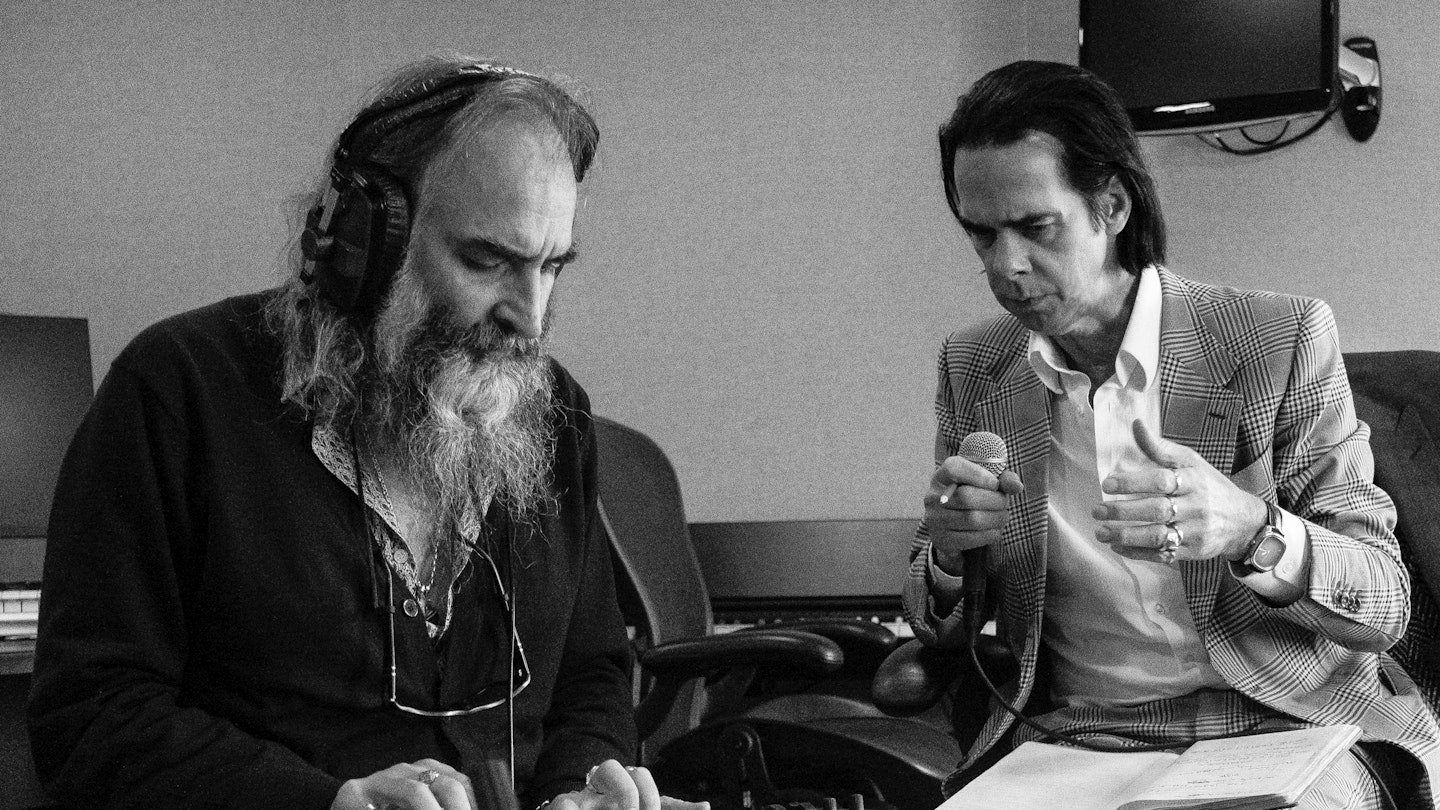

NICK CAVE IS NOT shy about the fellow feeling he shares with Warren Ellis. When the multi-instrumental Ellis first played with The Bad Seeds in the early ’90s, he was just starting life alongside The Dirty Three. Cave spotted in Ellis a ceaseless swirl of ideas and inspirations, leading to Ellis’s near quarter-century as a Bad Seed, a string of scores together, and an enduring bond with the famously fractious songwriter. “There is a certain sanctity in this friendship in that it has traversed all manner of troubles,” Cave wrote in his Red Hand Files in 2018. “When one of us is in trouble, the other comes a-running.”

Has this year of quarantine, social upheaval, and prevailing unease been anything if not trouble? Cave and Ellis ran toward each other, it seems, ruminating on the headlines, and writing and recording their first studio album as a pair while in the throes of lockdown. The eight-song result, Carnage (Goliath Records LTD), is a jarring and gorgeous reminder that our suffering is neither new nor negligible, or, as Cave growls during the gothic paroxysm Old Time, that “history has dragged us down to our knees.” Yet, no matter how tired we are of cancelled plans or the humdrum view from our window, we keep reaching for the sanctity of friendship, for the promise of anything better than now.

Despite the limited line-up, the palette of Carnage feels familiar from 2019’s harrowing Ghosteen – throbbing electronics, abrasive strings, warped voices, occasional lullabies. The title track is a world-weary tone poem, its minimalist lurch repeating “like a raincloud that keeps circling overhead.” With its woozy synthesizers, somnolent strings, and tired croon, the balladic Albuquerque laments our homebound existence, looking for escape and romance in our dreams.

But the true power of Carnage comes when the pair puncture those clouds. Cave enters demented Pentecostal mode for Scattered Ground, his anguished voice trying to will him into being whole. In the back half of the seething White Elephant, Cave and a gospel choir reach for redemption: “We’re all coming home/For a while,” they assure us, jubilant with the word.

More than clashing sonics or soaring hymns or pervasive anxiety (and the quest to overcome it), the quality that best defines Carnage might be Cave’s reckoning with the unknown, or his recognition of the unknowable. “There are some people trying to find out who/There are some people trying to find out why,” he mutters, over Ellis’s inquisitive drone. “What am I to believe?” he sighs, to start the finale.

Indeed, what should you make of the fallen statue uttering the last words of George Floyd in White Elephant only to be kicked into the sea, or the violent “Botticelli Venus with a penis” one verse later? And to what do you cling when everyone has vanished, perhaps including you, as in Lavender Fields? In their case, at least, you run to each other, in hopes of making any sense of any of this.