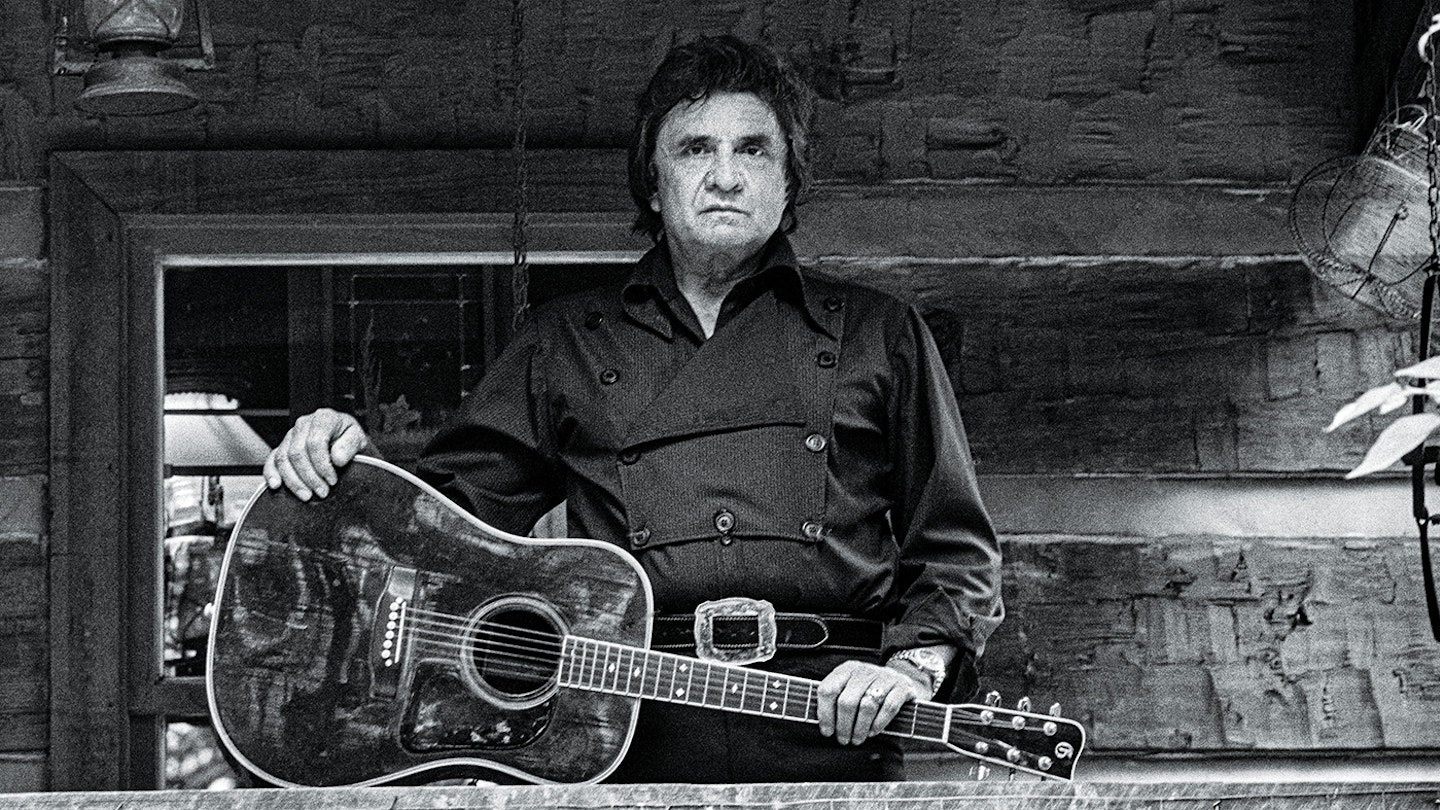

Johnny Cash

Songwriter

MERCURY NASHVILLE/UMC

★★★★

IN early May, the crooning country star Randy Travis released Where That Came From, a glowing but sombre shuffle about a magic love he’d lost. It was a ringer for the deftly melodramatic tunes that made Travis, with his curiously curling Southern twang, one of the form’s key figures beginning in the mid-’80s. Diggin’ Up Bones, Forever And Ever, Amen, On The Other Hand: the new tune represented a renaissance for Travis, hingeing on the same deft lyrical play and idiosyncratic tone as those songs that made him famous. For the past decade, though, Travis has struggled to speak, let alone sing, after almost being killed following a string of infections and a massive stroke. Where That Came From, then, came from AI, which had absorbed the successes of his seemingly lost past to stake a potential future.

-

READ MORE: "Dad was working hard, giving everything he had..." John Carter Cash on the story behind Songwriter.

Expect much more of this from country music in years to come. Despite the continually widening scope of its sound and its sporadic steps toward inclusion, country has forever been defined by a kind of antediluvian idealism, a get-back-to-the-homestead nostalgia for the way things were. And so it goes now with an unwavering devotion to its bygone forebears. Hank Williams or Johnny Cash, Loretta Lynn or Waylon Jennings, Charley Pride or George Jones: these are figures to be worshipped, not waylaid. And if there is a way for technology to revive the corpse’s voice, wager most estates will use it, especially as many of the genre’s marquee icons near what must be their final years.

