s nowt wrong wit’ being sexy.” On the surface it came across as dense and oblivious, but he knew perfectly well what he was doing. His noncommittal stance wound people up, as did his refusal to stay in one lane. He didn’t seem to care what people thought, but he didn’t want to be categorised.

In 1978, around the excellent Double Fun (a co-production with Tom Moulton), Palmer described himself as a “presenter of music”. “I can write songs, arrange music, produce records and take a show on the road. It is a more abstract venture; it’s not just being a singer.” Fundamentally, he was a fan. Blackwell ranked Palmer as the most knowledgeable music nut he’d ever encountered, acquiring a taste for obscure sub-genres and new trends long before anyone else. Raised partly in Scarborough, partly in Malta (his dad was in naval intelligence), he was exposed very early on to the curious mix of sounds that floated over that island: soul and rock from American Forces Network, Italian pop, African highlife and calypso. He also became obsessed with the smart Italian naval uniforms he witnessed, striving to make his school uniform look just as sharp.

That all instilled a deep-seated understanding of style that stayed with him. It was what Blackwell first spotted, in the crowd at a smoky club on the outskirts of London in 1970, waiting for The Alan Bown! to perform. The band’s singer was late. Enter a glamorous couple who stood out among the Afghan coats and dungarees, looking like they’d arrived from St Tropez. It was Palmer and his wife Shelly. And he was the singer they’d been waiting for. When he stepped on-stage and employed a husky, nicotine-steeped tone, Blackwell knew he’d found something special. He subsequently signed him to Island as part of Vinegar Joe – a promising rock’n’soul troupe that never quite gelled – but was convinced he’d fare better as a solo artist, encouraging him by offering him a condominium in Nassau, where Island subsequently opened a studio complex, Compass Point, in 1978. This gave Palmer instant access to a workspace while keeping him away from distractions (he loved to party), enabling him to focus on his eclectic instinct.

The carnival of styles that passes before you on the mercurial records he made for Island, all nine of which are deftly remastered and annotated here, can be off-putting. Some of his enthusiasms haven’t aged well. Sculpting your own route through his work is advised. But as you do, you’ll notice that Palmer’s ability to tease out the inspirational threads connecting his wide-ranging choice of covers – Kinks, Kool & The Gang, Allen Toussaint, Todd Rundgren – was uniquely playful and smart, and his own writing frequently surprising (Addicted To Love’s lyric doesn’t fit its melody, requiring some stunt scansion) and ran deeper than you’d think (“Mary counts the walls” – such a great line).

A full-throttle lifestyle – 60 cigarettes a day, martinis for breakfast, and a rumoured affair with Princess Diana (possibly the inspiration for Simply Irresistible) – caught up with him at the age of only 54 in 2003. Too soon. Reassessment of his legacy is long overdue. Let’s hope this handsome box helps. OK, Addicted To Love is still an elephant in the room, but the rest of the menagerie he created – Pterodactyls! Dolphins! Unicorns! – is well worth a visit.

The Island Years 1974-1985 is out now via EDSEL/Demon.

READ MOJO'S VERDICT ON ALL THE MONTH'S BEST MUSIC. Plus, receive every new issue of MOJO on your smart phone or tablet to listen to or read. Enjoy access to an archive of previous issues, exclusive MOJO Filter emails with the key tracks you need to hear each week, plus a host of member-only rewards and discounts by BECOMING A MOJO MEMBER