Can

Live In Paris 1973

★★★★

SPOON

CAN DRUMMER Jaki Liebezeit left the planet in 2017, but in 2020 his pal and collaborator Jono Podmore compiled rhythmic biography The Life, Theory And Practice Of A Master Drummer. It’s a book packed with curiosities. These range from a decoding of Liebezeit’s esoteric ‘dot-dash’ percussion thesis to his instrument collection (he treasured his father’s old accordion), as well as the repertoire of facial expressions he favoured for photo shoots, with “visionary gaze into the distance” in pole position. It also details his thoughts on the problem of ego, arguing that, “it holds us tight, it dictates the illusion of the self… when you get rid of it, that is where it all begins.”

As this ongoing archival project re-states, Can seemed particularly able to renounce such psychic bonds when in the live arena. Drawn from the audio stash of late collector Andy Hall – who nobly made his earliest recordings with a tape recorder stuck down his trousers – previous volumes in the series presented long-for m, all-instrumental murmurations in Brighton and Stuttgart in 1975 and a shorter, punchier groove-based show from Cuxhaven a year later. All are indispensable for Can junkies, allowing those who never got to witness them in the flesh a chance to experience their in-the-moment creative spontaneity, with the type of sonic upgrade and judicious enhancement that hissy old bootleg recordings do not have.

READ MORE: Damo Suzuki remembered: “Life is so short, so face in front of you, not backside.”