In that context, it is tempting to dismiss Songwriter – the new album from Johnny Cash, who died two decades ago in Nashville at age 71 – as, at best, some desperate attempt to keep him around and, at worst, a cynical cash-in. In the early ’90s, Cash, like many of his fellow elders, was too old to be considered cool but too young to be unapologetically feted with the laurels of legacy. The ’80s had been rough-and-tumble for Cash: while daughter Rosanne flirted with spiky crossover success, her father faltered both during repeated rehab stints and a mangled relationship with Mercury Records. Amid that doldrum, in 1993, he cut some demos of new songs at LSI Studios, then being run by his stepdaughter and son-in-law. Fellow iconoclast Waylon Jennings added occasional harmonies, but the sessions were otherwise simple – Cash’s guitar and that singularly stentorian voice, a touch of tenderness slipping into his tone near the end of middle age.

The last decade of Cash’s life is now lore: a year later, he partnered with Rick Rubin, cut multiple volumes of their stark American series, and rightly found his perch as an elder statesman not only of country but of international redemption. In that hubbub, those demos remained forgotten until John Carter Cash, the only kid of both Johnny and June, found them and wondered what best to do with this final trove of songs. Could they affirm his father’s status as more than a mighty cover artist during his final years? He dumped the sessions into software, peeled off his father’s voice, and assembled a motley bunch of aces – Marty Stuart, Vince Gill, Dan Auerbach, Dave Roe, Pete Abbott – to stitch full arrangements around them, to sweep the voice of Cash and his tunes back from a dustbin of demos, using technology’s burgeoning time-hopping power.

Opener Hello Out There presents instant cause for pause, its pulsing bells, gothic background vocals, and exaggerated strings attempting to put Cash in conversation with a future he never knew – namely the postmodern outlaw updates of Sturgill Simpson. It is, after all, Cash’s sociopolitical and vaguely surreal prayer for divine relief, prime Simpson terrain. It brims with early-’90s references to the Pale Blue Dot and net worth. However intriguing it may be, its rendering here suggests dropping off a longtime hermit in the rush of midtown Manhattan and telling him to figure it out. Cash would have had little context for this, so he sounds like a stranger masquerading in a strange land.

But the crew smartly curbs its revisionist impulses for the subsequent 10 tracks. They let Cash lead arrangements that alternately suggest the rocket-fuel directness of The Tennessee Three, the kind of deep ensembles Rubin sometimes assembled for him, or a countrypolitan state of grace. Poor Valley Girl, a love letter to June and her First Family Of Country, is rippling and lean. Well Alright, a winking sketch of laundromat seduction, is as hot as Nashville blacktop come August. And Drive On, an empathetic anthem for peers that were scarred by the madness of Vietnam but limped their own way into the future, is buttressed by grumbling bass and wallpapered with wisps of noise, twin reminders of that era’s enduring social dissonance.

But it is, in the end, Cash’s songs that star here, imbued not only with his humble history but the lessons of what he’s witnessed on the roller-coaster from penury to celebrity to near-madness. During Spotlight, he wishes away the unrelenting glow of fame, hoping to shield himself from the ways it will expose him. A character study of a truck-driving single mother who finds the life-sustaining solace she so desperately needs in the soothing if tormented songs of James Taylor, She Sang Sweet Baby James doubles as an expression of empathy and a portrait of music’s highest power. And Have You Ever Been To Little Rock is a charming paean to his benighted homeland, to loving something others lampoon. “It’s the land of my family/Down in Cleveland County,” his voice booms, smile audible. “It’s where my mama and daddy were born/Where the singing pines grow.”

The power of Cash’s American series stemmed in part from its relatability – a treasured voice of the past making a mesmerising game of karaoke from songs you might love and be surprised to hear him sing. There was a recognition in the astonishment. But on Songwriter, there is a recognition in the ordinary, in the way a sexagenarian ostensibly at the nadir of his career looks back on his life to marvel at its bounty, from family and home to love and survival. These songs would not have sparked the miracle of Cash’s last act like those Rubin recordings, but they are reminders of the real person behind that astonishing finale, of the feelings he faced and wrote before he voiced them through the words of others. Songwriter is indeed a by-product of music rendered on a digital frontier; it is a worthy effort because it reinforces the humanity of a star who, in his last days, could seem like some untouchable god.

Songwriter is out on Mercury Nashville/UME.

PRE-ORDER: Amazon | Rough Trade | HMV

Tracklist:

1. Hello Out There

2. Spotlight

3. Drive On

4. I Love You Tonite

5. Have You Ever Been To Little Rock?

6. Well Alright

7. She Sang Sweet Baby James

8. Poor Valley Girl

9. Soldier Boy

10. Sing It Pretty Sue

11. Like A Soldier

Get the definitive verdict on all the month's best new albums, reissues, books and films only in the latest issue of MOJO. More information and to order a copy HERE!