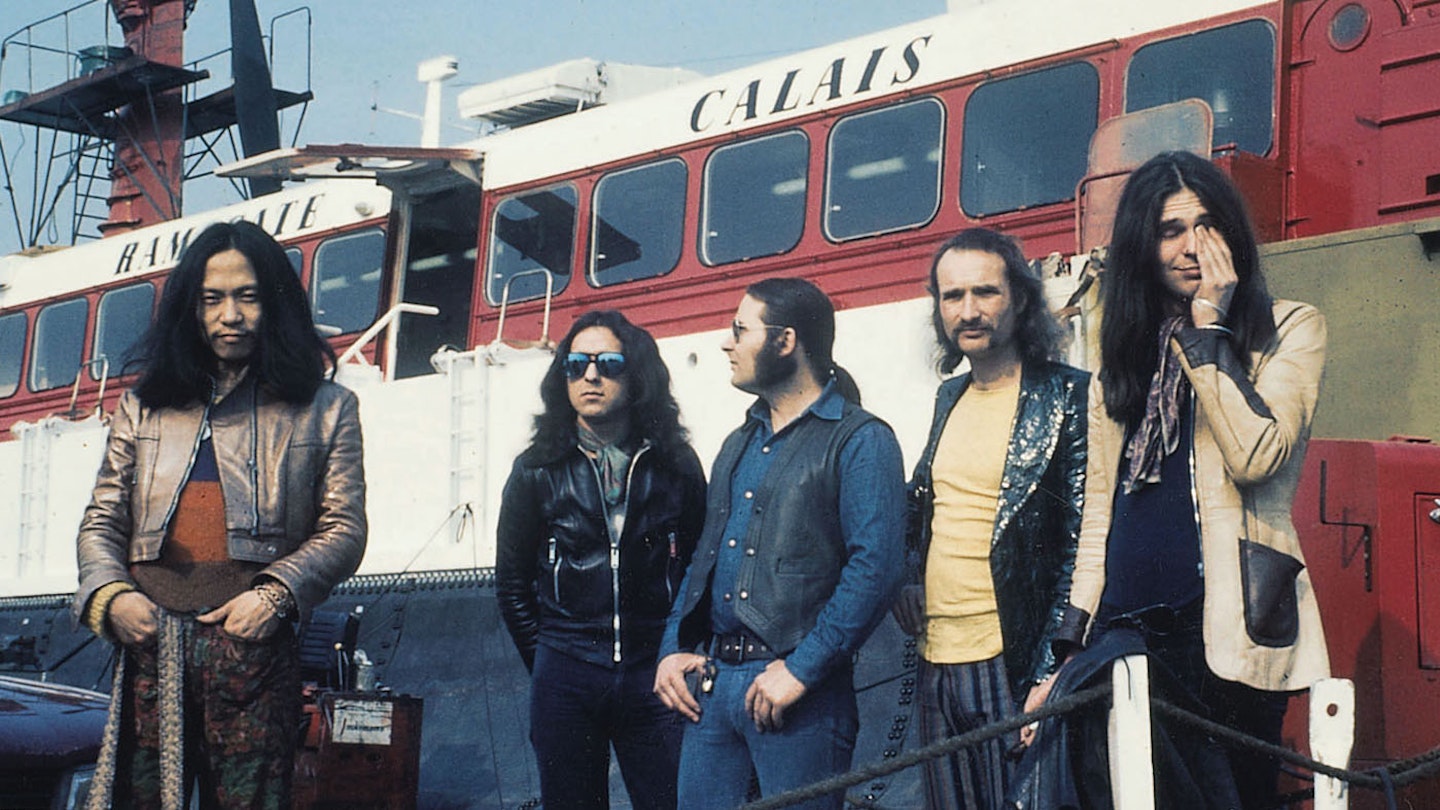

This latest volume, captured at L’Olympia in Paris on Saturday, May 12, 1973, is a longtime favourite among tape aficionados and also the most astonishing of the series so far. At the time, Can were firing creatively and commercially: febrile TV theme Spoon had been a massive hit in West Germany a year earlier, allowing them to move to their fabled studio and chamber of mysteries Inner Space, outside Cologne. The mesmeric funk totalities of Ege Bamyasi, a refinement and distillation of ground hinted at on 1971’s Tago Mago, soon followed. This was one of the great formations in Can’s history, with frontman Damo Suzuki a kind of meditative Tasmanian devil, who screamed and whispered in a rhythmic wordless argot he memorably called “the language of the Stone Age”.

It’s worth noting that Can’s studio modus had been to extemporise freely and lengthily and then to edit and structure the raw material into recognisable pieces. The other live albums found them imposing order, high-wire style, at the moment of creation. Though the five tracks presented here are given baldly numeric titles, with this performance we have the unfamiliar and bizarre situation of several of them being recognisable songs, played more or less as they were written – a special kind of heresy for a group who never played the same thing twice.

Of course, they ’re still striking out into the unknown, blindfolded. Opening piece Paris Eins 73, weighing in at a mere 36 minutes, hints at the oncoming storm with initial tremors. As guitarist Michael Karoli picks out gothic filigrees and bassist Holger Czukay plays one note repeatedly, Liebezeit is soon turning up the cold velocity: to Irmin Schmidt’s church organ drones and odd mid-air whirlpools conjured from his Alpha 77 synth, Suzuki engages in urgent conversation with himself and the music, clad, no doubt, in future-facing bellbottoms. Soon a baggy lope with Wagnerian fuzz guitars, the sweaty feverishness of Ege Bamyasi is palpable as the bass line and beats from Vitamin C and the discordant plink plonking of One More Night make fleeting appearances. No one seems to care what anyone else is doing, so how does it arrive at such order, as when it shifts into a near-bubble-gum boogie rock ascension? Is voice-percussionist Damo Suzuki singing, as it seems he is, “we’re spinning on the down when it’s lean in the steam?” Before you can ask, the head-nodding reaches its apex and comes to a leviathan, Germano-funk pause, with a clipped Liebezeit variation on the Amen Break and Michael Karoli in country twanging mood. “Well you hang out with a silly guy you chew the bow and your ears turn…” insists Suzuki, maybe: the crowd lose it after the everything-at-once climax as if it’s the last song.

For many groups, such a vitals-sapping performance would be, but back in ’73 we’re off into a kicking nine-minute version of Ege Bamyasi’s One More Night, where the whole group descend on one point in space and laser onto it, achieving zero gravity as Karoli seems to play the blues on an egg slicer and Schmidt plays helium organ. It falls apart like a jellyfish on land towards the end, becoming spectral as Czukay ’s bass flows. The manipulation of space and time continues with a clap-along version of Spoon previously enjoyed on 2011’s The Lost Tapes box set. They ’re working within structure but there’s still extemporising: after the song starts gathering grit and discord, everyone fixatedly accelerates, each element dovetailing into a repetitive, non-Euclidean one-ness to the point of near-nausea.

Anyone feeling queasy will have to hold on tight as howling, punishing track four pre-empts the helicopters, napalm and delirium of the opening sequence of ’Nam movie classic Apocalypse Now. If Damo Suzuki does sing in the language of the Stone Age, here is where Can raise their titanic menhirs and lay out their solar temple for the prehistoric spacemen to navigate by. Freak-out heavy it may be, but it still floats above the ground. It’s almost a relief to get to a relatively straight version of Vitamin C, though this too becomes a monster pummelling your brain and body before ending with insouciant abruptness.

Of course, it couldn’t last. Their next album was the ambient relaxant Future Days in August ’73: a month later Suzuki said he was leaving. Can existed in physical form for another six years, though as this time-portal demonstrates, their potency as a power force, ideal and totem endures and will endure. Another choice Jaki Liebezeit detail in The Life, Theory And Practice Of A Master Drummer was his idea of using soluble vitamin pills to induce foaming at the mouth during gigs, so everyone would think he was in a trance: if he did this during Live In Paris 1973, you’d have totally believed it.

SPOON. Out February 23

ALSO AT: Rough Trade

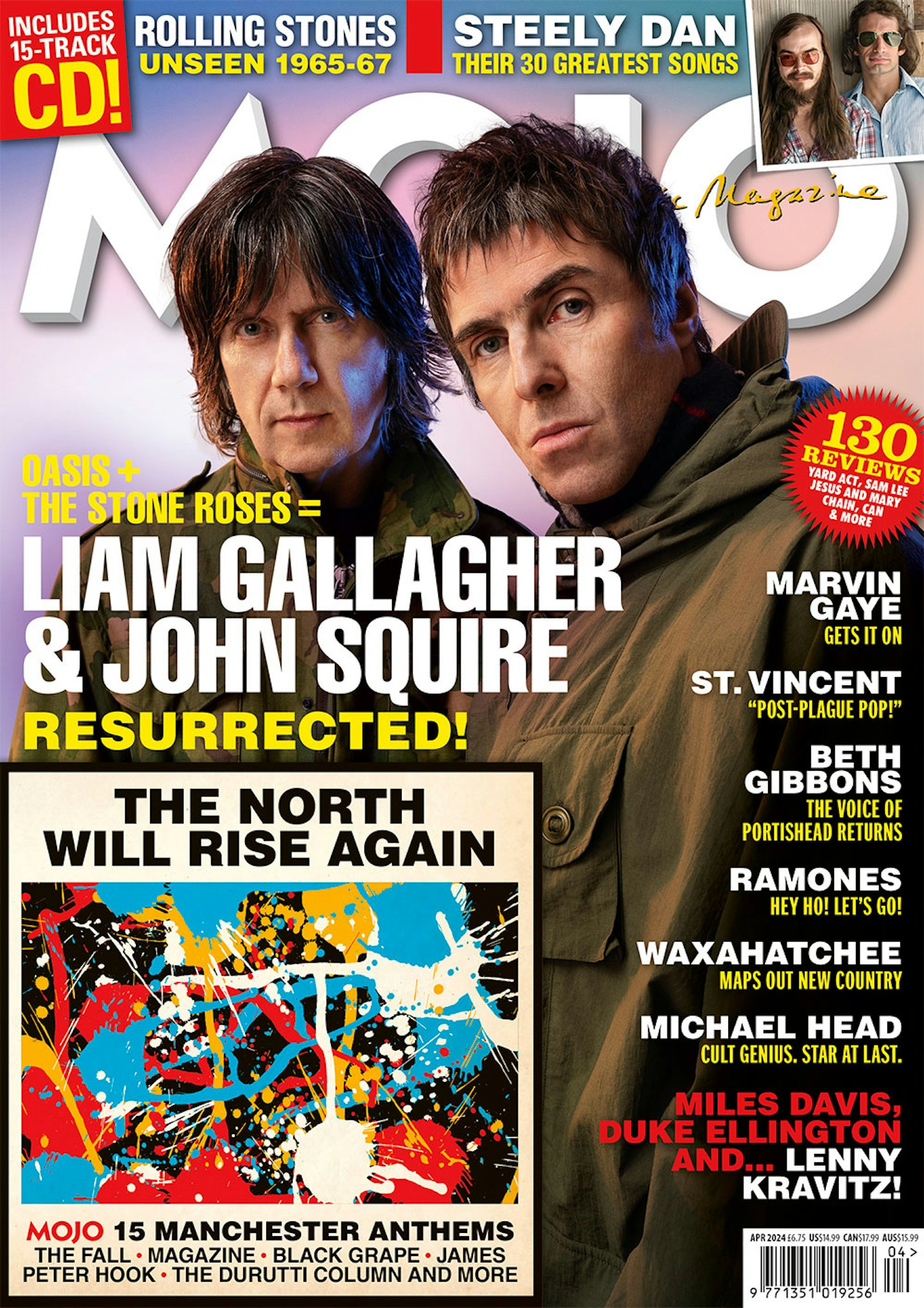

Read MOJO's verdict on all the month's best new albums, reissues, books and films in the latest issue of MOJO, onsale now. More information and to order a copy HERE!

Picture: Hildegard Schmidt